The COVID-19 pandemic wreaked havoc for the banking industry. With no respite in sight, banks will need to find ways to aggressively cut costs in the near term. But the current approach of closing branches and letting employees go has proved disruptive and painful.

A far better alternative is hiding in plain sight: optimizing procurement. For most banks, savings are waiting to be tapped across many categories, and a wide variety of levers are available to tap them. Optimizing procurement, in fact, is one of the least disruptive and fastest ways to achieve significant savings.

Procurement spending can account for up to 45% of a bank’s total cost base. In our experience, banks that take an aggressive approach to improving procurement typically save 10% to 15% annually on their total procurement spending. Savings of this magnitude can boost net income before taxes by 3% to 4%.

Extreme Measures in an Extreme Year

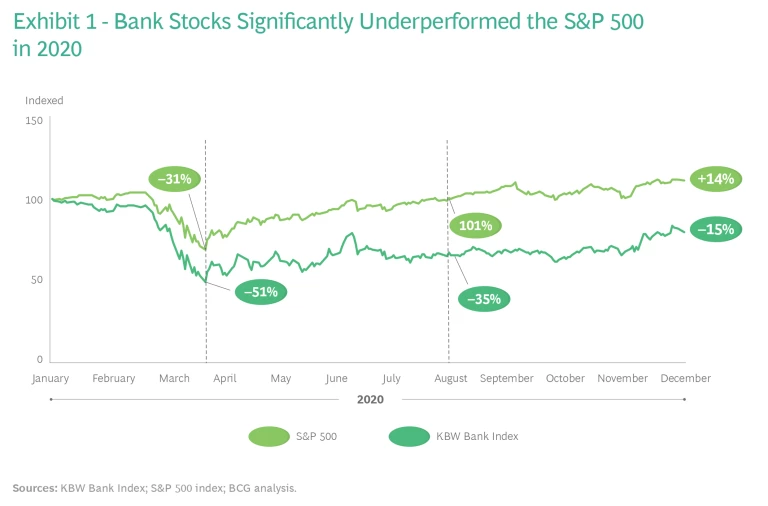

Last year was a grueling one for US banks. While the S&P 500 lost more than 30% by late March, the KBW Bank Index lost more than 50%. In August, the bank index was still down more than 30%, while the broader S&P 500 had already returned to positive territory. (See Exhibit 1.)

Banks responded quickly to the crisis, shuttering branches and laying off staff. According to S&P Global Market Intelligence data, a record 3,324 branches closed in the US in 2020.

This trend is likely to continue. PNC has announced plans to close 280 branches by the end of 2021. U.S. Bancorp, which closed nearly 400 of its approximately 2,800 branches last year, is going to close more this year. Cuts are also underway at Wells Fargo. Having already closed 395 of its 5,032 branches in 2020, the bank announced it was on track to close another 250 branches in 2021.

Banks used similar cost-cutting measures during the financial crisis of 2008, closing thousands of branches and laying off many thousands of employees. Although these moves helped the bottom line, they greatly damaged employee morale and customer sentiment.

Wanting to play a positive role during the current crisis, many financial institutions have participated in the government-backed paycheck protection program and have extended traditional loans to small struggling local businesses. Some banks have even pledged not to lay off employees.

But no bank can afford to operate in the red. As ultralow interest rates and rising loan default rates continue to threaten revenues and profits, banks must find ways to stay solvent—ways that preserve their reputation and the sense of community they have fostered over the years.

Pushing the Procurement Button

Nearly all industries are accustomed to saving money by cutting procurement costs. Not banking, though: at many financial institutions, in fact, the procurement function doesn’t operate independently, and some banks lack one altogether. When a procurement team is used, it often gets involved late in the sourcing process. Viewed by business units as paper pushers, procurement managers are often not allowed to implement controls such as demand management.

Banks that take this kind of approach to procurement are frequently unable to harness the potential cost-savings opportunities. Given that procurement spending is such a large portion of the overall budget, this gap deserves immediate attention.

Taking a Comprehensive Approach

Although it’s often assumed that the chief way to lower procurement spending is to negotiate pricing with vendors, that’s only one lever of many. Banks need to take a more comprehensive approach if they want to deliver really impactful savings.

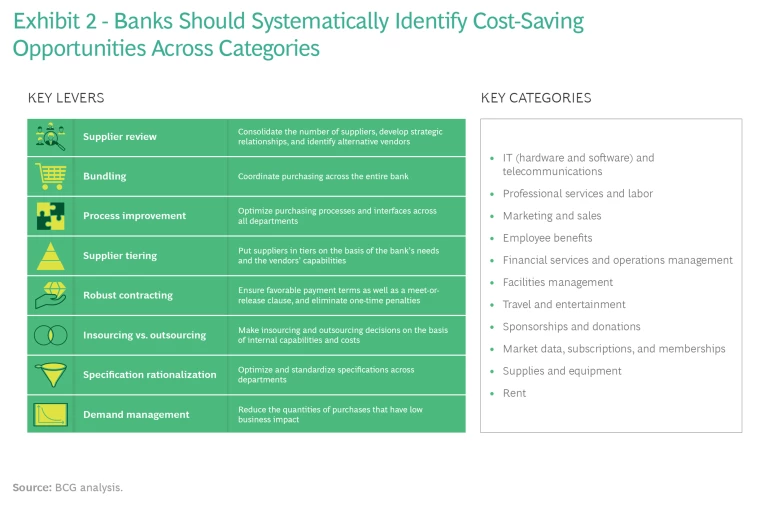

Before a bank even starts negotiating with vendors, it should select a comprehensive set of levers that it can use to identify opportunities to remove constraints and inefficiencies that could be standing in the way of savings. (See Exhibit 2.)

For example, a bank may be buying items with specifications far higher than are actually needed and paying a premium as a result. Additionally, many departments may be purchasing similar items separately that would be much cheaper if bought in bulk. And sometimes the items being purchased are simply no longer used or needed. The process should be a 360-degree assessment of spending that examines both internal and external opportunities.

Finding Savings in Surprising Places

Banks that take a comprehensive approach can find savings where they’d least expect to.

Facilities Management. Janitorial and maintenance services offer a unique savings opportunity. The reason: expenditures for these services aren’t monitored at the enterprise level because they are made by individual branches and are relatively low. But if a bank has hundreds of branches and each branch hires its own janitors and maintenance people separately, there may be hundreds of vendors in all—presenting an opportunity to redistribute the work among fewer vendors.

In addition, instead of treating janitorial and maintenance services separately, a bank could combine these and other related services (such as landscaping, window washing, and carpet cleaning) into one category: facilities management. Then it will be clear how significant the spending is—and the potential for savings.

One bank, for example, discovered that more than 100 vendors were providing facilities management services to its 300 branches. So it identified all related services and determined how often each branch needed each service on the basis of the square footage, the amount of traffic, and other factors. The bank then consolidated the number of vendors to fewer than ten and forged strategic partnerships with them.

These actions made it significantly easier for the bank to coordinate suppliers and harmonize standards across branches, while reducing invoicing and administrative tasks. As a result, the bank was able to reduce its total spending on facilities management by 19% annually.

Telecommunications. An area that can yield significant savings is telecommunications. There are three key types of services—mobile, internet, and analog phone lines. Banks often use a different vendor for each type of service. And sometimes they use many different vendors for just one service. Consolidating all telecom spending with one vendor is a good way to reduce costs.

Consolidating all telecom spending with one vendor and assessing costs for analog lines are good ways to reduce costs.

Banks can reduce telecom spending even more by taking a closer look at their costs for analog lines. These expenditures often aren’t monitored because they are relatively low per branch and because banks are so accustomed to paying for analog lines, even though most branches have already switched to VoIP. So it’s important to determine whether analog lines are still required and, if so, how many.

One bank assessed its telecom expenditures to find that it was sourcing its mobile, internet, and analog phone services from more than 25 vendors. The bank also found that approximately 60% of its analog lines were not even in use. By eliminating these extraneous lines, the bank identified its essential telecom services across all branches and found one vendor to service most of its requirements. With its newly created scale, the bank was able to negotiate better commercial and service terms with its new strategic partner. Through these moves, the bank reduced its annual telecom spending by 34%.

Consolidating phone services is not the only way to cut telecom costs. Banks also should get a firm understanding of their internet needs—the amount of bandwidth and the level of service that’s required in each branch—to avoid unnecessary costs.

Temporary Staffing. Acquiring temp staff is all too often a very decentralized process. Each department typically makes its own hiring decisions and writes its own job descriptions. This approach often results in the same position being described differently and hiring agencies providing the same type of talent to different departments at different rates.

Decentralized hiring can result in different departments paying the same type of talent at different rates.

A bank that was facing staffing gaps collected all the job descriptions for all the temp staff across the organization. This assessment revealed more than 150 job descriptions, many of which were for the same position. The bank harmonized the descriptions so that the same position was described the same way for all departments. This process made it possible to consolidate the number of roles to 24.

The bank then used a competitive request-for-proposal process to negotiate rates and markups for each vendor according to the specific position that needed to be filled and the location (for example, a customer care specialist in New York City). This approach reduced the number of vendors from more than 16 to 5, allowing the bank to realize approximately 30% savings while meeting its talent needs across the country.

Legal. Procurement teams are not usually involved in managing the procurement of legal services. As a result, there are significant savings to be found in this area.

Banks use both in-house counsel and external law firms to meet their legal requirements. To reduce this spending, a bank should first optimize the mix. As a general rule, most routine matters should be handled in-house, while complex, nonroutine matters can be outsourced. A bank can further reduce this spending by harmonizing hourly rates for external law firms by firm tier, the position of each person who performs work for the bank, and the type of matter being handled.

To reduce legal expenditures, most routine matters should be handled in-house.

One bank, for example, found that it was spending approximately 30% more on external law firms than the competition was spending. A deep dive revealed that the in-house legal team was about one-third the size of peers’ legal teams. As a result, the bank was sending more cases to external law firms. Sometimes these were simple and recurring activities related to contracts, agreements, loans, and litigation support that could be easily managed internally. By bringing these matters in-house and augmenting the internal legal team by 30%, the bank reduced its external legal spending by about 10%.

The bank also found wide variations in the hourly rates charged by different law firms. Sometimes partner rates at the same law firm varied by as much as 40%; even rates for the same person varied at different times of the year. Using a structured, competitive process, the bank renegotiated rates for the various firms they used, which reduced external legal costs by another 10%.

Optimizing procurement offers a number of advantages. A bank can see cash start flowing to the bottom line in less than six months, with quick wins in about three months. What’s more, it’s not necessary to repeat the process every year: a bank could be largely set for about three years by locking in contracts for that amount of time. As an added benefit, this minimally invasive approach won’t hurt employee morale and customer relationships that a bank has worked so hard to build.