CFOs say it’s finally time to slay the three-headed corporate budgeting monster.

Is it finally time to slay the three-headed corporate budgeting monster? Many CFOs we talk to think so. They question the effectiveness of a rigid process often fraught with internal conflicts as they try to build resilience and improve agility when responding to unforeseen events. New heights of volatility and uncertainty unleashed by COVID-19 have pushed their frustrations to the boiling point. The C-suite is more open to change than perhaps it has ever been.

Among CFOs , alternative approaches to budgeting are getting a lot of attention. In particular, Beyond Budgeting, a concrete alternative to traditional budgeting, is gaining mainstream traction. The approach is producing impressive results at a growing number of global companies, including Handelsbanken, Bayer Pharmaceuticals, Volvo, Equinor, and Roche Pharmaceuticals . Moreover, a December 2020 BCG study confirmed that Beyond Budgeting has significant benefits: 59% of 174 finance executives surveyed reported increased sales, 56% saved significant costs in the budgeting process, and 41% freed up formerly held back financial resources. At the same time, respondents reported important improvements in organizational effectiveness, such as better business decisions (52%), more effective performance management (51%), and greater agility in reallocating resources (45%).

Conflicting Purposes

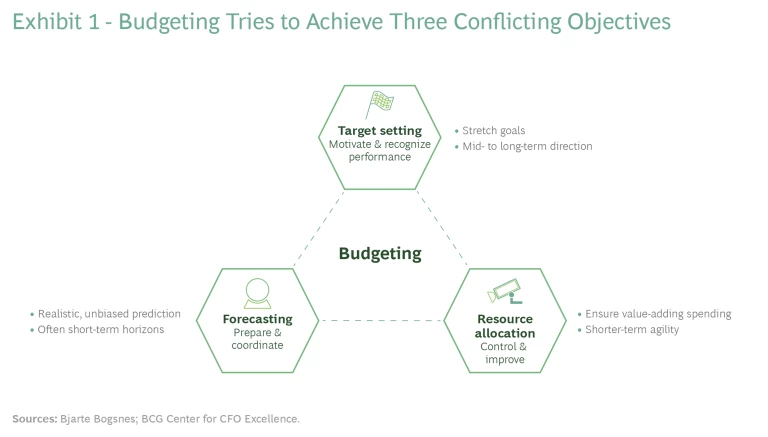

Traditional budgeting is like trying to square a circle, because the process tries to meet three ultimately incompatible objectives. (See Exhibit 1.) First, budgeting sets targets to motivate and promote performance. These targets require directional and stretch goals. Second, budgeting provides forecasts of what lies ahead, but the forecasts only work if they are realistic, unbiased predictions. Production, for example, has to know what the expected sales are, as opposed to the stretch targets that sales strive to meet . In addition, the timeframes for useful forecasts can often be longer or shorter than the one year set by most budgets. Third, budgeting allocates resources by setting boundaries around future spending so that management can control costs and intervene to cut them when necessary. The C-suite typically tries to ensure that resources are allocated to the most value-creating opportunities while preserving short-term agility.

Given these conflicting objectives, it’s no wonder that companies often fail to achieve them with the same instrument at the same time. The traditional budgeting process leads to a long list of problems and challenges , ranging from the significant cost and effort required to create the budget to counterproductive motivations, unrealistic targets, gaming, and year-end spending fever.

The Beyond Budgeting movement has distilled 12 principles that form the basis of its approach, 6 regarding leadership and 6 regarding management processes. (See “The Principles of Beyond Budgeting.”) Together, they are meant to help organizations create a comprehensive and consistent new steering model. Companies that have implemented Beyond Budgeting have slain the corporate budgeting monster. They have stopped traditional budgeting and achieved each of the three objectives separately and in new ways.

The Principles of Beyond Budgeting

- Leadership

- Purpose. Engage and inspire people around bold and noble causes, not around short-term financial targets.

- Values. Govern through shared values and sound judgment, not through detailed rules and regulations.

- Transparency. Make information open for self-regulation, innovation, learning, and control; don’t restrict it.

- Organisation. Cultivate a strong sense of belonging and organize around accountable teams. Avoid hierarchical control and bureaucracy.

- Autonomy. Trust people with the freedom to act. Don’t punish everyone if someone abuses that trust.

- Customers. Connect everyone’s work with customer needs. Avoid conflicts of interest.

- Management Processes

- Rhythm. Organize management processes dynamically around business rhythms and events, not around the calendar year only.

- Targets. Set directional, ambitious, and relative goals. Avoid fixed and cascaded targets.

- Plans and Forecasts. Make planning and forecasting lean and unbiased processes, not rigid and political exercises.

- Resource Allocation. Foster a cost-conscious mindset and make resources available as needed, not through detailed annual budget allocations.

- Performance Evaluation. Evaluate performance holistically and with peer feedback for learning and development, not based on measurement only and not for rewards only.

- Rewards. Reward shared success against competition, not against fixed performance contracts.

Directional and Relative Target Setting

With Beyond Budgeting, companies still set targets, but they are typically directional, relative, and established by the business units themselves. The level of detail is also much lower than that of a typical budget.

Top-level metrics, such as revenue, EBIT, or ROCE, are all effective targets, especially when compared with peers and complemented with relevant nonfinancial metrics. Ratios, such as unit costs, are typically more meaningful than absolute numbers. A company can instill stretch motivations by defining targets relative to internal or external benchmarks. These targets motivate and steer performance by articulating a clear purpose, ambition, and strategic direction. Roche, for example, places a strong emphasis on openly communicating strategy as a guardrail for performance. Ultimately, a strong performance culture guides day-to-day decision making.

Targets should have time horizons dictated by need and circumstance: shorter if there is urgency (a turnaround situation, for example) and longer if required by goals or complexity (entering a new market or starting a new venture). End of December deadlines become the exception more than the norm.

Given the conflicting objectives of traditional budgeting, it’s no wonder that companies often fail to achieve them with the same instrument at the same time.

Some companies go even further. Handelsbanken, a Swedish bank with 700 branches in multiple countries, does not set targets. The company aims to deliver return on equity higher than the average of its competitors, and it has achieved that goal every year since 1972—two years after management booted the budget. Branch performance is measured not against targets but against comparable branches—on cost-to-income ratios, for instance. Alternatively, a branch might set a target itself. The branch managers are trusted to know best how perform well against peers. To avoid unhealthy internal competition, there are no individual bonuses, just a common bonus scheme for all employees, driven by the bank’s performance against the competition. This stimulates collaboration and sharing of best practices across the bank.

Unbiased, Decision-Centric Forecasts

We all know what happens when leadership asks for revenue projections from unit managers who are fully aware that the number they submit will serve as the basis for a target, often with a contingent bonus attached. Or when finance requests capex and opex numbers, and everybody knows that this is their one chance of getting access to next year’s resources—and that whatever number they submit will most likely be reduced. A forecast should be neither an opening bid in a target negotiation nor an application for resources. Forecasting should be its own separate process, dedicated to producing a realistic prediction of future performance.

The distinction between targets and forecasts becomes clear when the first forecast is completed. If it is below target, that does not mean the target cannot be met. Rather, the unbiased information that the forecast provides serves as a basis for determining the actions required to achieve the target. Finance has an essential role to play in framing and preparing management discussions accordingly.

The objective is to support good business decision making in areas such as short-term production capacity planning or long-term investment approval. Forecasts should be made for the time horizons relevant to the decisions at hand—which are not necessarily one year—and they should be updated as often as needed. Because the outside world moves quickly, most companies need to look ahead more frequently than once a year—at least quarterly, if not more often. Many companies use quarterly rolling forecasts with a five-quarter time horizon. Usually, forecasts are less granular than in prior budgets, because they are not conducted as a detailed, bottom-up exercise.

Best-in-class forecasting leverages algorithms to create unbiased predictions and provide managers with solid feedback on the impact of actions and initiatives already underway. Daimler Mobility has built a forecasting engine to produce monthly high-quality forecasts without expending prohibitive amounts of extra effort. Leaders are allowed to overwrite the algorithmic forecast to reflect information that the central engine was not able to incorporate. Changes in forecasts show whether an initiative actually affects performance. They foster discussions that focus on needed forward-looking action rather than on explanations or excuses for past results.

Companies that have stopped traditional budgeting have achieved each of the objectives of budgeting separately and in new ways.

Some companies—such as the energy company Equinor—have switched to dynamic forecasting, which operates around a few predefined time horizons. Forecasts are created when circumstances change, and they support specific business decisions. Local units renew their forecasts when something happens that they believe requires an update. A common forecasting database enables the group to aggregate a companywide forecast, when needed, by tapping into the latest data.

Broad and Transparent Resource Allocation

Instead of defining rigid, top-down spending envelopes a year in advance, companies that use a Beyond Budgeting approach address resource allocation by combining broad target setting with better reporting. This allows them to delegate detailed decisions to the operational level, where the understanding of what’s required is clearest and resources can best be allocated in an agile way. Management can also issue burn-rate guidance that provides clarity on recommended cost levels.

More freedom and flexibility come with more accountability. To control and safeguard performance, finance sets up a transparent performance monitoring process that allows for quick intervention if needed. Reporting numbers in accounting-like detail usually does not achieve performance transparency. Instead, ratios, trends, and benchmarks for key business drivers provide easy visibility into where costs are moving in the wrong direction. For example, control charts, which track actual results against a trend or an average, are an effective way of monitoring cost development. Variances are investigated if they move outside of statistical control limits, effectively distinguishing signals (to be probed) from noise (to be ignored). Discussions between finance and managers should move from the descriptive (“Costs have increased by 20%”) to a focus on the drivers of costs and what can be done about them.

A company that uses Beyond Budgeting allocates capital dynamically rather than a year in advance. It typically replaces the traditional capex budget with a more continuous decision process, which also keeps one eye on the latest financing capacity forecast. In this way, the bank is always open to funding promising ideas or ventures.

Transparency on spending can become a “social” control mechanism that is highly effective at keeping value-destroying costs at bay. The Norwegian IT company Miles, for example, has no budgets (and no targets), including for travel and training. Employees can attend any course or conference they want. But when they return to work, they have to post on the company’s intranet where they went, what they did, and what it cost. Similarly, Netflix’s expense policy does not focus on detailed budgets but consists of a single sentence: “Act in Netflix’s best interest.” Expense transparency reveals any misconduct and ensures that people adhere to this principle.

Making the Change

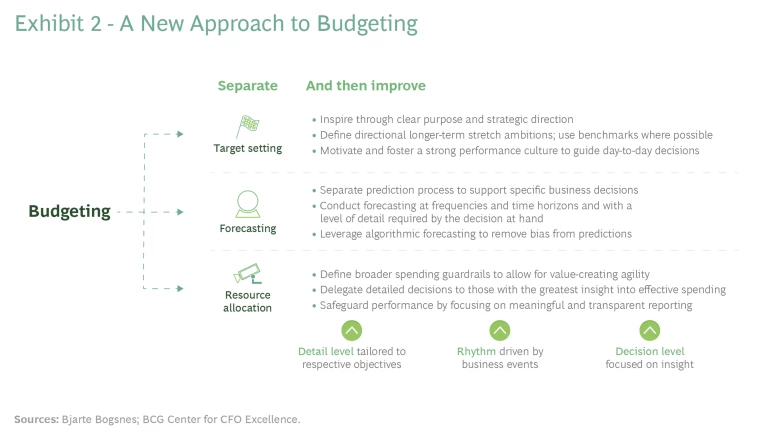

Abandoning traditional budgeting is more of a journey than a one-time decision. We recommend a three-step approach: create the case for change, separate the budget objectives, and improve each process individually. (See Exhibit 2.) There will also inevitably be barriers to overcome.

Articulate the case for change. Most companies start by identifying all the issues that managers have with the current budgeting process using surveys and interviews. The results can make for surprising reading for the executive team, as pain points turn out to be not merely irritating but symptoms of larger systemic issues.

Management needs to define a clear vision of what it wants to achieve and how Beyond Budgeting can solve identified challenges. This will provide motivation for the business and finance teams tackling difficult change and ensure that all the various measures are moving in the same direction.

Separate and improve. Separating the three budgeting objectives is the next step. CFOs need to establish distinct processes and practices for each one—target setting, forecasting, and resource allocation. One of our clients renamed the existing forecast “Predict” to ensure a common understanding of what those numbers really mean. For those that find it nearly impossible to operate without a budget, remember that all the purposes of a budget will still be fulfilled—but in much more effective ways.

To make this kind of journey bear fruit, finance executives need to adopt a systems-thinking approach. Reducing the granularity of targets is only possible with better reporting, for example. Without performance transparency, management will have a hard time delegating responsibility. Changing processes can require changes in leadership style and the promotion of new values such as empowerment, trust, openness, and transparency. Consistency between words and actions, between management’s messages and management processes, is essential. Preaching autonomy and empowerment has little credibility if people remain bound by detailed travel budgets.

Overcoming the barriers to change. Organizational changes are always challenging. The three biggest barriers to implementation of Beyond Budgeting cited by executives in our 2020 survey were concerns about higher costs (46%), implementation risks (44%), and limited board support (33%). These concerns need to be addressed.

Concerns about higher costs arise from the management myth that without budgets, costs will rise and performance will suffer. The truth is that value-added spending might rise. It’s common to see a change in the cost mix, from less value-eroding costs to more value-creating costs. Also, if managers no longer need to maximize budgets in negotiations, the incentives that lead to year-end spending fever disappear. Many companies actually report cost decreases once the budget floor is abolished. In 2020, a public-sector organization in Norway ran a pilot allowing two of its units to operate without cost budgets. Because of COVID-19’s impact on travel and external activities, costs fell in all units, but none dropped as much as in the two pilots, which reported declines of 50%.

Abandoning traditional budgeting is more of a journey than a one-time decision. Management needs to define a clear vision of what it wants to achieve and how Beyond Budgeting can solve identified challenges.

As for implementation risk, history shows that very few organizations go back once they have started, which should be a clear indication that this risk is low. And if things should go wrong, the old process can be quickly reinstated. No one will have forgotten how to budget. The downside risk is minimal compared with the huge upside potential.

We also recommend applying an agile approach: prototype, test, learn, and adjust. Run pilots in certain business units, if relevant. This will ensure demonstration of early benefits via quick wins, which in turn will create buy-in for more daring changes.

A skeptical board is an understandable concern. But this is often fueled by a second management myth: that budgets provide control. In fact, while having the next year described with accounting precision might sound safe, the only thing we know for sure is that the budget will be wrong. The fact that variances can be explained does not mean that managers have control. More often than not, variances are caused by bad planning assumptions or unforeseeable events. Detailed budgeting a year in advance can actually undermine the agility that many boards strive for in the current business environment. Beyond Budgeting gives CFOs the opportunity to make their companies more agile.

Finance is often the greatest enemy of Beyond Budgeting, which challenges its traditional role and accustomed practices. However, practice shows that the Beyond Budgeting approach actually makes finance people’s job much more meaningful. While the overall effort does not necessarily change, the work becomes more future- and business-oriented. The usual autumn sprint is replaced by a more continuous, and arguably a more manageable, process.

Beyond Budgeting has proven to be not only effective, but in many ways superior to traditional processes. This is especially true in today’s uncertain and volatile business environment. Many large organizations have successfully made the change. It is also a model that can serve as a window into what future financial management can look like. But remember: Beyond Budgeting involves not just a change in process but also in how management thinks about the future and about managing people. Managers shift from politburo-style central planning and command-and-control decision making to directional guidance, delegation, and trust. CFOs should plan carefully for the change and the journey.