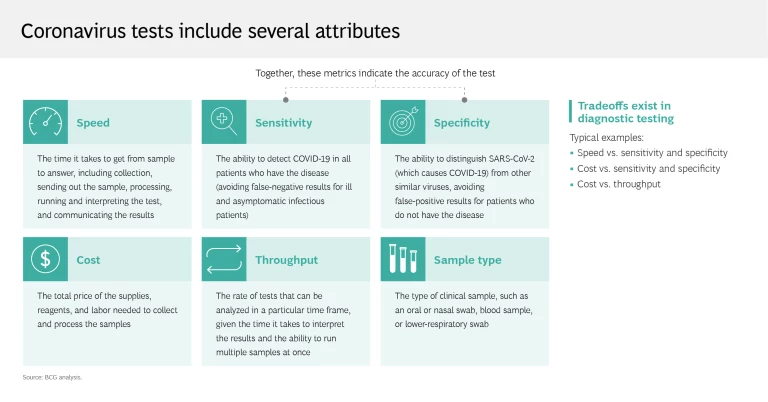

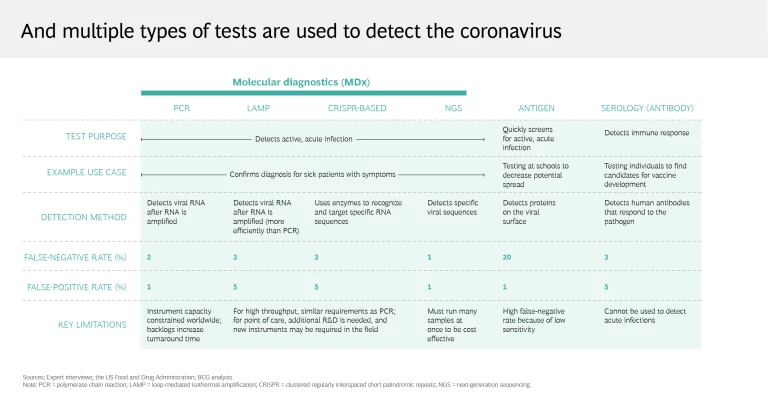

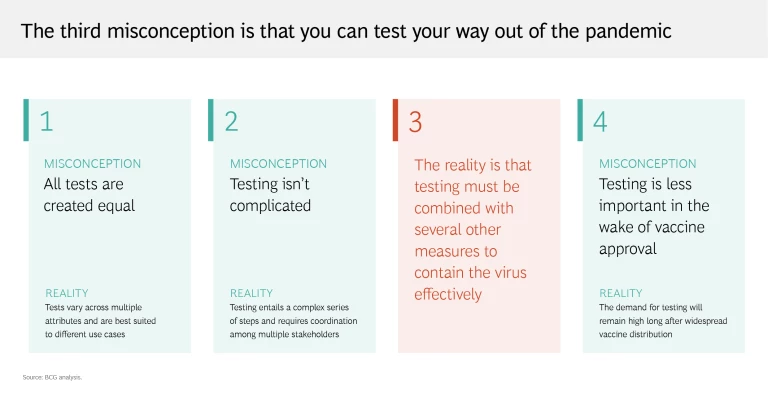

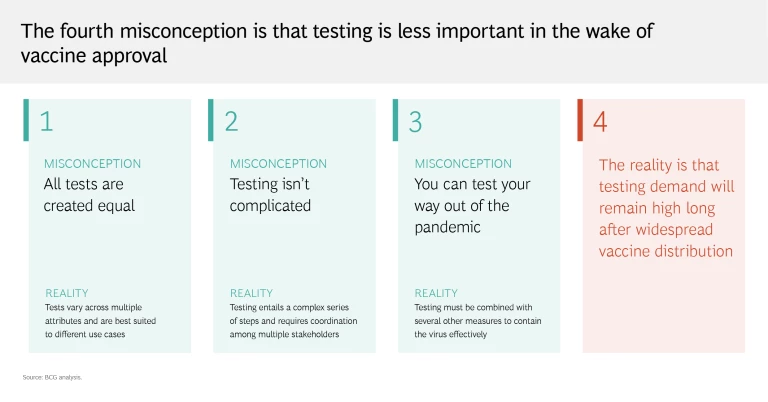

Reality: Tests vary across multiple attributes and are best suited to different use cases

There’s a lot more to testing than deciding whether to use a nasal or throat swab. Coronavirus test attributes include speed, sensitivity, specificity, cost, throughput, and sample type—and different testing modalities are best suited for certain use cases. For example, the molecular polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test, considered the gold standard, is highly sensitive and specific, making it ideal for diagnosis and triage. But it takes time to process the test, which requires laboratory analysis, so PCR is less effective in population health surveillance. Conversely, the speed with which the rapid antigen test can deliver results makes it the test of choice for identifying the prevalence of the coronavirus in a given region, even though the test is more likely to produce a false negative.

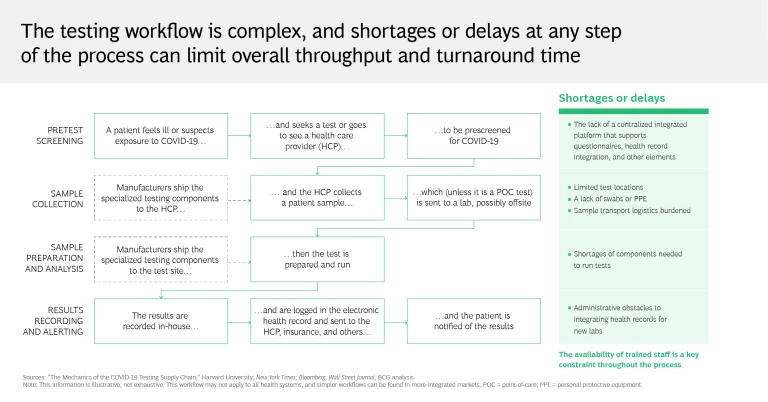

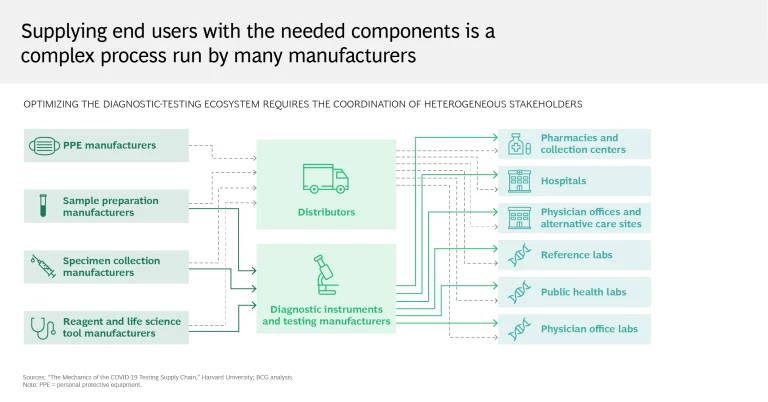

Reality: Testing entails a complex series of steps and requires coordination among multiple stakeholders

It can seem simple enough: you’re administered a test by your local health care provider, who sends your sample to a lab, which in turn reports the results. Some tests can even yield results in 15 minutes, without further analysis or intervention. But this perspective takes for granted all the work that goes on behind the scenes.

A testing workflow is a highly complex process that requires coordination among many stakeholders—hospitals, pharmacies, equipment distributors, life sciences companies, and laboratories among them. Shortages or delays at any step can limit throughput and turnaround time, which in the current global context of strained supply chains, inconsistent testing practices, and a stretched-thin medical community has proved a challenge for many governments and health care systems. Testing centers depend on swabs and personal protective equipment, just as labs rely on critical components for determining the presence of the virus. Trained staff are needed across the entire process, from sample collection to results reporting.

What’s more, new technologies intended to improve testing efficiency and effectiveness still face implementation challenges. Wastewater surveillance, for example, could be used to monitor community spread by enabling early detection of viral changes in a broad population, but this would require new sampling methods and addressing the issue of decentralized wastewater systems. In other words, although new and improved testing methods are on the horizon, each poses its own set of obstacles.

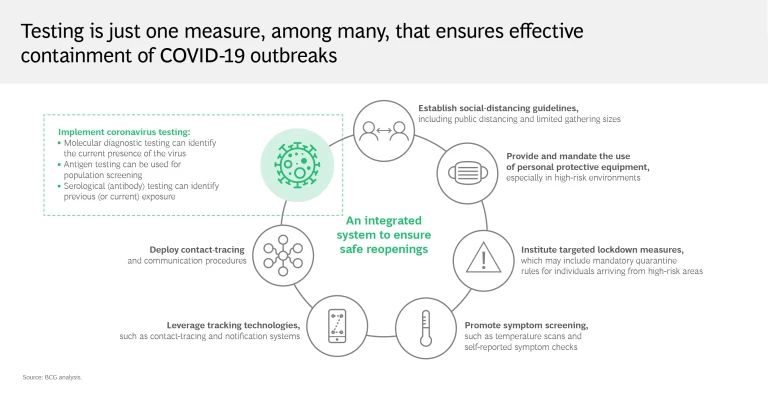

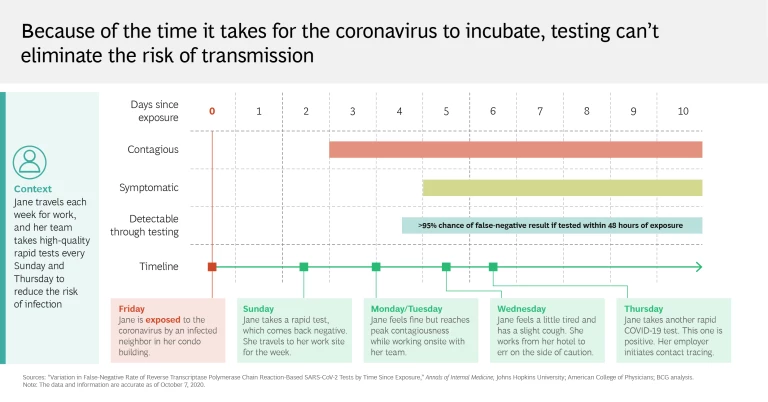

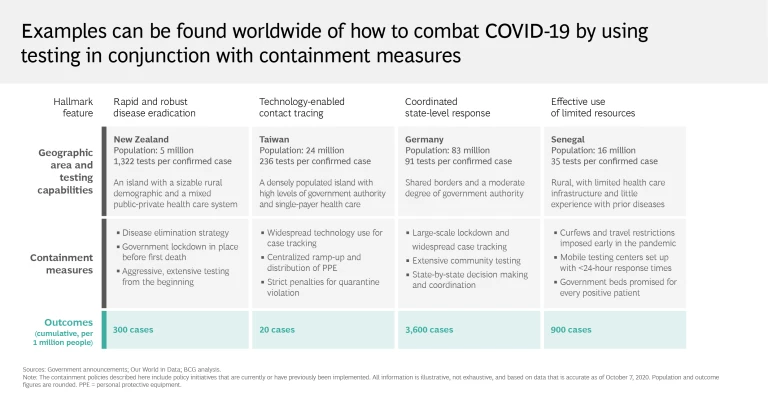

Reality: Testing must be combined with several other measures to contain the virus effectively

It’s an all-too-familiar story. Someone tests negative on Monday, feels sluggish on Tuesday (or doesn’t), and goes to an event on Wednesday—while at the same time unwittingly spreading the coronavirus. This can happen because a test result reveals only whether the virus was detectable at the time of sampling. It does not confirm with absolute certainty that the person who took the test hasn’t previously been exposed to the coronavirus, nor does it give any assurances against further contact (which could conceivably occur on the way home from taking a test or even at the testing center itself). What’s perhaps most troubling is that the efficacy of testing on asymptomatic patients, who are nevertheless contagious, remains unclear.

As these limitations show, testing alone clearly isn’t enough to put an end to the pandemic. Regions and health systems that have largely crushed and contained the virus know that for testing to be effective, it must be carried out aggressively and supplemented with an integrated mitigation system. Social distancing, tech-enabled contact tracing, and the broad distribution of personal protective equipment are critical to this effort, as are targeted lockdown measures. Organizations must implement symptom screening and promote self-reporting to ensure employee safety and operational continuity.

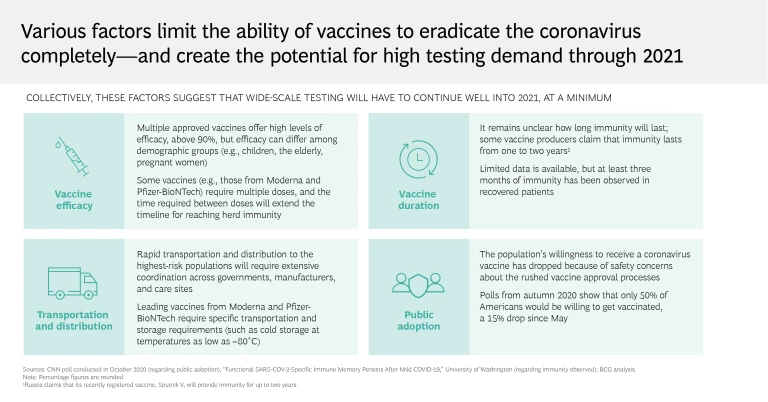

Reality: The demand for testing will remain high long after widespread vaccine distribution

The good news is that the distribution of highly effective vaccines is already underway, and we expect to see additional vaccines approved for use in the coming months. Considering earlier forecasts of vaccine efficacy and timing, this is the best-case scenario from a development perspective. But we’re not out of the woods yet, and testing will remain critical .

Widespread vaccination is likely to take many months, or even years, and many countries are falling short of their initial distribution goals. Despite the vaccines’ initial promise, it’s uncertain whether they can prevent asymptomatic spread or for how long they will provide protection from the virus, meaning that populations could require multiple doses over time. It’s also unclear if current vaccines will provide the same level of immunity for everybody, or if some demographics, such as children and the elderly, will require additional protections. Further complicating matters is the skepticism that many feel toward the efficacy and safety of vaccines, which could hinder global efforts to achieve herd immunity.

Accordingly, workplaces and governments will have to rely on testing for the foreseeable future—with peak demand likely to occur in the seasonally affected first quarters of 2021 and 2022. Although we expect testing volumes to decline after 2021, we anticipate a continued need for testing in the next few years as the disease enters a more endemic phase. Businesses should also keep mask mandates in place and continue contact-tracing programs to curb the spread.