The number of people willing to move abroad for work has declined. The US has lost its status as the world’s most popular work destination. And just about everybody’s view of work has been reshaped, in one way or another, by the pandemic.

These are among the findings of a new survey of almost 209,000 people in 190 countries. The survey, by Boston Consulting Group and The Network, shows a very different set of attitudes toward mobility than the one that prevailed a few years ago.

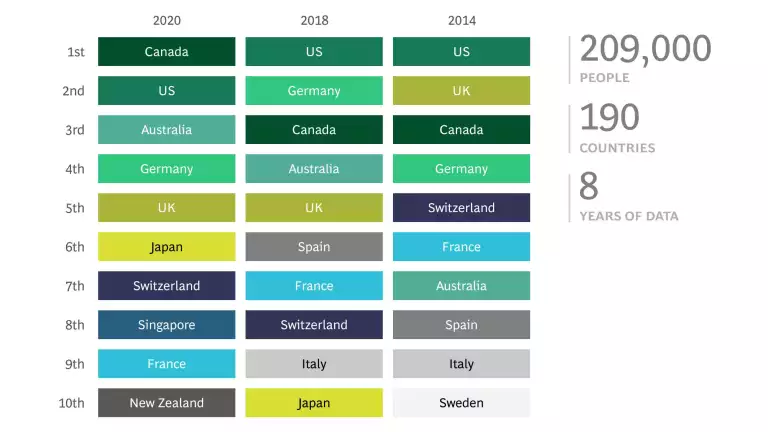

Top Work Destinations

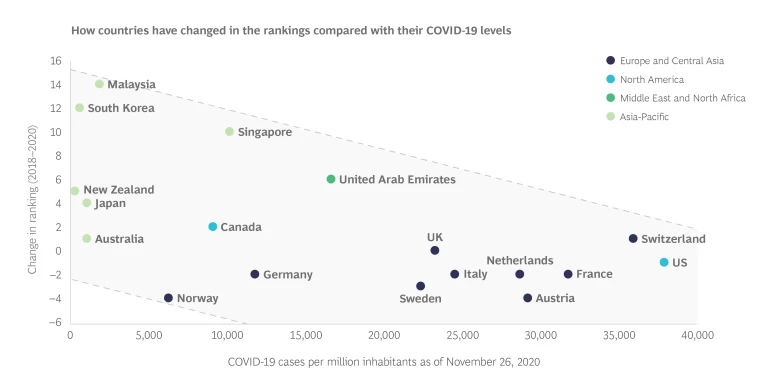

The changes to the list of top-ten destinations largely reflect different countries’ success in managing COVID-19 outbreaks. Almost all of the countries that have fallen lower on the list or disappeared from it—including the US, France, Italy, and Spain—have struggled, at some point in the last year, to “flatten the curve.” Europe’s public health struggles may have also affected Germany, a better pandemic manager whose ranking nevertheless declined.

By contrast, for countries that have managed the coronavirus effectively, there has been a popularity boost. That is true of several Asia-Pacific countries, including Japan, which jumped four places, and Singapore and New Zealand, which weren’t on the list in 2018 but are now. Strong coronavirus management has also helped Canada, which has moved ahead of the US to become the number-one work destination globally.

Besides being number one overall, Canada is also the first choice for those with master’s degrees or doctorates, for those with digital training or expertise, and for those younger than 30. These are characteristics that companies and countries prize.

Lower Overall Willingness to Relocate

When we conducted our first survey about people’s willingness to move to another country for work, in 2014, almost two-thirds of global respondents said the idea appealed to them. The proportion has declined by 13 percentage points since then and is now about 50%.

Clearly, it isn’t only the pandemic that has weakened the mobility trend. More restrictive immigration policies and social unrest are also factors. (This year’s study is being presented as a three-part series. This first report on mobility will be followed by publications on

changing work models

and shifting career expectations in the era of COVID-19.)

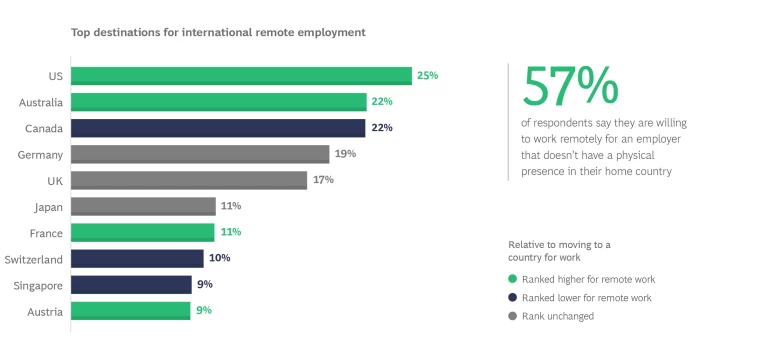

“Virtual Mobility” Is on the Rise

Even as the willingness to move abroad for a job has declined, a new model has emerged, relating to remote international work and growing out of the trend of distance work during COVID. Fifty-seven percent of respondents say they are willing to work remotely for an employer that doesn’t have a physical presence in their home country, a level that is well above the proportion who are open to physical relocation.

Indeed, when the question is about working for a foreign employer remotely versus having to move to a country where the employer has physical offices, the preferred destinations shift in some interesting ways. The US is the most desirable destination under this scenario, suggesting that American employment retains a lot of appeal if you take away the political and social risks that come with living in the country.

The overall openness to virtual work may be of particular interest to employers, especially the many employers that struggle to fill jobs in the IT and digital fields. Remote international employment does present challenges to companies, such as cultural integration and administering salaries in regions with different costs of living. But these obstacles can be overcome, as some companies are already demonstrating.

Download the full 2021 report to understand the state of virtual mobility and explore the trends that are shaping the workforce of tomorrow.