Growing demand for hydrogen will impact transportation and distribution networks differently. Players must plan ahead if they are to successfully navigate the coming disruption.

The energy transition raises questions for midstream gas players. Most crucially, since clean energy is set to replace fossil fuels in the coming decades, what happens to the regulated pipeline businesses that provide the infrastructure to carry natural gas? Here’s how we see it.

Growing demand for hydrogen and other low-carbon fuels will create opportunities for pipeline operators and owners. But how these play out will vary, depending on the type of network. Companies operating long-distance transportation pipelines that connect supply points with areas of demand could be relatively unaffected by the shift toward cleaner alternatives as their pipelines are repurposed to carry hydrogen.

By contrast, operators of distribution networks that deliver natural gas to homes and smaller businesses could see a significant decline in volumes as a result of electrification and customer efficiency measures. But the level of disruption across their networks will be uneven, with location, customer mix, and the availability of low-carbon fuels all playing important roles.

Looking ahead, the previously safe and predictable midstream gas sector is set to experience significant change. Although the full effects of declining natural gas demand may not be felt for some time, pipeline operators, owners, and regulators need to prepare now. Operators and owners will have to make vital decisions about where to invest for future growth and which parts of their networks to ax. And they will need to work with policymakers and regulators to draft new rules to smooth the transition toward low-carbon fuels.

The Outlook for Natural Gas

In recent decades, demand for natural gas has grown faster than for any other fossil fuel, and natural gas now accounts for almost a quarter of the world’s total primary energy demand. Because it is cleaner than other fossil fuels, natural gas has an important role to play as a transitional fuel to a net-zero world. Consequently, overall global demand for the fuel is likely to increase for the next several years. But growth will be increasingly uneven. Natural gas demand in some regions and in some consumer segments will reach a tipping point and start to decline before 2030.

Despite its environmental benefits relative to other fossil fuels, natural gas faces gradual replacement by low-carbon solutions in all major gas segments as energy efficiency and decarbonization initiatives accelerate. In power generation, a combination of renewable energy and batteries will be the dominant technologies supplanting natural gas. In industrial uses, hydrogen and, to a lesser extent, other low-carbon fuels will take over. And in heat generation, decarbonized district heating and electrically powered heat pumps will play a major role in reducing demand for natural gas.

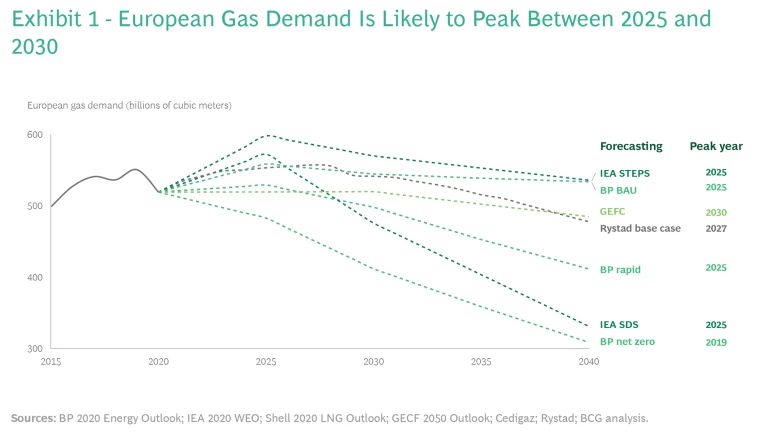

Europe and other regions with a strong commitment to decarbonizing their economies, including Australia and some parts of the US, will lead the way. Most forecasters predict that European gas consumption will peak around 2025, ahead of all other parts of the world. (See Exhibit 1.)

In these three regions, aggressive policy initiatives will affect—or already are affecting—gas consumption:

- In the EU, policymakers are introducing tougher energy performance standards for buildings, as reflected in the building regulations of many member states (such as RT2020 in France).

- The UK plans to install 600,000 heat pumps in homes each year by 2028 and to ban gas-fired boilers in newly built houses starting in 2025.

- In the Netherlands, cities have been removing neighborhoods from the gas grid since 2018.

- In Australia, certain city councils have announced plans to ban new gas connections.

- In the US, several states, including California and Washington, are promoting electrification and curbing the use of natural gas in buildings. But other states, including Oklahoma, are resisting federal-level pressure to ban gas usage in buildings.

Natural gas pipeline players in Europe, Australia, and the West Coast of the US face the greatest near-term changes to their networks from falling consumption. Complicating matters, the rate of decline in natural gas consumption will not be the same in all segments. Residential usage will see the biggest impact, as a result of increased home insulation and of government policies that promote replacing natural gas boilers with electrically powered heating systems.

Power generation and industrial companies—especially those that use natural gas for high-grade heat and as chemical feedstock—will take longer to change to alternative fuels. But over time, only companies that can use carbon capture technologies to sequester the CO2 emissions from natural gas combustion, and improve their financial standing by doing so, are likely to continue to be significant natural gas customers.

In power generation, natural gas will remain an important fuel because gas-fired plants can provide flexible backup power when renewable energy sources are down. Demand for natural gas might even rise temporarily as the electrification of transport and heating, combined with the retirement of coal plants, increases the need for gas-fired power plants. But in the long term, the amount of gas-fired power generation must drop if we are to achieve net-zero emissions worldwide by mid-century.

How These Trends Will Affect Networks

The developments noted above will play out differently for different types of gas networks.

Transportation Networks. In general, although declining natural gas volumes will impact operators of high-pressure transportation pipelines, the energy transition will create opportunities for these companies in two important areas.

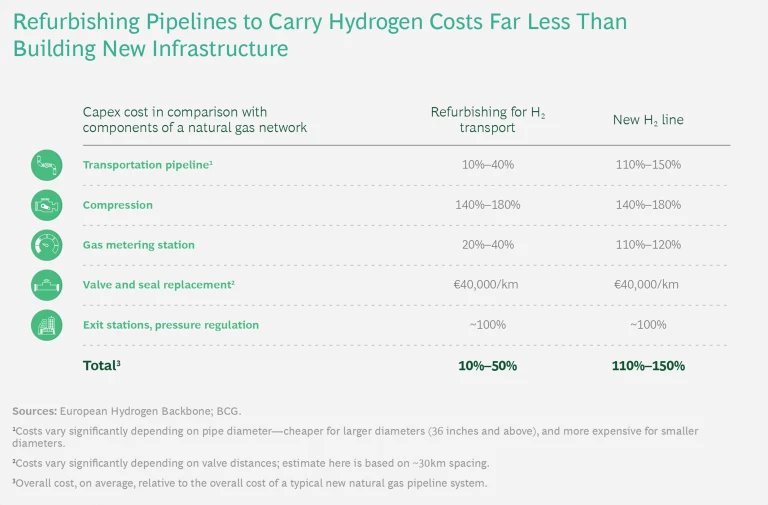

First, transportation pipeline operators will play a crucial role in providing the midstream infrastructure for new low-carbon fuels such as hydrogen. In all cases where companies have a choice, they will find it cheaper to retrofit existing pipelines to carry hydrogen than to build new ones. According to the European Hydrogen Backbone, an initiative set up by 23 gas infrastructure companies, repurposing high-pressure pipelines costs one-third of the one-off investment expense, and 30% to 50% of the full-life cost of an entirely new network. (See “Preparing Gas Networks for Hydrogen.”)

Preparing Gas Networks for Hydrogen

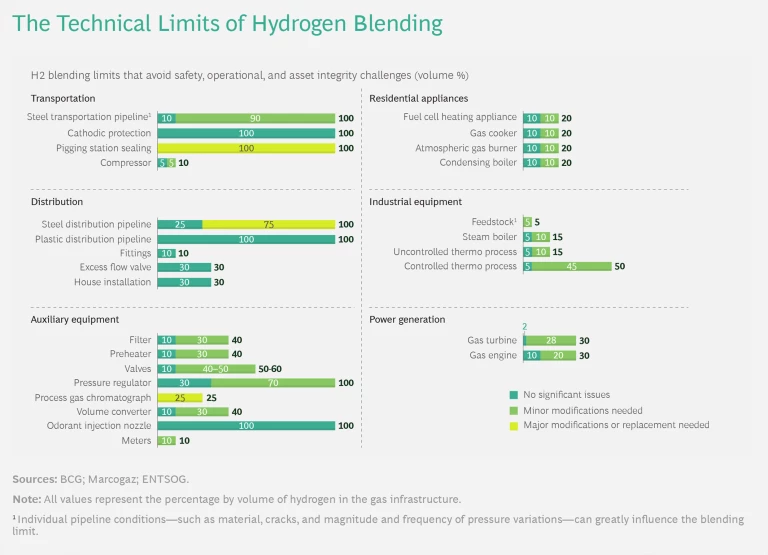

Pipelines. Hydrogen accelerates pipeline degradation by penetrating the metal content and reducing its ductility (a process called hydrogen embrittlement). Depending on the steel used and the pipeline’s condition, the pipeline’s inner surface may be protected with a special chemical coating so that it can transport or distribute hydrogen without embrittlement taking place. The cost of this process is from 10% to 40% of the cost of building a new natural gas pipeline. (See the exhibit.) One alternative is to reduce the pressure in existing steel pipelines and carry out diagnostic checks more frequently. Even with these measures in place, however, pipelines are likely to have a shorter useful life than refurbished or new hydrogen-specific pipelines. Operators can protect new hydrogen-carrying pipelines from embrittlement by using lower-grade, more-ductile steel, or by treating them with an inner coating. But such pipelines will be 10% to 50% more expensive than new untreated natural gas pipelines.

Valves and Seals. To avoid hydrogen leakage, operators must change the network’s valves and seals. The standards and condition of gas network assets vary from one region to the next. For this reason, some operators will need to replace only a proportion of their valves and seals, while others will need to replace all of them.

Compressor Stations. Because hydrogen’s calorific value is about one-third that of methane (a primary component of natural gas), operators will have to increase volume flow by reducing and managing pressure levels at the exit point. This step can cause the amount of energy that a hydrogen pipeline transports to reach 80% of that of a natural gas pipeline. But doing so involves retrofitting or replacing equipment to increase compressor capacity. We estimate that, in the case of refurbished and new hydrogen-carrying pipelines, such investments add up to the equivalent of 40% to 80% more than the cost of installing compressors for a new natural gas pipeline.

Exit Stations and Meters. In networks that carry a lot of hydrogen, operators will have to replace natural gas meters with equipment calibrated for the new gas. For a gas pipeline refurbished to carry hydrogen, the cost of recalibrations and partial replacements is around 20% to 40% of that required for a new natural gas pipeline. But the corresponding cost is far higher for a new hydrogen-carrying pipeline—approximately 10% to 20% more than for a new natural gas pipeline. But costs related to metering and exit station components are still relatively small compared with total system costs.

Operators of distribution networks need to take six components into account: valves and seals, fittings, pressure regulators, meters, monitoring equipment, and pipelines. In preparing the first four components for use in hydrogen transport, companies must either replace existing infrastructure or carry out retrofits so that current components are fit for their new purpose. Entirely new systems and equipment will be necessary for monitoring and detecting leaks in middle- to low-pressure networks. With steel and iron pipes, replacement is likely to be the most effective solution. Polyethylene pipes, however, won’t require changing in order to distribute hydrogen.

Whether they need to build afresh or alter their current networks, existing gas transportation pipeline operators have deep experience and consequently are the clear favorites to build and run hydrogen midstream infrastructure.

Second, remaining natural gas usage will be concentrated primarily among companies that require significant volumes of the fuel, such as power generation and industrial users. These large players can deploy carbon capture technologies to sequester emissions, so some could continue to be natural gas customers over the long term. Most of them will get their natural gas directly from transportation rather than through distribution pipelines.

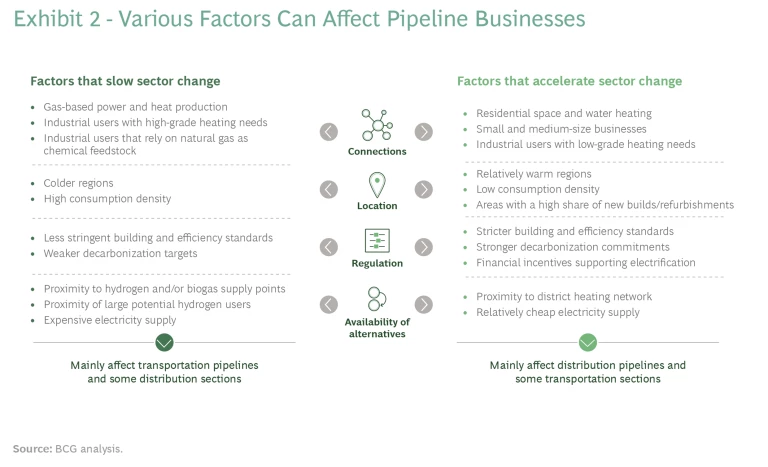

Distribution Networks. Pipelines that take gas from the transportation network and deliver it at lower pressure to residential areas and smaller businesses via a widespread network are likely to see their volumes decline more steeply. Several key factors underlie this probability. The electrification of heating, energy-efficiency measures and policies aimed at curbing the use of natural gas, and a warmer climate will all contribute to reduced demand. For smaller gas consumers, hydrogen is less likely to be an effective substitute for natural gas. In many instances, district heating or individual electricity-based heating offers better long-term economics. Hydrogen-based heating is preferable only in situations where these other approaches are unfeasible, owing to such factors as lack of space or financial resources. Biomethane may offer another alternative utilization of distribution networks, but its use will be limited to areas that are close to sources of sufficient supply, such as from agriculture. The impact of these developments, however, will vary from one player to the next—and even within networks. (See Exhibit 2.)

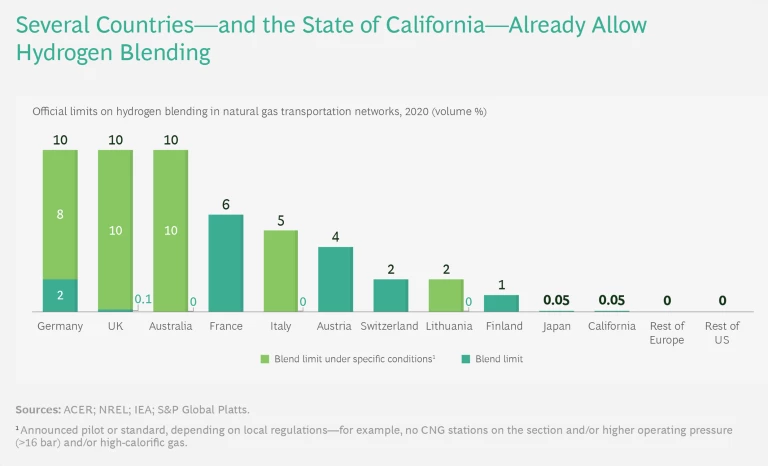

As demand for cleaner fuels grows, blending low-carbon fuels with natural gas will be an essential transitional step for transportation and distribution network companies. Blending will also allow them to develop valuable capabilities in handling and accessing future fuels such as hydrogen.

Several countries already allow pipeline operators to carry blends that are up to 6% (by volume) hydrogen—and up to 10% under specific conditions. Industry studies and pilot projects indicate that existing natural gas networks can even accommodate blends containing as much as 20% to 25% hydrogen, with moderate investments on the user and operator sides, before safety, operational, and asset integrity considerations become significant issues. (See “The Challenges of Blending Hydrogen with Natural Gas.”) Studies are also underway to examine the feasibility of deblending technology, which would separate blended hydrogen and natural gas into homogeneous streams once the blended gas arrived at its destination. There is no comparable limit to the percentage of biomethane that can be blended with natural gas. But supply constraints are likely to prevent biomethane from being a viable candidate for high-ratio natural gas blends.

The Challenges of Blending Hydrogen with Natural Gas

Blending will be an essential first step toward increasing the share of hydrogen in natural gas networks, but it poses some challenges. Considerations of safety, operational limitations, and asset integrity drive current blending limits. (See the exhibit.) Hydrogen is odorless and produces a nearly invisible flame when combusted. It needs just one-tenth of the energy that methane does to ignite, and it can ignite even in very small concentrations when mixed with air. It also dilutes rapidly in air, increasing the risks associated with leakage. Although some of these attributes have advantages, they create safety concerns.

On the operations front, hydrogen’s low calorific value means that larger volumes of it than of natural gas must be transported through gas pipelines to meet the same energy demand, requiring changes to compressors and pressure management systems. The greater volumes of transported gas and the small size of hydrogen molecules create problems for existing metering equipment, too, and increase the risk of leaks. Hydrogen’s ability to embrittle metal pipes is another factor in setting blending limits.

Studies suggest that existing natural gas networks can carry blends that are 20% to 25% hydrogen. But achieving this proportion of hydrogen content is likely to require pipeline operators and their customers to modify or replace equipment. (See the exhibit.) Residential gas appliances today can operate safely with blends of up to 10% hydrogen. But for current appliances to work with blends of 20% hydrogen, their existing burners must be replaced. Managing the replacement process will be both costly and logistically challenging.

Important Decisions Ahead

When the proportion of natural gas in blended mixes falls below specific limits, pipelines typically must either be repurposed to become dedicated pipes for hydrogen or other low-carbon gaseous fuels or be shut down entirely. Although repurposing will be a viable option for many network sections, the economics are likely to be challenging for companies that operate pipelines that serve large areas with dispersed populations, since those circumstances make the cost of investment high in comparison with achievable user revenues.

Economic and operational factors can justify decommissioning pipelines before gas usage reaches zero. Funding decisions, the availability and benefits of alternative technologies, and customers’ climate-related behaviors may change from one neighborhood to the next within the same gas network, making different pipeline sections unfeasible at different times and in different locations.

For example, neighborhoods containing a larger proportion of proactive customers or a relatively high share of house refurbishments may switch more rapidly to heat pumps. We estimate that in neighborhoods where political considerations, climate concerns , and customer behaviors enable faster switching from natural gas, as much as 80% of the existing natural gas distribution network—as well as up to two-thirds of future capex spending if companies invest in the wrong areas—could be at risk of becoming stranded assets.

Actions for Key Players to Take

Given the long-term investment horizons that typify the sector, companies in the midstream gas industry need to think several decades ahead. Gas pipelines can last for 50 years or more, which means that companies face the very real possibility of being encumbered with stranded assets if they don’t make the right choices now and leverage new opportunities from the energy transition. Here are some of the steps that different players must consider.

Pipeline Operators. Pipeline operators should focus on three key topics:

- Planning and Analytical Capabilities. Operators must develop capabilities for forecasting future consumption in different parts of their networks at a far more granular level than they do now. This will help them determine which sections they will likely need to maintain, which they can retrofit to carry hydrogen or CO2, which may need to be retired, and where best to build new hydrogen-carrying pipelines. Each option, even retiring pipelines, will incur a cost, so companies must optimize their investment decisions. They should use these capabilities across strategy, regulatory management, asset management, finance, and customer departments to identify factors that will drive rapid changes in gas usage. Companies that follow best practice are setting up structured decision trees to help them make case-by-case determinations about investments and new connections and are establishing centralized monitoring tools that employ deep analysis to identify crucial tipping points.

- Customer Engagement. Pipeline companies should engage with major gas users and retail businesses to understand the impact that their decarbonization plans will have on pipelines. They should consider different commercial models in which specific large customers partly underwrite volume risks. And they should assess opportunities to proactively transition customers to new fuels, such as hydrogen and biomethane. By working alongside customer groups and policymakers, pipeline operators can help shape the optimal pathway to decarbonization in specific sectors.

- Operating Models. Operators must manage the transition to new operating models for handling different types and volumes of gas across their networks. They will need new asset management and operational capabilities and will have to reset their operating standards. Companies must also roll out hydrogen-ready valves and pipelines, using scheduled refurbishments as an opportunity to replace steel with polyethylene or inner-coated pipes, and adjust their metering infrastructure to measure the volume and quality of the new gases. Finally, they must improve their productivity to prepare for declining natural gas volumes and to avoid escalating unit costs.

Pipeline Business Owners and Investors. The opportunities for expanding into new business areas can differ significantly from one company—and from one network section—to the next, as can the accompanying challenges. Owners and investors in pipeline businesses also face higher risk and investment requirements than in the past. In response to these forces, network companies are adopting a range of responses. Some have moved out of gas distribution, investing instead in electricity. Others have proactively encouraged electrification of areas where natural gas has traditionally dominated. Many companies are experimenting with hydrogen, hydrogen blending, and CO2 technologies. And several players are following a wait-and-see strategy.

We recommend that players keep the energy transition in mind when reviewing their pipeline investments. They should prioritize investments in companies that will benefit from future energy transportation routes (for example, connecting hydrogen supply with demand), that have a robust position in areas with more concentrated customer segments (for example, power or centralized heat generation), and that operate in a supportive regulatory environment (for example, one where regulators have adopted a clear and fair approach to guiding the energy transition and are willing to adjust tariffs to reflect changing volumes, costs, and risks).

Because regulatory periods typically last four to six years in most jurisdictions, a company may not immediately feel the impact of cost and volume challenges. For the same reason, company valuations can be relatively sticky, though all energy companies are under increasing pressure from climate activist shareholders. Nevertheless, business owners and investors should monitor changes in energy usage closely.

Regulators and Policymakers. Regulators will soon face a tough challenge from the changes that the energy transition will bring to midstream pipeline businesses. As operators deal with lower natural gas volumes, higher risk, and increased investment in new or repurposed pipes, customers that continue to use their networks for natural gas could end up paying more. Rising network costs can accelerate the move to alternative fuels: as more and more customers leave the natural gas network, the remaining customers are left with higher bills and so are more likely to exit themselves. (We’ve seen this phenomenon already in the impact of distributed solar power generation on electricity grids.)

Regulators must factor this scenario into their plans to ensure that midstream pipeline companies are properly compensated and remain financially strong in readiness for the energy transition, and to prevent customers from being left behind and exposed to steep price rises if, for example, an alternative technology is not available in their area. To understand the potential impact of regulatory change on demand for both gas and electricity, which are increasingly interlinked, regulators should use more sophisticated modeling and simulation tools. Three topic areas are particularly important:

- Compensation. Regulators should consider an alternative approach to compensating pipeline companies for their costs. Rather than relying on a system that compensates companies for investing after the fact through a regulated return on their asset base, they should weigh the benefits of introducing upfront capital contributions and creating incentives to encourage companies to curb unjustified investments. Finding the optimal compensation mechanism and tariff system will require careful analysis and cooperation between regulators and companies.

- Investments. Regulators should scrutinize operators’ investment plans more closely than in the past to ensure that the plans are fair and effective. The investments needed to make pipeline networks suitable for hydrogen or other low-carbon alternatives must match the likely development of sources of supply and demand. Company plans should aim to minimize the risk of stranded assets and should promote wider decarbonization goals. Fair allocation of investment costs between existing customers and those using the new hydrogen pipeline infrastructure, while avoiding cross-subsidies, will be important, too. Network sections in danger of underutilization may have to be removed from the regulated asset base.

- Directives and Incentives. Blending gases, closing pipelines, and retrofitting or building new pipelines to carry low-carbon fuels will require regulators to set new directives and standards to protect customers and ensure that work is carried out properly. At the same time, policy support for using pipelines to carry low-carbon gases such as hydrogen could simultaneously mitigate pipeline players’ risk of stranded assets and accelerate global decarbonization efforts. Overseeing this transition, setting the right speed and scope, and creating effective incentives for companies are tasks for policymakers. Without incentives from the regulator, operators and investors will resist making decisions to close down pipeline sections for as long as possible to avoid stranded assets. However, a handful of UK companies are now recognizing that possibility in their long-term development plans.

Midstream players need to act now to plan for a net-zero future, with declining natural gas demand and a widespread switch to hydrogen. Although some of the developments outlined above will happen sooner than others, it would be a mistake for companies to dither and postpone making suitable preparations. The energy transition has shown that global shifts away from fossil fuels can happen unexpectedly quickly. And the midstream gas market is likely to be no exception to this rule.