The US desperately needs workers. Workers desperately need help taking care of their children and (increasingly) their parents.

Carina, a 51-year-old nanny in a midwestern suburb, was forced into early retirement in spring 2022 to care for her adult daughter, who had fallen ill. When Carina gave notice, her employer, Sarah, found herself in a similar bind. Unable to find a new nanny in a tight childcare market, Sarah downshifted her promising career running a small health care business to work part-time while her mother watched her children several days per week.

Carina and Sarah each made rational choices that served the best interest of their families. More broadly, their stories exemplify the struggles both paid-care workers (like Carina) and workers with care responsibilities outside their jobs (like Sarah) face. Their stories also foretell a looming crisis across the economy.

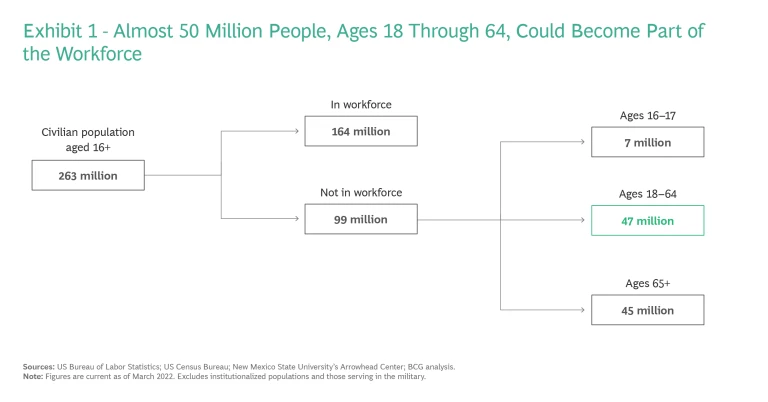

Ongoing labor and talent shortages threaten US economic leadership and future growth. Even as the country approaches a return to prepandemic levels of employment and workforce participation, it faces historic job vacancies: there are 5 million more open jobs than people in the workforce. To address this shortage, US policymakers and employers must act decisively to recruit new workers from the nearly 50 million adults younger than age 65 who don’t hold jobs and to keep current workers working. This will require, among other solutions, reskilling for the jobs of tomorrow , harnessing immigration as a source of talent and innovation, and rethinking retirement.

Another vital antidote to the labor shortage is fixing the care economy, made up of people who provide paid and unpaid care. (See “Overview of the Care Economy.”) Within the care economy, two related and somewhat hidden issues are crucial to the long-term health of the US labor market.

Overview of the Care Economy

- Unpaid Caregivers. Anyone with unpaid-care responsibilities for children, adult family members, or both, whether they themselves are employed.

- Employed Caregivers. A subset of the first group, workers in the broader economy who also have unpaid-care responsibilities, for children, adult family members, or both.

- Paid-Care Workers. Individuals who provide care as their occupation. Many care workers are also employed caregivers with unpaid-care responsibilities. Many of them also rely on paid-care workers for their own family members.

Importantly, we have additionally estimated the value of unpaid caregiving, including that done by employed caregivers outside their formal jobs and by unpaid caregivers such as stay-at-home parents.

First, the US must hire more workers in paid-care jobs in child, adult, and medical (especially chronic) care. These jobs are projected to provide three-quarters of the nation’s job growth between now and 2030. Yet most paid-care jobs are low wage, demanding, and stressful. They are likely to go empty in this labor-constrained market, as evidenced by understaffed daycares and nursing homes nationwide.

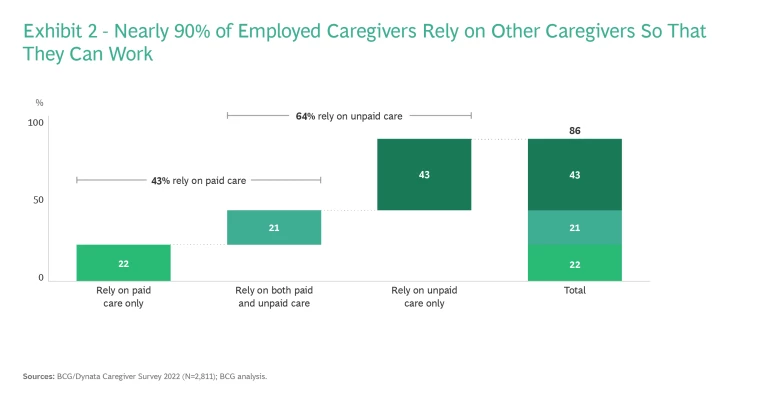

Second, the US must ensure that current workers—women and men, old and young—with unpaid-care responsibilities at home continue to work. These “employed caregivers” (not to be confused with those who work in paid-care jobs) make up more than half of the workforce. Nearly nine in ten employed caregivers like Sarah depend on other care providers—either paid-care workers like Carina or unpaid caregivers like Sarah’s mother—to free them up to perform their own jobs. Paid-care shortages strain the ability of employed caregivers to participate in the workforce, as many have experienced acutely during the pandemic.

Nearly nine in ten employed caregivers depend on other care providers—either paid-care workers or unpaid caregivers—to free them up to perform their own jobs.

While the pandemic laid bare the crisis in the care economy, it was brewing long before COVID-19 and is poised to worsen as the population ages and demand for care increases. Recruiting new paid-care workers and better supporting employed caregivers are critical endeavors. Without a healthy care economy, the workforce falls apart.

The US Needs to Enroll New Workers and Keep Current Ones

Three trends suggest labor shortages will persist for the next decade. First, the share of adults working or looking for work has declined since the late 1990s. Second, US-born population growth is in decline. The US birthrate has dropped steadily the past 15 years, and at 1.6 births per woman is too low for the domestic population to replace itself. Struggling to find satisfactory care or juggle care demands with work, many women are having fewer children or forgoing childbirth altogether. Third, with the recent decline in immigration, foreign-born population growth cannot make up the difference.

There is a silver lining. The US has enough people to close this labor gap. Even with 11 million job vacancies, an all-time high, there are more than four times as many people ages 18 through 64 currently out of the workforce. This is a large pool from which to source new workers. (See Exhibit 1.)

Quality, affordable paid care could encourage and enable more women to work.

Hiring these individuals is critical. Roughly a fifth of these almost 50 million people are unable to work because of disability or health reasons, but more than 4 million want jobs now. As many as 10 million of these potential workers, 90% of them women, are stay-at-home parents or unpaid caregivers tending to adults. The workforce participation rate of women is well below that of men, making women a critical source of new talent. Quality, affordable paid care could encourage and enable more women to work.

More can also be done to retain women. When mothers leave the workforce, it’s often for caregiving reasons. About three-quarters of mothers who quit during the pandemic left to perform care responsibilities at home. Even before COVID-19, women were three times as likely as men to retire early for caregiving reasons. Amid this labor shortage, the US can’t afford to lose these workers. Addressing their care needs is part of the answer.

Caregivers and the Care Economy Are Crucial to the Workforce

With more than half of workers currently caring for children, parents, or other adult family members, employed caregivers are an indispensable part of the workforce. They account for nearly 60% of the US gross domestic product.

In addition to their formal jobs, employed caregivers spend 150 billion hours annually on unpaid-care responsibilities, according to a survey of more than 3,500 workers conducted by BCG and Dynata. Working women are doing this unpaid work more than working men, spending 40% more time on childcare and 20% more on adult care than men.

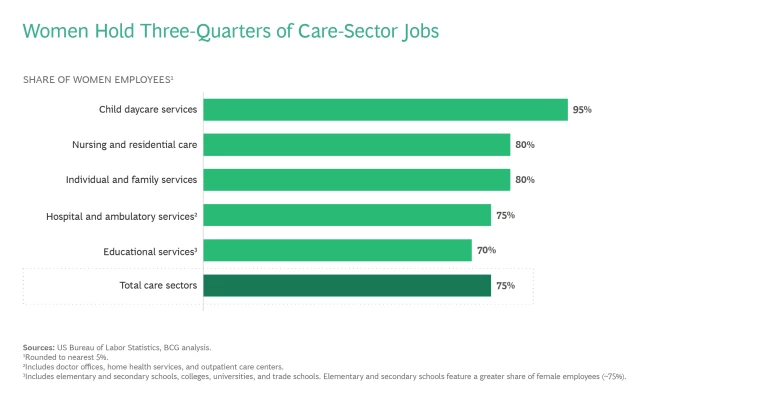

Women are also the heavy lifters in the paid-care economy. About three-quarters of the 34 million people paid to provide care are women. (See “Invest in the Care Economy, Invest in Women.”)

Invest in the Care Economy, Invest in Women

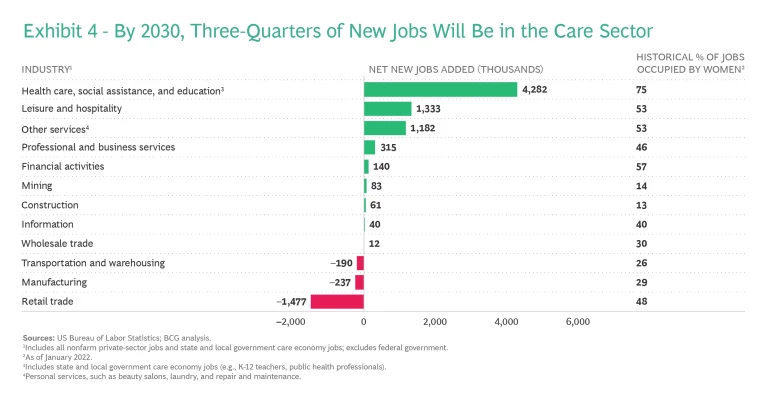

First, improving the pay and working conditions for these employees will most heavily benefit women, who historically make up three-quarters of the care economy workforce. (See the exhibit below.)

Second, strengthening the care economy enables more women to go to work and generate wealth. Even though their participation rate is near a 30-year low, women are more important than ever to the overall labor force. The number of women in the workforce is forecast to grow twice as fast as the number of men: 6% versus 3% by 2030.

Longer term, these investments could also catalyze broader social change and challenge deeply ingrained gender norms around both paid and unpaid caregiving that have held back working women.

Of course, most families rely on a combination of unpaid and paid care. In addition to their own duties after work, 64% rely on unpaid caregivers, such as a stay-at-home spouse or family member, and 43% depend on paid-care workers to go to work. (See Exhibit 2.)

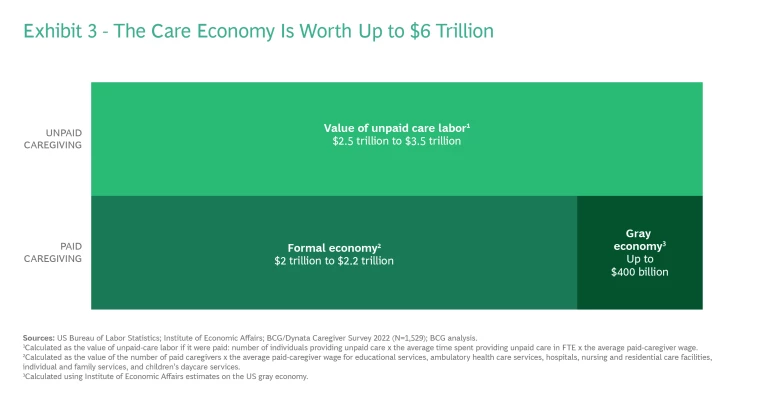

Across all unpaid and paid care, the care economy in the US comprises up to an estimated $6 trillion of activity. (See Exhibit 3.) Over half of this value comes from quantifying unpaid care, which is often overlooked.

The numbers tell only part of the story. The need for care is a human issue, not a political one. Without affordable, quality care to support those who need it, individuals who want to work will never fully reach their potential—and neither will the US economy, especially as care needs grow.

Demand for Adult Care Rises

Surging demand for elder care will change the face of care in the next decade. About 10,000 baby boomers turn 65 every day. By 2034, there will be more people 65 and older than 18 and younger for the first time in US history. As people continue to live longer, the dependency ratio of people 65 and older and under 18 to adults aged 18 through 64 will continue to grow through 2060 and likely beyond.

As boomers age, the share of workers with care responsibilities for adults is projected to increase by 25% in the next decade. Well before elderly adults need nursing, they need help in smaller ways—with transportation, doctor’s appointments, or home chores. Many parents are already simultaneously doing unpaid care for their school-age children and their own aging parents. Members of this growing “sandwich generation”—more than 25% of all caregivers today, according to the BCG and Dynata survey—will likely experience increased stress and burnout, particularly in single-parent households.

The share of workers with care responsibilities for adults is projected to increase by 25% in the next decade.

This soaring demand for care also creates a glaring need for more care jobs. With over 4 million paid-care jobs projected to come online by 2030, filling these care jobs will be critical to addressing an ongoing labor shortage. (See Exhibit 4.)

Filling Paid-Care Jobs Will Be Difficult, Leaving Vacancies

Jobs in the woman-dominated paid-care fields have been historically undervalued. In the nursing- and residential-care sector, for example, two-thirds of jobs are low wage. The average child daycare employee earns $25,000 annually. Home health aides earn only slightly more.

Paying care workers more will not be easy. Parts of the care economy, such as early childcare and elder care, operate on low margins, and others, such as K-12 education and public health, are constrained by tax revenues and policy. For many families, care is already expensive, so there’s not much room to pass the cost of wage increases along to these families.

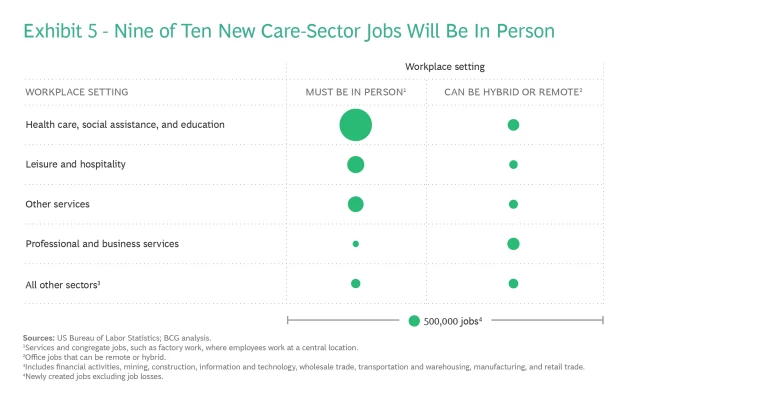

Besides pay, physical presence and emotional demands make these jobs challenging. Remote work is rarely an option. Most of these new care economy jobs will be for positions such as home health aides and chronic-care nurses—high-touch, physically and emotionally taxing jobs. BCG analysis shows that 90% of these new jobs will require a fully in-person presence, compared with about 20% of new professional service jobs. (See Exhibit 5.)

Finally, employees want to feel valued and have boundaries between their work and home lives, something many paid-care workers found lacking during the pandemic. They worked long hours on the frontline, often facing health risks with clients, patients, and students.

Collectively, these factors push care jobs to the tail end of the demand curve. They are at greatest risk of going vacant just when demand for these services is highest. When these jobs go empty, ripple effects reach employed caregivers.

Retaining Employed Caregivers Will Be Challenging

Without a steady inflow of new paid-care workers, employed caregivers seeking to hire them will feel the squeeze. Families are used to stringing together solutions for care when a child is sick, a health aide takes a vacation, or a school is closed. But because care needs do not cease when no worker is there to fill them, chronic shortages in paid care will increase unpaid-care responsibilities.

The good news is that investments in the care economy pay dividends.

Employed caregivers already spend more than 30 hours per week providing unpaid care. At the height of the pandemic, when paid-care shortages became commonplace, employed caregivers were spending an average of 52 hours a week on unpaid-care work , according to BCG research. It’s no wonder that nearly 1 million more employed caregivers than expected left the workforce during the pandemic to perform unpaid-care responsibilities at home.

The good news is that investments in the care economy pay dividends. The Canadian province of Quebec, which instituted subsidized universal daycare in 1997, is a case in point. The share of employed women with children younger than 5 went from 64% to 80%. Today, a greater share of women work in Quebec than the rest of Canada. Meanwhile, Germany increased federal support for daycare in 2005. The daycare participation rates of children under 3 have grown from 37% in 2009 to 64% in 2020. The number of working women and the birth rate have also increased.

A Path Forward: Putting Families at the Center of the Future of Work

A thriving care economy is critical to the long-term health of the US labor market. The whole society must mobilize to revitalize it.

First, to enroll more new workers into paid-care jobs, these jobs need to be more attractive. The private and public sectors must individually and collectively invest in high-quality, accessible, and affordable child and adult care as well as home- and community-based services. The entire sector needs a massive jolt of innovation. It will take significant bipartisan action and public-private partnerships to realize these ambitions.

Second, the US needs to take other measures to ensure that employed caregivers keep working and bring other caregivers into paying jobs. Alongside sensible public policy, companies have a major role to play. Paid leave is at the top of the list. Flexible and stable work hours should also be priorities . Flexible work programs should become permanent, standard policy, not simply a response to the pandemic. Predictable weekly scheduling of hours is long overdue.

Companies could tailor benefits for different employee segments, such as parents with children younger than 5, parents with school-age children, or people caring for elderly and chronically ill persons. They could treat full-time caregiving responsibility as relevant experience for certain jobs to ease caregivers’ paths back into the paid workforce. These investments and practices will help recruit and retain workers in the workforce.

The US is facing a moral and economic quandary involving care and the long-term health of its economy. The pandemic, when families suddenly had to scramble to cover care responsibilities, was a harbinger of what our workforce could look like without investment and innovation in paid care and the care economy overall. These challenges aren’t new, they’re not going away, and they are poised to get worse. In subsequent articles, we will explore the art of the possible in avoiding a prolonged care crisis in the decades ahead.

The authors thank Indra K. Nooyi for inspiring this article and advising us along the way. They thank their colleagues Dan Kahn, Sally Wan, and Ezinne Mong for their contributions to the research and analysis in this article. They also thank the team at Dynata for their collaboration on the survey that made much of this work possible.