Innovative technology and practices are allowing payers and providers to give the elderly what they want most: better care at home.

The trend of aging in place is gaining popularity and credibility around the world. This alternative to living in senior residences revives a traditional way of thinking about elder care, but with an innovative edge. People over age 65 remain in their existing homes or with family, abetted by responsive, flexible, technologically adept home care services. The experiences and outcomes are as good as, or even better than, those of residents in assisted-living facilities or nursing homes—and the costs are lower, too.

Private-sector providers—with support from payers, government regulators and policymakers, referral agencies, and community groups—can serve this population by providing higher-quality services at relatively low cost. They can accomplish this in two ways. The first is with advances in digital and clinical technology : predictive analytics that anticipate health problems, cameras and sensors that monitor patient safety, and telehealth for consultation and other services.

The second way is through

new business models in health care.

The aging-in-place model goes beyond the role of visiting nurses to provide a holistic group of services related to

health care value

, including:

- Clinical services: access to allied health, nurses, primary-care doctors, and specialists, such as for memory care

- Personal care: help with bathing, dressing, and grooming

- Daily-living assistance: meal services, cleaning, gardening, paying bills, and similar support

- Social care: transportation, help with shopping, and providing opportunities to connect with others

For payers, this growing trend represents a viable opportunity to reduce costs while raising customer satisfaction. For providers, it establishes a better business model, where they can charge for comprehensive caregiving that blends different types of services together, rather than managing the constraints of a fee-for-service model, where crossovers are limited. Government regulators and policymakers benefit because of the overall lower costs to public health care systems, the value of preventive care, and the greater overall quality of life. Referral agencies and community groups gain customer and constituent satisfaction.

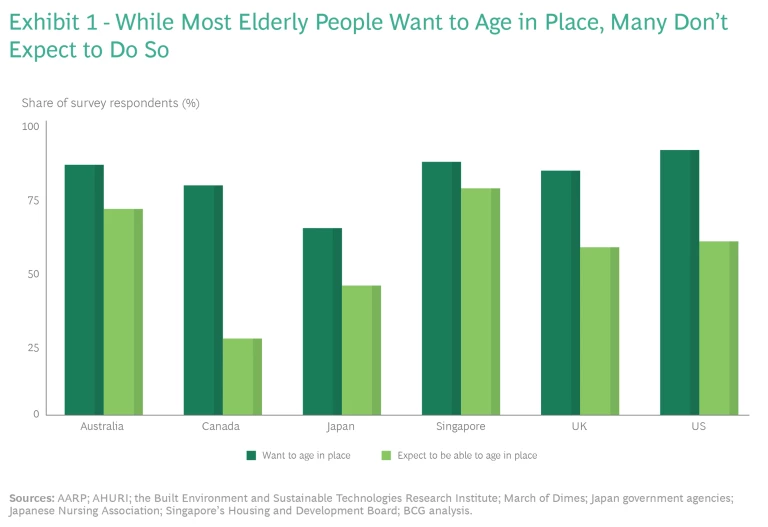

The overwhelming majority of elderly people prefer to remain in their existing home rather than move to a senior residence.

In general, everyone benefits. Aging in place relieves the pressure on institutionalized care. It allows people to remain in their homes and communities, maintain control over their environment, and live more independently than they might otherwise do in a residential care setting. What’s more, doing so helps elderly individuals to preserve close ties with their families and communities. As research on the social determinants of health suggests, this in itself can reduce the risk of disease or vulnerability to injury.

Giving Elderly People What They Want

Researchers around the world have found that the overwhelming majority of elderly people prefer to remain in their existing home rather than move to a senior residence. (See Exhibit 1.) Indeed, recent studies have shown that even when contemplating a future in which they might need regular assistance with dressing, eating, or other daily functions, more than 60% of elderly people say that they would prefer to age in place if they could. But they aren’t sure they’ll be able to.

In many places, the current path of least resistance for elders leads to a dedicated senior residential facility. Before the 1990s, such a move was seen as a last resort; so-called old-age homes were often regarded as inhospitable places with mediocre food and few amenities. But since then, the high end of the senior-living industry has adopted more of a concierge hotel model, revamping some facilities to be cleaner, safer, friendlier, more upscale, and more convenient than they had been. Some facilities are also equipped to house and care for people throughout the aging process, from full independence through all the stages of cognitive and physical decline, with round-the clock skilled nursing support available on the premises. Although such premium residences can be expensive, and so are often financed by the sale of a resident’s home, they have gained wide acceptance.

Nevertheless, some of the challenges and difficulties of senior residential facilities are now coming to light. The COVID-19 pandemic, for example, led to new concentrations of morbidity and mortality among the elderly, and the need to suspend in-person visits caused elderly people to become severely isolated in these environments.

Costs, of course, continue to be an issue, especially for people who have limited resources and may need to support themselves for many years with marginal income. The cost of care in senior living facilities in the United States is, on average, roughly twice the expense of an existing home or apartment, depending on the needs of the individual and the availability of local providers. The overall difference reflects the complex care required for residents of senior facilities, which have nursing staff available at all hours and must meet regulatory requirements for a minimum staff-to-customer ratio.

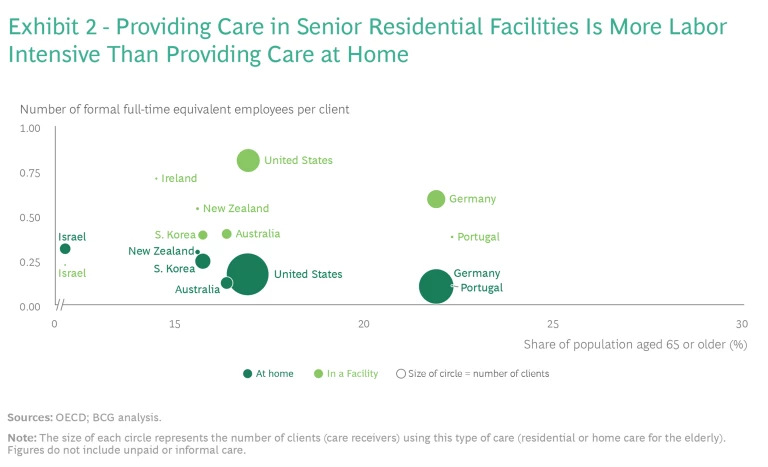

In recent years, aging in place has become an increasingly popular alternative. In contrast with the traditional route, aging in place offers blended care, in which formal staff is mixed with informal labor—the largely unpaid caretaking and housekeeping provided by family, friends, and elderly people themselves. (See Exhibit 2.)

Facing Up to the Trends

If history is any guide, the cost of elder care will almost certainly increase during the next ten years. Since at least the mid-1990s, spending on geriatric care has outpaced overall health spending and GDP growth in OECD countries. This has been driven by increasing investment in therapeutics and clinical practices for aging consumers, the labor costs for skilled workers who must deliver them, and the general ongoing inflation of health care costs, which run at twice the rate of consumer price inflation.

Another critical challenge is the growing need for elder care, driven by demographics and the declining overall health of the population. Currently, even during the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a shortage of facilities for senior residential care, and demand is expected to rise when the pandemic subsides. Many people who are now 65 years old are expected to live into their 90s. From 2020 to 2030, the proportion of the population over age 65 will have grown by 3%—a much greater rate than that of the overall population. And chronic health conditions are prevalent in this population. 85% of the elderly people in the US and 80% of those in Australia are affected; 37% of aging people in Singapore have more than three chronic health issues.

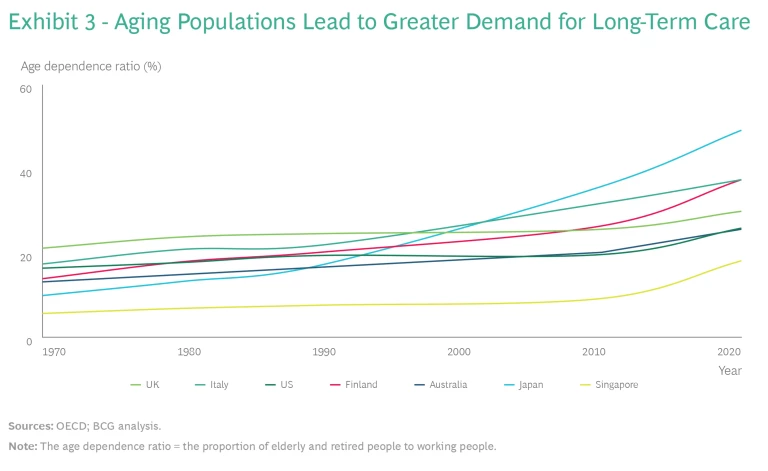

Moreover, as the elderly population continues to grow, the population of taxpayers who support the expense of caring for them continues to shrink in relative terms. Each year, there are fewer workers paying taxes for every aging person who depends on the government safety net; today the global age-dependence ratio stands at 16%, up from 7.7% in 1970 and 9.1% in 1990. A sample of OECD countries, for instance, shows that while some may vary in the rate by which their population ages, all of them are aging. (See Exhibit 3.) By 2029, when the tail end of the US baby boom group reaches age 65, there won’t be enough residential facilities to provide care for everyone who needs them—and many of those facilities are likely to be overcrowded and substandard.

Staffing shortages are also likely to increase. Health and social care workers currently constitute 10% of the total workforce in industrialized countries, but many are leaving the field. They can now find better-paying jobs in less complex and more prestigious working environments.

One way to mitigate the effect of these trends is to support aging in place, which is:

- the preferable choice for most seniors

- less staff intensive

- more diverse and generally innovative

- flexible—when acute care is needed, remote monitoring and other automated technologies are available

For many elderly people, aging in place represents a better experience, at a relatively affordable total cost, than the one offered by the traditional route.

It also makes the most of all the resources in a person’s life. It can complement informal care from family and friends more easily than institutional care, and it fits the demographic, economic, and technological trends of today.

Care in the home won’t be suitable for everyone. But for many elderly people, aging in place represents a better experience, at a relatively affordable total cost, than the one offered by the traditional route. It is estimated that the care needs of half of the global population over age 65—about 3 million people in OECD countries alone—are unmet but could be delivered by better home care services. Because such services involve preventive medicine, they can reduce the need for more expensive, more intensive care later in life. And they can be organized and managed in a more coordinated manner than in the past, avoiding the problems of fragmented care from competing providers.

The biggest hurdle is getting the support structures in place to make it feasible. That’s where governments, businesses, and not-for-profit organizations, which haven’t always been highly supportive in the past, can make a difference.

Five Barriers to Change

Some private-sector firms have enthusiastically stepped into the business of serving those who want to age in place. In Boston, Massachusetts, for example, a not-for-profit organization called the Commonwealth Care Alliance sends nurses, physicians, attendants, and counselors to the homes of about 7,000 elderly people. These individuals, generally 70 years or older, need help at least several times a week. Their care includes assistance with medical issues—such as diabetes, coping with depression, and Alzheimer’s—as well as with daily activities, such as feeding themselves, traveling to the store, and generally managing their lives.

Buurtzorg, a home care agency based in the Netherlands, serves more than 70,000 aging people per year in 24 countries. The 10,000 nurses on its staff work in self-managing teams and are referred to as health coaches. The agency’s care model focuses on listening to clients rather than directing them.

A few governments have also recognized the utility and value of the aging-in-place concept. In Singapore, where the number of people over age 65 is expected to reach 1.4 million (about one-quarter of the total population) by 2030, the government is encouraging most elders to live in their own homes or with family. What’s more, the Singaporean housing development board is investing in R&D for smart sensors and home care robotics, with some commercial enterprises—hospitals, payers, and medical tech firms—participating. These continually evolving technologies are used to monitor the safety of elders at home and help them manage the travails of everyday life.

But in most developed economies, home care services remain relatively underutilized. Although 68% of care recipients (more than 15 million people) receive home-based care in OECD countries, the business of providing that care currently represents less than 30% of the $1.1 trillion market for aged-care services.

Five barriers limit the supply of support.

Inertia in the Referral System. Few business ecosystems have changed as dramatically as that of elder care. Before the 1990s, comparatively few people lived long enough to require a systematic means of handling their needs. When the elderly population boomed, some of the traditional sources of guidance for elders and families—primary care physicians and community services—recognized the value of senior residences and began to make referrals to them. At the time, such facilities were becoming an increasingly acceptable option.

The quality of home-based care has been rising in recent years.

Today, residential care is often treated as the best choice, even as circumstances are changing. Some sources of guidance—including the commercial referral agencies that advertise elder care services—have limited knowledge of recent advances in home care. Their guidance does not always serve seniors well. A 2011 OECD report estimated that in the United States, 48% of the referrals of elderly people to institutional care were inappropriate—either too costly or did not meet their needs. That figure was 36% for the United Kingdom, and 7% for Canada.

Inaccurate Perceptions of the Quality of Home Care. Home care providers are often small organizations with limited oversight, and they vary in capability. For those reasons, home care has had a poor reputation, with mixed levels of acceptance, in the past.

But the quality of home-based care has been rising in recent years. Reviews, observations, and analyses of care quality have found that current outcomes of home-based care are at least equal to, if not better, than those of residential care. One well-accepted measure of quality, for example, is the rate of infections that occur after health interventions. For people aged 65 or over, such infections occur at a rate of 5% to 8% in senior residences, compared with 2.8% elsewhere. As their capabilities grow, home care providers are increasingly interested in advertising their quality of care and providing services to customers with complex needs, such as dementia.

Inherent Challenges in Delivering Home Care. A provider’s ability to deliver quality services systematically is difficult to monitor. Because most providers are small, they partner with other providers to meet the full spectrum of their clients’ needs. Records and observations about an individual’s well-being, therefore, may be fragmented across multiple organizations. What’s more, a customer’s own behavior can be problematic, especially if they are experiencing cognitive decline; they may forbid entry to caregivers, treat them with suspicion, forget to take medication, or ignore self-care. Caregivers can also face challenges with hygiene and clutter, poorly maintained or hazardous homes, and ill-disciplined pets. All of these factors, together, make it difficult for home care providers to offer consistent, reliable service.

The greatest challenge, however, is recruiting and maintaining staff. In three-fourths of OECD countries, demand has outpaced the supply of qualified, experienced caregivers. The resource-intensive, high-touch nature of caregiving, along with fragmented schedules, exacerbates the difficulty.

Home care providers are beginning to address these issues with such digital technologies as remote monitoring, virtual care, predictive analytics, and automated productivity tools for frontline staff. But adoption is still too slow. A 2020 survey of Australian home care providers shows that only 19% employ data analytics, 51% use telehealth solutions, and 58% automatically upload information captured during home care service.

Finally, a more subtle challenge is the ambiguous role of informal caregivers, such as family members and friends, who can make an enormous difference to an older person’s quality of life. But it is not always easy to integrate the activities of informal caregivers with those of a home care provider.

The role of informal caregivers, and how best to make the most of their help, tends to vary by culture. For example, elderly Chinese, Japanese, and South Korean people are more likely to live with their adult children because their cultures ascribe to the Confucian teaching of filial piety. Some countries have even codified this approach into law: the Maintenance of Parents Act in Singapore, for example, entitles older parents to claim financial support from their children. In other countries, such as those in North America, adult children may accept varying levels of responsibility. But informal caregivers exist in every culture and context. Giving them better support and guidance will pay off in more cost-effective, more skilled home care.

Cost of Service. Few countries have come to terms with the immense costs of elder care. A 2020 OECD study of 26 countries concluded that the out-of-pocket costs for a middle-class elderly person could represent up to five times that person’s disposable income, depending on the number of hours of care they need per week.

In some respects, senior residence care is more efficient than home care. Clinicians who visit institutions and group homes see, on average, 20 to 40 patients per day, compared with 5 to 7 when visiting people at home. The cost of home care is even higher in the vast rural areas of Australia and North America, where travel costs and time expended make it hard for providers to break even financially.

In other respects, however, home-based care can be less expensive than senior residence care, especially when labor costs are managed well. Most tasks can be managed by personal-care assistants, who typically earn much less per hour than visiting nurses. Administrative and residential costs are lower as well, especially for long-term homeowners who no longer carry a mortgage. The efforts of informal caregivers and elderly customers themselves, who often prefer to prepare food and participate in their care at home, also help lower costs: the United States has estimated the combined annual economic value of informal care to be about $350 billion. In OECD countries, 55% of the elderly receive only informal home-based care, with no professional assistance at all. A comprehensive, cost-effective, home-based care system could be very welcome in such situations.

Regulation and Reimbursement of Home-Based Care. Developing an oversight regime that motivates caregivers to provide high-quality service at an efficient and affordable price, and meets community expectations of fairness as well, is a complex task. All the challenges of delivering home care, such as fragmented record keeping and inconsistency in staffing, also apply to regulations and reimbursement. An effective approach must take into account the inconsistencies built into home care: the large number of widespread locations and providers, along with the disparate skills and responsibilities of staff members, many of whom work part-time. And the need to schedule visits to an individual’s home also rules out the opportunity for surprise inspections. In addition, payers may worry about fraud, waste, and abuse—such as when providers submit a claim for services that were never delivered.

Many governments rely on providers to regulate themselves or, worse yet, base oversight on consumer complaints and adverse events. This laissez-faire system tends to coexist with very strict coverage constraints, which closely limit the types of services that can be subsidized. The subsidies themselves are typically structured on a fee-for-service basis, which is not ideal. The best schemes are those that reduce fraud through better standards and incentives, subsidize comprehensive full-service support, and focus on paying for value .

A Complement of Comprehensive Solutions

No one solution will address the barriers to adoption of the aging-in-place model because they are interrelated. But a comprehensive package of changes at both the business and the regulatory levels will work well for older customers.

Payers. These organizations should rapidly release protocols and support for home care providers:

- Delineate a menu of reimbursable services, which may differ from those provided in senior residences.

- Support preventive care, digital monitors, and training for staff and informal caregivers, which may decrease overall costs in the long run.

- Develop shared reporting and technology platforms, providing scale and convenience for information, claims, and reimbursement activity.

- Support consumer choice and convenience through comprehensive, easy-to-navigate online user interfaces, and include insights into what typically works for consumers like them.

Providers. These organizations should invest in innovative approaches that put customers first:

- Create a value-based package of services tailored to customer needs, including preventive care, early monitoring of symptoms, practical guidance, and social and emotional support.

- Form partnerships with specialized health care providers and hospitals for integrated care, clinical governance, and consumer-focused referrals.

- Invest in improving the abilities of the company’s workforce, ideally with the support of other stakeholders, such as payers and government. An optimal frontline workforce comprises people with a range of qualifications, skills (including leadership), and qualities of emotional intelligence (including compassion, commitment, and resourcefulness).

- Manage staffing shortages by adopting methods that have helped other businesses, such as hotels and clinics, address them. These include more flexible and part-time working arrangements, incentives for quality, and training in complementary skills.

- Give staff more autonomy and accountability, so they can respond quickly to customer needs. In Buurtzorg, for example, case managers in self-managing teams make all the necessary decisions. This also has great value in recruiting and retaining staff.

- Take advantage of digital technology, again with the support of payers and governments if possible. In Singapore, sensors and devices collect data about the daily living patterns of elderly people—such as what time they typically wake up in the morning or leave their home. When the data has been aggregated and analyzed, a platform can suggest improvements in overall care or alert designated family members if there is an accident. Sensor-enabled medication dispensers are being tested now; they can track when individuals don’t take their prescriptions and remind them to do so.

Government Regulators and Policymakers. These public-sector entities should redesign their systems to meet the unique needs of home-based care, complementing or adapting existing rules to the new realities. Among the individual measures that may apply in particular locations:

- Help cut the unnecessary red tape that constrains providers from offering new models of care. Look to simplify administrative processes, such as reporting systems, claims standards, and worker accreditation registries.

- Set new regulatory frameworks that provide better support to help the ecosystems of payers and home care providers work together—for example, in sharing information, setting standards, and maintaining quality control. Calibrate these frameworks for the unique attributes of home-based care and for the opportunities inherent in digital technology.

- Ensure the development of a higher-quality, more compassionate home care workforce by following best practices in professional training, licensing, and accreditation for a broader range of skills. Establish and enforce high standards for professional care. Establish a system of ongoing monitoring for quality. Develop public-sector support for upskilling and training home care employees, especially in areas related to care coordination. In 2018, for example, the Norwegian government funded a project to improve nurses’ skills in communicating with formal and informal caregivers. And the German government trains nurses in case management, communication with other professionals, conflict management, collaboration, and care oversight, which includes ongoing evaluations of the quality of care and the resulting health and well-being of the patients.

- Further support the attraction and retention of the workforce through incentives, benefits, and opportunities. Specific measures might include immigration rules that favor people with health care aptitude and the willingness to work in personal care, along with incentives for quality.

Referral Agencies and Community Groups.

These organizations, which include for-profit and not-for-profit entities, provide information and guidance to elderly people. They help people navigate through the range of options for senior living, and they make referrals to residential and home care services. Their engagement would be extremely valuable and could include the following measures:

- Support home care as an option, feature it more prominently in the menu of options offered, and find ways to be compensated for this if necessary.

- Explore more comprehensive approaches to referrals and marketing. In Austria, for instance, referral services act as brokers and advocates for the elderly, helping them to navigate government services.

- Strengthen connections with health care professionals, psychologists, social workers, family members, and community volunteers. People who spend a great deal of time with the elderly can spot early indications of decline and so may be in a good position to provide referrals and guidance at the right time.

The Entire Industry. Payers, providers, referral agencies, and community groups—ideally, with the support of government regulators and policymakers and the elderly themselves—should collaborate on several areas:

- Develop and support a value-based payer reimbursement model that

would favor payments for bundled services over fee-for-service or day rates and provide incentives for higher-quality care. Take into account the savings that payers and governments would gain because of costs that would be lower than those associated with senior residences. For example, in the US, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation extend supplementary benefits to include nonskilled home care services, such as enhanced benefits for food, companionship, and other services related to social determinants of health. This encourages the development of comprehensive care solutions in the home.

- Build a talent pipeline at scale, continuously recruiting people who have the caliber and compassion needed to care for older people. Support measures, such as flexible and part-time work models, that enable people to work in this field who otherwise could not be available.

- Provide better training and support for informal caregivers, who don’t always have the skills needed for the job. Set up interactive learning and groups so that caregivers can benefit from one another’s experience.

- Work together across organizational boundaries to collect and analyze data related to provider quality and consumer outcomes, including standards for safeguarding privacy. This use of data will raise awareness of value and quality. Providers and others can use predictive analytics to continually improve their services and refine the model of home health care.

- Bring policies and practices into harmony with adjacent health and social care systems. For example, make it easier for one provider to handle all the issues related to aging and disability. Design the system so that it covers the full consumer journey, without awkward handoffs, such as the gap between hospital stays and home rehabilitation care. For example, Japan has created a new role, called long-term care managers, who are licensed to coordinate the provision of health care and social services for elderly individuals.

Aging in place could transform health care for the elderly around the world. Together, the stakeholders—payers, providers, government regulators and policymakers, and referral agencies and community groups—have a choice. They can leave old practices in place and bear the extra long-term financial and human costs. Or they can pay attention to the trends in cost, demographics, and labor and change their ways of working. That’s the change that consumers—who are better informed, with ever-higher expectations of convenience, quality, and price—want.

These issues are personal. None of us is getting any younger, and many will turn to this visionary, realistic way to achieve superior care in our existing homes. If we can make it work for others, we will benefit directly ourselves.

The authors would like to thank Allison Blake, Priya Chandran, Jennifer Clawson, and Josh Hilton for their assistance in the development of this article.