Multilevel resilience is built upon the relationship between organizational and personal resilience, an optimal level of stress, and the right approach to change.

As a result of the COVID crisis, the word “resilience” has made a resurgence in the business vocabulary. The term is usually used in two different contexts: organizational resilience, which refers to an organization’s ability to recover and thrive after a shock, and personal resilience, which refers to an individual’s capacity to do the same.

For the most part, organizational and personal resilience have been studied and discussed separately. Consequently, their interdependence is not widely understood, let alone operationalized. As organizations attempt to rebuild after COVID to both capitalize on new opportunities and build in resilience to future shocks, it’s worth reflecting on the relationship between these two aspects of resilience.

The Science of Multilevel Resilience

The interplay between personal and organizational resilience is fundamental to understanding how organizations can deal with stressors. In complex, multilevel systems, exposure to adversity (or opportunity) at lower levels of a system can lead to resilience at higher levels, though this is not guaranteed.

The potential conflicts between levels are minimized when the primary level of selection is that of the whole system, and this explains why our personal resilience depends to a large extent on the resilience of our tissues and organs. Consider, for example, the muscular system in the human body. When muscle fibers are pushed beyond their current capability—exposed to adversity through physical effort—muscle fibers tear apart. These microtears help muscles to reform, recover, and grow back stronger.

Muscles aren’t the only part of the body that exhibits such multilevel effects: the same dynamic can be found in the adaptive immune system. In response to infection in individual cells, white blood cells known as lymphocytes create antibodies to fight the invader, and the antibodies are thereafter distributed throughout the entire body. As a result, the entire immune system becomes more resilient; the next time it is exposed to a pathogen, it can fight off the invader without causing a more serious and dangerous infection.

Organizations can put mechanisms in place so that personal resilience and organizational resilience are not in conflict.

Many social systems are characterized by the same dynamic, with one key difference. When adversity occurs, humans are better able to draw deeper lessons from their experiences. Humans are able to reflect, analyze, adapt, hypothesize, and imagine different scenarios. This means that humans have an even richer capacity to grow and benefit from adversity—becoming more adaptive, imaginative, and resourceful through experimenting, reflecting, and taking action in response to disruption. In our societies, this may or may not be beneficial to the society as a whole, and indeed it can lead to growing inequity when some members are able to take greater advantage of changing conditions. But organizations are different; they can put mechanisms in place so that personal resilience and organizational resilience are not in conflict as they work to achieve resilience of the organization as a whole.

The importance of exposure to adversity and the relationship between personal resilience and organizational resilience is well understood in the military. When surveyed on the leadership strategies and practices used to overcome adversity, 100% of military leaders stated that for a military unit to overcome adversity in combat, the commander must build resilience in service personnel prior to combat deployment. To do so, said 87% of the leaders, requires the design of realistic training that creates adversity.

Multiple Timescales of Resilience

Another important aspect of resilience, necessary to understand the relationship between personal and organizational resilience, is that it plays out over several timescales.

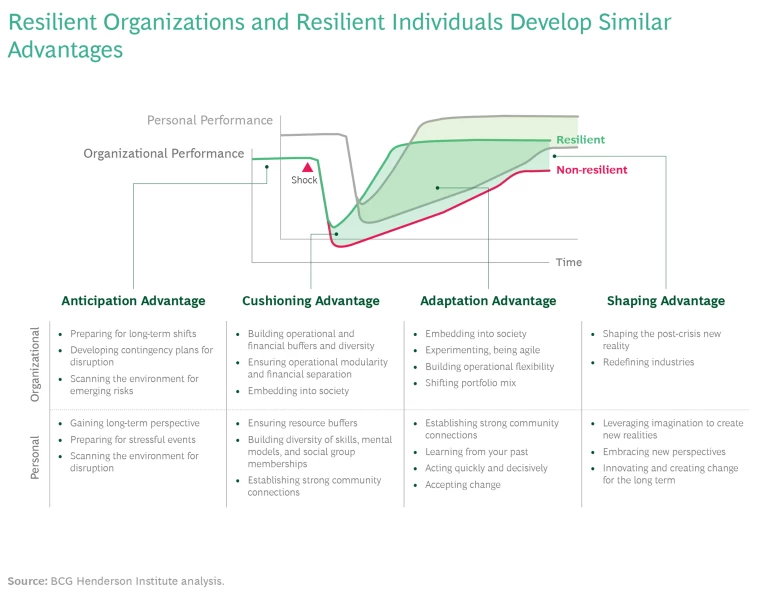

We previously explored how biological systems display characteristics of resilience on multiple timescales, and how business can learn from such systems. Organizational resilience refers to a company’s capacity to absorb stress, recover critical functionality, and thrive in altered circumstances after a crisis. In our previous research, we described how resilient organizations develop four advantages over multiple timescales that enable them to outperform their competitors after a crisis:

- Anticipation advantage: the ability to recognize potential threats and prepare for them in advance

- Cushioning advantage: the ability to withstand the initial shock

- Adaptation advantage: the ability to quickly identify the actions needed to restore operations and implement them swiftly

- Shaping advantage: the ability to shape and exploit the dynamics of the industry in the post-shock environment

Resilient individuals develop similar advantages over multiple timescales. This means that personal resilience is more than just grit and determination. Personal resilience is the process by which an individual anticipates, cushions, and adapts to disruptions, and shapes their environment in ways that improve their mental and physical homeostasis and effectiveness.

A Mutually Reinforcing Relationship

When these principles are applied to organizations, the result is a multilevel, multi-timescale model encompassing organizational and personal resilience. (See the exhibit.)

The two levels of resilience are mutually reinforcing; each depends on and reinforces the other, and each is less effective absent the other.

Organizational resilience depends on personal resilience. Individuals who are personally resilient can deploy their prudence, proactiveness, and long-term orientation to help the organization prepare for long-term shifts and risks, building anticipation advantage. Individuals who are personally resilient can deploy their diversity of mental models and skills, risk tolerance tactics, and community support to help the organization build redundancy, diversity, and modularity, as well as embed itself in society, building cushioning advantage. Individuals who are personally resilient can deploy their community support, resourcefulness, problem-solving skills, and adaptation skills to help the organization experiment with new options, building adaptation advantage. And finally, individuals who are personally resilient can deploy their imagination and innovation skills to help the organization redefine its industry for the future, building shaping advantage.

Meanwhile, organizational resilience creates a context that supports building the four advantages of personal resilience. Organizations with anticipation advantage that emphasize a long-term context help employees develop prudence, proactiveness, and a long-term orientation. Organizations that build a cushioning advantage by focusing on building redundancy, diversity, modularity, and embeddedness emphasize the importance of diversity of mental models and skills, risk tolerance, and community support. Organizations that build adaptation advantage by quickly adapting to change emphasize the importance of community support, resourcefulness, problem-solving skills, and adaptation skills. And organizations that build shaping advantage by viewing crises as opportunities for growth—not merely challenges—emphasize the importance of imagination and innovation skills.

The Optimal Level and Approach to Stress

In order to develop personal resilience, employees must experience and overcome adversity or change. Yet the adversity or change can’t be so overwhelming that it leads to breakdown instead of learning and growth. Therefore, personal resilience is best developed in an environment with the optimal level of stress.

However, some organizations operate under the assumption that stress is always negative and that leaders should protect their employees from stress at work. This tendency is also evident in business research; many recent articles in leading managerial publications emphasize the need to protect employees and minimize work stress. Some even posit that one of the main roles of a leader is to shield their followers and subordinates from stress, maintaining calmness and stability throughout difficult times.

Too much stress in the workplace can certainly be harmful. But if we attempt to minimize or eliminate stress, we could miss out on all the benefits described above. Building personal resilience is not about protecting individuals from stress—it’s about finding the level of stress that can lead to personal growth.

If we attempt to minimize or eliminate workplace stress, we could miss out on many benefits.

Stress often results from change, so the approach to change is critical in building resilience. Organizations and employees that attempt to minimize internal change may find this effective for small to moderate environmental change but disastrous for significant environmental change. Take ocean habitats as an example. Coral reefs are formed by huge colonies of corals that secrete hard calcareous exoskeletons, giving them structural rigidity. This approach is largely effective for corals, which face mild environments that change only moderately and infrequently. Yet the same approach would not work for kelp forests, because the environment of kelp is prone to strong wind, waves, and currents. Kelp can recover from harsh conditions because it is not rigid; its blades can flex or detach and regrow. Its flexibility reduces drag as water velocity increases, preventing tears from strong ocean waves.

Like coral, organizations and employees that practice only buffering or containment of change may survive moderate environmental change but break down in extreme conditions. This is especially important at the organizational level, where too much resistance eventually leads into the need for major change and risky, large-scale transformation efforts. Instead, an approach that emphasizes flexibility, evolvability, and environmental shaping is more effective for long-term sustainability. For example, Alibaba’s organizational philosophy is predicated on change, and it deliberately hires change-tolerant or change-seeking individuals and ensures that all of its internal systems are designed for evolvability in the face of changing conditions.

How Leaders Can Build Resilience at Multiple Levels

Multilevel resilience is built upon the relationship between organizational and personal resilience, an optimal level of stress, and the right approach to change. Leaders can take a number of actions to build such a resilient organizational system.

Emphasize the role of the individual in organizational resilience. An organization’s performance after a crisis depends not only on collective operations and strategy but also on its individual people. In internal and external communications, emphasize the value of individual influence in the organization’s performance, and help each employee understand how their individual role helps to drive the success of the business during a crisis.

Develop a culture that encourages change and welcomes experimentation, failure, and learning. Everyone across the organization must understand that adversity and change are necessary components of growth. Create shared values, goals, and practices that encourage learning through both successful and unsuccessful endeavors. Such a culture can provide growth opportunities for existing employees and assist in attracting individuals who value change and growth to further reinforce the new culture.

Invest in individuals who demonstrate personal resilience. Employees who are personally resilient develop attitudes and skills that are well suited to dynamic environments that require stressful situations to be framed in optimistic terms. Those who demonstrate resilience should be selected for, rewarded, and promoted to positions of influence, where they can serve as role models for other employees. For instance, among the key reforms carried out by General Dempsey in creating resilience in the face of new military threats were deliberately increasing the failure rates for elite training courses and selecting for individuals who were able to bounce back from adversity and failure.

Find the right balance of adversity and stability. Too little adversity takes away the opportunity for employees to develop dynamic skills. Too much adversity, like a muscle that is overstrained to the point of injury, delays recovery and growth. Instead, leaders should create expandable responsibilities—in the form of more, harder, or different tasks—that scale in proportion to the capabilities and confidence of employees. Another important tactic is to eliminate the unproductive stress and frustration that is created by the organization itself, through excessive complexity or bureaucracy. The optimal levels of adversity and stress stretch individuals just beyond their current capabilities and skills.

Balance change and reflection. A recovery period isn’t a nice-to-have, it’s a fundamental part of building strength. The recovery of a muscle begins only when it is no longer strained—continuous strain leads to injury and prevents growth. Similarly, if individuals are constantly under stress, they will not be able to recover and will eventually burn out. Instead, allow for periods without adversity to support recovery, reflection, and learning. This can be done through encouraging reflection, creating rotations between active and reflective roles, ensuring individuals maintain balanced portfolios of activities, and allowing for sabbaticals, for example.

Build the individual capabilities that drive personal resilience. Like a body that provides nutrients and blood to grow muscles, organizations must provide the right mental, physical, and social resources to aid growth and learning. For instance, this can come in the form of mental health services, resilience training, experience-based learning, job flexibility, and community support.

Organizational resilience and personal resilience are rarely considered together. Yet taking a multilevel, multi-timescale approach—one that builds a positive feedback loop that facilitates mutually reinforcing resilience between organizations and employees—opens new possibilities on both levels.