The World Health Organization estimates that the global shortage in the health care workforce will reach about 15 million by 2030. Many doctors, nurses, and other health care workers are burnt out. Others are approaching retirement. But demand for health services remains high. And while the pandemic did not create these problems, it did exacerbate them.

There is no easy solution. Traditional approaches to workforce shortages focus on increasing the size of the pipeline by persuading more people to enter a particular profession. That's necessary but not sufficient. Too many people are leaving positions in health care prematurely, creating a revolving door of arrivals and departures. In many countries, especially the US, care is inefficient, requiring more people and more drudgery than necessary.

To not just attract but also retain employees, health care needs to become more purposeful. Purpose is a magnet that draws people to a field and keeps them there. Most people choose jobs in health and medicine to do good. But along the way, long hours, constant pressure, and busy work tend to disconnect employees from the values that drew them to their professions in the first place. Burnout among physicians has reached 38%, compared with 28% for the general population, and it's even higher for frontline practitioners in family, internal, and emergency

Providers also need to manage demand by making the machinery of health care more productive and less bureaucratic. There needs to be more direct care and more experimentation with operating models that do not merely increase the size of the health care workforce.

The workforce crisis in health care demands both short- and long-term solutions. Many of the long-term solutions, such as innovative models of care, are structural and will require multiyear efforts. Enhancing purpose and productivity should serve as guideposts along the way toward a resolution to the current crisis and the creation of a new health care operating model.

The Crisis Is Real

“If I had a mandate to define the priorities for the OECD ministers of health, at the top of my list, especially in light of the coronavirus pandemic, would be addressing health care’s growing people crisis,” said Francesca Colombo, head of the OECD's health

Workforce shortages have real-world consequences in patient outcomes. Nursing shortages increase the frequency of medication errors, which, according to the National Library of Medicine, can increase hospital stays by an average of two days. Meanwhile, a 10% increase in the number of nurses is associated with nine fewer deaths per 1,000 patients, the Journal of Nursing Administration reports.

Shortages also have real-world economic consequences. Shaving a year off residents' life expectancy lowers a country's per capita GDP by 4%. Between 2019 and 2021, average US life expectancy dropped by three years, from 79 to 76, the sharpest pandemic decline among wealthy countries, many of which showed improvements in 2021.

Who's Leaving Health Care and Why

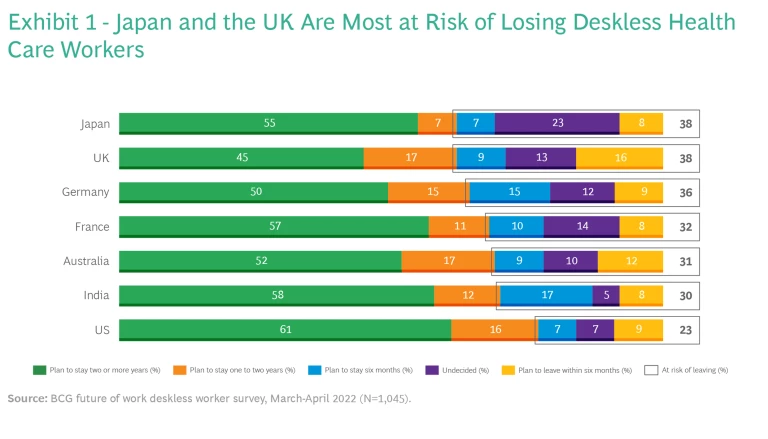

We recently surveyed more than 1,000 “deskless” health care workers in seven countries. These workers need to be physically present to perform many of the jobs that health care requires. A third of them are at some risk of leaving their jobs in the next six months, the survey found, with those in Japan and the UK most likely to do so and those in the US least likely. (See Exhibit 1.)

The younger the employee, the more open he or she is to leaving. Half of Gen Z employees in health care are at risk of leaving their jobs in the next six months, compared with less than a third of Gen X employees and less than a fifth of baby boomers.

Deskless health care workers are contemplating leaving for reasons not necessarily related to the pandemic. The two most common are career advancement (49%) and pay (43%), both of which predate the pandemic as factors. Flexibility (26%) and work-life balance (24%) were cited far less often, despite their relevance in a post-pandemic world.

Every health care workforce shortage is unique. Different nations have different types of productivity challenges. The National Health Service in the UK, for example, has more employees than at the start of the pandemic but is performing fewer procedures, and Australia saw a 2% increase in general practitioners that coincided with a 21% decrease in appointments between December 2019 and December 2021. Other countries face shortages stemming from global labor patterns. India, for example, is struggling with a nursing shortage despite being a leading exporter of nurses to other countries. Socioeconomic factors are also at work. In the US, medical school debt pushes many new doctors into higher-paying jobs and away from rural and remote regions with the greatest health care needs.

Diagnosis at the Local Level

Health care and health care delivery are ultimately local in nature. While the shortage may require long-term changes in national policy, individual health care systems need to understand the size and nature of shortages in their local markets. They should be breaking down overall trends and averages to understand why people leave certain jobs and why some jobs are particularly hard to fill. Health system leaders should also understand whether personnel in roles experiencing a surplus of employee capacity can be retrained to fill other roles.

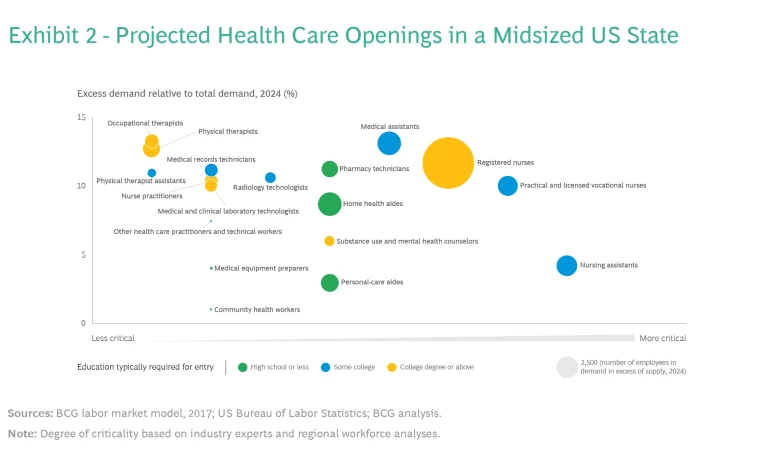

Before the pandemic, we projected the health care workforce needs of a midsized US state in 2024. Analysis of qualitative and quantitative data allowed us to identify not just which jobs had the most openings but where the mismatch between supply and demand was greatest. In this one state, the largest number of openings was for registered nurses, but the need for medical assistants, who do not require a four-year college degree, would in the future be more critical, according to experts. (See Exhibit 2.)

This type of detailed analysis can help leaders address specific shortages in specific places with a targeted plan. By answering questions about a given workforce, including its size, retention rate, and the attitudes of employees, organizations can design and execute more effective solutions.

From Diagnosis to Action

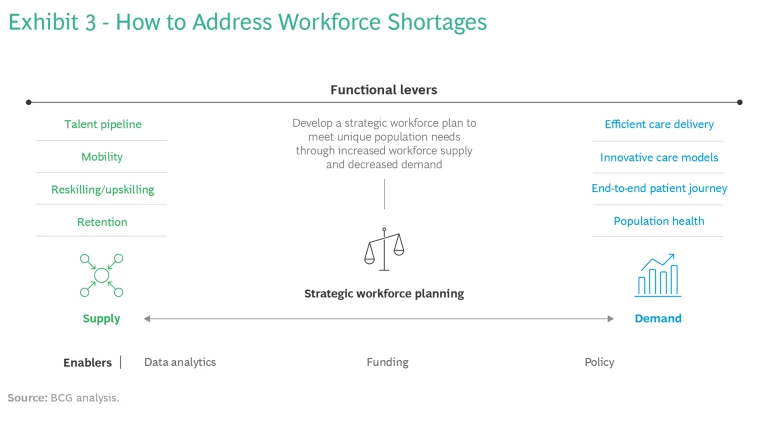

Fundamentally, all workforce shortages stem from an imbalance between supply and demand. Any solution must therefore provide a mix of tools aimed at managing supply and reshaping demand. (See Exhibit 3.)

Managing Supply By Enhancing Purpose

A common denominator across many successful initiatives, including those described below, is that employees are not just offered higher pay. Rather, the health care system tries to understand and address employees' frustrations and restore their dedication to helping others by offering training, mentoring, and career opportunities. In other words, they try to make work more purposeful. Recruits want to join organizations that have a passionate and engaged workforce. And existing employees are more likely to remain in such jobs.

Four primary factors influence the supply of available health care workers. Interestingly, many providers have discovered that improvement in one dimension often has positive spillover effects in other areas.

Retention. Amedisys, a health care system based in Louisiana, was able to lower voluntary turnover by 20% by combining traditional approaches to hiring and retention—such as onboarding interviews, quarterly pulse surveys, and exit interviews—with new, data-driven techniques. Detailed analysis of the resulting data uncovered 36 factors that could trigger voluntary departures. This type of predictive analysis has the potential to address such retention risks as early retirement and to sharpen the employee value proposition, which can help in recruiting.

Meanwhile, HCA Healthcare, which operates more than 180 hospitals in the US and UK, is addressing nurse burnout by providing real-time assistance from psychologists and social workers. It also offers a mobile app that allows nurses to connect with mentors and network with peers.

A common denominator across many successful initiatives is that employees are not just offered higher pay.

Talent Pipeline. Partnerships between institutions of higher education and employers can power the talent pipeline. West Michigan’s Grand Valley State University and Corewell Health (formerly Beaumont Health Spectrum Health) partnered to expand the number of Grand Valley nursing graduates from 1,000 to 1,500 a year through increased financial aid, curriculum enhancements, student support services, and clinical experiences. Corewell hopes the $19 million initiative will reduce its workforce gaps by improving access to local jobs and training in the medical field.

Mobility. Rather than rely on static or outdated views of staffing levels, organizations can allocate personnel to areas of greatest need. Baystate Health, which operates in western Massachusetts, created a team of professionals in anesthesia, radiology and imaging, emergency medicine, and other disciplines that it dispatches to one of four hospitals depending on need. A set of common protocols allows the practitioners to maintain the quality of care as they move from hospital to hospital.

Reskilling and Upskilling. Training and education allow an organization to develop talent within its own workforce rather than hiring from outside. LHC Group, a provider of home health services in the US, invested $20 million in the College of Nursing and Allied Health Professions at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. The arrangement allows LHC to provide employees with discounted tuition and nurses with career progression opportunities as adjunct professors or through postgraduate training programs.

Reshaping Demand by Improving Productivity

Barring another pandemic or some other health care crisis, demand for health care is likely to remain fairly constant in the coming years. Providers can meet that demand with greater efficiency, innovation, and sophistication in the short to medium term, while working to improve the overall health of the population in the long term.

The first three initiatives described below have improved the productivity of the health care systems that undertook them, while the fourth is contributing to a healthier society. In all cases, greater productivity is reducing the need for medical care and services.

Efficient Care Delivery. The pandemic set in motion innovations in self-care, remote care, and delivery. Telemedicine and remote patient monitoring have both been around for a while but have not yet reached their full potential. BCG estimates that at least $1.6 trillion can be saved globally each year through virtual consultations and other digital services .

As part of a larger effort to eliminate defects in care, University Hospitals in Cleveland focused on discharging acutely ill patients to their homes rather than to skilled-nursing facilities. Before discharge, the hospitals schedule a follow-up visit with a primary-care or specialist physician within seven days. After one year, 61% of patients were receiving these visits, up from 25%. Readmission rates within 90 days of discharge fell from 32% to 27%.

Innovative Care Models. In the future, health care delivery is likely to be faster, cheaper, and closer to home. More than 40% of industry leaders anticipate an increase in procedures performed in outpatient ambulatory settings, and more than 60% expect to see more care delivered in nonclinical settings such as the home. We project that as much as one-third of all hospital volume could move into ambulatory, home, and virtual-visit settings over the next ten years. Solutions are already expanding to cover more points of care—including diagnostics, urgent care, primary care, specialty care, and postacute care. The merger of Teladoc and Livongo in 2020 is one example of the convergence of telemedicine and remote patient monitoring in a single company.

End-to-End Patient Journey. Every stage in the patient journey—from provider selection through posthospitalization—can be reshaped and improved through personalization. Personalized health care recognizes patients as unique individuals with unique health histories and circumstances. It aims to achieve better health outcomes by providing a tailored approach to care and a hassle-free experience.

Providers can meet the demand with greater efficiency, innovation, and sophistication, while working to improve the overall health of the population.

In just 6 to 12 months, some payers that have implemented personalization have seen the patient experience improve by 10%, administrative costs drop by 5% to 10%, and quality increase by 20% to 25%. Similarly, providers have seen significant improvements in consumer satisfaction, in the length of hospital stays, and in 30-day readmissions.

The UK's Royal Marsden, for example, coordinated cancer services through the London Cancer Hub during the pandemic. Despite an overall decrease in cancer referrals and the potential for increased cancer-related deaths, the Cancer Hub ensured continuity of care by sharing resources and staff across ten hospitals.

Population Health. Oak Street Health, a US health care provider focusing on the elderly in underserved neighborhoods, aims to keep patients out of acute-care settings through preventive and public-health measures . The organization places clinics in areas with high foot traffic, provides transportation to patients who cannot travel on their own, and urges primary-care doctors and nurses invest time in getting to know their patients. Oak Street identifies potential risks by segmenting patients into one of four tiers based on age, comorbidities, recent utilization patterns, and degree of social support. This helps target interventions and allocate resources to maintain patient health. Oak Street reports that the approach has helped to halve hospital and emergency room admissions and to lower readmission rates by almost as much.

The health care workforce crisis is real. Money is not the only answer. Many health care organizations are still able to recruit, but they struggle to retain employees. Health care organizations can heal rather than bandage their current operating model by letting productivity and purpose be their guides.

In undergoing this work, leaders should consider the following questions as prods to action:

- How will your organization harness purpose to address workforce challenges?

- What are the most effective levers with which your organization can address its workforce challenges?

- What are the partnerships your organization can establish to invigorate workforce supply?

- How big an operational and workforce benefit can your organization gain by pivoting from stopgaps, such as hiring traveling nurses, to long-term, systemic solutions?

- How can your organization ensure enduring workforce stability through targeted investments in training, retention, and efficiency?