Everywhere we look, we see companies making commitments to climate and sustainability goals. But while the bold net-zero pledges that CEOs, investors, and boards are making have received a positive response, it’s clear that companies still have a long way to go to inspire the consumer action needed to help reach our global climate ambitions.

What will it take to make consumers choose environmental sustainability, whether through their behaviors or their purchases? What are C-suite executives (CXOs) missing?

We believe the answers lie with consumers themselves. Our research has confirmed that consumers do care about climate and sustainability and want to do their part. (See the sidebar “About Our Research.”)

About Our Research

We assessed 14 product and service categories:

- Consumer packaged goods, specifically beverages, snacks, skin care, and home care

- Retail, specifically grocery retail (supermarkets and convenience stores) and dining (restaurants)

- Leisure travel (airlines, trains, auto, and public transport)

- Apparel (clothing)

- Streaming media services (music and video)

- Electronic devices (PCs and tablets)

- Building materials (paint, wiring, flooring, and tiles)

- Luxury products (clothing, accessories, jewelry, and watches)

- Electric utilities (power supply; surveyed in France, Germany, Italy, and the US only)

- Cars (fossil fuel, electric, or hybrid powered)

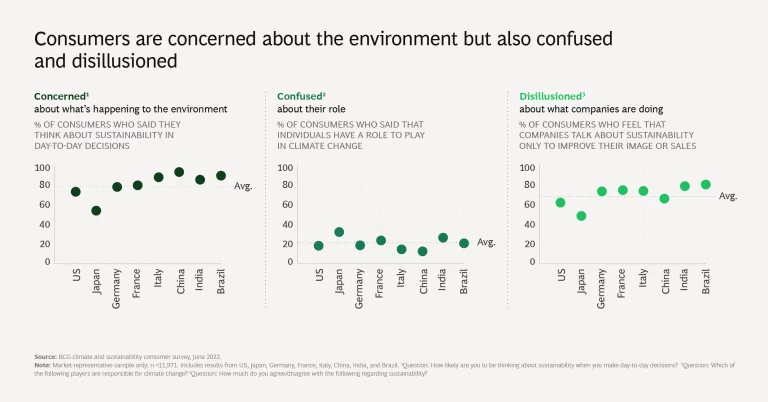

But some consumers are confused about what they, as individuals, can do to make a difference; only 20% think that they can personally have an impact. More significantly, approximately 70% are disillusioned—wary of corporate claims about progress toward sustainability and suspicious that those corporate commitments are a ruse masking the true intent: merely to burnish reputations and attract customers. High-profile allegations of corporate greenwashing only bolster the disillusionment.

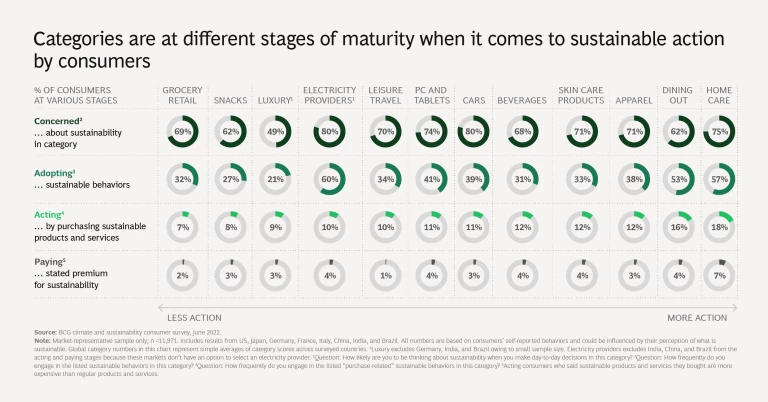

While up to 80% of consumers say they think about sustainability in their day-to-day purchases, only 1% to 7% report that they are paying a premium for sustainable products and services. Leaders often interpret this extremely broad “say-do” gap as a signal that consumers are not yet ready to follow through on their own convictions about sustainability. We believe, however, that measuring only those two extremes conveys an incomplete picture of the true range of actual consumer behaviors.

We examined every stage of consumer behavior in our research and identified two other important groups of consumers who are on the threshold of embracing sustainable products and services. The key question for CXOs is, How do we encourage more of those consumers to cross that threshold and make sustainable choices?

Breaking Down the “Say-Do” Gap

Between the consumers who are paying a premium for sustainable products and services and those who merely express concern about sustainability there are many other consumers: those who are taking action by buying sustainable products and services (albeit not at a premium) and those who are adopting sustainable behaviors (such as minimizing their water and electricity use, washing their clothes in cold water, restricting solo travel in automobiles, or using refillable packaging).

More good news: there are ways to reach and motivate these “in between” consumers by aligning sustainable offerings with their core needs . CEOs, chief marketing officers , and chief sustainability officers also need to understand the factors that currently deter consumers from more fully embracing sustainable choices and the factors that will motivate them toward sustainability. Then, CXOs need to learn to speak the language that will best resonate with consumers.

There’s marked variation across the product and service categories we examined. Some categories are more advanced on the consumer maturity curve, offering significant opportunity for companies to step up.

For instance, in home care products, nearly 60% of consumers say they are already following sustainable behaviors such as recycling products, bottles, and packaging (36%); using reusable cloths for cleaning (35%); and buying refillable cleaning and home care products (29%).

In the cars category, 39% of consumers report they are adopting sustainable behaviors such as avoiding driving or driving only when necessary (38%) or carpooling with others (14%).

The imperatives differ across categories, so the agendas for reaching consumers will differ as well.

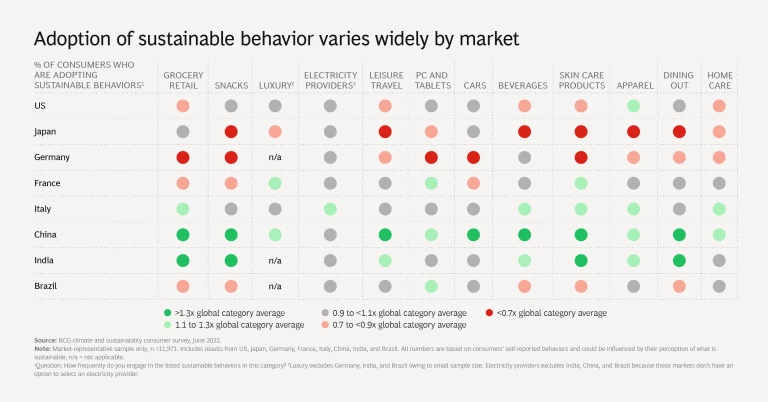

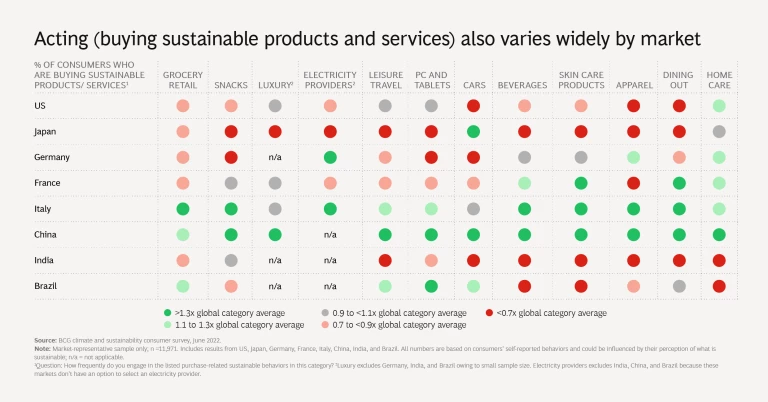

Our survey also revealed trends by country, with some surprises. We’ve seen that the greatest concern about sustainability comes from consumers in China (92%) for categories such as home care, cars, grocery retail, apparel, and skin care products and those in Brazil (89%) for select categories including home care, cars, and PCs and tablets. Concern is relatively high among consumers in India (84%) for cars. Among higher-income markets, Italy shows the highest level of concern (87%), particularly in electricity providers, home care, luxury, and PCs and tablets.

Heightened concern over sustainability hasn't always translated to action.

Possibly, the trends in emerging markets reflect localized and firsthand exposure to the harmful effects of nonsustainable behaviors. In certain markets, consumers may feel these effects more acutely, resulting in a heightened awareness of the need to act. In China, for instance, consumers witness firsthand the smog and pollution that result from nonsustainable practices. (Another possible reason for China’s progress on this front: government leaders may be emphasizing sustainable development.) Consumers in Brazil may have a greater understanding of and commitment to sustainability because they have a front-row seat to the unfortunate destruction of the rainforests. In some other nations, the true impact on environmental degradation may simply not be so obvious. Yet.

And the heightened concern doesn’t translate into action across markets. Consumers in China and Italy are generally embracing sustainability. But while consumers in Brazil and India are concerned, they tend to fall behind on adopting sustainable behaviors or buying sustainable products and services across most categories.

Driving Green into the Mainstream

Companies and CXOs will not fully maximize the potential of sustainable products and services if they focus only on increasing the percentage of consumers who are willing to pay more for sustainability—a segment that currently comprises just 1% to 7% of consumers. That segment is merely the tip of the iceberg.

Companies can move more consumers toward sustainable products and services by thinking about the different imperatives of the other three consumer segments. Those consumers—the ones who are concerned about sustainability, adopting sustainable behaviors, and acting by purchasing sustainable products and services—are high-potential silent stakeholders in sustainability. For example, we see that sustainable products and services have higher customer loyalty scores relative to nonsustainable alternatives. Having the right value proposition can not only encourage people to act and buy sustainably but also develop strong relationships and loyalty between consumers and brands.

By understanding the core needs of consumers, companies can significantly increase sustainable outcomes. Sometimes this will mean innovating to remove real barriers, and sometimes it will mean using communication to address perceived barriers.

The three imperatives for expanding the uptake of sustainable lifestyles are:

- Make claims locally relevant.

- Broaden the dialogue.

- Break the tradeoffs.

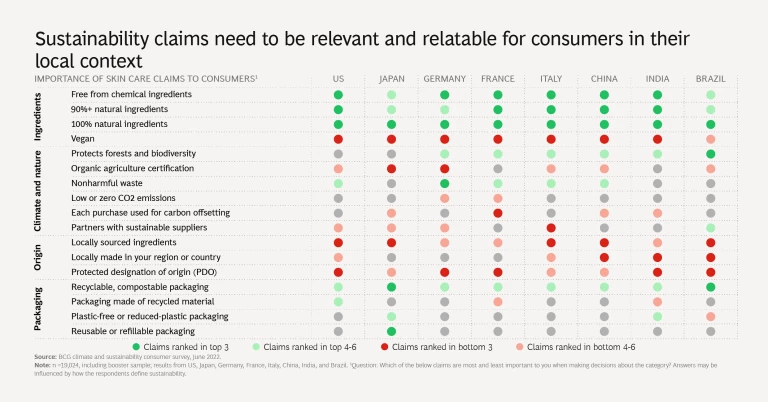

Make claims locally relevant. Among consumers who are paying more for sustainability or acting by making sustainable purchases, participation can be expanded if companies emphasize the legitimate, fact-based sustainability claims that resonate best given consumer perceptions—and thus spur consumers to greater action. (Remember, consumers are wary of claims that might be perceived as greenwashing.) CXOs need to speak the language of consumers rather than the language of their internal business team, regulators, or investors.

This language can differ in each country, so CXOs should use nuanced claims and language across markets . For instance, product claims that relate to protecting forests and biodiversity will resonate greatly for consumers in Brazil. Packaging is an issue of particular concern to Japanese consumers; they are likely to favor products that are recyclable, reusable, and made of compostable packaging or packaging that is free of plastics.

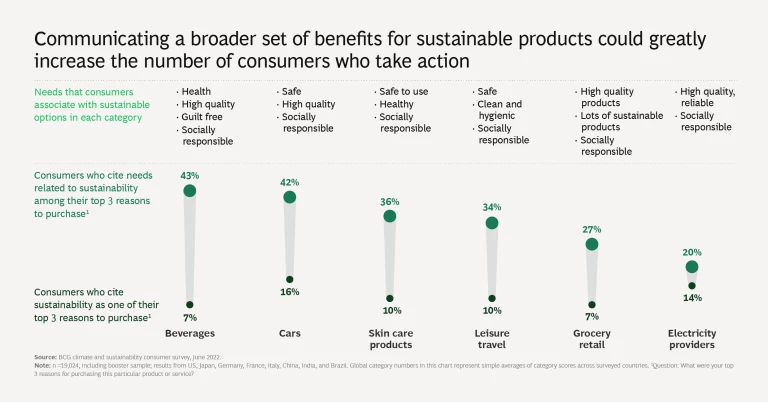

Broaden the dialogue. We found that, at most, 16% of consumers value sustainability for its own sake as a top driver of choice; this relatively small share of consumers said that sustainability was one of the top-three needs in their last purchase.

However, a significantly larger share of consumers (20% to 43% in the categories we tested) could be persuaded to make sustainable choices if the products or services also deliver other related and highly relevant needs.

In the beverages category, for instance, only 7% of consumers cite sustainability as one of the top three attributes they consider when making a purchase. But a larger share of consumers—as much as 43%—have top-three needs that don’t include sustainability specifically but are related to sustainability. These consumers seek beverages that are healthy, high quality, guilt free, and socially responsible—and all these associations are positively correlated with sustainable products. By broadening the dialogue to emphasize these related attributes in product design and marketing initiatives, companies can attract consumers to sustainable products even when consumers are not deliberately seeking them.

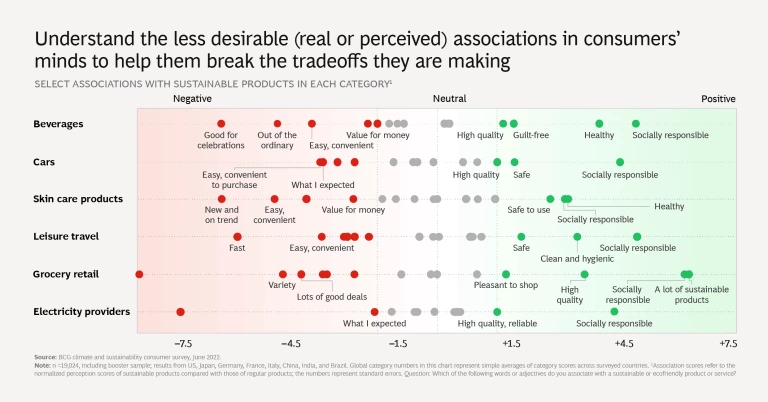

Break the tradeoffs. Consumers who express concern about climate and sustainability and those who are adopting sustainable behaviors can be reached through strategies designed to break the tradeoffs—the reasons why consumers hesitate to more fully embrace sustainability.

Sometimes these tradeoffs reflect real shortcomings. Companies’ sustainable offerings might not include appealing or acceptable products and services. Companies may offer less variety in the category of sustainable snacks, for instance, or a paper straw may be of poor quality relative to a plastic straw and therefore less convenient to use.

Alternatively, the tradeoffs may be misperceptions on the part of consumers. Many consumers think sustainable alternatives to products and services simply don’t exist, even when they are plentiful on the market. And consumers who are aware that sustainable products and services exist may assume that they are a lot more expensive than they actually are.

These may not be the only misperceptions posing barriers. Consumers may not understand the various ways to be sustainable—they might not know, for instance, that washing dishes by hand uses more water than a dishwasher.

Revisiting our example of beverages, we see that consumers believe sustainable beverages aren’t appropriate for celebrations, aren’t extraordinary, and aren’t a good value for the money. Companies will need to first understand the specific tradeoff that consumers are making and then plan solutions accordingly. For instance, advertising sustainable beverages as “fun” and “extraordinary” could enhance the image of the products as appropriate for celebrations. However, improving the actual innovation pipeline may be what it takes to make “good value” sustainable-beverage options available to consumers.

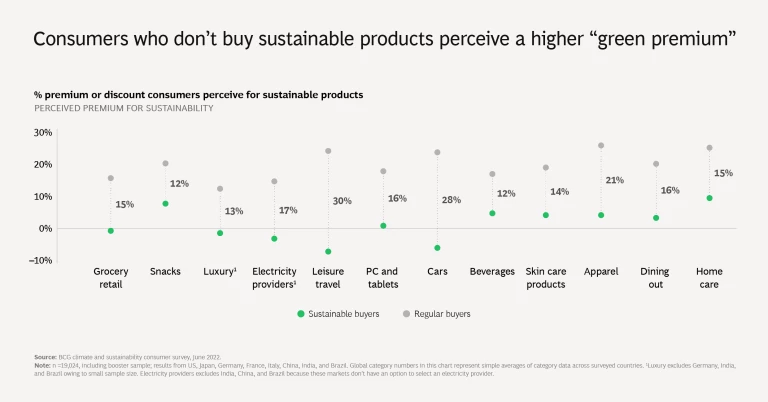

For many consumers who are concerned about climate and sustainability but are reluctant to act, cost is a primary issue. In fact, this is a key tradeoff. It’s also a great example of a negative perception that may not be justified. Our research proves that consumers who do not actually buy sustainable products tend to perceive a much higher “green premium” than the actual premium paid by consumers who do buy green products. Therefore, consumers who are on the fence about making sustainable purchases for reasons of price need to see clearer price communication.

There’s a big gap between consumer sentiment about environmental sustainability and consumer action for environmental sustainability. With consumer-centric data in hand, CXOs can:

Making sustainability an “and,” not an “or,” will be a win for the environment and your company’s bottom line.

The authors thank Aditi Bathia, Ankur Jain, Gaby Barrios, Sarah Lichtblau, Gabrielle Salvado, Henry Fovargue, Andy Reilly, and Julien Dangles for their contributions to the research and insights informing this article.