Finland is failing to embrace the business imperative of diversity. While socially it is one of the most gender-equal countries in the world, it is falling behind in women’s share of corporate leadership. Moreover, it has made little headway in promoting other kinds of diversity, especially sexual orientation and nationality. By promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in these new areas, and at the same time advancing on gender, Finland can achieve its full business potential. It’s time to run!

The Value of Diversity in Finland

Diversity is not just a moral imperative, but also a key lever for improving business results. As Ahlström suggests (see below), diverse groups can not only broaden the range of ideas and projects, but also promote higher performance in everyone. By linking a diverse workforce to business value, companies can better translate their ambitions into tangible progress.

While it is important to look at diversity broadly, companies must first define, measure, and improve in dimensions that are easily quantifiable. Only then can they tackle broad but vague definitions.

BCG’s recent global report “

Finding the Value in Diversity

” highlights the opportunity from a diverse workforce. Where women hold at least 30% of the leadership positions, companies have a net profit margin 6 percentage points higher than the average.

"While working nine years abroad, I saw how diverse companies can create motivating, high-performing working cultures. When leading organizations in Finland, I have wanted to create the same kind of high-performance culture with diversity and inclusion playing a key role in achieving this.

On this journey, understanding the starting point is important. Fiskars Group already has a good gender balance, so diversity comes from people’s backgrounds more broadly. We have also put a lot of effort and attention into recruiting diverse talent for key leadership teams and, most importantly, we’re building an inclusive culture where everyone feels safe to speak out. The next steps for us are to strengthen our understanding of how DEI creates value throughout the organization and to take the performance culture further through our leadership journeys."

—Nathalie Ahlström, CEO, Fiskars Group

Hiring and promoting diverse employees is not enough; to make sure everyone can perform to their full potential, companies need to boost equity and inclusion. These may be particularly urgent for LGBTQ+ employees. Another global study by BCG suggested that LGBTQ+ employees experiencing negative touchpoints are 40% less productive and 13 times more likely to quit. For all employees, people who feel valued and respected are 30% more likely to actively seek promotions.

Many Finns agree with the diversity imperative. Our survey of employees at nine leading companies in Finland from different industry sectors suggested that 95% believed DEI is crucial for future competitiveness, and 65% said their organizations were missing out on talent, innovation, and creativity due to insufficient DEI.

Methodology

To understand Finnish attitudes and practices on DEI, BCG interviewed the leaders of ten major Finnish companies and three large universities. We also surveyed 1,480 employees at nine of these companies, of which eight have operations around the world.

In this report, “diversity” refers to a company broadening its leadership or employees beyond the majority groups by gender identity, nationality, and sexual orientation. “Normative” refers to survey respondents who belong in the majority in these three dimensions, while “diverse” refers to respondents in the minority on any of them. We also consider at times a broader definition of diversity, by age, education, religion, family status, physical and mental ability, appearance, socioeconomic status, and the unique strengths of individuals.

Most efforts to boost diversity focus on identifying and recruiting talent. By inclusion, we mean enabling and retaining this talent and advancing their career progress. Equity involves creating fair access, opportunity, pay, and benefits for diverse employees on par with the majority.

Other stakeholders are also demanding greater DEI efforts. Customers are beginning to choose their purchases based on the seller’s social responsibility. Investors are including a company’s overall contribution to society in their decisions. In our Finnish survey, 20% of respondents said that a company’s inadequate DEI was one reason they’d quit or hold back from applying to work there.

Finally, by addressing diversity and equity issues and ensuring all employees feel included, companies will strengthen their culture—which benefits the organization as a whole.

Technological and geopolitical changes are adding to the urgency of diversifying company perspectives. Both B2B and B2C companies are dealing with a variety of transitions, from digitalization to the shift to a service-dominated society. Organizations with a range of voices throughout the ranks are better able to innovate, take risks, solve problems creatively, handle crises, and turn challenges into opportunities.

Additionally for B2C companies, a diverse workforce will better understand the needs of their increasingly global customer base. Without a broad perspective, even such highly successful companies as Apple can make errors. The company released a comprehensive health application in 2014 without menstruation tracking, and then in 2017, its initial facial ID recognition software didn’t work for Asian customers.

By contrast, diversity can improve the customer experience and broaden the customer base. When Lenovo developed its augmented-reality (AR) headset, it ran extensive tests with participants varying by gender, ethnicity, height, hairstyle, and use of glasses to achieve a broadly popular design. In 2018, Nike launched a campaign around racial equity resulting in a $6 billion increase in market value and a 30% sales boost.

“Valuing talent from diverse backgrounds, rewarding performance, and providing equal opportunities for advancement are key principles for us at Fortum. I believe that we are more competitive and can better meet the expectations of our customers and society when there is diversity also in our management. This is not a given in the traditionally male-dominated energy sector, and, in fact, our goal is to build a corporate culture in which our employees from different backgrounds can thrive, develop, and perform their best.”

—Markus Rauramo, CEO, Fortum

B2B companies are likely to benefit especially from how diversity encourages cross-disciplinary collaboration, which is needed to address the increasing complexity of business. Breakthrough solutions to client challenges often depend on varied sources of information and connections across professional disciplines. Volvo, for example, works systematically on DEI because its internal studies show that diverse teams are more creative and efficient.

Diversity similarly yields greater knowledge of customers. A survey by Harvard Business Review Analytics found that a team with at least one member sharing a client’s ethnicity is much more likely to understand that client.

How to Move Ahead on Diversity in Companies

Finland has a reputation as an equal opportunity society, especially on gender. The World Economic Forum’s 2021 Global Gender Gap report ranks the country second overall in the world after Iceland. But Finland is a distant 51st in managerial and senior official roles. This is even worse than the report’s first edition in 2006, when Finland was 46th. The strong overall rating can be attributed to political empowerment and gender diversity in public sector positions, but when it comes to the private sector, Finland is not keeping up with global progress.

Only a quarter of publicly listed company leaders in 2021 were women, and women held fewer than 15% of positions with bottom-line responsibility (C-suite and business unit heads). As these roles are typically stepping-stones for the CEO position, men will likely also dominate the next wave of CEOs.

Senior leadership also fails to reflect their customer base. Of those higher positions in Finland’s largest 30 companies, not only do men hold 87%, but Finns hold 61%, even though half of their customers are women and two-thirds of their revenue comes from outside the country.

It’s true that Finnish women are becoming highly educated, even surpassing men in total degrees received. More than half of the recipients of graduate degrees are women.

Beyond gender and nationality, companies are aiming to extend DEI to sexual orientation, disability, age, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. So far progress has been limited. The diversity gap on sexual orientation between customers and employees may actually be rising, as companies risk losing out on substantial talent who prefer to work outside of hierarchies.

In BCG’s global research,

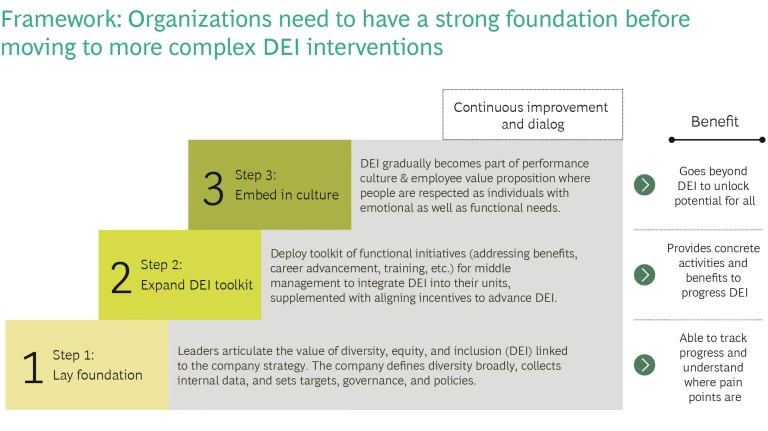

Many Finnish companies have plans for actions, but no systematic approach for making progress. To help address this challenge, we propose a three-step maturity staircase. This will help companies determine their starting point and understand the next steps needed for DEI (see Framework).

The first step is to lay the foundation with a broad definition of diversity. Top management needs to articulate the value of DEI for the company’s strategy and implement targets, governance, and policies. The second step goes into day-to-day processes with a toolkit of initiatives for middle managers to meet employees’ functional needs such as work-life balance, career advancement, and content of work. Finally, step three is to embed DEI into the company culture by also addressing the emotional needs of individual employees. Emotional needs can include, for example, feeling challenged or valued at work (you can learn more about the functional and emotional needs of employees from our recent report “ Reinventing Gender Diversity Programs for a Post-Pandemic World ”).

Finnish companies are at different stages of maturity now, but none of them (and no organization globally) are fully mature in terms of DEI. This is partly due to the evolving nature of DEI, which means that the end of step three is establishing continual improvement and dialogue (in- and outside of the organization).

Accelerating Diversity: Laying the Foundation

Let’s delve into this framework, starting with step one. The essential act is grounding the company’s commitment to its strategy. All companies can appreciate what we described in section one, how diversity promotes innovation, creativity, and customer engagement and encourages higher performance from everyone. But translating those benefits into a strategic imperative often requires setting out a clear narrative to align everyone.

Many Finnish companies are still at step one. According to our survey of Finnish companies, only half of respondents say they understand their firm’s DEI strategy and objectives.

Among the interviewed companies, KONE, for example, has “being a great place to work” as one of their strategic targets. In addition to promoting a diverse workforce with an inclusive culture, the company has sought suppliers with diverse workforces.

Aside from linking DEI with the strategy, companies should define their purpose broadly enough so that it inspires a diverse workforce and leadership. This is also key in recruiting and retaining talent: in the Finnish survey, having a purpose was the most frequently highlighted factor when selecting a job.

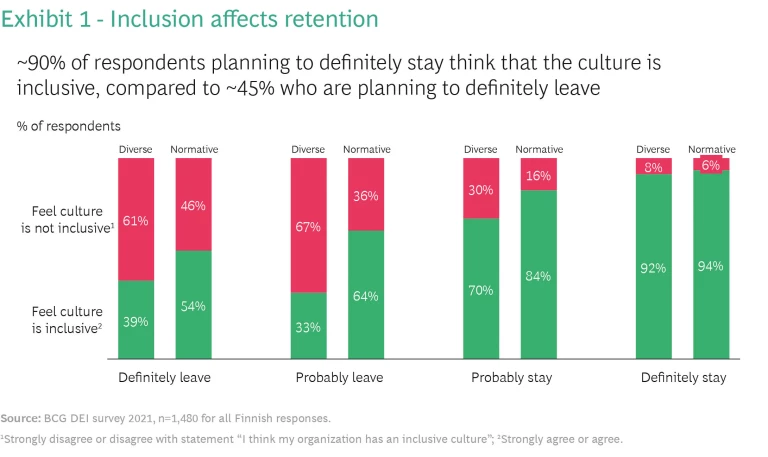

Inclusion is essential, as the Finnish survey suggests a correlation between inclusion and retention. On average, 90% of respondents who definitely planned to stay deemed their culture inclusive. Of those who definitely planned to leave, only 45% found it inclusive (see Exhibit 1).

Supercell’s strategy makes the connection explicit, telling employees that the company won’t achieve the diversity required for innovation unless it first embraces inclusion.

Besides linking diversity to strategic imperatives, the step-one narrative should specify the business value to be created. Nokia expects its DEI to become a key competitive differentiator—so everyone knows the high stakes. The business case summarizes the imperative: “We know that a diverse team will help us best answer the future challenges faced by the very technology we are developing and deploying.”

As companies continue to focus on gender and nationality, most also need to begin working on the more subtle dimensions of broader diversity, such as sexual orientation, education, and unique strengths of individuals. Merely collecting data on broader dimensions is difficult, but without measurement, leaders won’t be accountable for progress. Not considering diversity, or addressing it narrowly, risks missing out on talent.

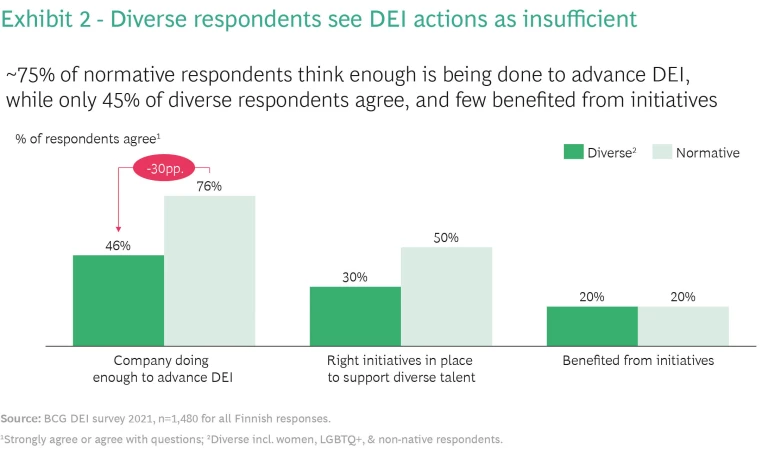

The Finnish survey suggests that three-quarters of normative respondents think that companies are doing enough to advance DEI, while only 46% of diverse respondents think so. Also, only 30% of diverse employees think that the proper initiatives are in place to support them, and even fewer (20%) have benefitted from DEI initiatives (see Exhibit 2).

We recommend that companies work with a broad definition of DEI and collect input from employees on the dimensions that matter. OP Financial Group, for example, had long sought diversity by gender, but now it also includes sexual orientation and disability, as well as industry-specific areas such as educational background, as key areas of diversity to consider. (The financial industry has been biased toward degrees in business or finance.)

Companies can empower employees through setting up employee resource groups (ERGs). For example, Fiskars Group has recently started an ERG for women in business. It plans to potentially add other ERGs based on employees’ interest.

Likewise at BCG, the Pride@BCG provides community and career support for LGBTQ+ employees. The members can choose if they want to be out to the whole organization, only group members, or just follow internal communication confidentially. BCG’s research

Once companies have clarity on the dimensions that matter and where they are in terms of DEI, they can develop specific initiatives and metrics. Without measurement and accompanying accountability, companies can’t track the effectiveness of their actions.

Most companies already have basic metrics in place to track end goals, such as share of women or non-Finnish employees in the organization. Others include the age distribution in the various career steps. But they aren’t systematically using their data to promote transparency, draft effective initiatives, or incentivize management.

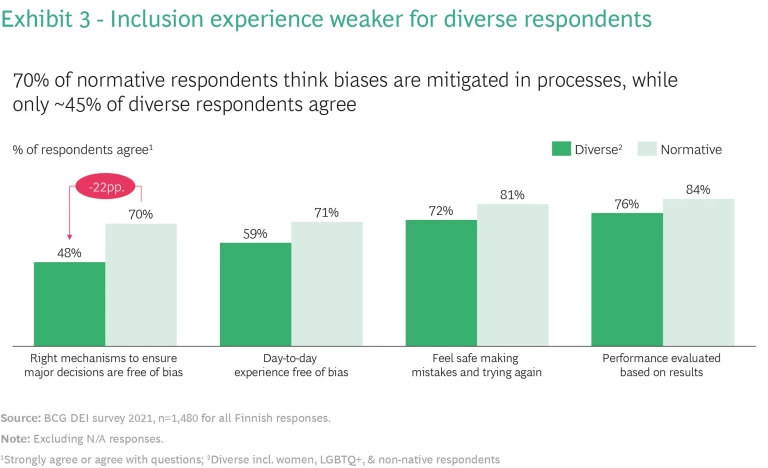

Without accountability, including concrete data on actual trends, companies too easily slip into marginalizing the non-majority groups. In our study, only 46% of diverse employees felt that there were good mechanisms to ensure major decisions were bias-free, such as for promotions. That’s a drastic difference from normative respondents, 70% of whom said those mechanisms were in place (see Exhibit 3). Without robust mechanisms, it’s too easy for people in authority to show bias in evaluating colleagues who are different from them.

We recommend that companies first ensure their HR system captures data on basic metrics, such as age, nationality, gender, sexual orientation (see “Supporting the LGBTQ+ Workforce”), and education.

Supporting the LGBTQ+ workforce

IBM has offered a self-identification option for employees since 2006.

Another helpful practice is to promote standardized data collection across the organization to enable easy comparison across units. That’s what happened at GAP, a global retailer. To improve its decisions on managing people, it standardized HR data across all its brands worldwide, including regarding sexual orientation.

At Neste in Finland, individual teams began using newly accessible data to better manage their talent. One leader pointed out, “Even though many teams are taking small steps, we already see that the discussion is completely different when it’s data-driven.”

Back in 2018, Nokia defined the inclusive day-to-day behaviors it wanted to see exhibited more in the organization. Since then, it has set targets for inclusiveness and measured progress against them in each business group and function. The feedback given by the employees steers the yearly DEI initiatives and agenda setting which have led to a visible decrease in exclusionary behaviors and increase in feelings of belonging. The company has also defined diversity expectations for its management to drive progress. Also, transparency drives progress. Hence, Nokia started in 2020 to publish externally and internally its key diversity data. For continuous improvement it participates yearly in global benchmarks, such as Bloomberg Gender Equality Index as well as Workplace Pride and Human Rights Campaign Foundation’s survey on LGBT+ inclusivity.

As the data comes in, it’s usually helpful to share findings in internal communication. Some companies have set up live dashboards for management to make it easy to follow metrics and progress. UPM has included DEI metrics on each business unit’s scorecard, providing transparency to potential issues and keeping the topic top of mind for leaders.

Besides making the case for relevant DEI and collecting data, companies should confirm that the main DEI rules are on the books, especially anti-discrimination policies, clear evaluation criteria, playbooks for unbiased recruiting, and neutral vocabulary in job postings. They will likely need to review current HR policies to discourage unconscious bias.

“I am absolutely convinced diverse teams make better business decisions. Also, our customers and end users are diverse, so to really understand them and their needs, we need to be diverse.”

—Henrik Ehrnrooth, CEO, Kone

Direct Actions to Promote DEI: The Functional Toolkit

All of these efforts—connecting with the strategy, broadening the diversity dimensions, and collecting and sharing data—lay the foundation for speeding up DEI. From there, companies can work directly to promote these goals. While DEI progress in society generally will help enormously (see “Support from the Wider Society”), companies can still accomplish a great deal on their own.

Support from the Wider Society

They can also facilitate a shift in traditional gender roles, as Finnish women typically use 98% of postnatal leave days. Overall, 92% of those caring for a child are women. This imbalance feeds implicit gender bias, as mothers who took family leave for up to two years earned 8 to 11% less upon returning, while men were unaffected.

Finland already has a solid infrastructure, such as its daycare and education system, to support DEI. But the society can do more here by promoting DEI through education. Schools could include DEI in curricula, adjust career planning to overcome traditional biases and narrow choices, promote diverse role models, and better support foreign students.

Most companies are already working on diversifying their recruiting. Success here depends on finding and attracting a broad base of talent. For gender diversity, the main recruiting challenge is having men-skewed recruiting pools across focus study areas such as technology, engineering, and finance. Companies can actively collaborate with universities to encourage more women in these fields. But they can also tell students about career paths for people studying other areas.

For nationality, the great challenge is to attract and keep talented people in Finland. Non-Finns struggle with integrating into Finnish society, language barriers, limited schooling for expatriate children, finding employment opportunities for their spouses, as well as a pay gap relative to most other Western countries. Although 13% of graduate degrees from Finnish universities are awarded to international students, only a third of these students are employed in Finland five years after graduation.

Some companies are making progress. KONE has launched focused recruiting initiatives, with goals shared among HR and partners to build diverse pipelines and certify DEI recruitment standards. Shell has developed an attractive value proposition for women graduates, including women’s leadership development programs for employees and managers.

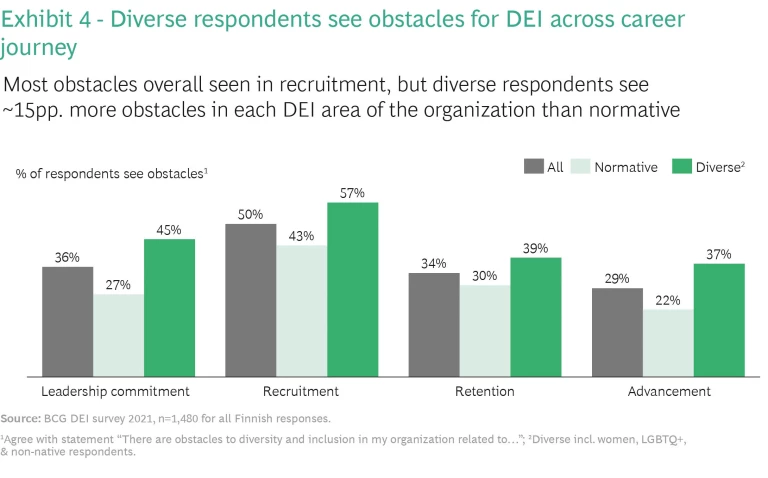

Inclusion—especially retaining and advancing diverse employees at a pace equal to normative staff—may be the greater challenge. In the Finnish survey, normative respondents focused on DEI challenges in recruiting. Diverse respondents, by contrast, saw obstacles across the career journey, with too little leadership commitment to retention and advance (see Exhibit 4).

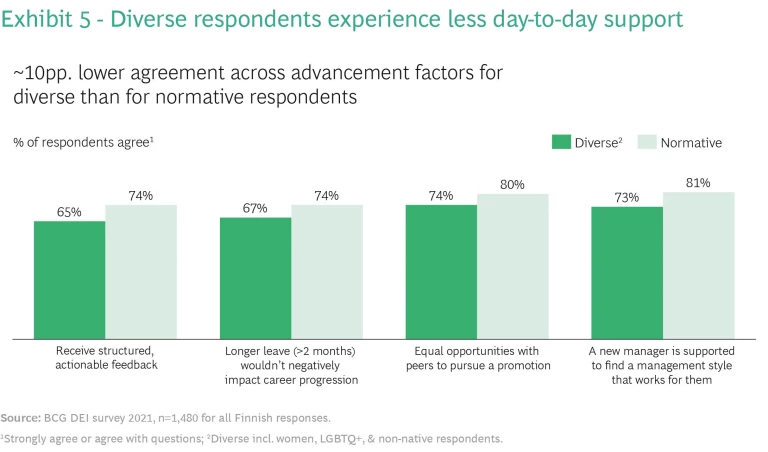

Many companies seem to lack mid-management commitment and know-how to push inclusion in day-to-day operations. Too many managers believe diversity is a matter of recruitment only, or they end up unconsciously biased toward people similar to themselves. Unconventional recruits are likely to receive less onboarding training, senior support, or mentoring and may not gain equal career-development opportunities. Perhaps most important, many managers don’t know how to lead diverse teams and take advantage of diversity. In our Finnish survey, diverse respondents experienced around 10 percentage points less day-to-day support than did normative respondents (see Exhibit 5).

This gap between diverse and normative employees arises because of the lack of robust implementation plans and tools. Many companies cite DEI as a corporate principle, but without putting it actively on the management agenda. They lack the knowledge to push the issues forward. So they relegate it to HR departments, which then struggle to get business unit leaders to embrace their initiatives. These organizations lack concrete roadmaps to follow.

Here as well, they can draw on examples. Some companies are making good progress, especially after the foundation work of data collection. Nokia eliminated its unexplained wage gaps after reviewing the pay of its 100,000 employees around the world detecting a small, but statistically significant pay gap. The gap was closed for everyone, however about 90% of the beneficiaries were women. Other companies, such as UPM and Wärtsilä, have made similar efforts.

To close the gender gap in the career effects of extended leaves, companies can draw inspiration from SAP and Spotify. These firms have introduced long-term work-from-anywhere policies and made flexible working part of the company culture and standard practice.

Other companies are getting creative. Roche is running a pilot program where new-parent employees receive a benefit (€10,000–€15,000) if both parents simultaneously reduce their schedule to 28–32 hours per week for at least 12 months. The goal is to encourage equal sharing of childcare and keep both parents engaged in the workforce.

Employee training can help with operational support, for both management and the broader organization. Fiskars Group has rolled out trainings on unconscious bias and DEI first for their HR colleagues, then for management, and finally for all employees. Neste trains its managers on “inclusive leadership and the culture of belonging” and communicates this imperative across the organization. Wärtsilä has held a series of “Diversity Talks” in a townhall setting around its campuses to drive conversation on how individual actions and mindset can impact the company and society.

The goal is to get everyone, including middle managers, to promote inclusion in their day-to-day operations. That means ensuring everyone is heard, making it safe to propose novel ideas, sharing credit for success, giving actionable feedback, and respecting feedback from the team. Fortum’s “open leadership” model embraces these practices. Based on positive psychology, it emphasizes placing trust on everyone to deliver their best, sharing opinions candidly, and taking care of employees’ well-being.

In order to get the entire organization on board, leaders need to keep DEI on the agenda beyond the year when activities are launched. It’s not just a workshop, it is a journey. Eventually, the target should be to embed DEI into the company DNA, reflected in its values and processes throughout. Sanoma has long encouraged listening to employees’ input and building trusted relationships with managers, yielding an inclusive environment without yet resorting to structured initiatives. The DEI journey has now been started with a clear focus on first increasing awareness and understanding and moving toward needed changes in behavior and practices. The journey should get easier over time as more layers of the organization become diverse, changing the overall mindset and making it easier to relate to varied employee needs.

Embedding Into Culture: Addressing Employees’ Emotional Needs

Early in a company’s DEI journey, it is practical to treat diverse groups as having a similar set of experiences and needs. This helps ensure that the organization delivers on the needed building blocks while meeting employees’ functional needs with benefits, work-life balance, and career support. But serving only these functional needs does not ensure retention and engagement in the long run.

While harder to articulate, emotional needs correlate better with happiness at work.What is more, these needs can vary greatly from one person to another, so companies need a tailored approach here.

The BCG article “ Reinventing Gender Diversity Programs for a Post-Pandemic World ” explains how companies can go beyond and address employees’ emotional needs. For example, BCG researchers grouped US women employees into 11 segments based on key needs such as importance and content of work, fair treatment, feeling appreciated, and being challenged. The results transcended simple demographics. The “Salaried and Stable” and “Senior Empty Nesters” both were older with kids, but their attitudes toward work differed enormously. The former were interested in stability and benefits, whereas the latter wanted to be challenged and feel engaged.

Even the functional initiatives rely on understanding these emotional needs. A flexible work program where you work only 80% of the week is good on paper, but it falls apart if the participant does not feel like a valued member of the company—if, for example, the organization doesn’t champion the program and participants have to constantly remind their managers about the shorter work week or are excluded from events or meetings.

From such needs-based segmentation, companies can create directed employee value propositions that improve employees’ happiness and motivation—as well as inclusion. This focus on emotional needs does expand beyond conventional DEI, but it benefits the entire workforce and creates a more attractive and better performing organization.

“We need a psychologically safe workplace where people can be themselves. Companies that are good at diversity and inclusion and have a capability to turn them into learning and improved collaboration actually achieve better financial results. But it's not only that, for Nokia it’s also simply the right thing to do.”

—Pekka Lundmark, President and CEO, Nokia

The Way Forward

DEI is a process, not a simple target or program to be adopted. Here we have laid out a three-part process. The foundational step is to embrace diversity as a business goal, supported with equity and inclusion and made concrete with targets, governance, and policies. The next step is to launch initiatives not just to broaden recruiting, but also to give the broad organization the tools and know-how to push inclusion into the business units. The third step is a long-term effort of promoting inclusion in the day-to-day work, interactions, and culture of the organization.

In order to accelerate DEI in Finland, ten companies, three universities, and two ministries have joined the Diversity Roundtable facilitated by BCG and UN Women Finland. We would very much like to thank the roundtable members for active discussion and development around DEI and this report. Roundtable members: Fiskars Group, Fortum, Kone, Neste, Nokia, OP Financial Group, Sanoma, Supercell, UPM, Wärtsilä, Aalto University, Hanken School of Economics, University of Helsinki, Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment, and Ministry of Education and Culture.