When Unilever unveiled its plans for a radical restructuring earlier this year—including a reorganization around five category-focused business groups and the elimination of a layer of senior and middle managers—Alan Jope, the company’s CEO, explained that the changes would make the UK-based consumer goods multinational more responsive to customers by giving “crystal-clear accountability for delivery” to executives at the customer interface.

Scale isn’t dead. But it’s critical to find the right balance between scale and fractal principles—and to do it before your competitors do.

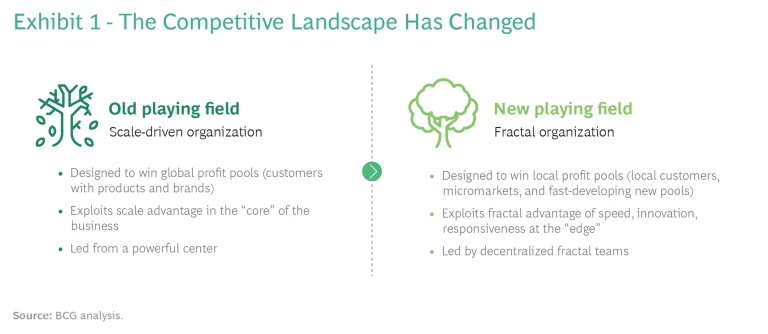

It was the latest sign that global businesses are rethinking what has long been the winning formula for profitable growth. Until recently, companies could successfully compete for global customers, products, and brands by focusing on scale and efficiency under the direction of a powerful central leadership. The new winners, as Unilever’s Jope acknowledged, will be those companies with teams on the ground that are laser focused on winning local customers, micromarkets, and fast-developing profit pools. Scaling the core—a formula developed for a stable, integrated, globalized economy that is rapidly fragmenting—has given way to innovation, speed, and responsiveness at the edge. (See Exhibit 1.)

In a previous article , we described how this fragmentation was being driven by three powerful forces: the influence of geopolitics, particularly the decoupling of the US and China; digitization’s impact on the value chain; and the growing number of “ deep tech ” innovators winning the product-development race. These forces are reshaping the competitive landscape in a fundamental way. Many incumbents, unable to compete, are actively descaling their global footprints. At the same time, a growing list of subscale or “scale-disadvantaged” companies—startup innovators, local consumer companies, large but nimble digital giants with no residual scale in a particular industry—are beating their much larger global peers by exploiting a new source of competitive strength.

Many global companies are struggling to adapt to fractal advantage—while subscale companies are often thriving.

We named this new source of strength the “fractal advantage.” And many global incumbents are struggling to adapt to it—while subscale companies are often thriving.

Why is this? What’s so special about the way these fractal companies are organized (perhaps unknowingly) that allows them to compete and win—even though traditional management theory, with its emphasis on maximizing the value of the core and extracting the economies of scale, does not give them much of a chance?

As we dug deeper into this question, interviewing leaders of dozens of successful and not so successful companies—from startups to global behemoths and digital giants—we came to two surprising conclusions. First, scale and fractal strategies rely on fundamentally different organization principles. It takes more than a few minor tweaks to turn a company designed for scale advantage into a company that can successfully exploit fractal advantage.

Second, while incumbents do not have to disavow scale to instill fractal principles—they are, in fact, two ends of a continuum—finding the winning balance before your competitors do is critical. And so far, many companies seem to be getting it wrong, in terms of both the balance and the speed.

The “Scale Versus Fractal” Continuum

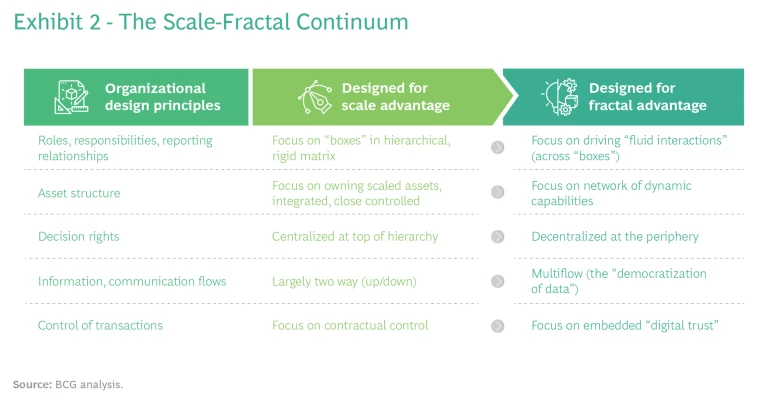

Over the past 50 years or more, as the global economy became more integrated, CEOs have built their organizations to exploit scale as a source of competitive advantage. They have built massive workforces, large factories and other capital assets, and continent-spanning supply chains. They have constructed gleaming central headquarters, where they retain all the important decision rights and exert tight control through a rigidly hierarchical and complex matrix management

Let us now lay out the fractal end of the continuum, based on the same five dimensions of organization design:

- Roles, Responsibilities, and Reporting Relationships. Fractal companies are less focused on hierarchy and more focused on maximizing interactions, links, connections, and conversations across hierarchical boxes—including employees, customers, and external partners.

- Structure of Value-Creating Assets. Fractal companies design their delivery models around a network of dynamic, continuously evolving capabilities—their own and those belonging to their partners. These capabilities can be deployed quickly at local and micromarket levels and to target new value pools.

- Distribution of Decision Rights. Fractal companies are decentralized and distribute significant power to customer-facing teams at the periphery.

- Flow and Management of Information. Fractal companies democratize data (to the extent possible) with a real-time, transparent, multidirectional flow across boxes and organizational boundaries.

- Management and Control of Transactions. Fractal companies build digital trust to facilitate an environment of sharing and to grow online transactions in an increasingly digital business environment.

We have presented the fractal company as the polar opposite of the scale-driven company to emphasize the profound differences in their organizational designs. For most incumbents, however, fractal characteristics will coexist with many elements of scale, though the latter will need to be redefined. (See Exhibit 2.)

Even in an industry as scale-intensive as steel, a fractal competition is emerging, as T.V. Narendran, the CEO of Tata Steel, told us in a recent conversation. He described the company’s fast-growing consumer solutions business, where (in contrast to its traditional B2B business) competitive advantage will not be driven by the scale-driven cost efficiency of the steel mill but the fractal advantage created by speed and innovative solutions—allowing the company not only to respond to customer needs but also to shape them.

The Fractal Design Principles

We will now provide more granular detail about each of these design principles and show how business leaders can incorporate them as they prepare their company for the fast-changing competitive environment.

From Efficient “Boxes” to Interactive “Links.” When asked what one thing he would like to change to be more competitive in his local market, a senior manager in a global consumer company told us, “I wish I [could] call up the global R&D head and discuss the product tweaks I need to respond to competitors. I need to get it done in a month and not [the] year that it takes at present, and [I need to know] if my request is aligned with the R&D’s own priorities.” Hierarchies, organizational boundaries, and the rigid efficiency metrics they impose on the specific “boxes” of an organization chart both slow down decisions and constrain local in-market innovations. The fractal company is in a sense antihierarchical and structures all roles and responsibilities in fluid and flexible ways to maximize the number of interactions and “links” across boundaries—which drives more “out of the box” ideas and allows teams to form and act on them at speed.

Scale-driven incumbents have approached the need to become less hierarchical with varying degrees of urgency and success.

Relative digital newcomers with no legacy hierarchy to deal with, such as SalesForce.com in the US and ByteDance in China (the technology company behind TikTok, the world’s fastest growing short-video app), have designed their organizations ground-up to be fluid and nonhierarchical. One senior leader of ByteDance claimed to us that the company is built to work on new ideas and current problems two to three times faster than its peers. It achieves this through:

- De-emphasizing hierarchical levels and spans (they do not use titles in their communications) and giving more importance to roles and team outcome than to seniority.

- Establishing the ability to rapidly orchestrate global teams with the best capabilities as the business-as-usual way to operate.

- Transparently facilitating and tracking every employee’s individual and team contribution. For example, each of ByteDance’s 100,000-plus employees—including Liang Rubo, the company’s CEO, and Shou Zi Chew, the CEO of TikTok—participate in teams that deal with every type of business activity, from routine work to the development of new ideas with commercial potential.

To support this fluid and highly interactive organization they use a management tool called OKR (Objectives – Key Results). Modelled on the OKR system pioneered by Andy Grove at Intel and later refined by Google, ByteDance’s OKR system is fully transparent: every employee can see the OKRs of everyone else, including those of Liang

Scale-driven incumbents with large legacy organizations have approached the need to become less hierarchical with varying degrees of urgency and success. Some are making it easy to cut across organizational boundaries and boxes to set up task-focused teams. Others are intent on increasing interactions and engagement with customers. Siemens, for example, has built a global network of digital customer centers to bring customers and partners together with internal specialists who would otherwise work mostly within their hierarchies.

Natura, the Brazilian cosmetics giant, has begun adapting its traditional matrix structure by forming a network of horizontal and diagonal links, or “bridges,” across the usual vertical lines; the resulting lattice structures, with their crisscrossing links, promote the greater lateral thinking that companies need in order to build a distinctive position in the market. Roberto Marquez, Natura’s chairman and group CEO, says that this crisscross approach promotes a better balance between the efficiency that comes from global scale and the innovation, speed to market, and customer responsiveness that comes from local ownership of the

From Fixed Assets to Flexible Capabilities. Tata Steel’s Narendran sees a future where its Indian consumer-solutions business will be built very differently than its traditional steel business. Instead of a few large-scale plants supplying all markets, the consumer-solutions business will be supported by a network of smaller in-market assets that the company does not necessarily own—electric arc furnaces, for example, which use scrap steel and are often powered by renewable energy, and which (unlike traditional-scale blast furnaces) are cost effective at lower volumes. The winning formula is not cost efficiency but the fractal levers of speed and local innovation in offering customized steel solutions, delivered by this capability network of “microassets.”

Typically, service companies (for example, information technology or consulting firms) find it easier to organize themselves as a global network of highly dynamic capabilities for delivering local, customer-specific solutions. This is because they do not have to dismantle any large, fixed, and built-to-last legacy assets. Incumbents in traditional asset-heavy industries are building similar fractal global delivery networks by exploring three complementary approaches, especially as the functionalities and performance of even physical products is increasingly driven by software.

The growth of technologies such as 3-D printing has paved the way for microfactories located closer to a company’s customers.

First, like Tata Steel, they are experimenting with “descaling” their large fixed assets and “deintegrating” their global integrated supply chains (which can be efficient but slow) for target markets and customer segments. The fast-paced growth of technologies such as 3-D printing has made this possible by paving the way for microfactories located closer to a company’s

Second, incumbents are starting to “deassetize” their large, owned, fixed asset base by migrating to local, fast-response “asset-as-a-service” providers that rent out fixed assets which were once regarded as core. While data storage and management has long been purchased in this way (thanks to Amazon Web Services and Microsoft), companies seeking to rapidly scale up new offerings in local markets now can rent everything from logistics, sales and marketing, and recruitment services to distribution and even core manufacturing (from companies such as Germany-based FlexFactory). Xiaomi Corporation, a China-based electronics business, has used this local asset strategy to become the third-biggest mobile phone player in the world in just over a

The third leg of the global capability network is a growing ecosystem of local partners that bring new, often fast-evolving digital capabilities in highly flexible and innovative ways. For example, John Deere, the world’s largest manufacturer of tractors and other agricultural machinery, has built a comprehensive digital network that brings together the Internet-of-Things (IoT) capabilities of its own machines with an expanding set of capabilities provided by external partners, from agronomic and weather analytics to soil-monitoring sensors, real-time profitability per acre calculations, and drone field-mapping. With this constellation of capabilities, John Deere can offer customized solutions to help farmers become more

Over time, as these individual approaches are scaled up, traditional globally integrated supply chains will evolve into global networks that combine some large-scale assets (where cost efficiency is still critical) with in-market microfactories, rented assets-as-a-service, and local ecosystems of digital capability partners.

From Central Control to Peripheral Power. A CEO (and promoter) of a local Indian consumer company, when asked for reasons behind the company’s gain in market share relative to its much bigger global peers, simply said that he was just a “floor away” from his team. No multinational corporation, with its global hierarchy, could match his company’s speed of response to fast-changing customer needs. Perhaps he was boastful, but it reveals a basic truth: fractal companies build their organizational design to promote faster decision making. They do this by redistributing the power to make decisions—and allocating resources—to customer-facing leaders stationed far from the center.

For scale-driven companies with a long-established culture of top-down decision making, the process of decentralization is difficult. They fear what they might lose by increasing fractal advantage more than what they might gain. Procter & Gamble has found its own answer to this conundrum. After simplifying its organization by selling more than 100 brands and creating six global businesses, P&G divided its global market into two parts: core (focused on about 10 countries that account for the majority of its sales and profits) and enterprise (focused on the rest of the world). In their most critical core markets, P&G fully empowered—with profit-and-loss responsibility—the CEOs of the six individual businesses to spot and respond quickly to changing market and competitive conditions, providing them control of all necessary resources, critical decision rights, a simplified reporting structure, and most importantly the “intelligence” in the form of data collection and analytical tools and capabilities.

For companies with a long-established culture of top-down decision making, the process of decentralization is difficult.

Meanwhile, for the smaller enterprise markets, P&G has created businesses around clusters of countries, each with its own empowered CEO. The traditional regional structure, the hallmark of the hierarchical matrix that enabled better control but slowed decisions, has been hugely simplified; the central functions focus on long-term strategic plans, research and development, and IT and new technologies. For P&G, this fractal approach appears to be working well: it has posted some of its best results since the launch of this new organization design.

Other companies, such as Zappos, the US-based online fashion retailer, or Haier, the China-based global leader in appliances, have gone to the extreme “fractal” end of the continuum. They have turned the traditional center-down design of scale-driven companies on its head and built their organizations up from semiautonomous teams at the periphery. For example, Haier’s organizational model, called Rendanheyi, is designed to ensure that there is zero distance between the company and its customers. After removing an entire layer of middle managers—some 12,000 employees—Haier distributed power to entrepreneurial local leaders of a large number of newly-created, semiautonomous, customer-facing fractal business units, or “microenterprises,” all of which are connected through a common digital

These leaders are entrusted with the power to make critical business choices, hire (and fire) team members, allocate resources, and decide levels of compensation. Just as importantly, they are tasked with ensuring compliance with the growing number of local and global regulations. Today, Haier describes itself as a “self-organizing, self-driven, and self-evolving ecosystem enterprise,” with the teams empowered to go wherever the growth opportunities present themselves.

Different companies will make different choices on the right balance, from the selective decentralization of P&G to the radical decentralization of Haier. But given the ongoing geopolitical fragmentation and the increasing competitiveness of fast-moving markets, companies will have to move toward the edge—one way or the other.

From Two-Way Data to a Multidirectional Flow. The fractal company relies on what one business leader described as the “democratization of data”: the real-time, transparent, multidirectional flow of data and information inside and outside the company. This transparency becomes even more critical as the pressure of regulatory compliance, which can vary across countries, grows. Accordingly, companies must design their digital infrastructures—specifically their information management systems—to achieve this data democratization. In doing so, they must also overcome the pervasive “keep data confidential” mindset common to most scale-driven hierarchical companies.

The fractal company relies on the “democratization of data.”

Schneider, the global leader in automation and energy solutions, has set up an internal team—with senior oversight and aggressive timelines—to migrate to a future-ready fractal data model. Such a model needs to meet multiple (and sometimes conflicting) requirements. It should be responsive to a world in which “data is becoming a geopolitical asset and a strategic differentiator,” as Hervé Coureil, the company’s chief governance officer and secretary general, puts it, but where global teaming and local, high-speed decision making mean that transparent data sharing is more critical than ever.

With these factors in mind, Schneider has built a global network of data offices based on fractal design principles, with linkages to both its central team and local offices. At its most mature level, a fractal information management system should:

- Collect, clean, and store the enormous amount of data generated by the company’s products or services.

- Share this data across the company (subject to confidentiality regulations) so that every employee—wherever they may be—can access the information to make fast and effective decisions.

- Document and facilitate the management of the ideas, insights, and other types of “knowledge” that is generated by team activities.

- Support the cocreation of new products and services through digital tools that make it easier for employees to collaborate with each other, with customers, and with external partners.

- Support a culture of company-wide alignment and individual team autonomy through the implementation of a digitized performance management system.

As Coureil says, “building such a company-wide capability to turn the data into value for customers or insights for the company creates a cycle of data-driven value-creation for the organization and its ecosystem.” Typically, incumbents have been wary to move fast on democratizing data, due to the entrenched culture of top-down control and confidentiality. But building such a digital and information management system underpins the success of all other design dimensions.

From Contractual Agreements to Digital Trust. Consumers will engage in online transactions only if they trust the e-commerce platform involved as well as the payment gateway, the broader network of suppliers, and the last-mile delivery system. With more and more transactions happening online—interactions within a firm or with external entities and communities—the fractal company has to build trust very differently than traditional companies. The two parties involved in a given transaction might never meet physically, after all; there is also a growing business imperative to share information as opposed to keeping it confidential. Both of these developments can lead to an inherent mistrust, which in turn can lead to fluid corporate and customer relationships unless the issue is actively addressed. In a 2021 survey by the BCG Henderson Institute , trust was found to be “a proximate factor—albeit not necessarily the root cause—in the failure of 57 of the 110 unsuccessful ecosystems” studied.

Fractal companies focus on “systemic trust” in the broader business network.

Instead of relying on ponderous trust-enforcing measures developed for the predigital era (such as codes of conduct for employees, company-wide regulations, and legally binding contracts with external partners) the fractal company must proactively embed digital trust into its operations. It can no longer be assumed that trust will develop spontaneously through ever closer cooperation between the parties involved; relationships are more fleeting in an online environment, especially as consumer distrust of companies has grown. Fractal companies approach this problem by switching their focus from “relationship trust” (in other words, the contract-based trust between the company and its partners and customers) to a focus on “systemic trust” in the broader business network.

Marco Aguiar, a BCG managing director and senior partner and an expert on the subject of building digital trust, notes that companies have to actively “design for trust” by embedding a range of tools as part of their core operations—not only traditional tools such as contracts but also newer ones such as blockchain and a set of “trust and verify” technologies. (The promise of money back if the product or service purchased online was not satisfactory, for example, or the transparent posting of customer

Redefining Scale in Fractal

“Scale still matters, a lot,” as the leader of a global industrial company told us, “but in a different definition than in the past: network scale beats ‘traditional value chain’ scale. Local scale is often more important than global scale.” A fractal company applies this new definition to redesign global processes, capabilities, data, and even software for local advantage.

They do this through the concept of “componentization,” which was first applied to software development. Instead of being globally integrated, a company’s processes and its underlying data structure can be designed as an aggregation of components. Some of these components (typically 60% to 70%) are necessarily global to provide scale advantage; these are managed from the center. Other components are designed to allow regional and local teams to customize processes to their specific markets through an application programming interface (API).

Take the increasingly critical digital marketing process. It could be designed as an end-to-end integrated process centrally deployed across all the markets—cost efficient but with no customization for local needs. Or it could be highly fragmented, with each market deploying its own process—but with no global scale benefit. The fractal approach is to “architect” the digital marketing process with global components and APIs for use by local teams and partners, which can customize them to local needs and regulations. Careful design and appropriate governance are essential to making this approach work, as is a strong feedback loop—and in fast-changing markets it can be the difference between winning and losing.

In such a design, the advantage shifts from the global scale curve of an integrated process to leveraging the power of the experience curve, in which replicability and reuse of the components involved can reduce costs and improve performance. As a business leader tasked with building a fractal organization told us, “such process-architecting skills will be one of the most critical jobs” in fractal companies.

Developing Multifocal Leadership

But how does one lead an organization designed for fractal advantage? The head of a global consumer company’s HR division gave a glimpse of the answer when he told us that every leader—at the center and at the periphery—has to be able to “not just play the game well” (in other words, execute the company’s strategy) but also “be able to improve the game they play (in other words, innovate at speed based on new market opportunities and changing customer needs) by harnessing capabilities from across the firm.” As such, they must be what we call “multifocal,” and therefore quite different from the majority of leaders in scale-driven companies, who focus primarily on (and are rewarded for) efficient execution.

Companies should develop a performance management system that measures and rewards multifocal leadership in two important ways. First, it should go beyond the quantitative metrics relating to efficiency, revenue, and profit that tend to predominate in scale-driven companies to include other quantitative metrics for measuring speed (such as speed to market or the growth of new revenue pools) as well as qualitative metrics for measuring local innovation, responsiveness, and

Second, to promote collaboration across different parts of the company, it is important to build interlinked metrics with other roles and teams. Haier, for example, measures the performance of employees in central support-services roles (such as finance, human resources, and IT) based on their success in serving the microenterprises at the edge of the business.

Preparing this new generation of executives and ensuring that they have the necessary multifocal leadership skills is not easy—especially if they have come up in a culture of top-down decision-making, as most have. As a top executive at a company struggling with this organizational transition told us, companies need their most senior and successful multifocal managers to be role models and “actively mentor these fractal leaders and their teams, attend their leadership meetings, and refine their agenda so that they learn to focus not only on efficiency but also on innovation , speed to market, and customer responsiveness.”

How to Start Building a Fractal Company

Fractal advantage is all about unlocking growth in a fragmented world. BajajFinServ, the diversified nonbanking financial services firm in India, has grown in 15 years to become a $35 billion market-cap company by applying fractal design principles even in a local market context. This remarkable success is built upon the motto “break to grow.” They quickly set up fractal teams with complete ownership to drive growth for every new micromarket opportunity or adjacent business—or even for building out new capabilities. They exploit scale of processes and capabilities by designing them as components which operate at different levels of market aggregation. This fractal structure is supported by an interlocking performance management system which measures and incentivizes each team to collaborate with others.

For incumbent CEOs, the big question is how to bring all these different fractal elements together. What path should they follow on this journey of transformation, and what should be their first move be? We have four pieces of advice:

1. Make sure that senior leadership is laser focused on profitable growth. Such clarity makes it easier to make some of the fundamental organizational tradeoffs necessary to move to the right position in the scale-fractal continuum, rather than merely striking a compromise between the two approaches.

2. Don’t try to design a complex fractal company and launch a complete shake-up of the organization all at once. Instead, choose one of these four paths:

- Deploy fractal design principles when launching a new “edge” business, as John Deere has done in building its fast-growing digital solutions business.

- Choose a few of the design principles and apply them selectively to the whole organization. This is the path Natura has taken, creating a lattice structure with crisscrossing links to weaken the hierarchical boundaries of the matrix management system.

- Apply fractal design principles in markets where the business faces the biggest disruption from the forces of fragmentation and local competition, as P&G has done.

- The fourth, and perhaps the most radical, pathway is the one Haier has taken, building the entire company from the ground up by creating fractal autonomous units serviced by global functional teams.

3. While focusing on one of the four pathways above will certainly bring benefits, the full potential of fractal organization to unlock sustained profitable growth will be achieved only if all its interlocking elements—the design principles and the redefined scaled processes and capabilities—come together in an integrated organization led by multifocal leaders.

4. Finally, remember that your company is not the only one trying to make this change. Every global firm is struggling with these choices. Winning advantage will come from moving proactively to the advantaged fractal design—before being forced to do so by activist shareholders or competitor moves.

The decision of where and how to start will depend on a number of factors—including a company’s starting position, its status as an asset-heavy or asset-light business, the nature of its products and services, the intensity of its competition, and the level of technology-led disruption in the industry. But there is no alternative to building a company with fractal characteristics. As Kevin Nolan, the CEO of GE Appliances (now a Haier subsidiary) said in an interview with the Financial Times, “corporations want completely simple, [whereas] individuals want totally custom.…[t]hat, I think, is what successful companies in the future are going to have to figure

The design principles and potential pathways laid out in this article can help leaders make this tradeoff. While there is no “right” way to get started, there is a wrong way—and that is not to get started at all. If CEOs delay, they will be putting the very existence of their companies at risk. But those who can successfully transform their scale-driven businesses into fractal-advantaged businesses will have prepared them for lasting success in an increasingly fragmented world.