Chip shortages and pandemic factory lockdowns have dominated headlines in the automotive industry around the world for several turbulent years. Less noticed has been a wave of disruption that is transforming another part of the industry—the retail sector. The impact of this disruption will be felt throughout the automotive ecosystem.

Chronic supply shortages of new vehicles, the transition from internal combustion engines (ICEs) to electric vehicles (EVs), and the emergence of new digital retail business models are all radically changing the ways vehicles are being brought to market. Moreover, they are occurring at a time of mounting concerns that much of the global economy may be heading into recession.

The implications are enormous for brick-and-mortar dealerships. Business models that have traditionally revolved around having ample stocks of cars on their lots and conducting business primarily in physical showrooms will have to adapt to supply scarcity. Companies will have to begin engaging with car buyers online. And because EVs require fewer repairs and less servicing, dealers will also have to develop new revenue streams. Dealerships that learn to skillfully navigate this new go-to-market landscape will emerge as the winners in the years ahead.

Our research found that US dealers are confident they will successfully navigate this transformation. They believe that brick-and mortar dealerships will remain the primary channels for purchasing vehicles. They also believe that neither new EV OEMs nor digital marketplaces selling directly to consumers will pose serious competitive threats or undermine their business models.

We also found, however, that many US dealers may not be adequately preparing for the challenges ahead. They are taking some steps in the right direction, such as by building new digital capabilities to engage with customers outside of showrooms and investing in training and new equipment to support EVs. But dealers are underestimating the speed of the transition to EVs. And many aren’t making the really big digital push needed to successfully compete with the new players.

The Supply Crunch and Inflation Will Linger

To get a sense of how structural changes in automotive retail are playing out around the world, Boston Consulting Group conducted research in major markets during the past year. This article focuses on the US, but the trends we observed, and their implications, are similar in other markets.

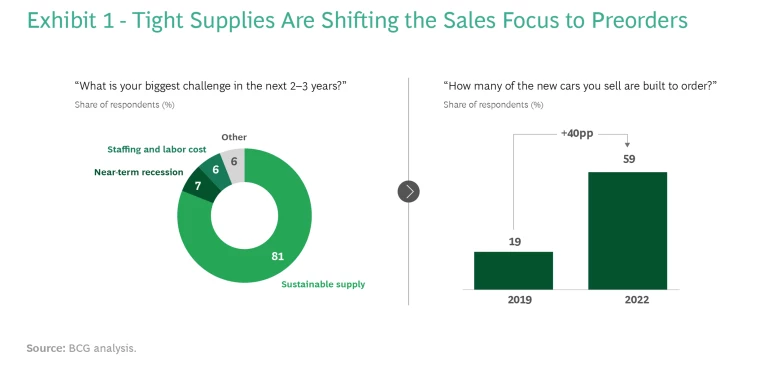

Looking ahead, 81% of dealers see inventory shortages as their most serious challenge for the next two to three years.

We surveyed more than 350 US auto dealers, ranging from small, independent outlets to large franchisees. We asked about their outlook for the US auto market; how supply constraints, digital retailing, and the EV shift are affecting their businesses; and how they’re preparing to meet these challenges. We also surveyed more than 550 consumers who had recently purchased a vehicle. This research, combined with our work on more than 500 automotive cases with clients over the past few years, provides a unique perspective on how the industry is evolving.

Looking ahead, 81% of dealers see inventory shortages as their most serious challenge for the next two to three years. The expectation that OEMs won’t be able to manufacture enough light vehicles to meet strong US demand is supported by BCG research. In 2021, we estimated that around 10 million vehicles globally were not produced and sold because of the semiconductor shortage. This has reset expectations in the auto industry. We project at least 9 million such lost sales in 2022 and that supply and demand won’t return to balance until 2024.

What’s more, dealers report that 59% of the new cars they sell are now built to order—as opposed to just 19% in 2019. (See Exhibit 1.) If this trend holds, it will constitute a retail paradigm shift. Traditionally, US buyers would drive their cars home off the lot after purchasing them in showrooms. Due to inventory shortages, however, buyers now often must wait months before OEMs can fill their orders. That means more time to customize vehicles—and opportunities for US dealers to make higher margins by adding and upselling features. It also means that dealers can charge at or above the manufacturers’ suggested retail prices rather than offer discounts for inventory sitting on the lot.

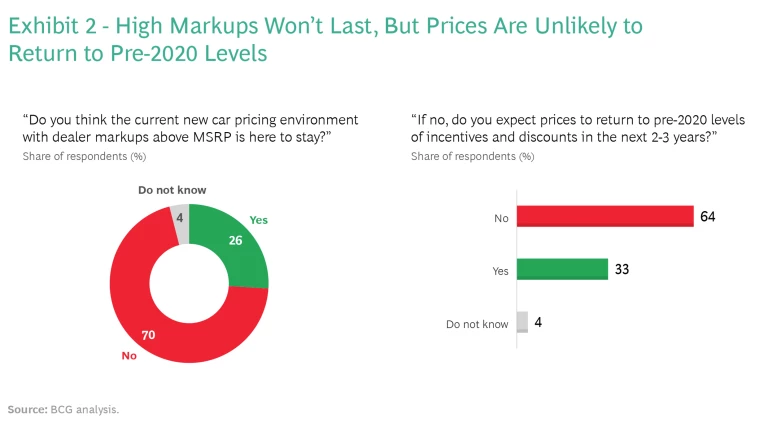

Seventy percent of dealers also believe that the current pricing environment, in which dealers have been able to mark up prices above the manufacturer’s suggested retail price, won’t last. That’s partly due to recession fears as well as the fact that OEMs have been demanding that dealers stop such practices—and are increasing prices themselves to offset rising costs and boost profits. Still, nearly two-thirds of dealers don’t expect prices to return to pre-2020 levels, when sizable incentives and discounts were common, for at least two or three years. (See Exhibit 2.)

Preparing for the EV Age

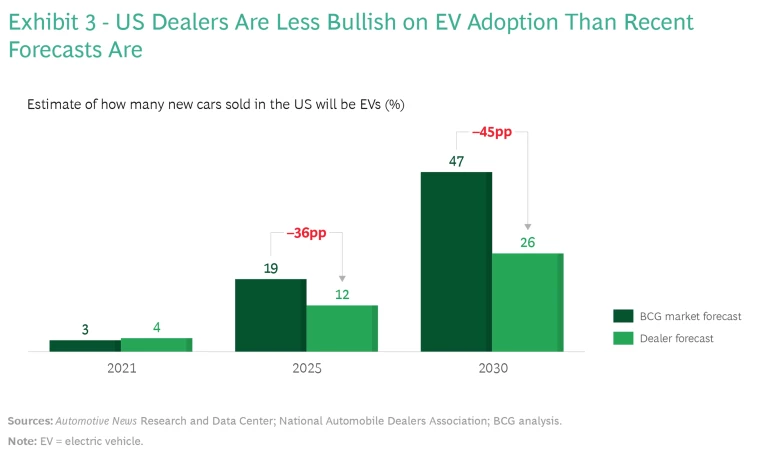

In BCG’s 2022 report on electric cars , we forecast that EVs will account for 19% of light vehicles sold globally by 2025 and for 47% by 2030. In fact, BCG has revised its annual forecasts for EV adoption upward over the past few years because OEMs have increased their commitments to EV production capacity and accelerated the timetables for phasing out ICEs.

But our study found that US dealers may be underprepared for the EV age. Dealers said they expect that vehicles powered entirely by rechargeable batteries will account for only 12% of light-vehicle sales in 2025 and 26% in 2030—about half of what we project.

Our study found that US dealers may be underprepared for the EV age.

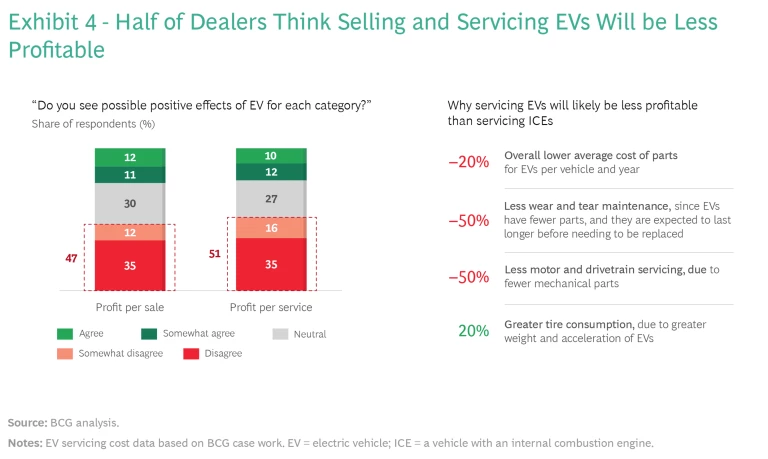

Maintenance and service currently are major sources of revenue for dealerships. But the fact that EVs require less maintenance than ICEs will significantly affect their business model. Dealers recognize this challenge. Forty-seven percent of respondents indicated that they expect EVs to have a negative impact on profits per sale; 51% think servicing of EVs will be less profitable. These sentiments also align with BCG research. Although EV tires will likely need to be replaced more frequently, due to the vehicles’ heavier weight and faster acceleration, EVs have far fewer mechanical parts than ICEs. Those parts also last longer on average before they need to be replaced. EVs require only about half as much maintenance due to wear and tear and servicing of the motor and drivetrain, for example. We forecast that annual parts costs for EVs will be about 20% lower than those for comparable ICE vehicles.

The shift to EVs is also likely to put further pressure on the margins of brick-and-mortar dealerships, accelerating consolidation in the retail sector as scale becomes more critical. OEMs are asking dealers to make sizable investments to support EVs. Ford, for example, recently announced that it expects dealers to add infrastructure, such as charging stations, and employ digital commerce if they are to sell its EVs. General Motors (GM) is taking similar measures with its Cadillac franchisees, while its Buick division is going so far as to buy out dealers unwilling to invest in EVs.

Many smaller dealers—those with fewer than five locations, or “rooftops”—will be hard-pressed to make such investments in addition to coping with declining repair revenue. Many appear to acknowledge the new realities: about one in 25 dealers in our study indicated that they are considering selling out to a larger dealer group within the next three years. Indeed, BCG forecasts that the number of dealer rooftops in the US will shrink by 14%—to around 14,300—by 2034.

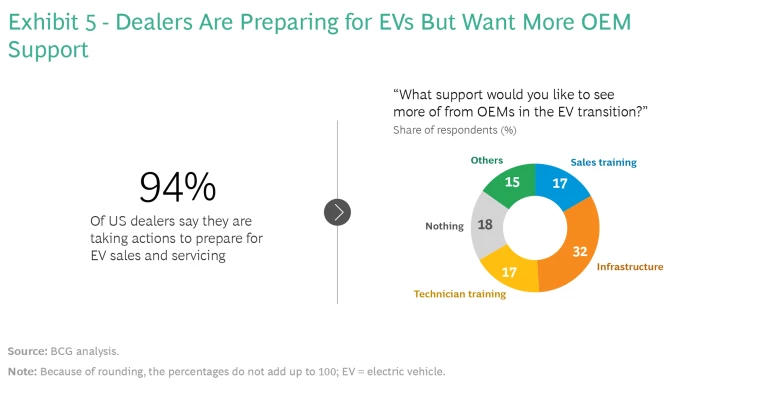

Ninety-four percent of dealers said that they are getting ready to sell and service more EVs. The most frequently cited preparations, however, consist of EV training programs for salespeople and certification programs for the mechanics who will need to maintain batteries and electric drivetrains. While necessary, such measures alone won’t be sufficient to prepare dealers for the EV age. Eighty-two percent of franchised dealers also reported that they need more support from automotive OEMs. The biggest need, cited by around one-third of respondents, was for help with EV infrastructure. These responses suggest that dealers are investing in areas that don’t require much cash and that they may be relying on support from OEMs for more expensive EV needs, such as calibration tools and fast-charging equipment.

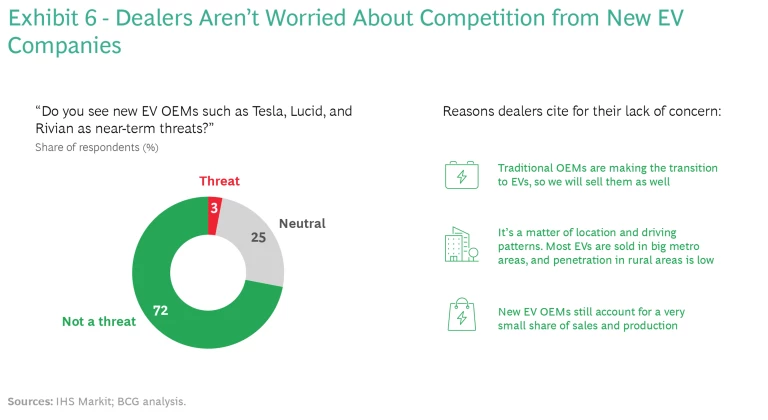

Despite this inconsistency, US dealers are confident that they will be competitive with pure-play EV companies. Only 3% of dealers surveyed said that they view companies such as Tesla, Rivian, and Lucid as imminent threats to their businesses. Seventy-two percent stated that these new competitors are not a threat; the remainder were neutral. (See Exhibits 3 through 6 in the carousel below.)

In addition to their skepticism over EV adoption, dealers cited several reasons for their lack of concern. Many noted that they will also be selling EVs: traditional OEMs are making the shift from ICEs and are selling EVs through their traditional channels. (In the US, most states require traditional OEMs to sell through their existing dealers, while new EV OEMs, such as Tesla, are able to sell directly to consumers in many states.) Dealers also observed that pure-play EV companies have limited geographic reach, particularly in rural areas, where many consumers worry about the driving ranges of battery-powered vehicles.

Embracing Digital Retail

Digital commerce has also been silently transforming auto retail. Only around 0.5% of new car sales in the US were transacted fully online in 2020. But if automotive e-commerce follows an adoption curve similar to that of other consumer durables, such as appliances and furniture, online sales transactions will likely reach 11% to 17% by 2030 and 21% to 33% by 2035.

Although the entire auto purchase process may be slow to move online, digital channels are already playing a critical role. A BCG survey of US consumers found that more than 80% of car buyers do research online before visiting a dealership. They turn to traditional offline information sources—such as family and friends and specialty magazines—much less frequently than they used to. The typical buyer also visits fewer dealerships before making a purchase—just 1.4 on average, compared with nearly 4 just a few years ago. Buyers are more informed and know the vehicle specifications they want before going to a dealership. This is particularly true for EV buyers.

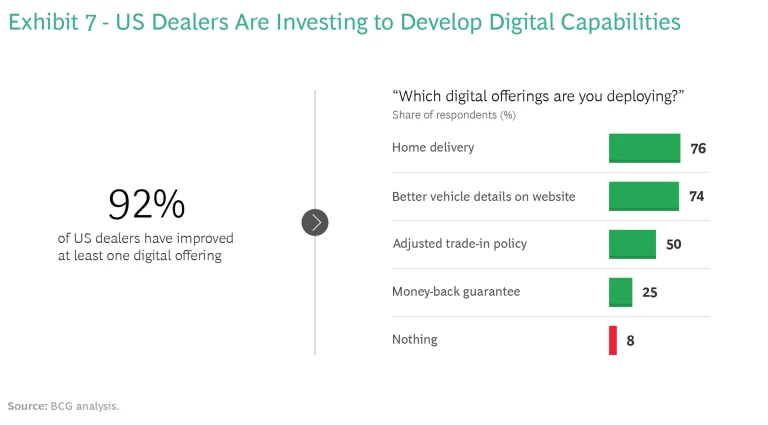

Dealers are expanding their digital capabilities in response to this shift in consumer behavior. Ninety-two percent reported that they have improved at least one digital offering. Around three-quarters now enable buyers to book online for the home delivery of the vehicles they purchase, for example, and provide better vehicle descriptions and imagery on their websites. (See Exhibits 7 through 9 in the carousel below.)

OEMs are stepping in as well, introducing digital services that enable customers to make fewer or shorter visits to dealerships. Genesis, the luxury arm of Hyundai, has launched the Genesis Concierge service, for instance; Ford has launched FordPass App; and Nissan offers Nissan@Home. Among other things, such services offer home delivery of cars for test drives, the ability to buy vehicles from home, online maintenance scheduling, and loyalty programs.

Dealerships also face growing competition from digital dealers, such as Carvana and Vroom, that sell directly to consumers. But 88% of US dealers said that they don’t consider digital retailers a competitive threat, either imminently or in the medium term. They may have a point: as digital leaders gain scale, several of them have been beset by falling profit margins, consumer complaints, and administrative snags, such as long delays in processing titles and registrations. They have also struggled to gain access to inventory—a challenge that prompted Carvana to acquire the auto auction company ADESA. Financial markets have also turned negative: while the stocks of listed dealership chains, such as Penske and AutoNation.com, have significantly outpaced the S&P 500 Index since late 2020, the shares of listed digital retailers have underperformed.

The digital offerings of brick-and-mortar dealers are still far from the end-to-end customer experience offered by online digital retailers. But we are starting to see dealers strengthen their digital reach by forging partnerships with online marketplaces and technology providers. GM has introduced CarBravo, an online platform with an expansive inventory of used vehicles both from dealerships and a national central stock. CarGurus’ Digital Deal enables dealers to sell more vehicles by providing access to online shoppers through its retail platform. The car retail platform Roadster, which was acquired in 2021 by CDK Global, is one of the growing number of companies providing a digital retail experience for brick-and-mortar dealers.

Digitally enabled brick-and-mortar dealerships have an advantage over their purely digital counterparts in terms of customer acquisition, the selection and value they offer customers, and distribution.

By supplementing the traditional strengths of brick-and-mortar dealerships, such partnerships help create “enabled” dealers that should become very competitive with digital dealers. According to our analysis, digitally enabled brick-and-mortar dealerships have an advantage over their purely digital counterparts in terms of customer acquisition, the selection and value they offer customers, and distribution. Digitally enabled dealers can also provide an omnichannel experience that allows customers to shop at the showroom, online, or both.

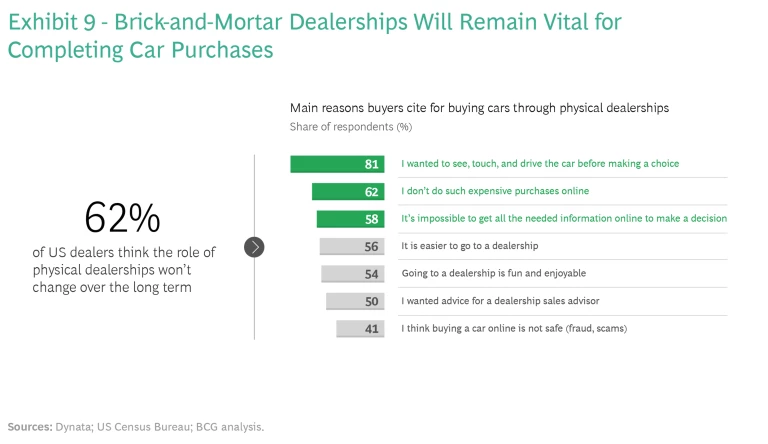

Despite the many forces of disruption roiling the industry, most US dealers foresee the brick-and-mortar showroom remaining the cornerstone of light-vehicle retail. Sixty-two percent told us that they doubt the role of physical dealerships will drastically change over the long term. Most consumers seem to agree. Eighty-one percent of recent car buyers surveyed said that they still prefer going to a dealer to see, touch, hear, and drive vehicles before buying them. A majority of consumers also indicated an unwillingness to make such expensive purchases online and believe they would be unable to get all the information they need to make a decision.

Subscribe to our Industrial Goods E-Alert.

The Implications for Players in Auto Retail

The emerging automotive retail environment has different implications for various players in the ecosystem. We see the following imperatives for success:

- Dealers. To succeed in the digital age, dealerships need compelling omnichannel offerings that combine online showrooms with their brick-and-mortar counterparts. Dealers should build win-win partnerships with e-commerce marketplaces. They should reduce friction along the customer journey—such as paperwork required for registration, negotiations over financing, and the process for trade-ins—prior to handing over the keys. Dealerships should also look to monetize their service loaner fleets, such as by introducing subscription business models or short-term rentals.

- Digital Marketplaces and Solution Providers. Rather than view conventional dealerships as competitors, digital players should look for opportunities to strengthen their relationships with them by enabling dealers to leverage their online experience to create customer value. They should also scale up their own solutions for acquiring inventory, such as with consumer-to-dealer or dealer-to-dealer transaction platforms. Digital players can also provide transaction analytics and other market-intelligence services.

- OEMs. Automakers should double down on programs designed to prepare dealers for the transition from ICEs to EVs. They should rethink their approaches to dealer profit margins and bonus programs, especially as the build-to-order trend grows and maintenance and servicing revenue change. OEMs should collaborate with dealers to help create seamless customer journeys that combine online with offline engagement and consider new ways to manage and monetize inventories of off-lease vehicles.

The COVID-19 pandemic altered the way people work and buy daily necessities. In much the same way, stock shortages, the rise of digital dealers, and the transition to EVs are transforming how cars are bought and sold. The winners in the auto retail landscape of the future will be the dealers, online marketplaces, and OEMs that best combine the traditional advantages of the showroom with innovative digital solutions to create a seamless customer experience.