This is the first in a series of articles on how governments and businesses in developed and developing countries can collaborate to solve some of the toughest challenges facing society.

Governments and companies must find new ways to collaborate if they are to solve the big multigenerational challenges, such as poverty, inequality, and climate change.

Rwanda is Africa’s most densely populated nation, with 13 million people living in a landlocked country that is smaller than Switzerland. Nevertheless, the agriculture sector accounts for more than one quarter of the country’s GDP, and some 70% of Rwandans participate in the farming business. As such, agriculture is viewed as central to the future of the country. “Its value goes beyond providing our basic human need for food,” says Agnes Kalibata, a former Rwandan agriculture minister. “It grows our economies and, more importantly, it changes society.”1

For this reason, the Rwandan government invests heavily in the agriculture sector. But until recently, the investment did not have the hoped-for impact because of a lack of collaboration and coordination among the agricultural ministry, companies, and farmers. Things started to improve five years ago, when the government launched the Smart Nkunganire System (SNS), a public-private partnership (PPP) between the Rwanda Agriculture and Animal Resources Development Board and BK Techouse, a subsidiary of the BK Group, the country’s largest commercial bank.

The initial product of this alliance was a digital supply chain management platform that gave farmers better access to the country’s agricultural inputs subsidy program, which provides seeds, fertilizers, pesticides, farming machinery, and other inputs for a reduced price. The hope was that this would increase the productivity of Rwanda’s 1.2 million smallholder farmers.2

Shortly after its launch, however, the PPP evolved into something we call a public-private ecosystem (PPE), which we define as a dynamic network comprising a government or other public body and an evolving and ever-changing group of largely independent economic participants. The government invited more than 1,000 small agriculture dealerships, along with some 30 small fertilizer and seed companies, to join the digital platform .

Since then, the ecosystem has expanded even further, and it now also connects farmers and participating companies with banks and other providers of financial services. For example, the Bank of Kigali has created a universal digital wallet called IKOFI designed to provide farmers with a pathway to financial inclusion. Already, more than 250,000 farmers have registered for the service.3 In the future, the ecosystem may become a one-stop shop where farmers can access a wide range of services that boost their—and, ultimately, Rwanda’s—fortunes.4

Governments need to tap the expertise of business leaders by engaging with them in a collaborative, creative, nontraditional way.

By bringing different sections of society together, Rwanda’s SNS powerfully demonstrates just how far the country has come in recent years. And we think that PPEs can serve as a model for all governments and businesses—in developed and developing countries—as they try to solve some of today’s great societal problems. Food scarcity, poverty, unemployment and underemployment, inequality, environmental pollution, and climate change—these and other challenges are just too big for governments to solve on their own. In our view, they need to tap the expertise of business leaders by engaging with them in a collaborative, creative, nontraditional way.

Governments Need to Rethink How They Engage with the Private Sector

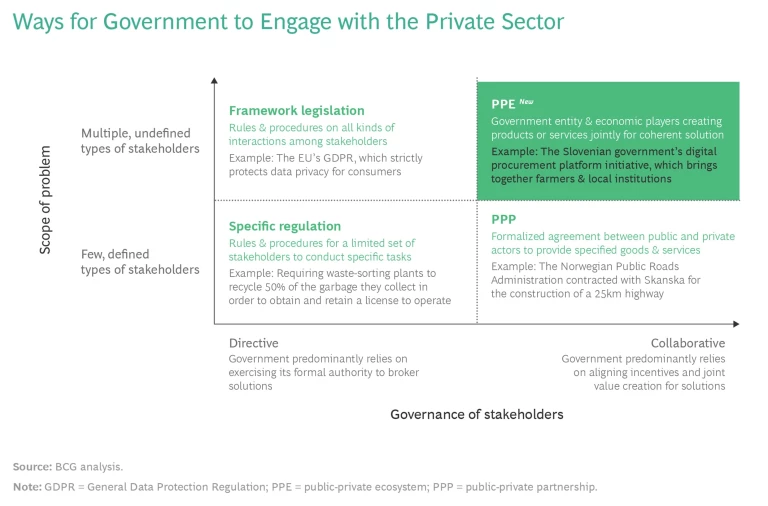

Traditionally, governments have engaged with the private sector in three main ways. (See the exhibit.) One is through specific regulation, by issuing decrees—official orders with the force of law that are directed toward companies within a single industry. In Germany, for example, waste disposal companies are required to recycle 50% of the garbage they collect in order to win and retain a license to operate.

Another way is through framework legislation—by imposing rules, through general regulation or legislation, on a broad set of companies. Across Europe, for example, the General Data Protection Regulation imposes strict rules on how all companies can collect and use the personal data of millions of citizens.

A third way governments engage with the private sector is through PPPs, where a government invites one or more companies to collaborate on a specific project. Before evolving into a PPE, the Rwandan SNS was a classic PPP.

These traditional ways of engaging with the private sector have their strengths. Top-down and directive legislation offers efficient and effective ways for government to tackle defined problems with specific solutions. By contrast, PPPs are effective for solving problems with clearly defined solutions because they help governments and businesses resolve questions relating to risk, capital, and the lack of capabilities and resources.

But traditional ways of engaging with the private sector have their limitations, too. If they are strictly enforced (as they usually are), specific and framework legislation can have unintended consequences: companies pursuing their own self-interest may choose to follow the letter of the law but not, necessarily, the spirit of the law. Similarly, if PPPs are struck among a small number of companies (as they usually are), they become a kind of closed shop, and the opportunity to find the very best solution may be lost. Also, if the scope of PPPs is defined within a fixed and limited contractual framework (as it usually is), then their innovative potential may be reduced even further: PPPs have a reputation for delivering efficiency rather than sparking creative solutions.

PPEs put companies on an equal footing with governments, and they create a collaborative space where the energy and entrepreneurial ingenuity needed to solve society’s biggest problems can run free.

Fortunately, there is a fourth way: public-private ecosystems. Designed well, they can overcome some of the limitations of the traditional ways of engaging with the private sector. They put companies on an equal footing with governments (in fact, some PPEs are orchestrated by companies rather than by governments) and they create a collaborative space where the energy and entrepreneurial ingenuity needed to solve society’s biggest problems can run free.

The Transformative Potential of PPEs

Originally, the word “ecosystem,” as coined by the British botanist Arthur Tansley in the 1930s, described a community of organisms in the natural world that collaborate and compete with one another, evolve together, adapt to new challenges, and exploit new opportunities. The word was first applied to the business world by James Moore, a strategist, in the early 1990s.5 Since then, driven by the enormous success of tech firms and thousands of startups building their businesses according to this model, the concept has developed into a distinct discipline within the realm of business strategy. At BCG Henderson Institute, we have been exploring the subject for the past several years in a series of publications offering practical guidance on the topic to business leaders.

Business ecosystems —including Amazon’s marketplace, Apple’s iOS, and Meta’s Facebook—are able to facilitate the creation of highly modular solutions. This is because they offer four critical benefits: access to a broad range of capabilities, the ability to scale quickly, significant flexibility, and great resilience.

The business ecosystems created by the Big Tech companies demonstrate the transformative potential of the model. And they can serve as good blueprints for governments that want to work out how best to engage with business in order to tackle some of the biggest social, political, economic, and other public problems. As uniquely collaborative environments, business ecosystems offer participants the space to create products or services that together constitute new solutions to those challenges.

PPEs can help solve the problem of insufficient scale on the demand side and the supply side—for example, by supporting local farmers in aggregating their produce and matching it to larger resellers. They can also foster collaboration across sectors by establishing trust and facilitating coordination. And they can help overcome co-innovation challenges by encouraging various participants to innovate simultaneously and by providing a platform for effective coordination.

PPEs Have Already Helped Solve Big Societal Problems

Currently, PPEs remain an underused way for governments to collaborate with the private sector. Nevertheless, there are some good examples for governments to consider in addition to the Rwandan government’s SNS.

One example is the Slovenian digital procurement platform initiative that links farmers with schools and other public institutions. The goal for the digital platform was twofold: to improve the nutrition of school children and public-sector workers and to improve access to the local produce of Slovenian farms. Within four months of its launch, the platform had registered 114 farmers, food producers, and cooperatives, along with 754 public institutions; and it had made available for purchase more than 2,200 locally farmed products. The effort was a great success: some 60% of schools increased their consumption of local produce. Since then, the platform has become a fully-fledged ecosystem.

Another example is the so-called digital sandbox ecosystem established by the City of London and the Financial Conduct Authority in the UK. Providing innovative companies with a digital testing environment, this ecosystem was initially launched to encourage them to come up with solutions to problems caused by COVID-19. In the first 11-week pilot, some 94 companies applied to join the ecosystem, and 28 were selected to participate. They were offered specific data to help them solve three problems:

- Detecting and preventing fraud and scams amid a sharp rise in phishing emails

- Supporting vulnerable citizens, especially older people who were more susceptible to COVID-19 and who found it difficult to perform basic financial activities

- Improving access to finance for the small and midsize companies that were hardest hit by the economic downturn resulting from widespread lockdowns

The results were encouraging: the sandbox ecosystem accelerated product development times for some 84% of participants, led to improvements in the design of financial products, and helped companies refine their early-stage business models . One product in particular, which is still in the developmental stage, shows great promise: it gives unbanked people, such as the homeless, easier access to benefit payments.

But unquestionably, the best-known PPEs are those orchestrated by the various advanced research project agencies of the US government. The most famous of these is the Defense Advanced Research Project Agency (DARPA), which is responsible for creating breakthrough technologies and capabilities for national security. Since its founding in 1958, DARPA has orchestrated an ecosystem of innovators—including companies, universities, and government bodies—that normally compete against one another. It has also invested in fundamental research that led to the invention of the internet, the personal computer, GPS, drones, and Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine.

In other words, DARPA has, as The Economist noted, “shaped the modern world.”6

Politicians, policymakers, and other government decision makers face a daunting task: to find solutions to massive, multigenerational problems that will improve the lives and livelihoods of their citizens. That job was tough enough before the pandemic; now, it is doubly difficult. What should they do?

To solve these problems, governments should look to tap the expertise, ingenuity, and resources of the private sector by engaging with companies in public-private ecosystems. Similarly, companies should try using this collaborative approach to increase the leverage of their own social impact and sustainability initiatives.

By working together in this way, governments and companies may not only solve immediate societal problems but also change society—or even, as DARPA has done, shape the world.

Notes

1. Agnes Kalibata, “Agriculture Is the Key to a Prosperous Africa,” Financial Times, December 6, 2017, https://www.ft.com/content/7b8a97ea-d9d7-11e7-a039-c64b1c09b482.

2. “Smart Nkunganire System to Enhance Access to Agriculture Inputs,” Rwanda Ministry of Agriculture and Animal Resources website, accessed on December 06, 2021, https://www.minagri.gov.rw/updates/news-details/smart-nkunganire-system-to-enhance-access-to-agriculture-inputs.

3. GSM Association, Digital Agriculture Maps: 2020 State of the Sector in Low and Middle-Income Countries, September 2020, p. 49, https://www.gsma.com/r/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/GSMA-Agritech-Digital-Agriculture-Maps.pdf.

4. “BKTechouse Partners with Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to Enhance ‘Smart Nkunganire System’,” IGIHE, March 4, 2021, https://en.igihe.com/news/article/bktechouse-partners-with-bill-melinda-gates-foundation-to-enhance-smart.

5. James F. Moore, “Predators and Prey: A New Ecology of Competition,” Harvard Business Review, May–June 1993, https://hbr.org/1993/05/predators-and-prey-a-new-ecology-of-competition.

6. “A Growing Number of Governments Hope to Clone America’s DARPA,” The Economist, June 5, 2021, https://www.economist.com/science-and-technology/2021/06/03/a-growing-number-of-governments-hope-to-clone-americas-darpa.