More companies are forging strategic alliances as they seek competitive advantage. Here’s what they must do to build and manage them successfully.

The development and deployment of COVID-19 vaccines in less than a year was a stunning achievement for science. But it also illustrated the power of a particular kind of partnership: the strategic alliance.

Strategic alliances brought together biotech ventures with revolutionary vaccine technologies. They united pharmaceutical giants with the capabilities and infrastructure required to successfully speed the drugs through clinical trials and regulatory approval and into mass production and distribution. And the partnerships, which produced the Pfizer-BioNtech, Moderna, and AstraZeneca-Oxford vaccines, were executed with impressive efficiency.

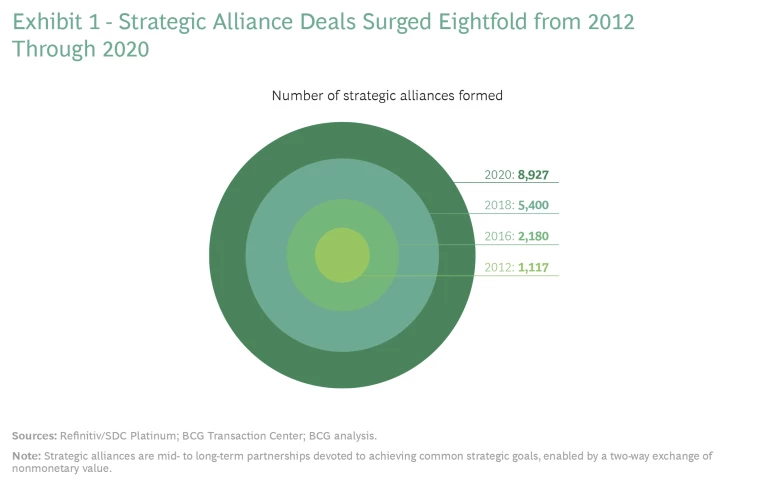

The speedy development of COVID-19 vaccines illustrates why the number of strategic alliances has grown dramatically in recent years. (See Exhibit 1.) Companies in sectors as diverse as health care, transportation equipment, and discretionary consumer products are scrambling for competitive advantage in an era of swift, disruptive technological change on multiple fronts. And they’re finding that strategic partnerships offer one of the best ways to meet the crushing need to innovate, scale up, and get to market.

Building and managing a successful collaboration isn’t easy, however. Indeed, a high percentage of strategic alliances fail. That’s a risk many companies can no longer afford. In today’s rapidly transforming business landscape, investing six months to a year in an unproductive effort to jointly develop a cutting-edge mobility, industrial Internet of Things (IOT) , blockchain , or remote health care-delivery solution, for example, can translate into big missed opportunities and a loss of market share.

Why More Companies Are Choosing Alliances

Strategic alliances are medium- to long-term partnerships in which each participant contributes nonmonetary assets to achieve a joint goal. The core advantage of strategic alliances is that they can enable deeper collaboration and higher agility than other forms of partnerships. Alliances are typically preferable to straightforward transactional contracts when both parties share a strategic goal, need more than a short-term collaboration, and aren’t certain of the outcome. They are also much easier to establish and dissolve than joint ventures , mergers, and acquisitions and require less commitment. Alliances enable narrower, more-focused collaborations. For example, the two companies can collaborate on a single product line. And they don’t require a merger with or acquisition of the entire company in order to create synergy. Alliances can also take on more experimental projects that move partners into unknown territory.

In fact, alliances are often a means for two companies to test the waters with each other before committing to a joint venture. The strategic alliance Sony and Panasonic formed in 2013 is a good example. After collaborating successfully, the two companies formed a joint venture that manufactures televisions with organic light-emitting diode screens.

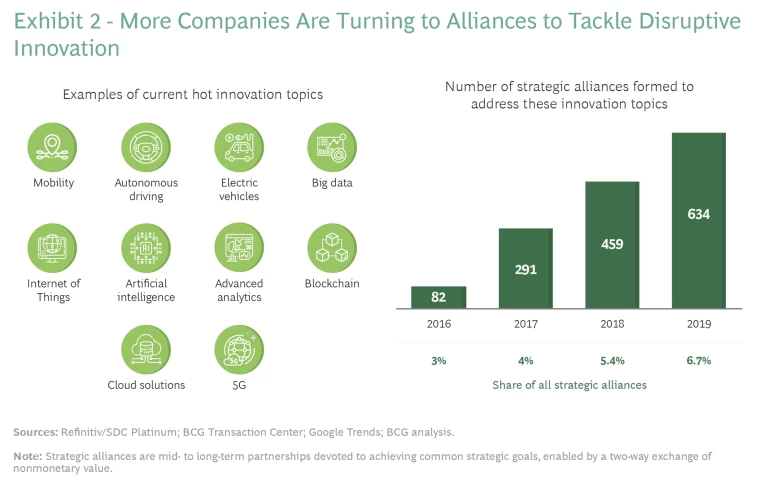

Companies often have several motivations for forming alliances. Of the 200 alliances we studied that were formed in 2019, acquiring know-how, distribution, and scale were the most frequently cited objectives. But the innovation power of alliances is increasingly becoming a key motivation. We counted 634 strategic alliances in 2019 devoted to such hot tech topics as mobility, big data, artificial intelligence, blockchain, and IOT. Three years earlier, only a few dozen a year were formed. (See Exhibit 2.)

These arrangements can be powerful tools for innovation, which often requires collaboration and the pooling of different capabilities among different partners. Because innovation also requires agility and speed, alliances tend to be preferable to joint ventures or mergers, which take longer to set up. Alliances also allow companies to share risk in investments with uncertain outcomes—and are easier to exit if a program fails.

What It Takes to Build an Alliance That Creates Value

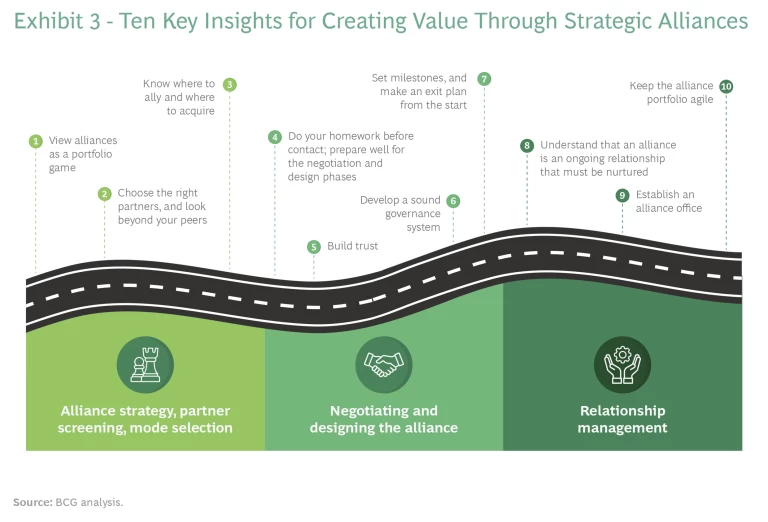

By analyzing a number of alliances and interviewing a range of executives and other experts, we were able to identify ten key insights into building a successful alliance. They cover three broad topics: alliance strategy, partner screening, and mode selection; negotiating and designing the alliance; and relationship management. (See Exhibit 3.)

Alliance Strategy and Partner Selection. It’s important that companies view strategic alliances as a portfolio game. Because alliances are more agile and require less commitment than other types of collaboration, companies can team up with the best potential partner for each topic that aligns with the company’s strategy. A portfolio also enables companies to better enjoy the benefits of larger scale.

Daimler, for example, is tapping top capabilities across the industry to address the future of mobility by using a portfolio of alliances as well as joint ventures. In electric mobility, it has alliances with Beijing-based BAIC Group, which owns several auto companies, for the China market and with US electric-bus maker Proterra. It’s also partnering with BMW, Bosch, and Torc Robotics to develop autonomous driving systems and with ChargePoint for electric infrastructure solutions.

Pfizer draws on a broad ecosystem of partners along the pharmaceutical value chain and product life cycle, spanning research, drug development, manufacturing, commercialization, and distribution. This is how Pfizer came to partner with BioNtech and other companies to create a COVID-19 vaccine in record time. (See “How Strategic Alliances Helped Pfizer Achieve Its Moonshot Challenge.”)

How Strategic Alliances Helped Pfizer Achieve Its Moonshot Challenge

Incredibly, by early November Pfizer and its strategic alliance partner BioNTech had produced a vaccine that was proved to have a 95% efficacy rate in clinical trials. By December the company had manufactured 74 million doses. A few short months later vaccines were being distributed across the globe. Pfizer recently announced that it would provide up to 3 billion vaccine doses in 2021.

The Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine program demonstrates a number of key success factors for unleashing innovation through strategic alliances. One is the importance of picking the right partner with the right capabilities. BioNTech, for example, contributed its proprietary messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) vaccine platform, a technology for synthetically creating vaccines by using a pathogen’s genetic code. This allows for dramatic increases in timelines for vaccine discovery. Pfizer leveraged its entire ecosystem—vaccine R&D, regulatory expertise, a global manufacturing footprint of 40 company-owned facilities and 200 suppliers, and its distribution network—to make this lofty goal a reality.

The vaccine initiative showcased the immense value of a portfolio approach to alliances. Like other leading biopharmaceutical companies, each of Pfizer’s core businesses draws on a broad ecosystem of partnerships that span the entire pharmaceutical value chain and product life cycle, from early discovery and drug development through commercialization and distribution. Pfizer had already established a relationship with BioNTech, for example, through an initial R&D collaboration with the company in August 2018 to develop mRNA-based vaccines for preventing influenza.

For the COVID-19 vaccine, Pfizer and BioNTech have also recently formed alliances with Brazil’s Eurofarma and South Africa’s Biovac to manufacture doses and distribute them to low- and middle-income countries. In addition, Pfizer has worked with packaging company Softbox Systems to safely distribute the vaccines in high-performance parcel shippers developed specifically for ultra-low temperatures.

Pfizer also illustrates the value of keeping its alliance portfolio flexible and looking beyond industry peers for partners. That approach helps the company pursue new opportunities in adjacent businesses. A collaboration between Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Fitbit, for example, is working on wearable devices that can make it easier to diagnose atrial fibrillation and thus reduce the risk of strokes and other life-threatening events. Another Pfizer collaboration, a multiyear strategic alliance with Ochsner Health, works to develop innovative models and tools to improve the productivity of clinical trials.

The most critical factor in the success of an alliance is to choose the right set of partners. According to a study by Swiss public research school University of St. Gallen, roughly three-quarters of failed alliances can be attributed to the wrong choice of partners and lack of commitment.

One key insight from our research is that it’s critical to figure out which kinds of collaborators can help achieve the alliance’s strategic objective. If the goal is to enter new markets or expand scale, partners within the same industry are often the best fit. A good example is the Renault, Nissan, and Mitsubishi alliance , which collaborates on purchasing, engineering, and manufacturing while maintaining each OEM’s brand identity. If the objective is to acquire new capabilities and innovate, however, companies should be willing to look for partners in different parts of their value chain—and even beyond their own industry. Among Google’s many innovation-based alliances, for example, is its relationship with upmarket eyewear manufacturer Luxottica, which it relies on for developing wearable devices. The alliances between Tesla and Panasonic to develop and produce lithium-ion batteries for electric cars and between Uber and the Spotify for mobility solutions illustrate how participants can leverage their partners’ different roles in the value chain to innovate.

It’s also important that the collaboration partner be the right fit throughout the life cycle of the alliance. Does the partner have sufficient capabilities and experience with its alliances, for example, and a reputation for providing good reciprocal give and take? Companies should also do their research to ensure the potential partner is financially sound and presents no legal or reputation risks.

In addition, companies need to know where to ally and where to acquire. In some cases, an outright acquisition is the best route.

Negotiating and Designing the Alliance. Companies must do their homework before contacting a potential partner. They need to prepare well for negotiations and design. They should also develop a game plan for each phase of the negotiation and design process.

It is critical to build trust with partners from the outset. Remember that, unlike with an acquisition, the key objective of an alliance isn’t to get the transaction done—it’s to capture the highest value from the relationship. Approach the negotiations constructively, and don’t try to conceal agendas. Both sides, even if they have well-entrenched corporate cultures, should find common ground and commit to a shared set of values for the partnership. Companies should approach the relationship with an “abundance” mindset—viewing it as a pie that can grow larger as each partner expands on the alliance’s achievements, not as a fixed entity from which maximum gain is to be extracted.

Set milestones, and plan on how to exit the alliance. Expectations for the alliance over a range of time horizons—such as quick wins, medium-term goals, and ultimate goals—and a detailed roadmap for the partnership’s life cycle should be established early in the negotiating process. It’s important to determine how the value created through the alliance will be shared among the partners and to define conditions, processes, and a time frame for exiting the arrangement. When aluminum manufacturer Alcoa and mining company Rio Tinto formed a strategic alliance to develop a low-emission aluminum production process, for example, they agreed on a one-year target for the collaboration to either evolve into a joint venture or dissolve. The alliance fulfilled its objectives, and the two companies decided to form a joint venture, Montreal-based Elysis.

Furthermore, companies should develop a sound governance system. Diligently designing and negotiating a governance structure will help ensure that the partnership is sustainable and can create value. The governance structure should carefully distribute power in the steering body and specify each partner’s role in operations. Although many archetypes exist for alliance governance structures, only a design tailored for the desired strategic objective and partners’ unique capabilities can unleash the full potential of the alliance.

Relationship Management. Understand that an alliance is an ongoing relationship that must be nurtured. Productive partnerships develop over time, and the value they create depends on how well they are executed. Managing the “soft” aspects of the relationship is particularly important because an alliance, by its nature, isn’t as binding as a joint venture or merger. Therefore, it’s vital that all partners remain aligned on scope and get along well. Both sides must invest effort to nurture a successful relationship.

Conflicts will inevitably arise. Rather than shy away from differences, partners should learn to leverage them. Hewlett-Packard and Microsoft, for example, found that their complementary strengths were valuable to their alliance but also made collaboration challenging. Executives from both companies systematically documented differences and discussed them in working sessions. They learned from each other, and the collaboration benefited.

Establish an alliance office to manage the collaboration on an ongoing basis and to ensure that it remains on track to meet targets. Regular meetings among personnel at all levels of the partners’ organizations will strengthen commitment.

In today’s environment, alliances have become critical to remaining at the vanguard and securing competitive advantage.

Finally, keep the portfolio of alliances agile. Leaders should continuously assess their mix of alliances to ensure it puts them in the best position to compete as technologies, business models, and market demands change. They should remain flexible to form new alliances to meet new needs and exit those that no longer serve their purpose.

Companies have been entering into strategic alliances—with mixed results—for decades. In today’s environment of disruptive change on multiple fronts, however, alliances have become critical to remaining at the vanguard and securing competitive advantage. And the consequences of success or failure have never been greater. A sound strategic approach, a well-conceived design, and careful attention to relationship management will help unleash a strategic alliance’s powerful innovation potential.

The authors wish to thank Oskar Wilczynski for his contributions to this article.