Another Pandemic on the Horizon

Another pandemic—one that could result in more deaths and severe illnesses than COVID-19—looms. But unlike COVID-19, which took the world by surprise, this pandemic is already in plain sight. The question is, will we take the necessary steps to avoid it and its deadly consequences while there is still time?

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR)—bacteria’s development of resistance to antibiotics, the miracle drug of the last 100 years—is a growing global threat. The culprits are many, but the result is the same: bacteria acquire strengths that overpower antibiotic treatments and render them ineffective to useless. Imagine a widespread outbreak of pneumonia or meningitis or even strep throat with no effective way to treat the illness. A 2019 study attributes 141,000 deaths in high-income countries directly to bacterial AMR. Other studies project that the cumulative global AMR death toll, which currently stands at about 1.27 million, will reach 10 million by 2050—unless we act to stop it.

This report focuses on the threat of AMR, its root causes, and the failure of the market to support sufficient innovation, which has led us to where we are today. It also offers a roadmap for taking collective global action to avoid another worldwide public health crisis. In preparing it, BCG worked closely with the World Economic Forum, Wellcome, and the Novo Nordisk Foundation. We also leveraged insights from international and country-specific experts representing the US, the UK, Canada, Japan, France, Germany, and China.

An Unsustainable Ecosystem

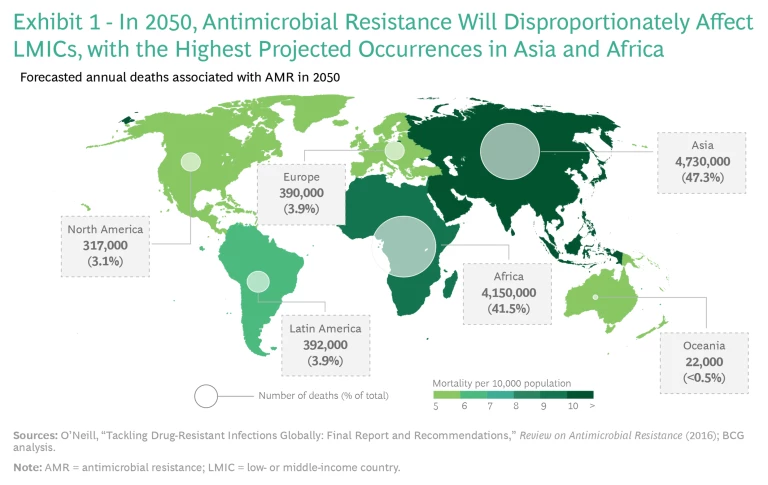

COVID-19 showed us how quickly disease can envelop the planet in the 21st century. While this pandemic hit us unprepared, AMR is a wave that has been forming for some time, and its dangers are easy to foresee. AMR is already putting an expanding societal and economic burden on both high- and low-income countries. Low-income countries are bearing the brunt of the harm, with more than 80% of global AMR deaths occurring in developing nations, and this will continue to be the case. Experts project that such deaths will exceed 4 million each in Asia and Africa by 2050. (See Exhibit 1.)

But AMR is by no means only an emerging-market issue. At least 2.8 million people develop antibiotic resistant infections each year in the US. And because of easy global travel, extensive trade, and diminishing borders, good local practices are not enough to stop the spread: both diagnosed patients and healthy individuals can transmit multi-drug-resistant bacteria to other countries. Examples of fast-spreading antibiotic-resistant diseases are already appearing. In 2003, antibiotic-resistant strains of Klebsiella, which can cause pneumonia, bloodstream infections, and meningitis, among other serious illnesses, expanded across the US. By 2005, they had spread to Israel, and by 2008, they had appeared worldwide.

AMR is a global problem that requires global leadership, coordination, and solutions. Policies need to be harmonized among countries. As with the current pandemic, until we are all safe, no one is safe. Because of their greater resources, economic powerhouses must lead the way—and it is in the best interests of their populations and their economies to do so.

Two forces are propelling the spread of AMR. One is the weakening of treatments through the evolution of the pathogens, accelerated by human behavior. The other is an absence of pharmacological innovation to respond to such novel evolution. The overall result is an innovation ecosystem that is not staying ahead of the developing danger.

Weakening Treatments

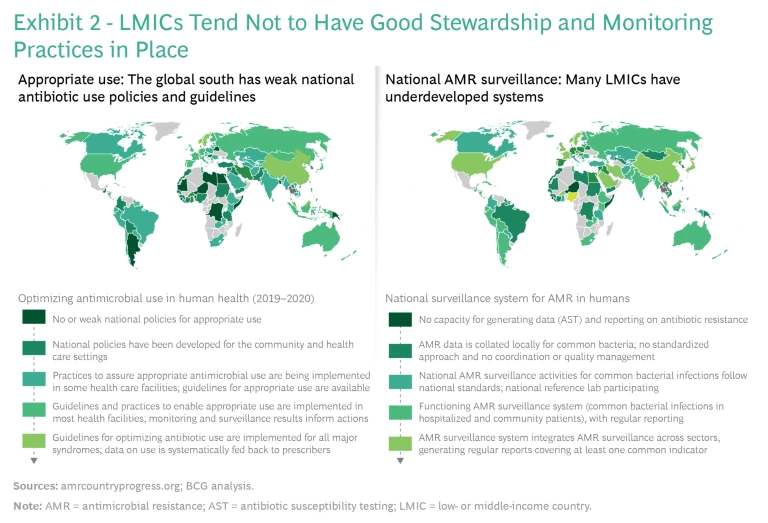

Several factors contribute to weakening antibiotic treatments. One is poor stewardship and monitoring practices, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). (See Exhibit 2.)

Almost 50% of antibiotic treatments globally are initiated with the wrong drug and without a proper diagnosis. Barriers to better practices include inadequate resources, lax regulations, and limited mechanisms for auditing the prescription, sale, and consumption of drugs. In addition, proper diagnostic tools are underdeveloped and underutilized worldwide. Even in the US, about 30% of antibiotic prescriptions are unnecessary or otherwise off target.

People introduce antibiotics into the environment in other ways as well, such as by giving antibiotics to healthy animals (to spur growth and prevent disease) or discharging antibiotics into water supplies from manufacturing sites, which further contribute to advancing AMR. The World Health Organization (WHO) and industry have been trying to address both issues for years.

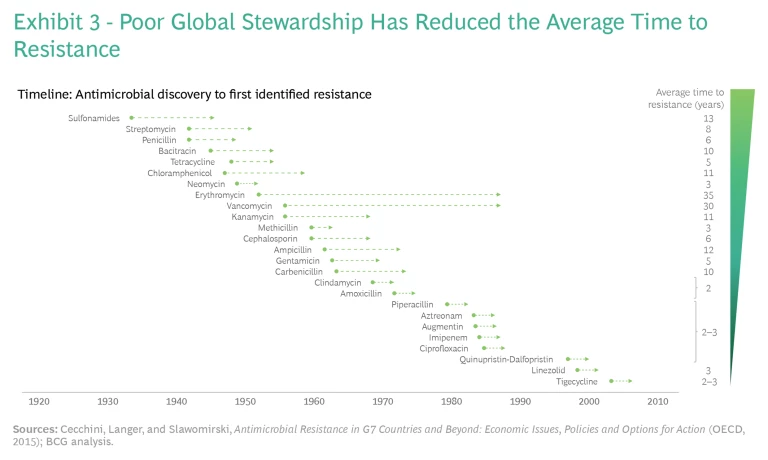

Collectively, these factors undercut the useful lifespan of drugs currently in the market. (See Exhibit 3.) For antibiotics launched from the 1930s through the 1950s, the average time to resistance was about 11 years. But for antibiotics launched from the 1970s through the 2000s, the average time to resistance fell to two to three years.

Absence of Innovation

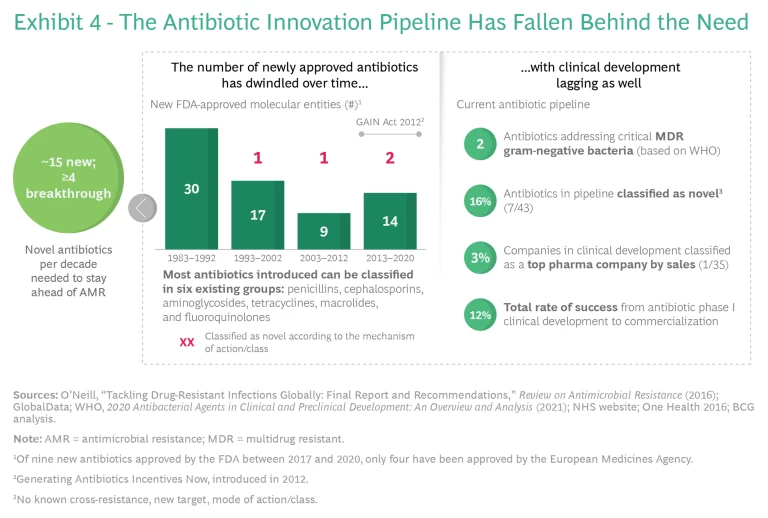

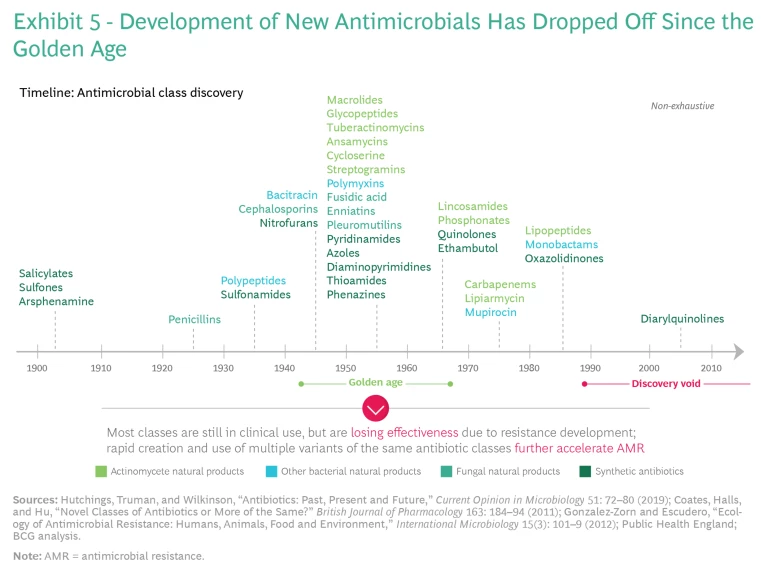

An unsustainable innovation ecosystem further enables AMR to flourish. Because of the decay of existing antibiotics, we need to replenish our pipeline of antibiotics continuously. But incremental changes in new antibiotics fail to stop the development of resistance, and the pipeline of truly novel drugs in development or coming to market has dried up. A 2016 report on how to effectively address AMR estimated that 15 new antibiotics would be needed over a decade, of which at least four would be novel breakthrough products targeting the bacterial species of greatest

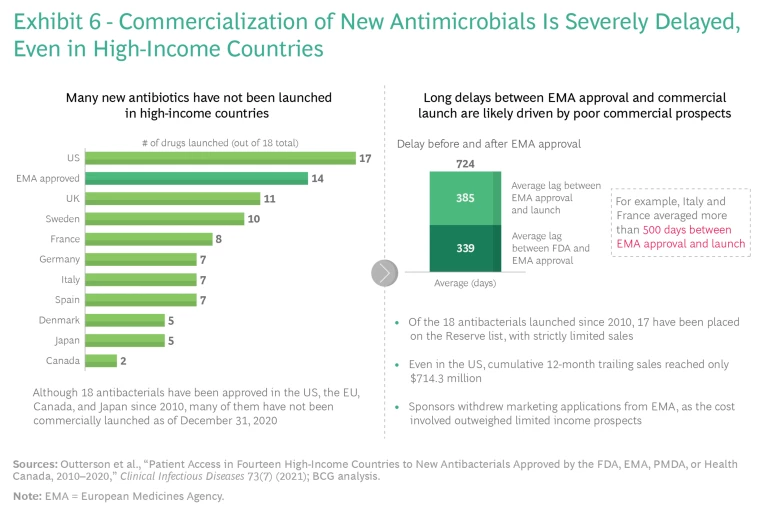

A big reason for the lack of innovation is the absence of a global market that ensures the sustainable revenues necessary to finance research, commercialization, and production at scale. This lack of access to innovation has far-reaching consequences, even in the most advanced markets. During the first eight years following market entry, 84% of all new antibiotic sales occur in the US. Outside the US, most new antibiotics do not even reach the marketplace and are unavailable to consumers. Altogether, 18 new antibiotics have been approved in the US, the EU, Canada, and Japan since 2010—but as of December 31, 2020, many of them have not been commercially launched in major markets. (See Exhibit 6.) This is almost entirely because the cost of registration and commercialization in countries outside the US exceeds expected revenues. New life-saving antibiotics are rarely, if ever, available in LMICs, which have the highest AMR burden.

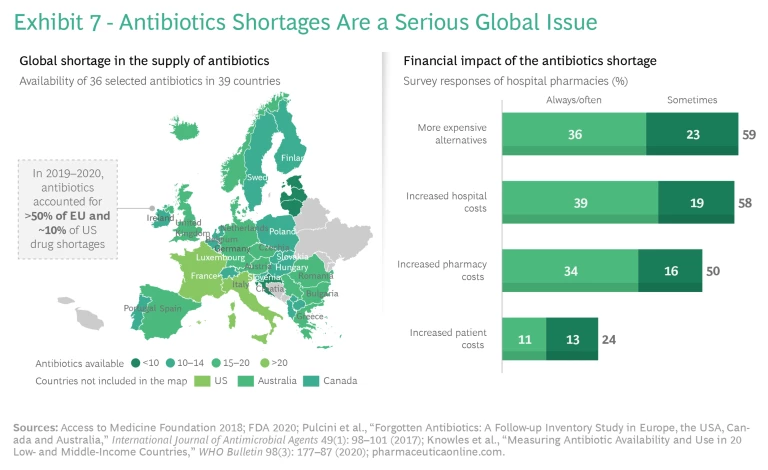

Fragmented and unreliable antibiotics supply chains—the result of too little investment in production at scale—also play a role. Shortages of important antibiotics are common in both high- and lower-income countries because many countries depend heavily on a small number of producers. Various reports cited nearly 150 antibiotic shortages in the US between 2001 and 2013. In European hospitals, more than 50% of all drug shortages in 2014 and in 2019 involved antimicrobials. The product shortages and delays carry high human and financial costs, such as the need to replace an unavailable product with a more expensive one, longer stays in hospitals, or worse outcomes. (See Exhibit 7.)

The Need for a New Model

Why is it so challenging to successfully bring novel antibiotics to the market? The core problem is insufficient revenue, which reflects a broken, volume-driven drug reimbursement model for antibiotics. Current demand for innovative resistance-breaking antibiotics in wealthy nations is limited to small numbers of very sick patients. Good stewardship by doctors and other health care practitioners, who prescribe the right antibiotic (supported by diagnostics) only when necessary and appropriate, ensures that they use novel antibiotics only as a last resort. Consequently, the most effective antibiotics get shelved to avoid development of resistance to this last line of defense. And because it emphasizes relatively short treatment courses (weeks, compared with months or years for chronic diseases), good stewardship leads to low production volume for manufacturers. This by itself might not be an issue, but when combined with low prices—caused by an underappreciation of value and comparative pricing expectations set by generics—it results in unsustainable returns. Therefore, the traditionally significant revenue contribution of wealthy nations to cover R&D costs is missing. As a result, developing markets, which have the greatest need for resistance-breaking antibiotics, do not have access to innovative treatments, as their demand alone cannot sustain the required investment.

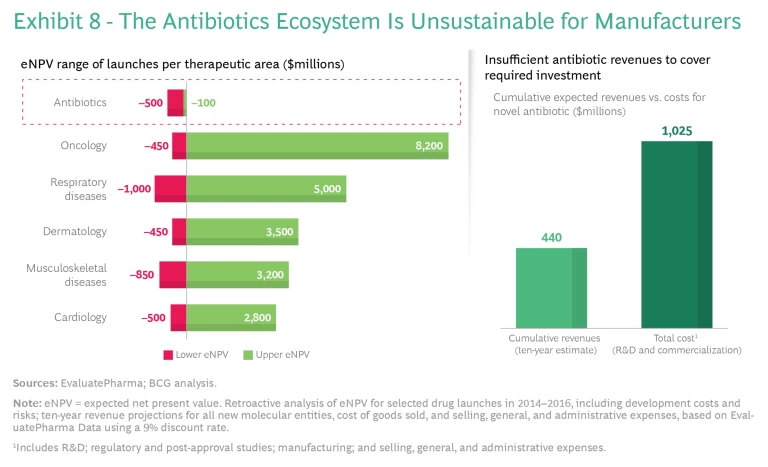

The effect globally is that pharma companies cannot justify the high costs and risks of new antibiotic development and commercialization. Compared with other therapeutic areas, antibiotics have similar R&D costs and failure rates (approximately 15 preclinical candidates per launched product), but only a fraction of the revenue prospects. (See Exhibit 8.) Major companies leave the market to pursue more profitable options in other therapeutic areas, while smaller companies cannot finance the costs of R&D and commercialization—and many end up in bankruptcy. This is a primary reason why researchers have not discovered any new major class of antibiotics since the 1980s.

Toward a New Market Model

When market forces fail to motivate adequate innovation, other incentives are necessary. Innovation can be pushed, by subsidizing at-risk investment (with government grants, for example) or pulled, by using incentives (such as guaranteed revenue) to reward success. To date, policymakers, the industry, and the philanthropic community have focused on using push incentives to drive R&D activity and AMR innovation. (See “Pushing the Market Toward Innovation.”) These and other efforts have shown limited initial success, with some new drugs coming to market and with lower barriers to entry enriching the early pipeline. But they have not changed the underlying economics and thus market attractiveness and sustainability.

Pushing the Market Toward Innovation

The AMR Action Fund is a global coalition that includes the pharmaceutical industry, philanthropic funders, multilateral development banks, and other strategic partners. It focuses on later-stage, clinical development. The fund expects to invest more than $1 billion in small biotech companies. GARDP and BARDA provide additional major push funding for clinical development.

Fundamental problems often require rethinking current structures and models. In the case of antibiotics, to develop adequate pull, policymakers may need to decouple reward from actual use by devising a market model that incentivizes development of novel drugs by purchasing significant quantities without expectation of immediate consumption. One parallel situation involves developing and stockpiling significant quantities of a vaccine against the day when a dangerous pathogen starts to spread. Another is the requirement that building owners install fire extinguishers even though everyone hopes that the devices will never be needed.

A new incentive model is essential to support continuous innovation of truly novel antibiotics. Pharma investors have repeatedly shown that they are willing to accept high development risks if the potential (although not the guarantee) for a high reward is in the offing. But aligning societal and industry interests requires establishing clear targets and reliable instruments.

New Ecosystem Priorities

AMR policy and progress should focus on truly novel treatments by creating a sustainable innovation ecosystem that leverages existing private-sector R&D and public-private collaborations. Given the required investments and probabilities of success, only the private sector can achieve the necessary volume and variety of innovation. But the private sector’s capabilities will come into play only if a sustainable ecosystem—involving both push and pull incentives—is in place to appropriately reward success. Such an ecosystem must insure society against future resistance breakouts, offer health care systems in need access to novel antibiotics, and provide sustainable returns to manufacturers and investors to incentivize continued innovation.

The starting point must be an aligned vision that addresses the underlying drivers of the AMR pandemic and the need for sustainable innovation, broad access, and appropriate stewardship.

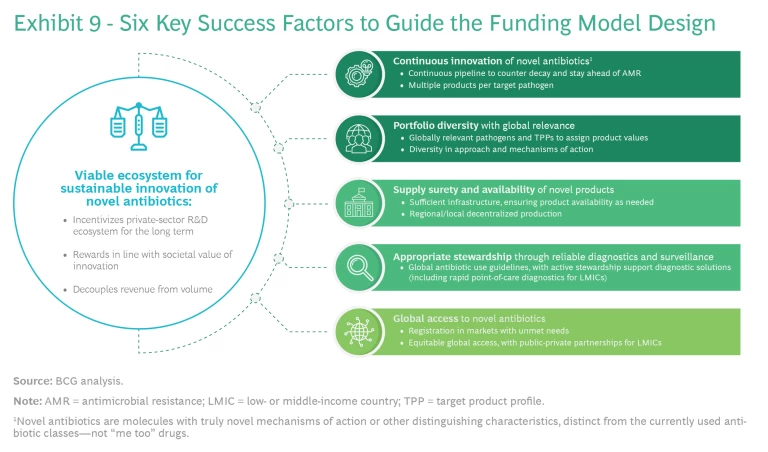

Public and private efforts should focus on a set of agreed-on high-impact target pathogens, using a series of success factors derived from the vision. (See Exhibit 9.)

Six success factors are crucial:

- A more viable ecosystem that aligns the interests of all participants, fostering investment and attracting talent to crucial R&D efforts

- Continuous innovation of novel antibiotics to counter the continuous decay of the existing antibiotic reserve and to stay ahead of AMR

- Portfolio diversity with global relevance, targeting globally relevant pathogens and product profiles with a range of approaches and mechanisms of action

- Supply surety and availability of novel products: sufficient infrastructure, ensuring product availability as needed and regional and local decentralized production

- Appropriate stewardship through reliable diagnostics and surveillance, global antibiotic use guidelines, and active support for diagnostic solutions, including rapid point-of-care diagnostics for LMICs

- Global access to novel antibiotics, including easy and inexpensive registration in markets with unmet needs, equitable global access, and public-private partnerships for LMICs

Pull as Well as Push

By themselves, push incentives are insufficient. They have achieved some success in reducing R&D costs and early-stage investment risks and thus lowering barriers to entry. But they have not spurred the necessary depth and breadth of innovation, particularly in supporting the late-stage pipeline and bringing novel drugs to market. Policies must foster a viable and attractive innovation ecosystem by rewarding successful development. The right pull incentives can go a long way toward increasing ecosystem sustainability and attractiveness, but they require an effective implementation model to ensure alignment with public health objectives.

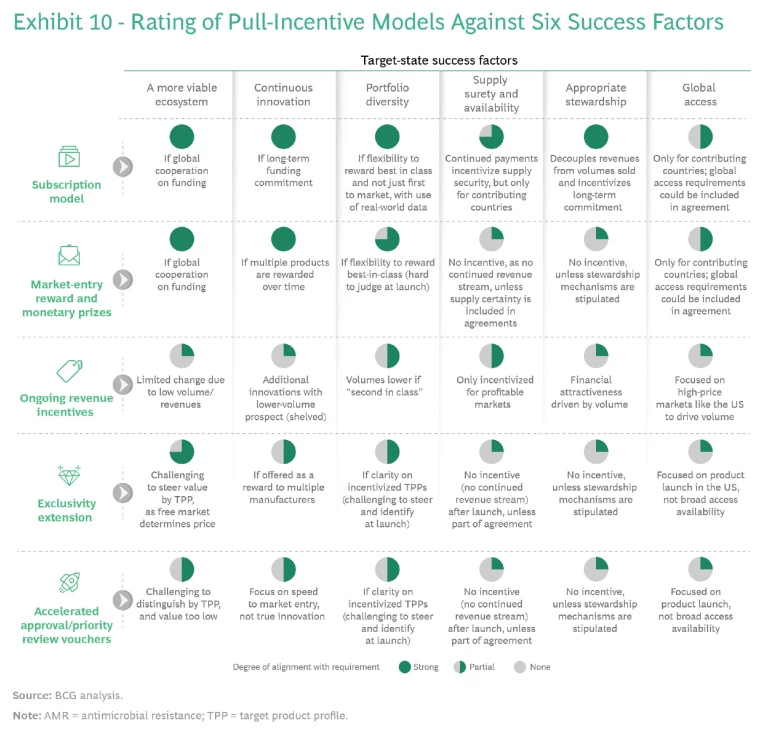

We analyzed five implementation models for pull incentives:

- Subscription Model. Fixed annual payments or minimum revenues for a set period in return for sufficient antimicrobial product supply guarantee, delinked from the volumes sold

- Market-Entry Reward and Monetary Prizes. One-off or milestone-based payments to reward completed development stages (typically late-stage R&D) or market launch of new antimicrobials

- Ongoing Revenue Incentives. Minimum price guarantees or reimbursement system carve-outs to reflect public health effects and societal value of new antimicrobials

- Exclusivity Extension. Patent extensions granted to the successful antimicrobial innovator with applicability to already approved drugs (potentially tradable between firms)

- Accelerated Approval and Priority Review Vouchers. Vouchers for accelerated assessment and approval of antibiotics or other products under development by the same company (typically tradable between firms)

Various pilot versions of these models for antibiotics and other treatment areas have been tried over time, with differing degrees of success. We assessed each model against the six success factors. (See Exhibit 10.) Each model seems workable in theory, and each comes with distinct practical advantages and disadvantages in implementation, which will affect its political support and feasibility. The following considerations underpin our recommendation for a preferred model that has the best chance for successful implementation.

Decoupling Sales Volume and Use. This objective is key if pull incentives are to serve as the basis for a viable innovation ecosystem. All models except the ongoing revenue incentive model provide for decoupling.

Global Alignment. The subscription and market-entry reward models require global alignment on priorities, the size of the prize, and fair sharing. Reaching global consensus on such provisions would be a major achievement, but exclusivity extensions and accelerated approvals could still occur on a national (such as the US) or regional (such as the EU) level. These models do not require alignment on an appropriate price level, only on the time for extension (which is much less controversial), since the free market will determine price. For example, a pharma company that owned a blockbuster drug could buy the extension at a high price from a smaller player. No mobilization of new spending or reduction in current spending is would be necessary; only existing spending would be extended, which would mean less disruption to the system.

Post-Market-Entry Support. Models that reward companies with a pooled group of incentives (market entry reward, exclusivity extension, or accelerated approval, for example) when they achieve market entry do not inherently incentivize the post-market-entry support needed to drive access, supply, and stewardship. Despite contractual obligations, companies could decide to terminate sales or abandon treatment areas (to the point of declaring bankruptcy), which would undermine ecosystem sustainability and require public institutions to step in.

Control over Budget and Public Health Impact. All models entail budgetary trade-offs for policymakers. In most models, the payer decides the amount of reimbursement for a particular novel antibiotic. However, transferrable rights, such as exclusivity extensions, would be traded on the free market out of the control of the payer. The costs to payers from patent extensions and delays to generic entry can be significantly higher than paying antibiotic manufacturers adequate incentives in the first place. Such a system decouples the price paid from the value of the antibiotic to society and could have a negative budgetary impact in other therapeutic areas (as well as potentially limiting access to treatment in these areas in regions that rely on generics to provide broad access). Therefore, although the exclusivity extension instrument is easy to implement, it might generate resistance from policymakers and payers, as it can be more expensive to health care systems from a comprehensive perspective.

Global Access. None of the models adequately addresses the issue of global access; they deal only with innovation. Although innovation is an important prerequisite for global access, policymakers and company planners should look at global access separately and apply dedicated approaches to it, making every effort to ensure that the included models do not prevent or impair any such approaches. (See “Ensuring Global Access.”)

Ensuring Global Access

- Clinical Trials. Phase-3 clinical trials should be performed, in part, in LMICs to address the future expected burden of resistance and to accelerate trials.

- Out-Licensing to Generic Companies. Partnerships with generic companies should be subjected to same considerations as apply to innovators (that is, stewardship and volumes delinked from revenues).

- Differential Pricing. The prices set should enable both appropriate stewardship and patient access, where needed, with the potential for discounts tied to adherence to good stewardship practices.

- Global Partnerships to Accelerate Registration. Innovators should partner with public-private partnerships and foundations to drive accelerated registration and market access processes in LMICs.

- Stewardship and Monitoring Requirements. Innovators should partner with global and regional organizations to develop LMIC-focused educational programs and diagnostic approaches for point-of-care testing.

An Imperfect but Viable Solution

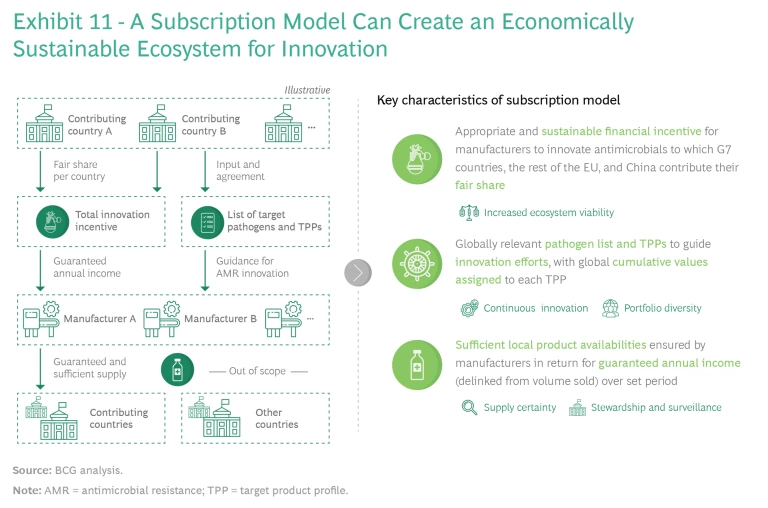

On the basis of this assessment and further reflection on implementation considerations, we believe that the subscription model is the strongest option. It can be adapted to satisfy almost all of the key success factors, whereas, absent complex adaptations, the other models fall short on multiple dimensions.

The subscription model is not perfect, and the eventual solution will likely require a mix of different instruments, including both push and pull mechanisms. But this model appears to have the best profile for reinvigorating the AMR ecosystem—and policymakers should seriously consider it. The subscription model addresses most of the requirements for rewarding innovation fairly and ensuring post-launch sustainability for new treatments. In this critical respect, it is superior to the other funding models. The subscription model is applicable in a wide range of systems, given the public and political will to implement it. Several countries are already preparing for or piloting the model, and their experiences offer valuable lessons while also highlighting the model’s broad applicability. Notwithstanding its superiority, however, effective implementation depends on overcoming multiple barriers—the subject of the next section.

Overcoming the Barriers to the Subscription Model

The subscription model can create a viable and sustainable ecosystem for developing new antibiotics, but its success depends on several factors. (See Exhibit 11.)

One is that key countries must take the lead on establishing a joint innovation funding model and not insist on global participation. Global alignment on one or more models would be ideal, but it is unlikely. Alignment among the major pharmaceutical-consuming countries would be more than sufficient, given that the G7 nations, the broader EU, and China represent about 80% of global pharma sales. These partners need to agree on the following cornerstones:

- Appropriate and sustainable financial incentives for manufacturers to innovate, to which the G7 nations, the rest of the EU, and China must each contribute their fair share

- Development of globally relevant target product profiles (TPPs), based on the WHO priority pathogen list, to guide innovation efforts, with global cumulative values assigned to each profile as a basis for setting incentives

- Firm commitments by manufacturers that they will maintain sufficient local-level product availability and appropriate stewardship in return for guaranteed annual income (delinked from volumes sold) over a set period

Multiple implementation considerations must be addressed at both the supranational and the national levels. Those at the former level include the general mechanics of the subscription model and the prerequisites for enabling local implementation. Those at the latter involve adjusting the model to deal with country-specific technicalities and enable local implementation.

Supranational Considerations

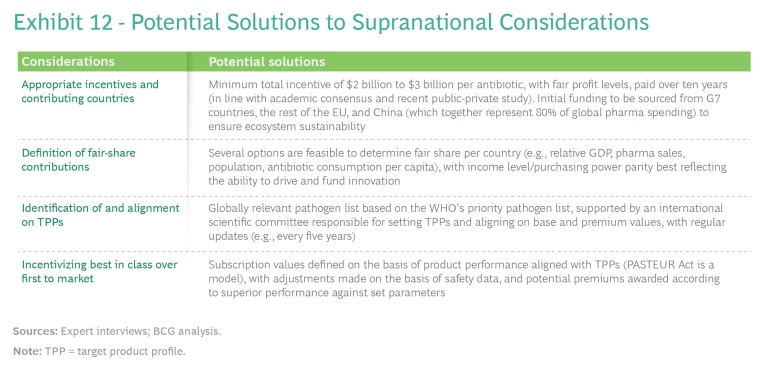

Countries need to provide practical answers to several key questions before they can move forward with a subscription model solution:

- What per-antibiotic incentive is appropriate to establish a sustainable ecosystem for manufacturers, and which countries should be key contributors to ensure success?

- What is a suitable way to define fair-share contributions per country to allow for transparency and national budget planning?

- What is the best way to define globally relevant priority pathogens and specific TPPs (including values) to facilitate alignment and transparency on innovation priorities?

- What policies will best incentivize competing manufacturers to focus on best-in-class innovations over first-to-market innovations, in order to create a self-sustaining innovation ecosystem, balance risk and reward for manufacturers, and ensure optimal value for financing countries?

We will explore potential responses to each question. (See Exhibit 12.)

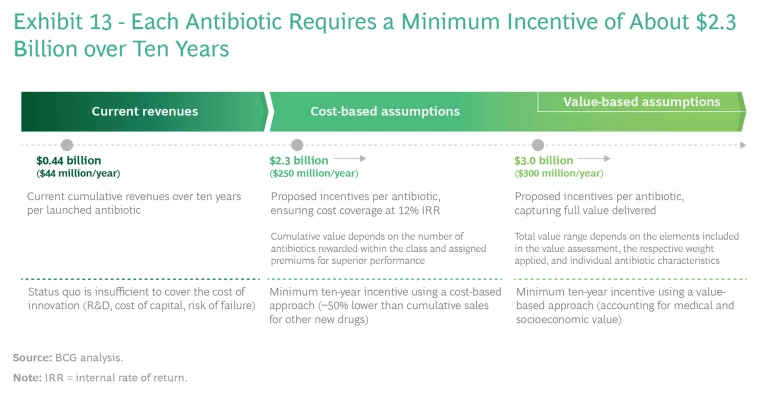

Setting Appropriate Incentives. An incentive system can be built on either of two bases: the cost of developing and marketing a new class of antibiotics, assuming reasonable returns on investment, or the actual value that the drugs deliver. (See Exhibit 13.)

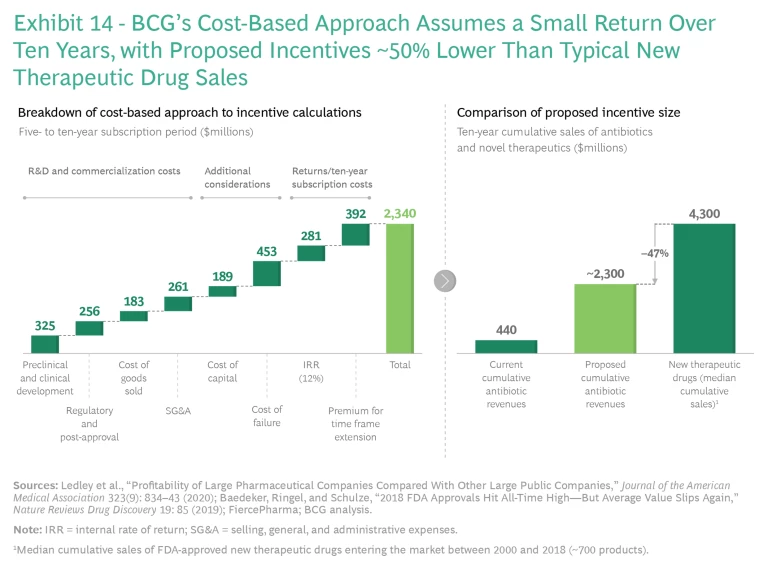

Multiple academic studies, including two released in 2021, have estimated that the required incentives using a cost-based approach fall into a range from about $1 billion to about $5 billion per novel antibiotic. These studies assume a reasonable return on investment (commonly 10% to 12%, as this is the minimum hurdle rate that a large pharma company will typically consider as a basis for investment) that also covers the cost of failed investments and profits that are significantly lower than those of top-selling drugs. The key drivers of variations are assumptions involving costs and probability of success. To reach the higher end of the range, the most recent model by Kevin Outterson of Boston University assumes higher costs and a lower probability of success, resulting in a best estimate of about $3.1

A value-based approach would likely point toward even higher incentives, as it would reflect the full societal benefit of the antibiotics. Multiple factors go into such a calculation, including transmission value (prevention of the spread of disease among a wider population), insurance value (the value of having sufficient treatments available in the event of a resistance outbreak), diversity and novel action value (the value of having a range of approaches to tackle a specific resistance and being able to exploit increased susceptibility of bacteria to other treatments), and enablement value (the value of being able to perform surgeries and other treatments and, conversely, the costs to the health care system of not being able to perform those necessary treatments). As yet, researchers have not performed exhaustive value calculations, but the actual societal value of antibiotics is probably significantly higher than current cost-based estimates suggest. One big hurdle is that implementing such an approach would require global alignment on the identity and relative weighting of key value elements, which could diverge in different economies.

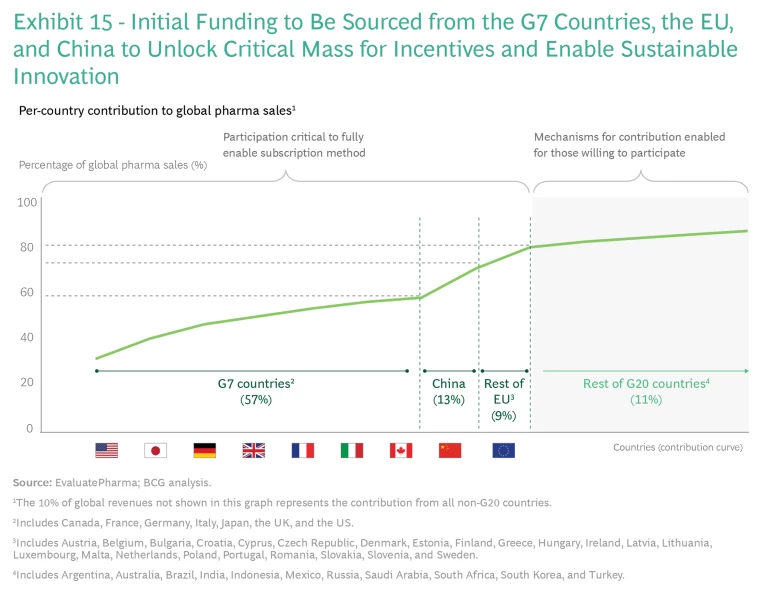

Fair-Share Contribution. Since the G7 countries, the EU, and China are responsible for 80% of global pharmaceutical sales, focusing on these markets offers the highest probability of success in implementing a globally aligned, sustainably sized subscription model. (See Exhibit 15.)

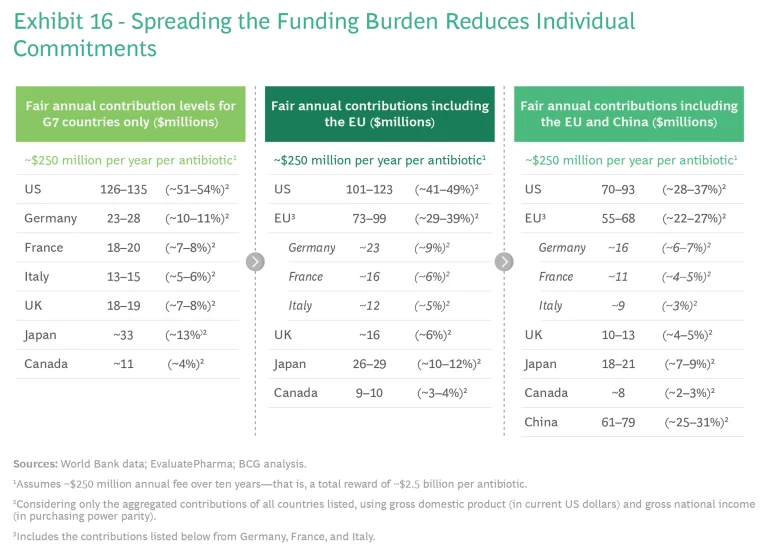

Spreading the funding burden would reduce the required level of commitment in individual countries, while collecting a total global sum that incentivized the innovation. (See Exhibit 16.)

Multiple criteria may be relevant in determining each country’s fair-share contribution, each with its own rationale and benefits. Population size, for example, is easy to implement as a criterion and reflects the protection or insurance value of novel antibiotics. Share of global pharma sales, for its part, reflects each country’s ability to drive innovation and the value it would receive, based on its historical willingness to pay for the results. And antibiotic consumption per capita links contributions to actual need, and rewards countries that exercise better stewardship.

Prudence suggests that the best criteria to use combine share of global GDP and gross national income on a purchasing power parity (PPP) basis. GDP is the most common measure of an economy's size and growth, and it is easy to implement and update with off-the-shelf data. Gross national income reflects national wealth, adjusted by local purchasing power; like GDP, it readily adapts to implementation and updating with new data available annually. The numbers in Exhibit 16—which we present to stimulate discussion—identify proposed funding levels by country based on this logic and an assumed annual global funding need of $250 million over ten years. We acknowledge that this is an entirely value-based consideration, and this discussion and alignment must realistically sit in multilateral political forums such as the G7 and G20.

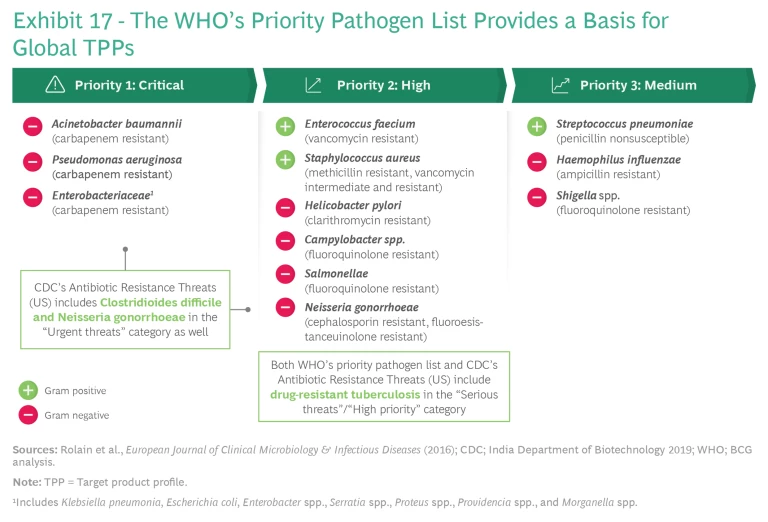

Target Pathogens and Solutions. The WHO’s priority pathogen list provides the basis for identifying target pathogens. (See Exhibit 17.) The WHO makes only small variations among countries, which permits rapid alignment. An international scientific committee composed of leading infectious disease experts, scientists from top-contributing countries, and representatives from international organizations could complement this highly valuable work by providing guidance on the value of TPPs globally to help individual countries avoid ranking and incentivizing them differently. Countries could then assign and align on the total aggregate dollar value of each product profile. The committee could update the list every three to five years (changes would not affect R&D assets already in the works from earlier lists).

Best in Class over First to Market. In the absence of proper design, a subscription model might incentivize manufacturers to be the first to bring a new treatment to market instead of focusing their efforts on developing a best-in-class drug. Incentivizing best-in-class development involves answering three main sets of questions.

- How many antibiotics per novel class must be incentivized to create a sustainable ecosystem, and what incentives are appropriate for second-in-class and later products?

- How should superior product profiles be rewarded, and what parameters are the most suitable ones to measure?

- How can incentives reward a broad spectrum of activity against multiple TPPs while ensuring that the system does not charge contributing countries twice for the same R&D and marketing costs?

With respect to the first question, offering rewards for multiple products in the same class should hinge on whether the subsequent products show superior performance or resolve safety or efficacy issues that beset the first-to-market products. Such improvements could earn lower-level rewards. In exceptional cases, products coming to market simultaneously (say within one year) might receive rewards collectively, to ensure predictability for innovators.

The answers to the second and third questions could lie in a balanced scorecard or point-based system governed by predefined parameters and agreed-on values upfront. This arrangement could be used to reward both superior product profiles and activity against multiple pathogens.

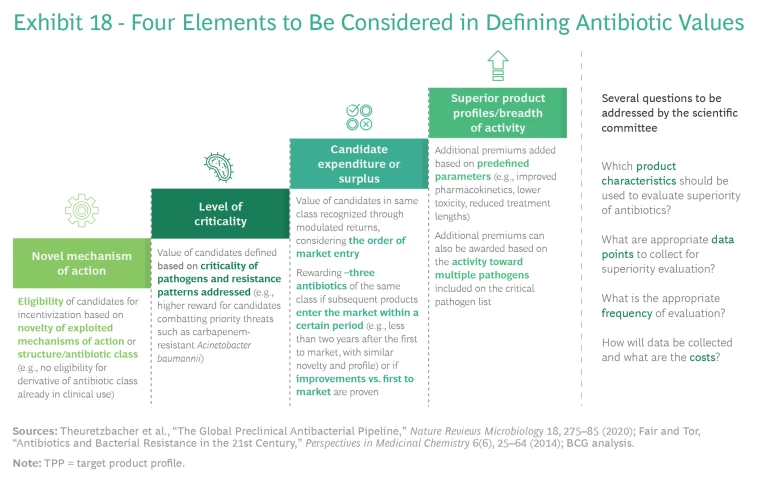

Planners should take four elements into account in defining a points-based system to reflect antibiotic values: novel mechanisms of action, level of criticality, candidate expenditure or surplus, and superior product profiles or breadth of activity. (See Exhibit 18.)

The international scientific committee described above could support this process and, consistent with WHO guidance, answer several key questions:

- Which product characteristics should evaluators use to judge the superiority of antibiotics?

- What data points should they collect for superiority evaluation?

- What is the appropriate frequency of evaluation?

- How should data be collected, and what are the associated costs?

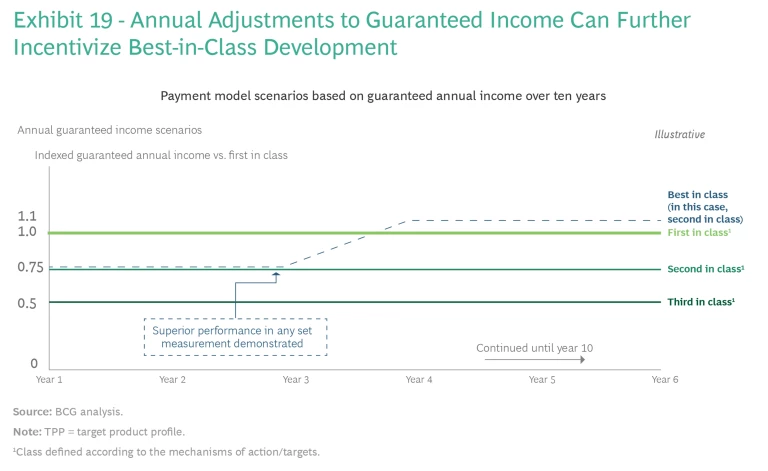

Introducing annual adjustments to guaranteed annual income could further incentivize best-in-class development. The international scientific committee would determine the amount of guaranteed income for participating manufacturers in year zero on the basis of TPP alignment and entry to market (whether a company has been first or second to market) to incentivize fast development. Annual payments over time (say, ten years) would give manufacturers more flexibility to review safety and efficacy data and to make adjustments to best-in-class antibiotics.

For example, manufacturers of the first three products per class (defined according to the mechanisms of action or targets) would receive guaranteed incomes for those products, with potential adjustments tied to two scenarios. (See Exhibit 19.) First, the minimum guaranteed income would remain unchanged in the absence of safety issues that resulted in removal of the product from the market. (For example, companies might receive 100% of the TPP value for first to market, 75% for the second, and 50% for the third, in a particular class). Second, manufacturers of products with better efficacy would receive an additional premium. The international committee can make reasonable but meaningful adjustments to income (such as an increase of 20 to 30 percentage points to close the gap between the later but more efficacious product and the first-to-market product) if clinical data or real-world evidence demonstrates a newer product’s superiority to the first-to-market treatment.

The above-mentioned scientific committee would define the recommendation for such decisions that would need to be implemented through national mechanisms.

National Considerations

Even with strong supranational alignment, any solution to AMR must reflect local health care system realities. The model will need to sustain funding that transcends governments or political parties in power. It should also be tailored to local health care systems and processes to ensure access and incentives for the local supply chain. We interviewed market experts in the US, Canada, Europe, and China to identify specific national barriers to implementation—as well as potential solutions to these hurdles—and to assess the general viability of a subscription model in each major market.

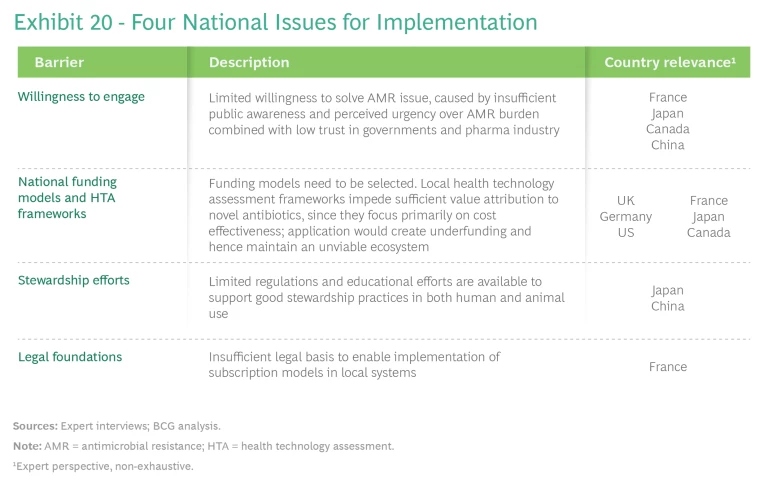

The issues we encountered fall into four areas: willingness to engage, national funding models and health technology assessment (HTA) frameworks, stewardship efforts, and legal foundations. (See Exhibit 20.) Each requires local adjustments to the model to enable local implementation. Although some barriers, such as those related to stewardship efforts, affect all pull-incentive models, the need to embed a subscription model in local policies amplifies other barriers.

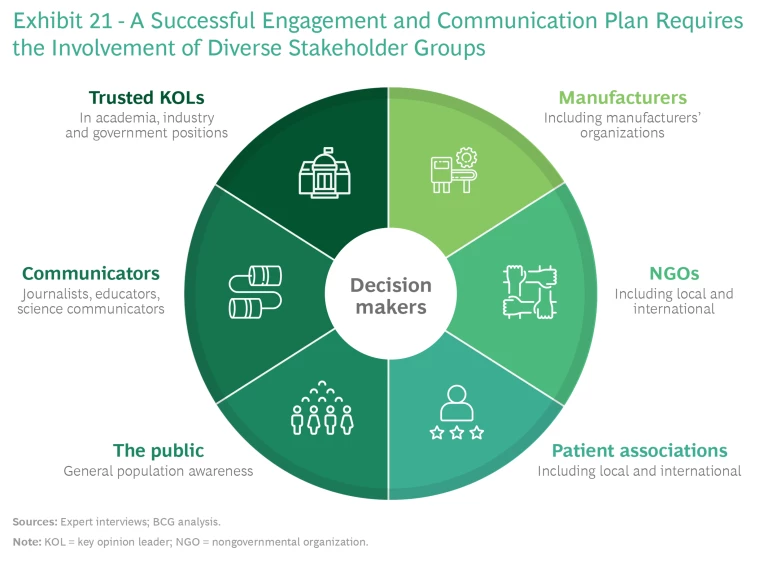

Willingness to Engage. Spurring decision makers to take action requires elevating their awareness of the coming AMR pandemic and conveying the urgency of the threat. This in turn requires engaging a range of stakeholders at the local and international levels through a campaign that uses globally aligned messaging to lay out the risks of inaction and the benefits of participation to contributing countries. (See Exhibit 21.) These benefits include accelerated and early access to innovation, guaranteed supply, the opportunity to serve as global and regional role models, and global support to local economies through investments in local companies. Messaging should take into account local and regional contexts and be directed to the most appropriate forums for delivery. The G7 nations are a good place to start.

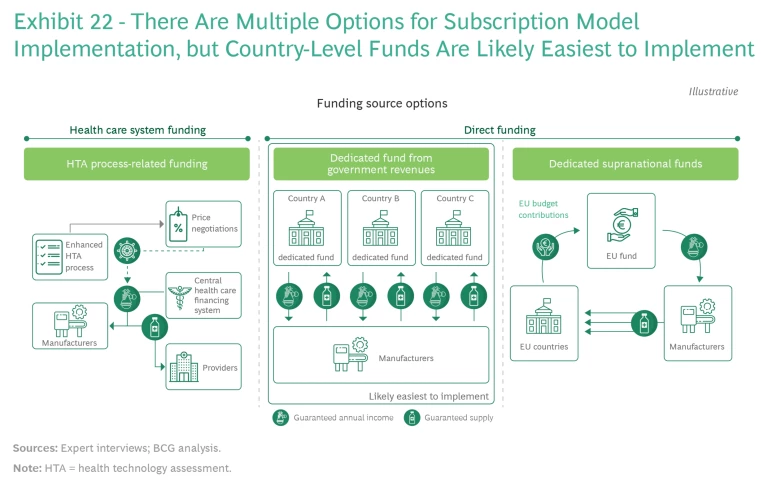

National Funding Models and HTA Frameworks. A key issue at the national level is the choice of a funding model, which must avoid disrupting existing health financing systems, transcend political or governmental shifts, and allow for the required size of funding. (See Exhibit 22.)

There are three potential models:

- Financing through established valuation and reimbursement mechanisms, such as HTAs

- Dedicated funds, such as for innovation or for pandemic preparedness, outside already-earmarked health care budgets

- A supranational pooling of resources (in the EU, for example)

The first funding model option involves funding AMR innovation through existing systems for financing health care, using enhanced HTA processes to capture the full value of novel antibiotics individually. However, current HTA systems do not fully capture either the wider health care system benefits or the societal and macroeconomic benefits of innovative treatments. Since relatively few patients are treated with novel antibiotics, there is little data on the benefits that these treatments provide for individual health and the broader health care system (the economic value of disease prevention, for example). Many HTA systems evaluate only current expected unmet needs, since evaluating longer-term needs can be difficult. The productivity benefits of new drugs are evaluated in some countries but not in others.

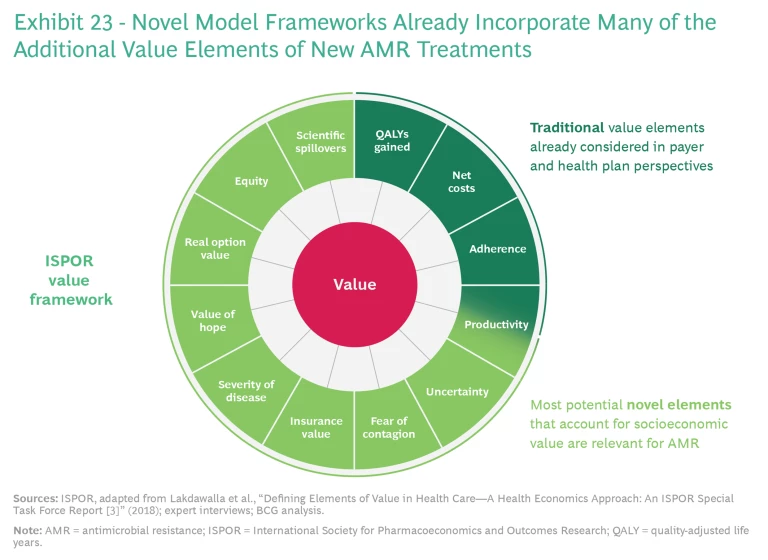

Current HTA systems would have to be adjusted to capture all of the health benefits of novel antibiotics, including their transmission, insurance, novel action, and enablement values. Novel model frameworks—such as the value framework put forth by the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research—are available that incorporate many of the additional value elements. (See Exhibit 23.) In view of recent efforts undertaken (albeit on a limited basis) by organizations such as the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, we believe that this approach is methodologically feasible.

Under the second funding model option, dedicated funds from national government revenues would be established from budgets for innovation or emergency preparedness, resulting in sufficient authority at the local level and requiring limited system stakeholder engagement. Many countries already have experience with both innovation and special-purpose (such as emergency preparedness) funds. Since the legal basis and precedents for such funding are established in most countries, rapid implementation is possible. One downside risk is that these types of funds may be exposed to changing political circumstances.

The third funding model option—funding pooled at aggregate levels, such as the European Union—ensures sufficient and fair incentives while reducing complexity. Health care in Europe is not within the direct purview of the EU, but exemptions followed during COVID-19 could serve as blueprint for a regional funding model. Novel antibiotics could be procured at the EU level, as were the COVID-19 vaccines, with country contributions calculated on the basis of existing EU allocation formulas. In Europe, the yet-to-be-established European Health Emergency Preparedness and Response Authority could be made responsible for defining the value of TPPs, coordinating distribution, and taking a complementary role in stewardship.

Of the three options, dedicated country-level funds are likely easiest to implement. A regional-level fund is relatively streamlined, demonstrates long-term commitment, provides a simple and transparent process for innovators, and involves little disruption to existing systems; but implementation requires a high level of stakeholder engagement and significant changes to locally governed health care systems. HTA-process-related funding produces lasting changes at the individual country level with long-term commitment and requires limited public engagement; but it necessitates a significant overhaul of the HTA process in all countries that use this process, which may involve disruption to local health care and financial systems. (Despite these hurdles and challenges, we have seen efforts to overhaul the HTA process in other special situations, such as in connection with vaccines.) In addition, the probability of low coordination among countries means that the overall system might not achieve a sufficient level of incentives.

Regardless of the option chosen, local-level pricing mechanisms would have to be applied to ensure integration into the local prescription and supply chain systems—to pay pharmacies and distributors for their services, for example—as well as to avoid perverse incentives to undermine stewardship at the provider and prescriber level.

Stewardship Efforts. Current policies focus on health care providers—for example, through the requirements of stewardship plans at vulnerable facilities with high antibiotic use (such as homes for the elderly) or linking hospital reimbursement of novel antibiotics to the use of diagnostic tests—but manufacturers could be asked to contribute more. Industry activities today focus on data sharing and awareness campaigns that target professionals. To address the limited regulations and educational efforts that are available to support good stewardship practices in many countries, manufacturers should create a stewardship plan—one that also includes recommendations on animal use—to serve as the basis for guaranteed annual income reviews. Most large biopharma companies do this already on a voluntary basis, according to the 2021 AMR industry alliance report, though these efforts are mainly focused on human antibiotic

Manufacturers can play a deeper role in enabling and ensuring appropriate stewardship in two other areas as well. First, in the area of diagnostic tools and approaches, manufacturers should support development of an applicable and affordable diagnostic approach—or recommend one—to ensure that novel antibiotics are prescribed only when needed (thus establishing and ensuring an appropriate rule of last resort). Countries should provide adequate funding support and reimbursement practices to enable providers to use recommended diagnostic approaches. Coordination between manufacturers, practitioners, policymakers, and payers will be essential to address mismatches between the individual value, commercial value, and social value of using diagnostic tools.

Second, additional funding should be dedicated to medical education and monitoring efforts. Manufacturers, contributing countries, and international organizations must commit to developing and implementing robust national stewardship programs that evidence clear political will and commitment, funding support, community awareness raising, diagnostic infrastructure development, and establishment of suitable medical education programs for health care practitioners and pharmacists.

Legal Foundations. In some countries, the existing legal framework for procuring drugs does not permit introduction of a subscription model. Changing procurement frameworks is a politically sensitive, but necessary, prerequisite for introducing a subscription model or an alternative that similarly requires the delinking of payments from the traditional procurement process.

The Way Forward

The past 24 months have shown what the world’s leading economies can achieve when they face an acute global public health crisis. Combating AMR demands no less of an effort. To get started, the leaders of the G7 nations, the EU, and China, along with the pharmaceutical industry, need to move on the following initiatives:

- Formulate a collective understanding that the parties agree with the principle of paying for access as opposed to volume (acknowledging differences with mechanisms that are in place today).

- Consider the advantages of a subscription model as the preferred method for this purpose, as it serves to increase product availability while being palatable to all stakeholders compared with other solutions.

- Define and align on a position regarding the size of the overall pull incentives required per TPP to create a sustainable innovation ecosystem. We propose that the international community commit to raising, on average, $250 million a year for each TPP for ten years.

- In collaboration with the WHO, establish a mechanism to prioritize and create a distinct valuation of TPPs. We propose the formation of a joint international scientific committee that will use the existing list of 12 priority pathogens plus tuberculosis outlined by the WHO for its work.

- Assign this committee the task of creating a framework for an enhanced HTA to clarify how to determine the value of a novel antibiotic. This framework should be in place by the end of 2022. We do not believe that the national HTAs need to be uniform across all jurisdictions, but they should share common themes to align on the common objective.

- Achieve multilateral agreement on creating a fair-share methodology to identify the amount of resources that each country must contribute. We propose a fair-share model that integrates GDP and gross national income to split the costs among the G7, other EU nations, and China.

- Acknowledge that the precise mechanisms will differ by country, since implementation and context will also be different. Countries should begin to work in parallel in multilateral efforts to identify feasible mechanisms in their country or region that follow the same principles to collectively achieve the desired size and mechanisms. This means pursuing no-regret moves to create the necessary legal foundations and, for example, adapting national HTA frameworks with the shared goals in mind.

- Urge the G20 nations, in collaboration with other global health stakeholders , to determine how to handle access and stewardship of novel antibiotics to ensure that the the efficacy of new drugs is protected while also guaranteeing that those who are most in need of them have access to them.

- Set a clear time frame for implementation, and align on the process with contributing countries. This includes a commitment to national action in parallel with multilateral negotiations to ensure accelerated implementation once the participants achieve a multilateral agreement.

AMR is on the march now. There is no time to waste. Global policymakers and the health care community need to move forward—and move forward fast—as one.