ESG regulations are growing more intricate, and businesses’ fragmented compliance efforts are proving inadequate. Companies should adopt a comprehensive approach to enable efficient risk management and reporting.

For businesses that have been trying to meet their goals and be good corporate citizens, one thing is clear: it’s imperative to comply with environmental, social, and governance (ESG) regulations in order to successfully create value. However, the ever-evolving regulatory demands around ESG issues have made compliance a challenge for many companies.

Government authorities worldwide have published a broad variety of ESG-related regulations that pertain to factors such as climate change , human rights, and diversity. For example, according to PRI Association, close to one thousand ESG-related regulations have been issued for the investment industry alone. In addition, in 2021, the US Securities and Exchange Commission called for companies to disclose information relating to climate risk, human capital (including workforce diversity and corporate board diversity), and cybersecurity risk. These and other regulatory shifts and changes have made it difficult for organizations to comply efficiently and effectively.

Companies are also facing a higher level of regulatory scrutiny and enforcement action regarding their promotional practices. The Financial Conduct Authority in the UK, for example, is moving to address greenwashing—marketing efforts that mislead the public by promoting goods as green products when they are not environmentally friendly. The scrutiny is making organizations keenly aware of the risks of greenwashing and, in some cases, forcing even CEO resignations when a sustainability claim has misled customers.

Senior leaders have typically assigned ESG issues to various departments, such as sustainability, procurement , and human resources. But this piecemeal approach has been ineffective and inefficient. It also hasn’t protected companies from penalties and negative public opinion, shielded the planet and workers from harm, or addressed regulatory concerns over greenwashing.

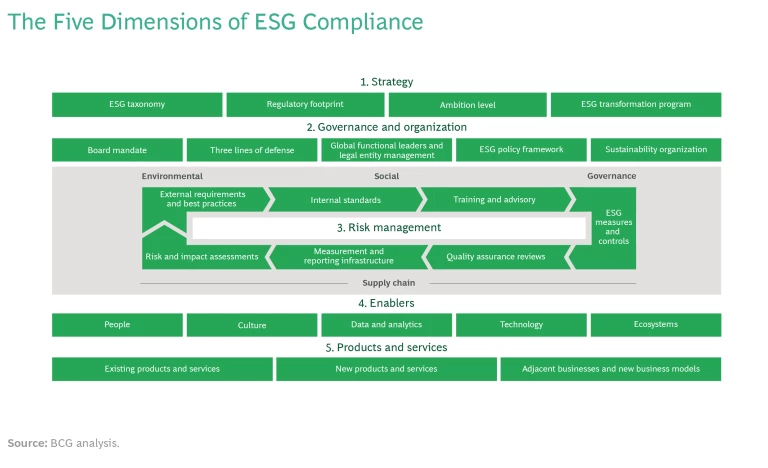

Companies, instead, need to take a comprehensive approach to ESG compliance. This article explores the key dimensions of a holistic ESG approach that enables staff, teams, and leaders to use comparable risk management practices across the organization. These dimensions are strategy, governance and organization, risk management, enablers, and products and services. By following a holistic approach, companies can manage and report on a full menu of ESG metrics and meet their regulatory obligations with confidence.

Five Obstacles to ESG Compliance

Over the past few years, various ESG issues have been rising to the top of companies’ agendas. A combination of factors—such as a company’s industry, its locations, regulatory changes, and cultural pressures—has often determined the issue of the moment.

Enlisting departmental expertise to address a pressing ESG issue has resulted in obstacles that hinder compliance efforts.

Companies have typically enlisted departmental expertise to address the most pressing issue. This has resulted in obstacles that along with other challenges hinder companies’ efforts to comply with ESG regulations and make consistent public statements.

Fragmented Approach, Limited Perspective. Leaders have managed ESG issues across departments using different protocols and controls. As a result, little coherence has formed around the ways to direct initiatives and create comprehensive standards and guidelines. As a consequence, for example, departments deploy their own risk-assessment approaches, which makes it difficult for the organization as a whole to determine its most relevant ESG issues. Departments also set up their own taxonomy and standards for data collection, analysis, and reporting.

Weak Corporate Governance. Companies’ siloed ESG efforts that have been limited in scope have not developed the governance structures needed to support risk management across ESG areas and business units. The result is weak corporate ESG governance.

Strong, comprehensive governance will become more important as regulations begin to emphasize cross-functional compliance. For example, Germany’s Act on Corporate Due Diligence in Supply Chains, due to take effect January 1, 2023, is meant to protect human rights and the environment in supply chain operations. The act addresses how these rights should be treated by companies and their external partners—supply chain providers. To comply with the act, a company should form a multidisciplinary governance triangle: procurement should look at how vendors are managed; the human resources department should assess how employees are treated; and a human rights department should consolidate the company’s approach to human rights and manage reporting.

Regulatory Inexperience. Many companies are not used to the high degree of regulatory scrutiny that the proliferation of ESG regulation brings. Unlike those in heavily regulated industries, such as financial services and health care, companies in less regulated industries have not learned what to expect when facing sophisticated regulations or how to implement changes. They are inexperienced and poorly equipped to deal with the mass of ESG regulations that is emerging—and that grows more intricate every year.

Data Shortfalls. To improve transparency, regulators are pushing companies to provide more granular ESG-related data. Companies then meet two problems: data availability and data quality.

For example, scope 3 emissions data from ecosystem partners is difficult for companies to access. In terms of quality, companies’ data collection systems are built on methodological foundations that are always evolving in reaction to—rather than in anticipation of—changing regulatory standards. As a result, the quality of the data will only improve over time.

Regulators are aware of these shortfalls. Their intention behind the continuous elevation of standards is to push companies to keep striving for more sophisticated data collection. Such frequent adjustments to regulation serve a larger purpose: to move societies forward toward progressively greater commitments to sustainability, even if companies must use interim data-collection practices in response.

Eventually, solutions designed to manage data with the detail that ESG compliance requires will become commercially available. However, until those solutions arrive, leaders should anticipate an interim period of five to ten years in which their organization will have to use intelligent workarounds and estimates to manage data for compliance.

Technology Limitations. In the past, sustainability officers could choose how to measure ESG outcomes and provide reports, and they often settled on spreadsheets. However, regulators are increasingly demanding reports that are similar to traditional financial reports. Such reporting mandates may very well be so exact and extensive that regulators are unlikely to accept spreadsheets for reasonable assurance, setting up the need for more sophisticated reporting capabilities.

A Holistic Approach to ESG Compliance

To ensure ongoing compliance with a growing number of ESG-related regulations that cut across a variety of dimensions, a company needs a holistic approach. Leaders should strive for a minimum level of company-wide synchronization of the methodologies used to manage risk and measure and report ESG progress. The resulting umbrella for ESG compliance makes effective workflows and resources available across the company while relying on the specific business expertise within each department. (See the exhibit.)

The holistic approach elevates a company’s commitment to ESG practices on five dimensions.

Leaders should strive for a minimum level of synchronization to manage risk and measure and report ESG progress.

Strategy

An ESG strategy describes a company’s ambitions (such as lowering carbon emissions) and the targets that make its ambitions real (such as reducing emissions by 10% over 18 months). To begin forming a strategy, leaders must understand the organization’s regulatory footprint and the specific ESG factors associated with its industry and the regions it operates in.

The company should then conduct a materiality assessment to identify the ESG factors that are relevant to its business and operating model. For example, the materiality assessment of a clothing manufacturer with operations in Southeast Asia is likely to pinpoint child labor standards as a potential point of concern; a coal-based energy producer’s assessment should spotlight emission levels. The sum of the issues that are most material to a business will help to inform its ESG taxonomy, which provides a common language and references to support broad programs that are designed to accomplish the company’s goals.

With these prerequisites in place, decision makers should then determine their ambition levels and targets. Any target for an ESG initiative must reflect the risk appetite of the leaders affected by the program.

Governance and Organization

Companies should establish a governance structure that covers each facet of ESG compliance, including decision making, escalation processes, committee operations, legal entity management, and roles and responsibilities. Accountability and leadership are instrumental to ESG governance, and people at all levels (including members of the board of directors) should serve in key roles during the formation of the governance structure. Boards should assign the roles, and functional leaders should assume specific responsibilities throughout the process.

ESG compliance is a discipline that usually requires a combination of detailed regulatory knowledge and traditional risk management skills. To access these skills, ESG personnel may choose to join forces or cooperate with their respective counterparts in the compliance, legal, and risk departments.

An effective approach to ESG governance is to implement the three lines of defense.

An effective approach to ESG governance is to implement the three lines of defense model, which is now a common approach to managing risk. The first line of defense comprises business owners and functions that own and manage risks. The second line is made up of personnel, such as ESG executives, who oversee or specialize in compliance or risk management. The third line comprises functions that provide independent assurance to regulators.

Risk Management

To manage ESG-related topics and ensure regulatory compliance, companies should adopt a continuous, systematic approach to risk management. This approach usually involves seven phases, beginning with an assessment of external requirements, which are dictated by the regulatory footprint of the organization; the defining of internal standards and procedures, which are designed to meet regulatory requirements; and the implementation of training modules. As part of this focus, companies can include the development of additional measures and controls to ensure compliance. Leaders should also prepare for quality assurance, put in place measurement and reporting infrastructures, and conduct regular risk and impact assessments.

Two areas of risk management—assessing external requirements and developing measures and controls—are particularly relevant to ESG compliance.

Assessing External Requirements. Once leaders have identified the ESG factors that are of the highest importance for them, they must proceed with recognizing, understanding, and responding to the regulations that are most relevant to these ESG factors. Organizations can look to the example of financial institutions, which have met this challenge by establishing a central team that is responsible for three key actions:

- Identification. The team monitors regulatory updates and identifies changes.

- Understanding. The team understands the core of the regulation and its impacts on the business.

- Ownership and Implementation. The team assigns responsibility for implementing the company’s response to a new or changed regulation.

A comprehensive regulatory database, also managed by the central team, provides an overview of current and upcoming obligations on global, regional, and national levels, as well as best-practice responses. The database can generate a regulatory calendar to help the company prepare for scheduled revisions to the rules.

Developing Measures and Controls. External regulatory requirements and internal ambitions come together as the company’s targets for various individual ESG factors. Measures and controls are the critical mechanisms to achieve these targets, and leaders can use these elements to further hone the company’s management of ESG factors.

Measures are activities designed to fulfill regulatory requirements and help the organization realize its ambitions. For example, regulations may require a company to conduct vendor due diligence to be sure that vendors respect human rights and practice sustainability along their supply chain . A vendor’s HR department could adjust hiring and promotion policies to improve diversity and inclusion, or a vendor could revise its travel policies to reduce its carbon footprint. Individual departments are responsible for implementing and maintaining the measures.

Controls are activities to ensure the efficiency and effectiveness of the measures, such as evaluations to determine if vendors’ due diligence process is thorough. Controls can include:

- Automated, system-integrated input and output devices, which can review, for example, the energy consumption of a certain distribution center

- Devices to check the effectiveness of measures, such as the introduction of a new travel policy to convert a vehicle fleet to electric energy

- Random spot testing of a supplier’s assessment process, which was implemented to avoid relationships with suppliers that are unlikely to meet sustainability requirements

- In-person assessments of implementation and adherence to new factory-safety measures, which were implemented to reduce the number of workplace injuries

Enablers

ESG enablers are the people, culture, data and analytics , technology , and ecosystems that can foster ESG compliance. The era of ESG compliance will require people who are not only familiar with the latest ESG developments but also trained in common risk management practices in their area of expertise.

Given the heavy regulatory focus on regular assurance and the variety of regulatory requirements across regions and corporate activities, many companies would benefit from implementing compliance technology solutions.

These solutions help organizations automate key aspects of the compliance process, including data management and disclosures. The financial industry’s level of compliance is again a useful example. As regulators push for mandatory ESG reporting and limited reasonable assurance, their requirements will come to match the rigor of financial reporting.

Various solutions deliver that rigor by tracking relevant KPIs and data. SAP Sustainability Control Tower, for example, brings together artificial intelligence, application development, and automation to collect and analyze real-time data and enable reporting on numerous ESG KPIs.

Products and Services

Potential customers and partners see ESG-compliant acts as signs of a company’s credibility and commitment to values such as sustainability and diversity. ESG compliance also serves as a catalyst for new ways to do business and an inspiration for new offerings and services, such as green versions of established products. In some cases, entirely

new business models

may emerge that are closely aligned with the needs of customers and the wider stakeholder community.

Putting a Comprehensive ESG Approach into Action

Companies that implement a holistic ESG approach can realize several advantages. Teams will be better positioned to manage business processes, create transparency through data, meet reporting requirements for multiple regulations, and create positive feedback loops tied to both ESG and business performance throughout the value chain.

We recommend three steps to get started:

- Conduct a health check. Conduct an ESG assessment by interviewing relevant stakeholders and reviewing the organization’s key ESG documents. It is important to take this assessment as a first step toward understanding the company’s ESG status quo, because decision makers will need to put in place an action plan to drive the necessary changes that bridge the gap between the current state of ESG factors and the targets.

- Create targets. Define targets that account for the underlying regulatory requirements as well as the company’s ESG ambitions. For example, a target may be to reduce the level of scope 2 emissions by a certain percentage by a particular date. Leaders should subsequently draft a roadmap for implementation. The roadmap should include a timeline and assign responsibilities for the various measures that the company uses to hit the targets.

- Implement the changes. Put in place the changes that will help embed the new ESG compliance approach into the organization’s operating model. Technology solutions will play a vital role in both data management and disclosures. Ideally, the solutions should also include benchmarking functionality and visualization for internal and external reporting.

Companies should move from a fragmented approach to ESG issues to a holistic one. In addition to confidently meeting their regulatory obligations, companies will reap other benefits, including boosting ESG performance, realizing group synergies, and catalyzing strategic decision making. Heightened regulatory scrutiny means that the risk of delaying is likely to be much higher than the cost of moving forward. Leaders can act knowing that more effective compliance will open the door to value creation and competitive advantage.