Catalytic specialization areas (CSAs) can jump-start and diversify an economy by tapping into current trends—enabling rapid commercial growth with relatively low investment.

Economic growth in a time of uncertainty has been a major issue for governments for several years. We are learning that if you want to emerge stronger from a crisis, it’s not enough to think big. You also have to think focused.

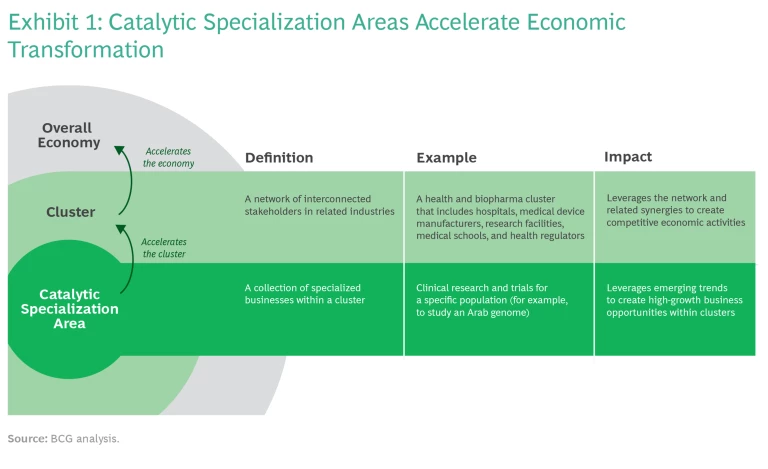

Governments can foster prosperity with an economic strategy that is targeted and agile at the same time: supporting specific industries with high-growth potential while adapting rapidly to disruptive forces. One powerful vehicle for accomplishing this is the catalytic specialization area (CSA). The CSA is a pocket of economic growth—often led collectively by government, businesses, and other institutions—in which interconnected stakeholders in related industries, usually located near each other, act together. It generates a rapidly expanding body of business activity, often oriented to exports. (See Exhibit 1.) The CSA’s innovative focus allows it to act as an economic accelerator—in which relatively small investments, and a mutually reinforcing business community, can foster rapid growth.

A typical CSA sponsor is a national government, but it can be put in place by a state, province, city, or metropolitan district. A CSA can also emerge naturally, without government interventions. There is always a specific geographic focus: a city, metropolitan area, or rural development area with a common coastline or other natural resource. The CSA is focused on a specific business domain, a subset of a larger economic cluster. For example, there are successful CSAs in fields such as aquaculture (a subset of the agriculture cluster), wellness and “silver” tourism (subsets of tourism), fintech (financial services and digital), and vaccine manufacturing (pharma manufacturing). Finally, the CSA typically emerges at the intersection of several emerging trends (including technological advances, geopolitical shifts, and social change).

Some CSAs are formed without much government direction. In other cases, the government acts deliberately to foster and advance them. Its leaders are keenly focused on promoting growth, deliberately channeling resources and support in that direction. In the most innovative domains, circumstances can shift rapidly, and governmental organizations must be flexible, adapting to new opportunities or sudden challenges—such as inflation, technological disruption, or pandemic-style crises. Focusing on specialization areas enables policymakers to be more agile in their responses, because the investment “bets” are smaller.

The Benefits of a CSA Strategy

Why focus on catalytic specialization areas rather than broader clusters? CSAs have several advantages. They allow policymakers and other stakeholders to use their resources more effectively. They enable strategic “bets” on economic growth. They tend to follow the trend of agility in government , oriented toward multidisciplinary teams making fast-paced decisions and adjusting “on the go.” The CSA model is particularly important at times like the present, when many governments must tighten and ruthlessly prioritize their budgets and respond to rapidly changing technological, geopolitical, and social trends. In times of uncertainty, the most robust response includes several actions: treat resources as limited but flexible; select only a few of the most promising economic opportunities; move investments accordingly; and be ready to quickly change focus if new opportunities arise.

At first glance, a larger cluster like financial services might seem to offer a better context for investment and support than a more specialized CSA. But the larger scale of a cluster increases the amount of investment required. The CSA is designed to generate rapid economic growth in a specialized domain. As it takes hold, the resulting interest and energy then ripple outward to the cluster and the broader economy.

As growth takes hold in a CSA, the resulting interest and energy ripple outward to the cluster and the broader economy.

Norway, one of Europe’s most consistently strong economies, used CSAs in this way to free itself from overdependence on fossil fuel exports. In 2019, the country funded 17 innovation research centers designed to attract businesses and innovation groups to the same locales, and thus spark the emergence of CSAs. Each center had its own specific focus, such as aquaculture, marine technology, hydropower, or sustainable farming—chosen based on its position at the intersection of existing economic activities and disruptive trends. For example, the aquaculture and sustainable farming themes aligned Norway’s larger agriculture cluster with several major disruptive trends: robotics, digital technology, environmental concern, health awareness, and the global geopolitical issue of food security.

In Philadelphia, on the east coast of the US, civic and business leaders recognized two of the city’s strengths: an extensive group of life sciences research centers based in local universities, and an established cluster of cold storage logistics companies in an enviable geographic location. Philadelphia is in the center of a 200-mile radius circle, extending from New York to Baltimore, with 46 million people and a robust network of shipping channels, air cargo services, railroads, and roadways. Philadelphia leaders worked together to establish a catalytic specialization area for temperature-sensitive logistics, order fulfillment, and transportation. This would make the city a regional logistics hub for two separate businesses. First, medical products and research materials, along with specialized computer devices, require sophisticated cold storage and transportation systems. Second, the same systems could also serve the growing market for refrigerated food and beverages, including products ordered online.

The benefits of a CSA strategy, compared to other growth approaches, include greater productivity and efficiency, similar to clusters. However, differently from a cluster strategy, a CSA strategy tends to have more potential for export success because they allow for trading in highly specialized goods and services. They also enable easier commercialization of viable but unfamiliar technologies and more powerful stimulus for innovation. The CSA strategy is particularly relevant for government policymakers seeking structural transformation of their existing economies. It fits well with another growth approach, the economic value proposition , in which a government defines in concrete terms how the country or territory will compete against others. As the CSA grows larger, its momentum helps carry the larger economic value proposition forward.

The government does not initiate or manage the CSA on its own. The agency begins by assembling all the economic players—including companies, regulators, and training and education providers—to talk about common growth goals. To achieve the CSA goals, the groups may have to pool their resources and raise their capabilities together. The effort may also require shifting some investment from other activities to the CSA.

A single national government might develop one or more CSAs at a time. To ensure that the mix of initiatives remains relevant for the economy, governments need to re-assess their selection and progress every three to five years. Because CSAs are smaller than clusters, they can be monitored more effectively, with faster feedback from real-world sales, export, and employment data. After a few years of support, if a specialization area does not bring about the expected benefits, policymakers can easily reallocate their efforts and resources.

How to Create a Catalytic Specialization Area

There are three steps for embarking on the CSA path: identifying clusters for possible CSAs, prioritizing high-potential CSAs, and developing growth models.

Identify Clusters for CSAs

The goal is to select potential economic clusters that might be starting points for CSAs. Look for narrow economic activities which emerge out of existing clusters, and capitalize on emerging trends.

Base your selection on relevant parameters, such as contribution to GDP, employment creation, export share, and positive impact for innovation and knowledge creation. The best measures will vary from one locale to the next, but they generally include the question of fit: Does it reflect your particular national aspirations? Some countries prioritize a more favorable export–import ratio. Others seek job creation, with opportunities that help the local population. Still others favor a better environmental footprint, or the advancement of high-tech and knowledge-based activity. Look at all the clusters in the light of your chosen parameters.

After identifying a select number of clusters, consider how they intersect with emerging trends in the economic, social, and technological spheres, among others. The BCG Center for Sensing and Mining the Future recognizes more than 100 trends which could be useful for this exercise. Look for trends that might increase supply or demand. For example, advances in data analytics have led to a new agritech specialization area within the agriculture industry. Include trends related to COVID-19 and the specialization areas that have been strengthened in response to the pandemic: telemedicine, artificial food, e-commerce, and biotech innovation.

Pay particular attention to the way trends combine. One example is the rise of “silver tourism:” travel and hospitality services for people over the age of 60, sometimes involving clinical procedures that are more expensive or unavailable at home. This CSA is a response to four trends: aging populations in developed nations, medical tourism growth, shortages of health care professionals, and easing of health regulations in many countries.

Prioritize Promising CSAs

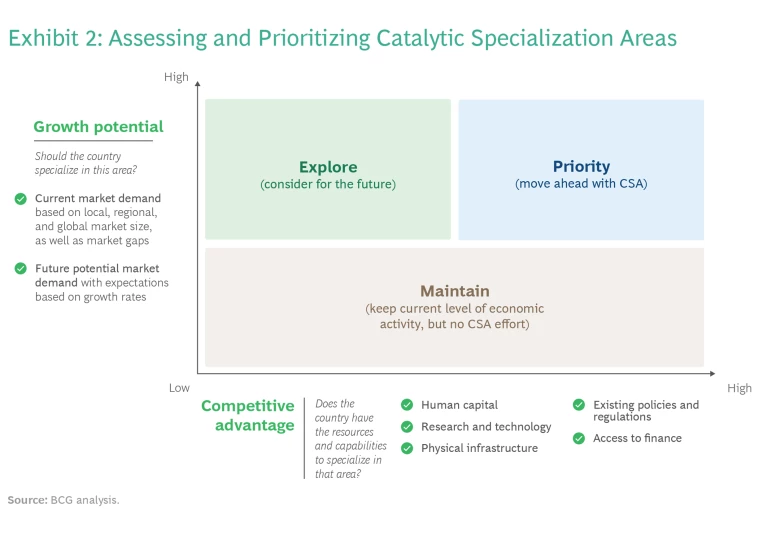

In this step, you assess the growth potential of CSAs identified in Step 1, and look at existing advantages in the broader economy. The goal is to generate a short list of catalytic specialization areas. As shown in Exhibit 2, there are two basic criteria: Growth potential of the CSA itself, and competitive advantage against other parts of the world. Based on the assessment, you either select each CSA as a priority now, explore its viability in the future, or maintain current activity in this sector, while holding back any CSA initiatives.

Growth potential, the first criterion, is related to demand: the size of consumer and business markets, now and in the near future. For example, London has established a CSA in low-carbon goods and services, with an estimated £7 billion market in related goods and services. When evaluating markets, consider not just domestic consumption but exports as well. It is difficult to grow a CSA without them. This is particularly critical for countries with a very small domestic consumer base.

Competitive advantage, the second criterion, is related to differentiation. Look for CSAs that would allow your country or city to stand out as more capable than others. In Canada, Calgary chose to specialize in agricultural innovation because of its unique access to a diverse landscape ideal for growing a variety of crops and raising livestock. To accelerate this activity, the provincial government established a program called the Smart Agri-Food Corridor, partnering with Olds University’s 2,800-acre agtech laboratory.

The optimal number of CSAs for your government to sponsor should be based on available resources: investment capital, infrastructure (including digital connectivity and transportation to your key markets), and human capital (the size and skill level of local talent). One rule of thumb is to select a number of CSAs based on population size and economic measures for the target area. For example:

- London’s population of ~8.9 million people and gross domestic product of ~$550 billion currently supports seven CSAs, including advanced manufacturing, life sciences, creative industries, agritech, clean energy and net-zero housing, fintech, and autonomous vehicle-based logistics.

- The Canadian city Montreal has about 1.7 million people and more than $134 billion in annual GDP. That’s enough for five CSAs: creative arts (particularly design and architecture), specialized medical equipment, AI and deep learning, logistics for the surrounding region, and cleantech, focused on renewable energy and energy efficiency.

- Smaller still is Calgary, a city in Western Canada of about 1.3 million people and ~$126 billion GDP. It supports three CSAs: energy transition technologies (evolving the oil and gas sector), agricultural innovation, and supply chain logistics.

Designing a CSA that is distinctive enough to succeed may be challenging. Bahrain and Oman are both investing in CSAs intended to position their city-states as logistics hubs. This is a natural aspiration, given their geographic position between Europe and South Asia, and their up-to-date logistics capabilities. Oman can even claim a 2,000-year-old history as a regional trade center. At first glance, this seems like a good strategy, but there may only be so many logistic hubs that the area can sustain. To succeed, these new CSAs may require further specialization to differentiate themselves.

When building out a CSA, leverage the existing strengths in your economy, such as proficient value chains.

Develop CSA Growth Models

In this third step, for each catalytic specialization area that you have selected, create growth models that will help you implement future development if and when the time comes. Tailor these to existing capabilities that you can apply and capabilities you expect to build. Establish milestones for CSA development, with dates assigned to each, that will help you track your progress.

It may take a few years for CSAs to become fully self-sustaining. Critical success factors vary from one CSA to another, but in general include talent development, business and investor outreach, financing, infrastructure upgrade, innovation and stakeholder coordination. For each factor, you can advance by identifying a desired goal, looking at the gap between current reality and that goal, and designing moves to cross the gap.

Each government follows its own CSA development path, but they all begin at a nascent stage, in which stakeholders from business, labor, and government collaborate on the launch of the initiative. Fortunately, there is much experience to draw on from countries that have already advanced along the path.

In moving along the path, balance aspirational goals with a healthy dose of pragmatism. Continue to leverage the strengths that already exist in your economy, such as proficient value chains. This will ensure that the economy can deliver on its new catalytic promises. One Montreal CSA focuses on creative industries such as design and architecture. This effort leverages the city’s assets in this domain: a high concentration of skilled professional artists, a wealth of specialized training programs, and the distinctive position of having been named a UNESCO Creative City of Design in 2006.

As you build out CSAs, maintain solid links to the competitiveness fundamentals of the economy. These are the mainstream engines of prosperity: talent, innovation, embedded knowledge, business and investor friendliness, tradeability (success in export markets), and quality of life. These fundamentals are needed to attract the skilled professionals who are often needed for CSAs to reach their full potential.

Some policymakers may feel daunted by the level of commitment that a catalytic specialization area entails. While it requires considerable effort, the process is engaging. Countries and cities that have fostered CSAs have found that, within a year or two, people notice an atmosphere of optimism. The area is not just grasping at any economic possibility. Its local citizens have chosen an economic identity: a body of work at which they excel. Gradually, the world pivots to recognize the value of what they are doing.

The CSA premise involves initial government effort in a way that catalyzes the skills and spirit of many stakeholders. As people get involved, a sense of opportunity permeates their thinking and soon becomes more evident in their shared culture. This combination of formal initiative and informal spirit turns out to make all the difference.