Authors’ note: Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has heightened geopolitical tensions and uncertainty. We believe that China will continue to be strategically important for MNCs and that the core analysis and recommendations in the article will remain valid and useful for many companies.

With the global economy in flux, companies must rethink their ways of doing business in China if they hope to keep current with the world’s largest contributor to GDP growth.

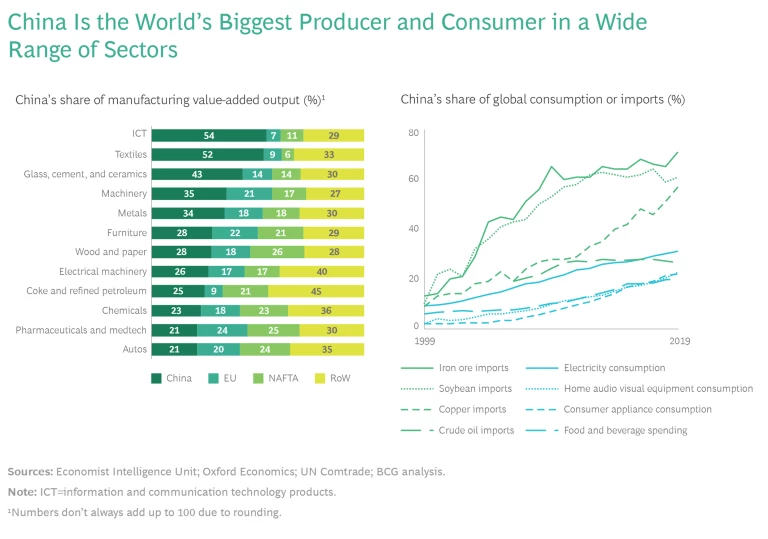

The COVID-19 pandemic has slowed China’s economic ascent, but the country remains on a trajectory that few global businesses can ignore. It is projected to contribute at least 25% of global growth for the rest of this decade and is on track to catch up with the US as the world’s largest economy in nominal GDP by 2030. Around 10 million people—roughly the population of Sweden—are joining the ranks of the affluent each year. China is the leading global market for most commodities and consumer goods, ranging from soybeans to cars, and the biggest user of e-commerce platforms. It’s the world’s largest manufacturer in a broad range of industries.

To succeed in China over the next decade—and effectively manage risks—international businesses need to craft more-sophisticated strategies.

The challenge for foreign companies is to capitalize on these opportunities at a time when the Chinese business landscape is shifting profoundly. Geopolitical, environmental, and social pressures are redefining international trade relationships. Consumer behavior is changing. Rather than primarily being a user and fast follower of new technologies, China is emerging as an important source of innovation in its own right.

As if navigating these changes weren’t difficult enough, China remains a land of complex contradictions. It’s a wealthy economic superpower at the leading edge of digital technologies. Yet with a per-capita GDP of less than $11,000, China still regards itself as very much a developing economy. Four decades of economic opening and reform have created vigorous competition and ample space for private enterprises and MNCs in many sectors. Yet the state retains extensive ownership of companies in key industries and the power to intervene and exert control in markets to ensure stability. China is also grappling with a host of structural challenges that will reshape the business environment for MNCs, including an aging population, wide income inequality, high levels of debt, and the need to find new drivers of growth in an economy that has been propelled by massive infrastructure investment and migration from rural areas to cities.

To succeed in China over the next decade—and effectively manage risks— international businesses need to craft more-sophisticated strategies. They need to recalibrate their engagement with China as a market, as a part of their value chains, as a source of innovation, and as a competitor in third markets.

A More Inwardly Focused Consumer Market

China’s National Statistics Bureau reported that retail sales rose by 12.5% in 2021 compared with 2020, after declining by 3.9% in 2020. However, many consumer service sectors, such as restaurant dining, entertainment, travel, and tourism, have not yet returned to pre-pandemic levels. The most recent outbreak in 2022 brings further uncertainty in consumption trends.

Foreign brands need to refresh their thinking on localization if they want to continue to meet Chinese consumers’ changing needs. Products, marketing content, and consumer engagement must all be tailored to local demand. Brands also require state-of-the-art digital solutions and features. Payments through mobile apps have become so commonly accepted, for example, that many taxi drivers in Shanghai no longer accept cash or credit cards. Brands also need to connect with local ecosystems and organizations and adapt management methods to local cultures.

The Shifting Trade Environment

China’s entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001 accelerated its takeoff as a trade power. The country now accounts for some 17% of global trade, compared with just 4% two decades ago. China’s export machine gained further ground during the COVID-19 pandemic, when it was fast to reopen its factories and became a critical source of medical supplies and consumer goods. But geopolitical frictions, the Chinese government’s growing emphasis on self-reliance in strategic technologies and industries, changing cost structures, climate change pressures, and the pandemic are now complicating the trade environment.

The trade relationship with the US remains fraught, raising speculation that the two economies could eventually decouple . Tariffs that the US and China placed on more than $200 billion of each other’s goods in 2018 persist, as do US restrictions on technology transferred to Chinese entities. China’s trade relations with other major economies are also becoming more complex, as illustrated by the escalation of tensions with Australia.

China’s government, meanwhile, has accelerated efforts to build robust domestic supply chains, distribution, and consumption to reduce the nation’s dependence on foreign technologies and markets. Indigenous Chinese standards and certification processes are becoming more prevalent.

Rapidly rising wages, as well as the aging of China’s workforce, are also influencing trade. Some production of labor-intensive goods is shifting to locations with lower wages or that are closer to customers in advanced economies. Yet though it may be receding as the “workshop of the world” in some sectors, China’s manufacturing future remains bright. It is still the world’s leading exporter—and the central link in global supply chains—in industries as diverse as electronics, textiles, and machinery.

Climate change concerns are yet another force that will redefine Chinese trade. The European Union, for example, is preparing to impose its Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, which will for the first time impose a levy for each metric ton of carbon dioxide emissions connected to goods imported into the 27-nation trade bloc. Other countries are considering following suit, which may lead to the formation of a “carbon club” with similar trade rules on embedded emissions. To avoid being at a competitive disadvantage in some of their most important markets, many Chinese manufacturers will have to work more aggressively to reduce their carbon footprint.

The Chinese government is also making the greening of domestic industry a high priority. To achieve its pledge to be carbon neutral by 2060, Chinese companies—with state support—are expected to intensify their work in fields such as electric vehicles, sustainable cities, and renewable energy.

China as a Growing Source of Innovation

As part of its effort to develop new drivers of economic growth, China is ramping up investment in R&D across a range of strategic industries. The nation’s 14th Five-Year Plan places a high priority on making China an innovation leader in fields such as biotechnology, quantum computing, semiconductors , electric vehicles, and robotics.

China is already starting to emerge as a source of innovation, in some fields rivaling the US and other advanced economies. Huawei accounts for 38% of global 5G patents, for example. And China is regarded as a global leader in artificial intelligence: a BCG survey of 2,700 AI managers found that 32% of Chinese companies were actively adopting AI applications, compared with 22% of US companies. A further 53% of Chinese companies had piloted AI applications. Giant Chinese companies such as Alibaba, Tencent, and Baidu, meanwhile, have been leading innovators in digital e-commerce , payments, and content delivery.

China has been steadily closing the gap with the US in terms of total R&D spending. Although China still lags the US in basic research, its government is significantly increasing investment in scientific discovery. Chinese government agencies and industry together spend more than the US on development research , which focuses on translating new knowledge from basic and applied research into commercial products and new manufacturing processes. While much of this R&D is aimed at building advantage in China’s domestic market, we believe it will make China an increasingly important source of innovation globally and a magnet for R&D capital. The Chinese Greater Bay Area, which includes Guangdong province, Hong Kong, and Macau, accounted for $313 billion worth of high-tech investment between 2017 and the first half of 2020, for example, compared with $231 billion for the San Francisco Bay Area.

MNCs are also increasing their investments in Chinese innovation centers for products and solutions aimed at global markets. Since 2020, for example, BMW has launched an innovation center in Shenyang to develop high-voltage batteries and a startup incubator in Shanghai with Alibaba focusing on Internet of Things solutions for vehicles. Roche recently established a center in Shanghai devoted to drug discovery and development and another for accelerating startups; ABB opened a 50-engineer innovation center working on AI, cloud, and smart building solutions. (See the exhibit.)

China Inc.’s Rise as a Direct Global Competitor

More than 120 Chinese companies are on the Fortune Global 500 list—compared with just nine 20 years ago. These massive companies tend to generate the bulk of their revenue in China’s large domestic market, especially in “pillar” industries such as energy, finance, telecommunications, and utilities. But a growing number of Chinese companies are developing truly global footprints. Some, such as consumer durable goods maker Haier, began this process in the 1990s, when the government loosened regulations and coordinated incentives under the so-called zouchuqu (“go out”) strategy. Haier now earns nearly half its $30 billion in revenue overseas. Others include the acquisitions of IBM’s PC business by Lenovo, Swiss agrochemical company Syngenta by ChemChina, and Volvo Cars by Geely. Some new companies are also having initial success competing in global markets. The B2C fast fashion e-commerce company Shein, for example, has become a truly international player. Shein is expanding its footprint to the US, Middle East, Europe, and Southeast Asia.

MNCs are facing strong Chinese companies not only in emerging markets but increasingly in their highly profitable home markets as well.

Chinese government support, be it preferential financing or facilitation of infrastructure contracts through its Belt and Road Initiative, plays a part in enabling overseas expansion. So does the critical mass that Chinese companies have built in their home market. But it’s also true that Chinese companies are already offering globally competitive products and services in a range of industries, including construction machinery, telecom equipment, mobile handsets, and passenger cars. Their products are proving particularly successful with price-conscious consumers in emerging markets. Chinese companies are also starting to invest in developing intellectual property, after-sales services, and other capabilities that are needed to better compete in advanced markets such as the US and EU.

MNCs are therefore facing strong Chinese companies not only in emerging markets but increasingly in their highly profitable home markets as well. This competitive challenge is sure to grow in the years ahead.

Four China Strategies for the 2020s

To succeed and manage risks in light of the structural shifts we’ve described, many MNCs will need to refine their approaches to China. Here are four key strategies:

- Embrace an “in China for China” strategy. MNCs can no longer rely entirely on the luster of their global brands to win and retain loyalty among Chinese consumers. They must increasingly introduce products and go-to-market strategies tailored to the tastes, preferences, and needs of target consumer segments. They must meet the growing expectation among Chinese consumers for quality and calibrate the right degree of localization, based on their particular technology, intellectual property, and market position. MNCs must also learn to win in China’s digital realm. They must build a competitive presence on one or more consumer-facing e-commerce platforms, become more sophisticated in using those platforms to reach out to those consumers, and deliver goods and services with flawless execution.

- Re-evaluate global value chains. With trade tensions seemingly chronic, companies should reassess their manufacturing and sourcing footprints in light of higher tariffs and expanding non-tariff barriers. For some goods, production capacity in China dedicated to exporting to the US can be reoriented to serve China’s growing domestic market or neighboring markets in the Asia-Pacific region that have more favorable trade terms. For products whose rising labor costs alter the economics of supplying distant markets from China, companies should consider more regional supply chains in which more goods are produced in low-cost locations closer to end users. As tougher climate-related regulations such as the EU’s carbon border adjustment mechanism come into force, global companies will also have to account for the costs of carbon associated with goods produced in China. In many cases, environmental pressures will create new opportunities for MNCs with advanced green technologies and processes, as well as expertise in accounting for emissions, to help their Chinese partners and suppliers become more carbon efficient.

- Use China as a source of innovation. As China’s indigenous R&D and product innovation capabilities grow, more MNCs need to shift their focus from “transferring” technology to Chinese partners to absorbing new know-how that can be applied globally. MNCs certainly have much to learn from leading Chinese business process innovations, such as in their “last mile” strategies for delivering e-commerce. Increasingly, they are likely to find that Chinese partners can be valuable providers of intellectual property in fields such as AI, blockchain , and Industry 4.0 manufacturing processes. MNCs opening new innovation centers in China will, of course, have to consider IP protection and compliance with technology-transfer regulations of their home countries. But the benefits of developing bespoke offerings at the cutting edge of technology for China’s increasingly affluent consumers often outweigh the risks and can generate immense value.

- Hone global competitiveness with Chinese companies. Responding to the Chinese challenge in strategic markets will require a comprehensive strategy and proactive mindset. MNCs need to make strategic decisions about which markets to compete in—and how. In certain emerging markets where Chinese companies are seizing market share and winning the loyalty of future generations of middle-class and affluent households by competing on price, MNCs may need to focus more on introducing products that are affordable and attractive and that meet the needs of emerging-market consumers. They might even consider partnering with other Chinese companies that seek to crack into those markets. In developed markets, MNCs will need to protect their existing share more aggressively.

Succeeding in and with China has always been one of the toughest challenges for global companies. Yet even as a new set of challenges emerge, the fact remains that China is more strategically important than ever—as a market, as a supplier, as a source of innovation, and as a global partner or competitor. We believe that companies that understand the structural shifts underway in China—and adapt their strategies accordingly to new realities—will be able to capture the immense growth opportunities generated by this rising economic superpower.