Companies are making bold commitments to improve ESG performance. But to successfully deliver on their goals, they must steer clear of these common challenges.

Companies across industries and regions increasingly see sustainability as a critical driver of competitive advantage. And many are setting audacious sustainability goals—reflected in concrete environmental, social, and governance (ESG) targets—including commitments to reach net zero, moves to ensure humane practices and living wages for people along their supply chain, and pledges to expand diversity, equity, and inclusion. The challenge: most are struggling to translate their goals into action. According to a recent survey of board members by BCG and the INSEAD Corporate Governance Centre, the top barrier to improving company ESG performance is the inability of the organization to execute.

What are the factors blocking effective corporate mobilization to deliver on ESG goals? On the basis of our extensive work helping companies improve the sustainability of their businesses, we have identified six common pitfalls organizations must avoid to ensure that their ambitious targets become a reality:

- A Weak Commitment at the Top. Senior leaders do not display a strong, visible, and consistent commitment to the sustainability agenda, limiting credibility with internal and external stakeholders.

- The Perpetual Chief Sustainability Officer. The company appoints a CSO with no plan to transition ownership to the business, limiting ownership of and accountability for sustainability outcomes among the organization’s leaders. CSOs can be a great catalyst for progress, but companies need to plan for the role to evolve.

- Commitments with No Accountability. Performance management, including executive compensation, is not tied to sustainability outcomes, so long-term sustainability goals lose out to near-term financial performance.

- Coordination Problems. The role of the central sustainability team versus the business units is not clearly defined, resulting in disorganized execution and slow progress toward goals.

- A Failure to Embed Sustainability in the Business. Sustainability is not a mandatory or material consideration in business processes, limiting employees’ ability to make decisions aligned with sustainability goals.

- Talent Gaps. Companies fail to anticipate and act on the fundamental shifts in skills and capabilities required to deliver on their sustainability agenda.

The right approach to executing a sustainability strategy for an individual organization depends on a number of factors, including the company culture, the industry, and the issues that are material for the business. Overall, however, all organizations should keep these six pitfalls in mind as they hone the operating model to deliver on their sustainability ambitions.

A Weak Commitment at the Top

The absence of credible support for sustainability from senior leadership is one of the most common challenges we hear about from sustainability leaders and practitioners. One former executive at a large multinational oil and gas company points to a lack of leadership commitment as one of the primary stumbling blocks his team faced when rolling out the company’s sustainability strategy. “Strong commitment from top-level leadership is a key determinant of success or failure of ESG initiatives,” he notes. “When there is top-level management support, it makes a night-and-day difference.” And the data backs this up: surveys consistently find that executives cite a lack of senior-leadership support as one of the top barriers to progress on sustainability.

The absence of credible support for sustainability from senior leadership is one of the most common pitfalls.

Leaders can demonstrate their commitment to building a sustainable advantage in a number of ways. Executives at top sustainability performers often establish themselves as thought leaders in the sustainability space through publications and talks on the topic. They also work to drive industry- or society-wide change outside the four walls of their company by participating in sustainability-focused coalitions.

Just as important as external engagement is how leaders communicate internally about sustainability. Executives at companies recognized for their sustainability leadership speak to their employees frequently about the sustainability agenda. They spread a consistent message highlighting the links between the company’s sustainability goals and its mission, vision, and strategy, underscoring how sustainability connects to corporate purpose and helps create business value. This demonstrates a credible, authentic commitment.

The Perpetual CSO

Many companies appoint a dedicated leader to oversee the sustainability agenda. Although a CSO can create focus and momentum on sustainability early in an organization’s journey, the most effective companies understand that the role should evolve over time.

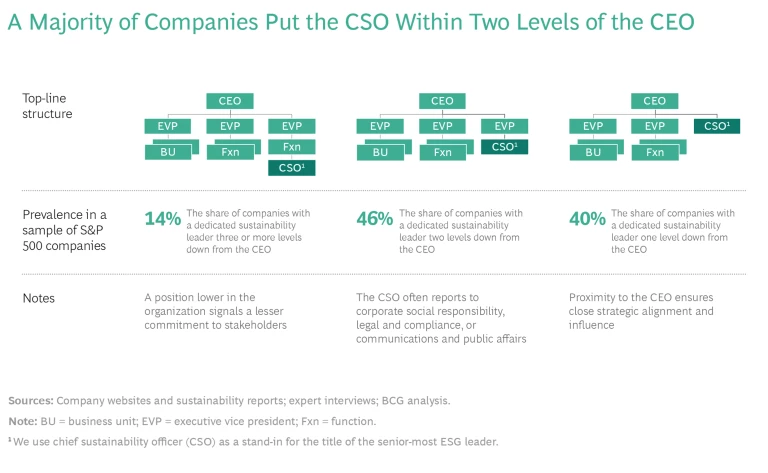

In a sample of S&P 500 companies, we found that a majority (roughly 80%) have appointed a dedicated sustainability leader. And most of them have given the CSO the authority required to be a true catalyst for change, with about 86% placing that person within two levels of the CEO in the organization chart. (See the exhibit.)

The early creation of the CSO role provides a source of sustained focus to drive the sustainability agenda and harmonize efforts throughout the organization. As the former CSO at a multinational consumer company notes, “You need the hammer to drive the nail. You need someone at the center to force the issue and get the training wheels on before you move to a more embedded model.”

That role, however, should shift over time. If the CSO remains separate from the core business, business unit leaders may have a tendency to offload responsibility for sustainability goals to that sustainability leader. Although the role is an important catalyst for change, it is no substitute for business-led accountability where every part of the organization plays a part in delivering on the sustainability strategy. “There needs to be distributed accountability for sustainability,” says one former consumer company CSO. “It’s about empowering the functions and geographies to internalize the values of a long-term multistakeholder business model. I used to joke that my job was to work myself out of a job.”

Some companies accomplish this transition by changing the CSO position to a dual role as the company’s sustainability efforts become more advanced, with the leader of a business unit driving a critical sustainability initiative taking on the additional role of CSO. This ensures that business leaders are accountable for sustainability outcomes and incorporate sustainability into their business objectives and decision making. At one large food manufacturer, for example, the head of sustainability also oversees procurement, a function that has a close link to the company’s ESG performance given the scale and reach of the company’s supply chain. Meanwhile, the managing directors for each country at a multinational home goods company also act as the CSO for that country.

Commitments with No Accountability

Companies struggle to deliver meaningful results when they do not establish clear accountability for sustainability goals and initiatives. This is one of the trickiest things to get right, particularly early in the journey.

In organizations at a less mature sustainability stage, a core group of leaders are often assigned accountability for meeting specific enterprise-wide sustainability goals. For example, if a key objective is to reduce the overall plastic waste that the company creates, the head of plastics may initially be responsible for meeting circularity targets. Over time, that evolves toward a more distributed model. Advanced companies break down enterprise-level sustainability goals into quantified, near-term targets at the business unit and function level. The result is clear KPIs for every business that ladder up to overarching company sustainability goals.

Clear accountability for goals is necessary, but it’s not sufficient to successfully operationalize sustainability strategies. The area where companies most often fall short is tying performance on key sustainability indicators to compensation. Without incorporating sustainability measures into performance and incentives, the longer-term sustainability goals frequently lose out in favor of near-term financial performance. One leader at a large oil and gas company recalls the struggle to get sustainability metrics incorporated into executive compensation: “Without compensation incentives beyond short-term business objectives and P&L numbers, there was no incentive for anyone to do anything on sustainability.” Unfortunately, the data suggest that this experience is relatively commonplace. Just over half of companies in the S&P 500 use some form of ESG metrics to set incentive compensation, according to research by Semler Brossey.

For accountability to be effectively hardwired, the most material sustainability targets should be incorporated into compensation and weighted meaningfully compared with financial metrics (as much as 25% to 30% of annual bonus and long-term incentive pay). Corporate sustainability leaders don’t stop at embedding sustainability metrics into executive compensation but cascade incentives further down in the organization as well. For this to work, employees with compensation tied to sustainability need to understand how their work impacts sustainability goals and be empowered to raise issues and influence decisions.

Coordination Problems

Because sustainability teams are typically relatively small (fewer than 50 people in many cases), the “boxes and lines” of organization structure are not very complicated to design. What companies find more challenging, however, is clearly defining the roles and responsibilities of the central sustainability team and the business units. Given that sustainability goals often require considerable cross-functional coordination to achieve, confusion over which part of the organization is responsible for which activities can create overlapping remits and slow down progress. According to a recent survey conducted by Russell Reynolds, C-suite leaders cite organizational complexity as one of the top barriers to embedding sustainability across business strategy.

A case in point: a multinational beverage company struggled with a disorganized and decentralized sustainability effort. Sustainability roles existed throughout the organization as well as in a corporate center of excellence, a supply chain center of excellence, and the business units. Individual functions invested in their own sustainability capabilities, even when those were essential to other parts of the business as well. The subject matter expert on recyclable packaging, for instance, sat within and served the procurement function and was not accessible to the marketing teams in the business units that wanted to consider circularity in the design of new products. This resulted in confused execution and duplication of resources throughout the organization.

We have observed three commonly used models that create clearly defined roles and responsibilities and help companies avoid these executional challenges:

- A Center of Coordination. At the early stages of their sustainability journey, companies often deploy this model, creating a lean central sustainability team. The group works with executive leadership to develop the sustainability strategy, set goals and targets, and advance the initiatives needed to reach their targets. The central team’s primary focus is coordinating the initiatives across the business to ladder up to a coherent sustainability strategy. It may also provide light-touch data management, reporting, and communications support. Sustainability-affiliated staff in the business units (who may be dedicated to sustainability only part-time in many cases) execute the sustainability initiatives.

- A Center of Support. As a company’s sustainability effort becomes more mature, the sustainability function is frequently organized into a moderately sized central team with small satellite groups embedded in the business. The central team is responsible primarily for activities that support the corporate sustainability agenda, including data management, reporting, communications, and external partnerships and advocacy. In addition, it may incubate sustainability initiatives that require new technologies or capabilities. The embedded sustainability teams and business leaders work together to set a sustainability strategy for the business units that is aligned with the corporate strategy and to design and execute the initiatives required to meet business-level targets.

- A Center of Expertise. Another common model among mature companies is the establishment of a central sustainability team that serves as a center of expertise. This group houses subject matter experts who can help business units design and execute sustainability initiatives (the development of new products or packaging, for example). Certain key activities such as data, reporting, communications, and partnerships continue to be centralized, although these responsibilities are frequently embedded within other teams in the corporate center such as finance or corporate communications. Some companies maintain sustainability-focused teams in individual business units and functions to help leaders set the sustainability strategy for the business and design and execute projects aligned with that strategy. The need for dedicated teams diminishes, however, as employees across the business learn to apply a sustainability lens to the decisions they make.

A Failure to Embed Sustainability in the Business

Companies falter when they do not incorporate sustainability considerations into day-to-day business processes and decision making. This can reinforce the perception that sustainability is the sole remit of the central sustainability team and can hinder the ability of the workforce to make decisions aligned with the company’s sustainability goals. A former executive at a multinational home goods company points to its move to build sustainability criteria into all business cases as “the single biggest factor that changed people’s mindset.”

The most effective companies integrate sustainability performance into regular business performance reviews. They treat sustainability goals as inseparable from (or at least closely linked to) business goals and discuss sustainability progress in the same forum and format as they discuss business progress. To make this work, organizations reconfigure regular business reviews to include a discussion of both financial and sustainability KPIs and targets; business leaders model the commitment to sustainability progress by proactively asking their teams for updates on sustainability performance; and companies incorporate key sustainability KPIs and metrics into business performance dashboards to give executives regular visibility into progress.

The most effective companies integrate sustainability performance into regular business performance reviews.

Industry leaders also rewire key business processes, such as business planning, capital expenditure decision making, M&A, and product development, that create the biggest sustainability impact. This often requires a substantial shift in the corporate mindset about how decisions are made and how value is evaluated. The company’s sustainability goals serve as a helpful roadmap to identifying the processes with the greatest impact. For instance, organizations focused on reducing Scope 3 emissions (external emissions that occur along their value chain) will likely need to rework their procurement processes, while those aiming to drive growth through sustainable products will need to revisit their product development processes.

Companies that are serious about making a substantial sustainability impact weigh metrics related to environmental or societal impacts on par with financial measures in decision making. The specific metrics incorporated often vary according to the nature of the organization’s goals. For example, many companies implement some form of internal carbon pricing to ensure that sustainability is embedded in the evaluation of investments. The front-runners in this space are beginning to think about how to price other externalities of their business, such as impacts on biodiversity and water resources. As the home goods executive puts it, “If you weight sustainability goals as much as business goals, then you have a fighting chance of making progress.”

Talent Gaps

Companies placing sustainability at the center of their strategy must ensure that they have the workforce and capabilities to deliver. Many organizations struggle to identify the skill shifts required to deliver on their sustainability agenda in the near and long term. This is particularly important because recent studies suggest that the demand for talent with sustainability skill sets will soon outpace supply, putting businesses that have not invested in the requisite talent and capabilities at a

While companies need some basic sustainability fluency throughout their business to support the sustainability agenda, they must also plan for the fundamental capability shifts that sustainability strategies often engender. New business models, products, and services may require entirely new skill sets and competencies that the current workforce does not possess. When addressing this challenge, organizations must work backward from their sustainability goals. With clearly defined targets and a roadmap of initiatives needed to deliver on those targets, companies can determine the skill sets needed to accomplish their objectives. Then they can conduct a capability assessment to determine the extent to which the organization possesses the requisite skills. This evaluation will yield a clear picture of what skills gaps exist, and leaders can determine how best to fill those gaps, whether that means upskilling or reskilling the existing workforce, acquiring new talent outside the organization, or partnering with external organizations.

Companies placing sustainability at the center of their strategy must ensure that they have the workforce and capabilities to deliver.

For example, many financial institutions are designing new products to meet the demand for environmental and social impact–oriented investment vehicles from their customers. These product innovations require the front-line sales teams to be able to consult knowledgeably with customers on related sustainability topics, including gaining an understanding of customer needs and describing product options and benefits. Financial institutions at the forefront of sustainability transformation are investing in broad-based upskilling for their sales teams to build these capabilities.

Alternatively, companies may need to acquire entirely new types of talent through hiring or partnering externally to access specialized skill sets. A mining company, for example, is recruiting talent with a deep understanding of green energies such as hydrogen power to drive decarbonization innovation within the organization. It is also partnering with research institutions at the vanguard of sustainability innovation to develop sustainable-manufacturing techniques.

Corporate leaders increasingly understand that sustainability is an essential element of building competitive advantage. Avoiding the pitfalls outlined above helps ensure that companies are on the right path toward delivering on critically important sustainability goals.

As companies begin this journey, they can foresee and avoid potential challenges along the route to successful activation of their sustainability strategy by answering some key questions:

- Do our senior leaders exhibit a visible and vocal commitment to our sustainability agenda? Can they articulate how our company builds sustainable advantage?

- Have we put the right accountability mechanisms in place to ensure that our business and function leaders take ownership of sustainability outcomes?

- Is sustainability built into our compensation structure in a thoughtful and material way?

- Do we have a clearly defined interaction model between the central sustainability team and business units?

- Have we made sustainability an essential element of our core business processes? Is it an integral part of our decision making?

- Do we have the will and skills to accomplish our goals? Are our employees engaged in our ESG mission? What capabilities do we need to build?

The answers to these questions will reveal where gaps exist in a company’s sustainability efforts—and can be the key to ensuring that ambitious goals become a reality.

The authors thank Nuwan Rajapakse for his assistance in the research and development of this article.