It took COVID-19, a deadly global pandemic, for the US to wake up to the gaping fault lines in the “care economy.” What is the care economy? It is a vast ecosystem where families, employers, and institutions—from daycares and nursing homes to schools and hospitals—come together to support the young, the old, and the sick. This support is necessary for the functioning of a healthy society, and this work underpins every part of the economy. We can ignore it no longer.

The Disorganized Care Economy

The stories are everywhere. Take Joanne, an environmental consultant with a master’s degree and full-time job in the Denver oil-and-gas industry, who pared back her work to ten hours a week because she couldn’t find childcare for her baby son, Miles. Her first nanny slept on the job, she says, and a second chose to work in a school for more pay and benefits. Miles couldn’t land a spot in daycare. Joanne is married and her husband has a stable job, but when she reduced her work hours to care for Miles, the family’s income was halved.

Or consider Naila, a registered nurse since 2013 in San Francisco, who worked 12-hour shifts three times a week. She quit five months after her first baby was born, nudged by the local daycare’s hours of just 8 a.m. to 3 p.m. Although her family can live on her husband’s income, she regrets leaving nursing, a profession she loves and one that desperately needs experienced staff. Still, Naila doesn’t plan to return to nursing until her child is at least five. Then she’ll probably look for a medical clinic with shorter shifts.

Sandra engaged her mother to help with her two kids while she continued her career as a talent recruiter. Then her 77-year-old mom got sick, and Sandra had to quit her job to look after all three, moving into the increasingly common unpaid role of caring for both children and parents.

These stresses—at the nexus of family and work—play out millions of times a day in the US, affecting us all. They expose a fundamental mismatch in supply and demand for care services in the world’s biggest economy. And the consequences are significant and growing. Already, the US birthrate has dipped below replacement rate as potential family builders hold off having children, often citing the cost and availability of childcare and the quality of public schools. At the same time, the demographic bulge of aging baby boomers and the reality that more people are living into their 80s and 90s puts enormous pressure on senior-care systems. In every case, technology, efficiency, or new facilities can only go so far; the care economy requires present, skilled, compassionate human labor.

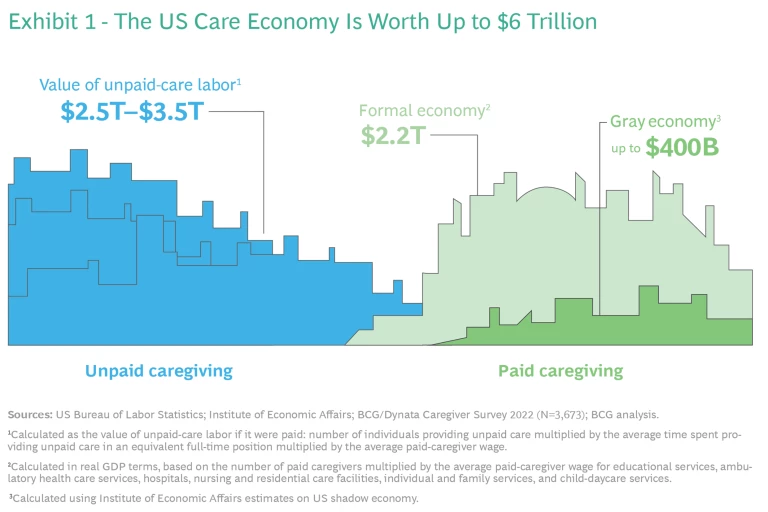

In a May 2022 report, we estimated the size of the care economy, including both unpaid and paid caregiving, at up to $6 trillion, approaching a quarter of total US GDP. (See Exhibit 1.)

This segment of the economy is expanding very fast but remains precarious, with little coordinated action so far to address gaps and organize comprehensive solutions. Now, we’ve quantified what these gaps in the care economy cost the US in GDP every year.

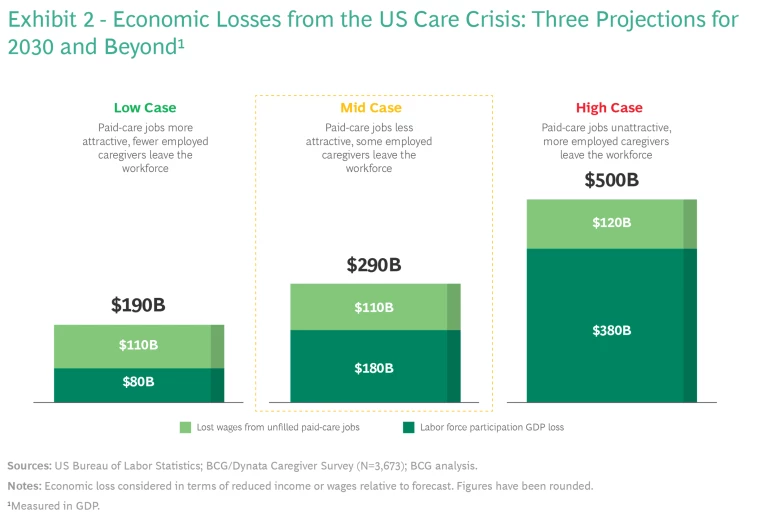

We forecast that the US will lose about $290 billion a year in GDP in 2030 and beyond if we fail to fix two critical care-economy dynamics: (1) the lack of available workers to fill a dramatically increasing number of these hands-on jobs, and (2) the departure of productive employees from the paid labor force to take on unpaid-care duties, whether they want to or not. That economic loss is equivalent to losing half of the annual GDP growth projected from 2022–2023.

The care crisis is tied to the market for hourly labor—significantly, low-wage labor—and, therefore, intersects with the postpandemic “great re-enrollment” and a US unemployment rate hovering below 4%. About 1.8 million critical-care jobs, including nursing assistants, home health aides and childcare workers, are open, according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. And the demand for these jobs is poised to grow in the next ten years, well beyond these vacancies. However, these roles generally pay less than $18 an hour and offer poor benefits. Workers are required to be onsite, with inflexible hours and unexpected overtime. Training is inadequate; turnover is high. It’s no wonder these positions are starved for applicants.

Ample openings in industries that compete for the same workers, such as

retail

and

hospitality

, exacerbate the problem, and are already drawing away current care-economy employees with better pay, perks, and easier duties. That’s evident in the numbers: as of July, pandemic-related job losses across the broader economy had largely recovered, but job totals in child-care services were still 8% short of prepandemic levels, according to the Center for American Progress.

For CEOs and other leaders, understanding the magnitude of the care economy and its current dysfunction is critical to grappling with labor shortages and broader talent concerns. Care workers require competitive, livable wages. People who hire care services in order to do their jobs in other industries require support. Failing to recognize the childcare and eldercare responsibilities of millions of US workers saps productivity and job satisfaction.

Fixing the care problem in the US now isn’t just good business, it’s necessary business.

Quantifying the Care Crisis

Care activities are critical to GDP growth because they support workers in every other industry. Still, economists, investors, and corporate executives have long overlooked this labor, both because it straddles the informal economy and because it has been derided as “women’s work.” But care is too important to a healthy US economy and stable society to neglect. Most other countries have addressed workers’ care needs more deliberately. One dramatic example is the issue of paid leave: the US is the only developed country that doesn’t mandate paid time off to support employed women in the days after they give birth. Bonding with a newborn and recovering from pregnancy are fundamental to the maternal experience, yet we still don’t guarantee income in this period of a working woman’s life.

About 56% of US workers—roughly 90 million people—have care responsibilities outside of their full-time jobs, according to a proprietary survey of more than 3,600 employed caregivers conducted by BCG and Dynata, our coding and sampling partner. (See the methodology .) Approximately 40 million of these caregivers rely on paid care—such as nannies, daycares, or nursing homes—to go to work, meaning that when paid care falls through, they are at risk of missing work or leaving their paid jobs altogether. The remainder rely on unpaid care, including family, friends, neighbors, and others, or do it all themselves. (See “Overview of the Care Economy.”)

Overview of the Care Economy

- Unpaid Caregivers. Anyone with unpaid-care responsibilities for children, adult family members, or both, whether they themselves are employed.

- Employed Caregivers. A subset of the first group—workers in the broader economy who also have unpaid-care responsibilities, for children, adult family members, or both.

- Paid-Care Workers. Individuals who provide care as their occupation. Many care workers are also employed caregivers with unpaid-care responsibilities. Many of them also rely on paid-care workers for their own family members.

In 2030 and beyond, the US is expected to lose around $290 billion in GDP a year as a result of the care crisis. Our estimate comprises two parts: First, it includes the lost wages because so many care jobs are unfilled. Second, it includes the effect of reduced labor force participation because of care shortages—that is, people like Joanne in our opening example, who cut back on her paid work in the Colorado oil-and-gas industry to take on unpaid-care work.

This figure is a mid-case estimate based on averages of the last ten years. In three different scenarios in Exhibit 2, we see a range of GDP-loss outcomes based on the relative “attractiveness” of care sector jobs. On one end, improving the quality-of-care jobs would filter through the system by attracting and retaining more workers, and therefore make better care services available to all. On the other end, more people leaving care jobs and fewer options for people looking to hire care workers has dire consequences.

The mid-case scenario—the $290 billion loss—rests on the following assumptions: Care jobs fill at the average rate since 2012, resulting in a care-worker shortfall of about 14% by 2030. About 20% of workers who can’t find adequate care leave the workforce to fill the care gap at home.

In a more optimistic scenario—with a projected loss of about $190 billion a year in 2030 and beyond—care jobs fill at the highest rate they have in the last ten years, and the care-worker shortfall is about 13%. Roughly 10% of employed caregivers leave the workforce if their paid care falls through.

Care workers and care jobs are truly essential. They enable our employees to productively show up at work, knowing that their children, parents, loved ones are well taken care of. Without them, we will lose valuable, trained, and passionate workers and won’t be able to fill and keep filled the jobs we need to thrive both as individual companies and as a country. Filling paid-care jobs isn’t just an issue for governments, it needs to be top of mind for CEOs and executives too—we can help solve this. — Rich Lesser, Global Chair and former CEO, Boston Consulting Group

On the other end—with a projected loss of about $500 billion a year—we modeled the relative attractiveness of paid-care jobs at the lowest level seen over the last decade. In this case, a 15% vacancy in paid care ensues. And 40% of employed caregivers leave the workforce if their paid care falls through, even those worried about the loss of their own income.

These scenarios are useful for examining the magnitude of the US care problem in the coming decade. But even these large dollar amounts don’t tell the whole story. Societal hardships—including stress and strain on those juggling demanding jobs and managing both childcare and eldercare—are common. Nearly 60% of employed caregivers in our survey said they struggle with their mental and physical health and with productivity and burnout.

Interlocking Solutions

The care economy transcends traditional business boundaries, and smoothing the path for workers, companies, and the economy overall requires interlocking private, public, cultural, and individual action. Our study shows that a small change in the relative attractiveness of care jobs makes a big difference in the effect on lost GDP. So, thoughtful, targeted changes may have an outsized effect on the problem. That is: there is hope.

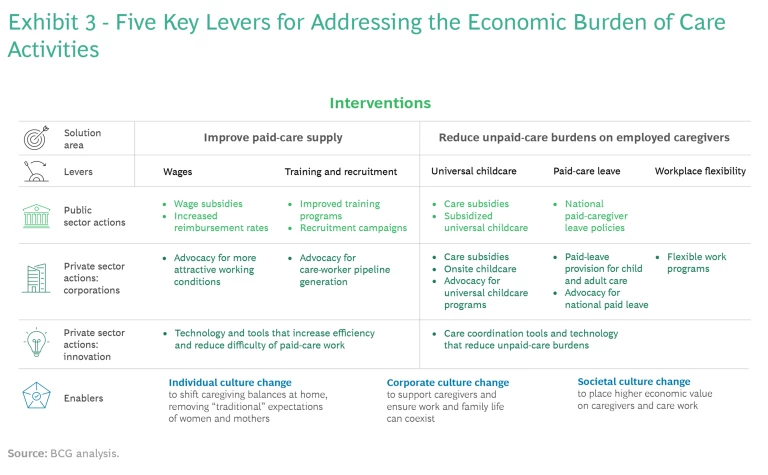

Our suggested solutions start by (1) addressing the supply of paid-care workers and (2) helping relieve the care burdens that prevent able persons from fully engaging in paid work or, in many cases, forces them to quit their jobs. (See Exhibit 3.)

Boost Care Supply

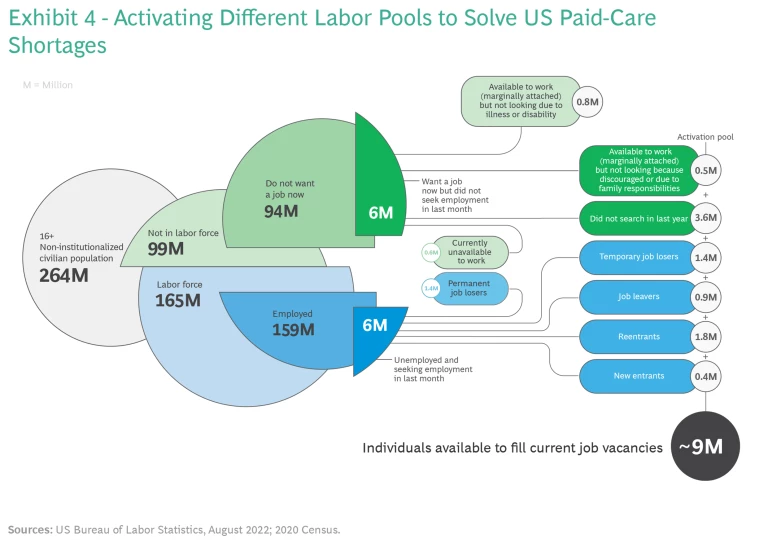

We have enough working-age individuals in the US to fill the 1.8 million (and growing) vacancies in care jobs. According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, about 9 million individuals could be activated to fill roles, including home health aides, nursing practitioners, and personal care workers, which are projected to be among the fastest-growing occupations of the next ten years. (See Exhibit 4.)

These are people currently on the sidelines, including those who report that they aren’t working because they have family responsibilities, are discouraged by their job prospects, or are recently out of a job and in the market for a new one. Of course, care jobs have to become attractive enough to entice people to come into the workforce. And, in many cases, these people also need to find the support to meet their own care responsibilities.

We must also adjust expectations of who participates in this work by destigmatizing care jobs as “women’s work.” About 80% of paid caregivers today are women, but men are equally capable in these roles. Additionally, some community-care jobs—such as afterschool programs—may suit retirees who don’t want full-time positions. Adjusting what we consider “working age” is worthwhile, especially as the population ages and healthy older Americans thrive with such social engagement.

Cross-generational care for one another—teens interacting with septuagenarians, for instance—is a virtuous circle. It’s happening elsewhere. In the Netherlands, for example, university students can live free in nursing homes in exchange for 30 hours a month of providing company to elderly residents or teaching skills such as how to use social media.

Selective immigration programs for qualified health care workers can also bridge gaps in paid care beyond the current US labor supply. Such programs are underway in other countries but haven’t been tried in the US. For example, Canada launched the five-year Home Child Care Provider Pilot and the Home Support Worker Pilot immigration programs in 2019, letting individuals working in childcare or home-support professions apply for permanent residence.

Filling all those care jobs, of course, would also provide the compounding advantage of unlocking talent to fill the labor shortage in other sectors across the economy.

Increase Wages

To boost supply, care jobs need to be more appealing and valued, starting with higher wages. The average hourly pay of a US caregiver is less than $14. That compares with $19 an hour, on average, for entry-level work at Amazon.

One barrier to boosting caregiver wages is who is footing the bill. In the majority of childcare cases, families pay individuals or centers, and the after-tax expense can be overwhelming. Parents of infants and toddlers spend about 10% of their income on childcare today, despite the US Department of Health and Human Services recommended spending cap of 7%.

In eldercare, raising pay is related to reimbursement rates from government entities, especially Medicaid, the primary source of funds of long-term services and support for older adults. These reimbursement rates anchor the salaries for home-care and nursing-home workers—low reimbursement rates result in low wages. Some governments have already considered this. In 2021, Oregon introduced an enhanced wage add-on program, increasing Medicaid reimbursement rates to home- and community-services providers and nursing facilities by 10% and 4% respectively. With this program, the state was able to mandate minimum wages for home-care and nursing-home workers between $15 and $17 per hour, with increases over following years.

The economic argument for increasing adult-care wages is strong. A City University of New York study estimates that paying home-care workers between $30,000 and $40,000 annually depending on the city (vs. the current $22,000 median) could generate $3.6 billion in economic savings across the state.

Improve Training and Recruitment of Paid-Care Workers

Some states already are shifting the narrative around caregiving careers, branding them both essential and rewarding. They’ve revamped training programs, employment portals, and recruiting campaigns. Arizona, for instance, is offering personalized career maps and connections to training and testing centers and is sponsoring shared worker stories. Maine budgeted $20 million to promote health care jobs in 2022, with $1.5 million dedicated to recruiting campaigns. Generally, states should opt to both actively recruit caregivers to their workforce as well as make training programs more easily accessible. They can do so by providing online options in multiple languages and offering career-pathway sites to help prospective caregivers understand job progression over time.

In our research, a few sessions on child development increased caregivers’ job satisfaction because they taught them how to better do their job; in particular, how to handle difficult situations with groups of children. — Myra Strober

Relieving the Unpaid-Care Burden

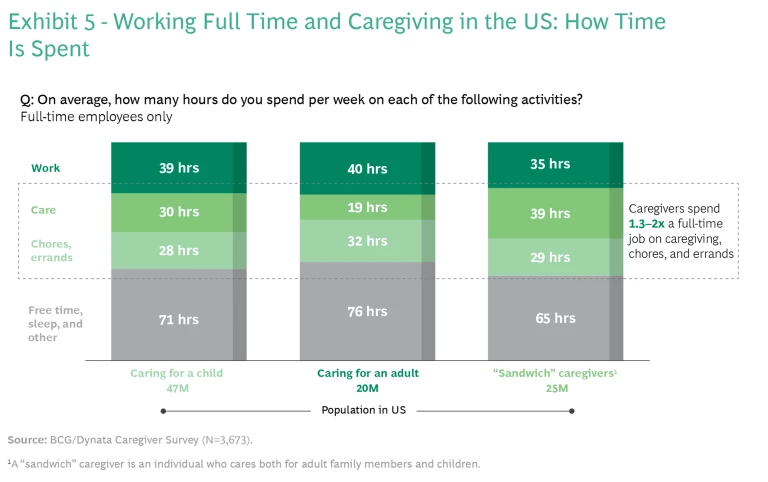

About 43% of employed caregivers, or about 40 million people, rely on paid-care support to go to work. These employed caregivers spend another 20 to 40 hours a week on their care responsibilities, based on our survey. Tack on another 30 hours on reported chores and errands, and caregiving is more than a second full-time job. (See Exhibit 5.) Worker shortages and rising costs strain the care system, forcing many families to make tradeoffs between paid work and caring for loved ones. They need cost- and time-saving support.

The expenditure offered incredible return in terms of loyalty and peace of mind for our current employees. It saved them commuting time, and they were close by if their child had an emergency. It was also a terrific recruiting tool. — Indra Nooyi, former CEO of PepsiCo, on spending $2 million to build a childcare center on the company’s corporate campus in Westchester, New York

Universal Childcare

To ensure access to quality, affordable childcare, policymakers must recognize the need for subsidized or universal programs. That’s happening slowly. In October, New York City passed legislation increasing accessibility for childcare services, including a pilot program providing grants to childcare centers at significant risk of closure, and a task force to focus on how to implement childcare for all. Oklahoma introduced a universal pre-K program for four-year olds in 1998, and pre-K enrollment rates in the state today are twice the national average. The W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research estimates that in Tulsa, Oklahoma, this program could generate a long-term benefit to the state of $9,000 per child, twice what the program costs.

The private sector also has a crucial role to play in supporting employees with care expenses through subsidies, as earlier mentioned, and through onsite and near-site childcare. The insurance company Aflac, based in Columbus, Georgia, provides both.

Paid Leave

The US is the only OECD country and one of six countries in the world without paid maternity leave. Despite being an economic leader, we are behind the rest of the world when it comes to offering relief to mothers, fathers, and caregivers more broadly.

Some US states have recognized the need for such policies, and those that have passed paid-leave laws are already seeing benefits. California, for example, was the first US state to implement paid family leave (PFL) to support caregivers. The state requires eight weeks of PFL to care for a sick or disabled loved one or a new child. While this leave policy is ten fewer weeks than the average paid maternity leave of OECD nations, it trumps the US federal policy of zero weeks. Since enactment of PFL in 2004, weekly work hours for mothers of one- to three-year-old children have increased by 10% in California in the years immediately following leave.

The private sector plays an important role in providing paid leave. According to the Society for Human Resource Management, about 35% of employers offer paid maternity leave, and about 27% offer paternity leave.

Workplace Flexibility

COVID-19 pushed many companies to adopt more flexible policies. Sustaining these new rules and habits are essential to the success of caregivers in the workforce. Flexibility both in terms of when people work and where they work is important. Corporations should continue to support flexible locations, including remote and hybrid work, to accommodate those with caregiving responsibilities and to save commute times. When Dell formalized a flexible hours and location policy in 2019, it saved the company $12 million annually due to reduced office-space requirements and improved its employee loyalty score by 20%.

The US used to be a leader when it came to progressive programs and equal access. We were the first country to offer free high school—other countries thought we were crazy but look where it got us. But now, we sit far behind many developed countries on federal care, leave, and paid-caregiver provisions. — Reshma Saujani

Innovation

Even though technology can’t replace the human touch needed to provide care, the broad scope and impact of paid- and unpaid-care roles mean vast opportunities for innovators. Caregivers are consumers with spending power, and today they have several unmet needs. Meeting these needs presents a huge market opportunity. According to The Holding Co., a design firm focused on the economics of care, more than 200 venture-backed care companies were founded between 2016 and 2020, and $3 billion was invested in care companies in 2021. In particular, our current system of caring for elders isn’t going to scale to meet the demand we’re facing, and we need innovation to tackle the looming eldercare challenges on the horizon.

Innovators have an opportunity to leverage technology and data to better enable paid-care workers and employed caregivers to deliver care, improve their job experience, and increase operational efficiency. Sensi.Ai, for example, is a virtual in-home care agent that provides immediate alerts for potential emergencies, enabling paid-care workers in care facilities to focus their time on elderly individuals most in need.

Technologies like these relieve a difficult aspect of caregiver work—constant, consistent, and intensive monitoring—making the job more efficient, more manageable, and more sustainable, as well as making the patient experience more pleasant. Ianacare, a platform that connects caregivers to employee benefits, local resources, and a community of caregivers, partners with employers and health plans to offer caregiver solutions in one place, helping them feel less alone and saving time while researching and purchasing care solutions. When the insurance company Anthem (now Elevance Health) partnered with Ianacare, employees reported an 83% increase in productivity and a 30% decrease in stress and burden.

The venture capital industry has been funneling billions of dollars of investment into software innovation narrowly focused on ‘known-market opportunities’ like enterprise efficiency (digital marketing, CRM, and database companies) or mobile gaming, or ‘more futuristic frontiers’ like space and crypto. Silicon Valley has largely ignored the massive market opportunity to digitize and advance the care economy. — Joanna Drake

Finally, companies like Papa address the paid-care worker shortages directly through creative solutioning and tapping into intergenerational pools of supply. Papa is an online marketplace where older adults and families can hire part-time workers as “Papa Pals” to assist them with nonmedical care, such as errands, chores, or even companionship. The platform is covered by insurance, is nationally accessible, and leverages helpers across generations to help solve the severe supply shortages we face in the care economy, thus allowing our elderly to age in place with dignity for longer.

The Time Is Now

Growth in the US is suffering because the care economy is inefficient and disorganized, and we face significant further economic and social risks if we don’t plan now to confront growing shortages in the years to come. With a looming $290 billion in annual economic loss, business leaders and policymakers can’t afford to ignore care economy dynamics any longer.

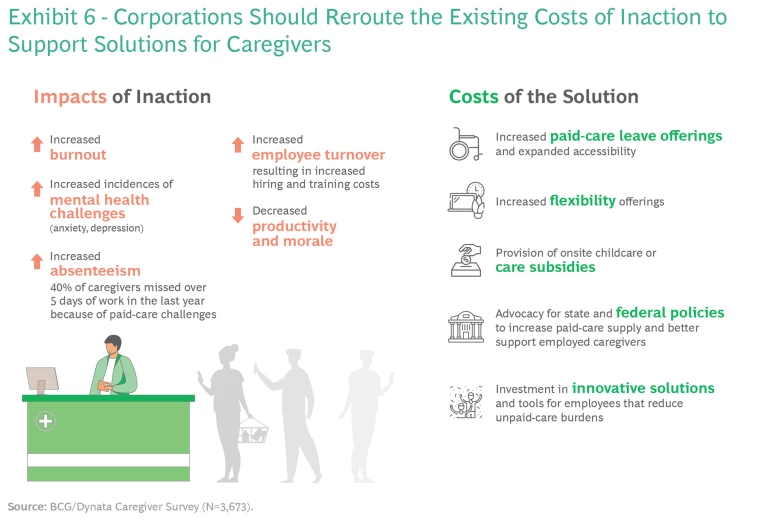

There is no single solution—building a resilient, lasting system requires input and action from all sectors. And, for CEOs, the cost of inaction is high. Not only are related issues affecting morale and productivity, but our BCG/Dynata survey found that more than 40% of employed caregivers have missed more than five days of work over the last year simply because their paid-care support has fallen through. Further, when employees end up quitting, corporations are forced to devote additional resources to replace them. According to the Society for Human Resource Management, turnover costs can range from six to nine months of the replaced employee’s salary.

Forward-thinking CEOs would be wise to reroute these expenses toward developing a more caregiver-centric workplace by revamping benefit and leave offerings, advocating for policy change, or providing caregivers with time-saving innovation. (See Exhibit 6.)

Fixing the US’s broken care economy means building a society that protects the health and dignity of our elderly, nurtures and educates our children, secures the well-being of our adults, and ensures the equity of our workplaces.

Methodology

To size the impact of paid-care shortages on the economy, we focused solely on the care roles that employed individuals rely on to go to work: preschool, elementary, middle, secondary, and special education teachers; home health and personal care aides; nursing assistants, orderlies, and psychiatric aides; childcare workers; counselors, social workers, and other community- and social-service specialists; and other teachers and instructors. We assume that if these jobs aren’t filled, workers elsewhere in the economy may need to leave the workforce to manage their caregiving responsibilities. We built a model with three scenarios that fluctuate based on two main parameters:

- Relative attractiveness of paid-care economy jobs: the speed at which the paid-care economy can fill jobs relative to the rest of the economy. These in-person jobs, with relatively low pay and flexibility, generally are less attractive than many other jobs. The more attractive they become, the lower the overall economic loss. Our model uses BLS hiring and openings data over the last ten years to estimate attractiveness of care jobs relative to all other jobs (measured as the relative hiring rate for care jobs vs. other jobs), and takes the maximum, average, and minimum rates over this time as assumptions in our low-, mid-, and high-case estimations respectively.

- Employed caregiver response: the share of employed caregivers who reduce hours or drop out of the workforce to assume unpaid-care responsibilities in the face of care shortages, according to the BCG/Dynata survey. Data was collected from more than 3,600 employed caregivers across the US. Sampling balanced results to the US census for statistically significant representative behavior among US employed caregivers (at the 95% confidence interval). The higher the number of employed caregivers who leave the workforce, the greater the economic losses. Our model uses the survey responses to a question asking employed caregivers who rely on paid care: “Do you feel you can afford to leave the workforce and stop working?” In the low scenario, we included half of those who said “Yes, without any major financial concerns” (~10%); in the middle scenario, we included all those who said “Yes, without any major financial concerns” (~20%); and in the high scenario, we also included those who said “Yes, with some financial concerns, but doable” (~40% total).

This care shortage represents the fundamental mismatch between care supply and demand, and can therefore be used to calculate the two effects of this mismatch:

- Lost wages from unfilled paid-care jobs. Unfilled care jobs mean unrealized income. If the US were to fill the jobs and solve the shortage, it would realize the economic gain represented by the wages of these formerly unfilled care jobs. This paid-care “potential wage” loss is our first contribution to total economic impact.

- Labor force participation GDP loss. Because employed caregivers depend on paid care to go to work, shortages in paid care have implications for those in the broader labor force. We calculate this second impact by multiplying our care shortage by the employed caregiver response (the percentage of caregivers who rely on paid care to go to work times the percentage who could leave the workforce if their paid care falls through) and total GDP. This labor force participation loss represents the rippling GDP losses associated with a reduced labor force: the direct wage loss from workers leaving their job, the indirect output from jobs that supported the now unfilled job, and the lost consumption due to reduced income. We intentionally used GDP rather than just wages in this calculation to capture the broader effects of reduced labor force participation.

The authors thank Indra Nooyi for inspiring this article and advising them along the way. They thank Rich Lesser, Myra Strober, Reshma Saujani, and Joanna Drake for their input and expertise on the subject. They thank their BCG colleagues Kelsey Murray, Matt Simon, Christian Leavitt, Paul Swartz, Dan Kahn, Sally Wan, and Ezinne Mong for their contributions to the research and analysis in this article. They thank Lisa Kassenaar for her writing assistance. They also thank the team at Dynata for their collaboration on the survey that made much of this work possible.