Consumers are in control, and company strategies are shifting as the market matures.

Is the streaming-video marketplace of the early 2020s beginning to resemble the linear-TV landscape of 40 years ago?

Back then, ad-supported television still reigned, while cable, satellite, and other video distributors offered consumers a rapidly expanding number of paid-TV channels, the most popular of which were often packaged into bundles to appeal to particular viewer segments. Now, with the rebundling of streaming services into larger packages and a resurgence of advertising-supported viewership, could we be returning to that earlier era of video?

Over the past five years, streaming has brought consumers even more choice and wider options for advertising-free subscription services that offer TV shows, movies, and other programming. Viewers effectively create their own virtual bundles by buying individual native streaming services, such as Netflix, Amazon Prime Video, and Hulu. Recently, we have started to see mini-packages of programming from affiliated cable networks, such as Turner and HBO (HBO Max), the nonsports Disney networks (Hulu and Disney+), CBS and Viacom (Paramount+), and NBC Universal (Peacock). Consumers no longer need to pay for content they don’t want.

Consumers no longer need to pay for content they don’t want.

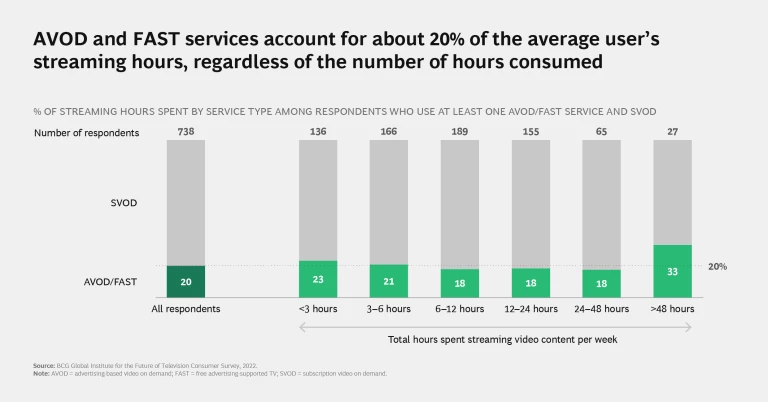

BCG’s latest research shows evidence that even as consumers continue to explore new services, they are becoming more selective in what they add long term—and more willing to subtract. They are spending an increasing amount of time with advertising-supported options (20% of streamers’ time is spent on ad-supported services) and creating their own bundles. As consumers become choosy and streaming services compete more intensely to retain existing subscribers and attract new viewers, including by offering ad-supported choices, streaming—now a huge part of the media industry —may indeed be heading back to the future.

Are We at Peak Paid TV?

The pandemic accelerated expansion of the streaming market, and even as COVID-19 receded, viewers continued to sign on. But since the advent of streaming more than a decade ago, a key question has been, how big is the addressable market? And in fact the market may finally be saturating. For years, market leader Netflix claimed that its total addressable market in the US was 60 million to 90 million subscribers. With the company now plateaued at about 75 million subscribers in the US and Canada (Netflix no longer breaks out US figures separately), this suggests the peak is at the low end of the range and calls into question the assumptions underlying many streaming services’ business models.

Two trends are at work. First, it has become harder (and more expensive) for streaming services to maintain the volume of high-quality content they need to stay distinctive. Second, consumers appear to have reached the limit of what they are willing to pay for ad-free TV, both at individual price points and in their total spending across services.

Some in the industry have anticipated this. While the two largest subscription-based providers, Netflix and Amazon Prime Video, have long been ad free, many other media companies have launched subscription services that include an advertising-supported tier (HBO Max, Peacock, Paramount+, and Discovery+, for example). Disney recently announced that it, too, would offer an ad-supported tier, and Netflix has now said it will investigate an ad-supported offering.

As it becomes clear that streaming is no longer a pure growth market, we can expect strategies to shift and the market to move into the next phase of maturity as competitors focus more on profitability and test a variety of approaches, including new business models and pricing plans, bundling, partnerships, and M&A.

The Consumer’s View

Here are some of the findings from the fourth annual consumer survey conducted earlier this year by

BCG’s Global Institute for the Future of Television

(GIFT). The nationwide US survey included a census-balanced sample of about 2,000 paying (or for free services, active) users of at least one subscription video on demand (SVOD, including tiers with ads) service; free advertising-supported TV (FAST) service, which includes advertising-based video on demand (AVOD); or virtual multichannel video-programming distributor (vMVPD) service. Here’s what we found:

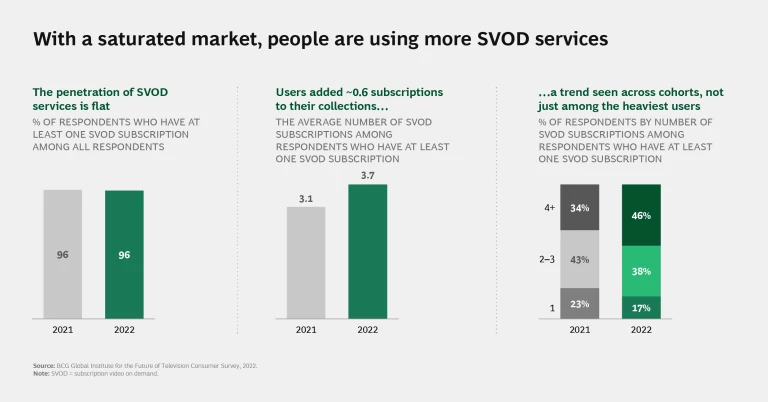

- People are using new SVOD services. Individual users added about 0.6 subscriptions each to their collections (since last year) as the number of available SVOD services continues to increase.

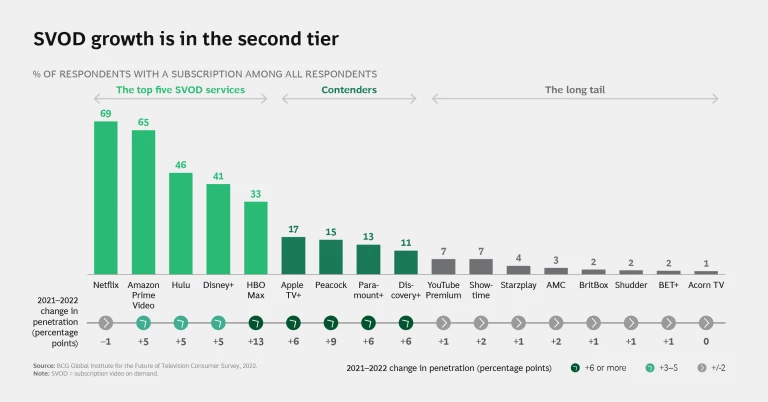

- But this growth is coming from the second tier. The four leading SVOD services (Netflix, Amazon Prime Video, Hulu, and Disney+) each added minimal or no share in 2021. Netflix was down 1%, and indeed the market leader reported that it lost subscribers in the first quarter of 2022, after the survey was completed. The growth of 0.6 subscriptions per person was driven almost entirely by the next tier of general-entertainment SVOD services (such as HBO Max, Apple TV+, Peacock, Paramount+, and Discovery+).

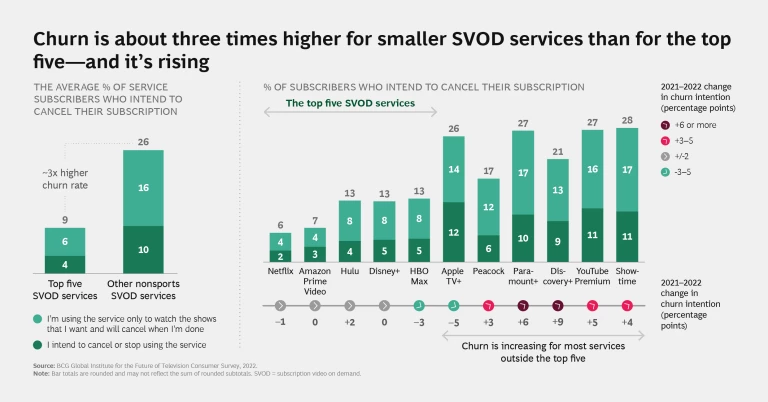

- The intention to churn is about three times higher for smaller SVOD services than for the largest SVOD services—and it rose for the smaller services year over year.

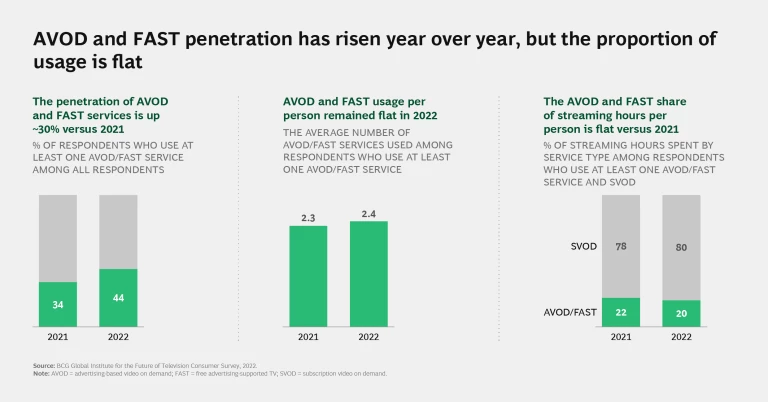

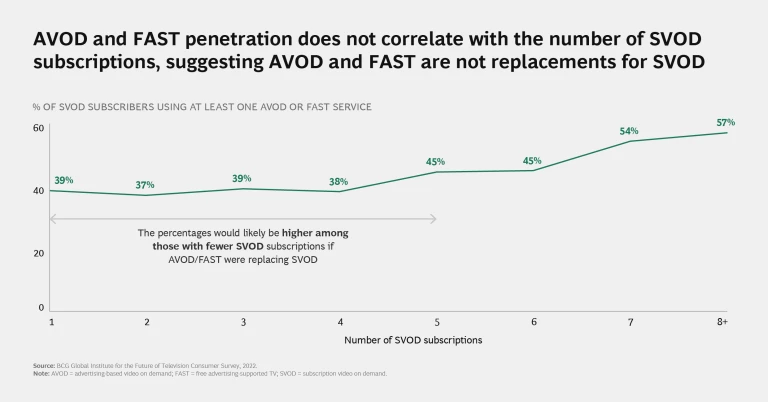

- The penetration of AVOD and FAST services increased for the second straight year. AVOD and FAST subscriptions jumped 10 percentage points year over year with almost 50% of streaming viewers now using at least one AVOD or FAST service.

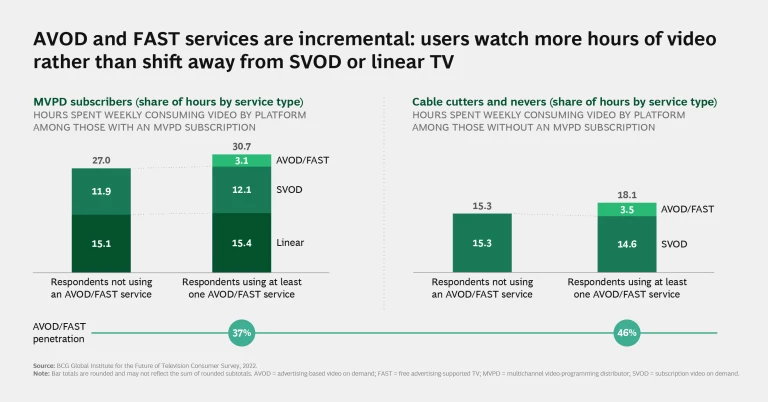

- The proportion of AVOD and FAST usage remains flat. These services account for a steady 20% of the average user’s streaming hours, which is unchanged since last year and is consistent regardless of how much total time a viewer spends streaming. AVOD and FAST services are also incremental—users of AVOD and FAST watch three more hours of video than nonusers, and all this time is spent with AVOD or FAST services. People do not shift time away from SVOD or linear sources.

- Openness to ads is high. Four out of five people see ad-supported content as high quality, and more than 60% of subscribers choose less expensive ad-supported tiers (when available).

Here’s a look at the data.

Consumers Control a Maturing Market

The data leads to several conclusions. First, the SVOD market is maturing and the total market size may be smaller than thought, as evidenced by rising churn, more than 90% of people saying there are enough or too many streaming services, and majorities of viewers choosing less expensive tiers to manage costs. Unencumbered growth for the largest streaming services appears to have peaked, and these providers will likely struggle to find new subscribers. The long tail of smaller streaming services will probably continue to grow, but these companies will likely struggle to gain or maintain scale as they fight among themselves for viewers who have a high propensity to churn.

Second, winning with a subscription-only strategy will be tough. As mentioned above, nearly all major streaming services have already rolled out (or are planning to roll out) cheaper, ad-supported tiers. And a lot of consumers are opting for less expensive plans over full-priced, ad-free alternatives. As competition for a limited pool of subscribers picks up, providers may be unable to push through price increases. Advertising may be one of the few tools that companies have to drive revenue.

Winning with a subscription-only strategy will be tough.

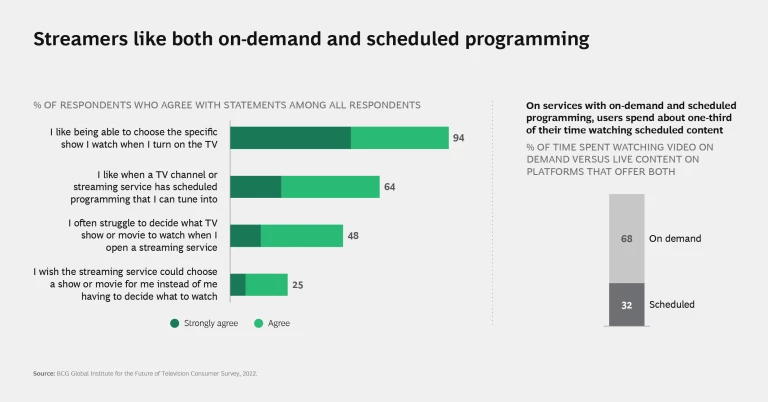

Third, AVOD is here to stay, which may alter the advertising landscape for TV permanently. Our expectation—posited last year—that AVOD services could gain traction appears to be playing out. The good news is that these services seem to address a different use case than SVOD and are therefore additive. That means the rise of AVOD may provide a valuable (or even necessary) tool for video companies, rather than a threat. As viewers add AVOD services to their mix, they are using them for purposes other than watching a particular show. For example, subscribers to Peacock’s paid service are 1.6 times more likely to use the service to view a specific show than users of the free, ad-supported Peacock service (45% versus 29%). The bad news for those with both linear networks and streaming services is that the rise in advertising on streaming may ultimately take more dollars out of linear TV and further change how marketing budgets are allocated.

What’s clear is that consumers are in control. Streaming has greatly increased choice, and consumers are being much more selective about which services they adopt. Some of the assumptions underlying streaming business models may need to be revisited, and the ways in which all video companies compete will likely change as a result. We expect strategies to shift as competitors reevaluate their cost structures, focus on retention, and try out a variety of go-to-market approaches, including new tiers and pricing plans, bundling, and partnerships. Some may also entertain consolidation.