The transformation agenda for health care is government led, tailored to your country’s capabilities, and focused on better outcomes. Use this domains-and-roles framework to set your health care systems on track.

The digital transformation of health care has gained momentum since the pandemic began. As COVID-19 spread through the world, many health care systems introduced measures like vaccine passports, QR code-based identification, virtual care and telehealth services, predictive analytics systems, and governance structures for sharing data and back office digital resources. In one recent BCG survey, health care leaders said that advances in technology, propelled by the crisis, helped them overcome decades of inertia in their organizations.

These achievements are impressive in many ways, but they are not enough. First, they do not deliver on the primary goal of health care systems around the world: fundamental improvement in patient outcomes.

Second, they are not comprehensive enough to be prepared for the health care challenges to come. Despite improvements made to manage the pandemic response, many health care systems still have fragmented IT infrastructure, incompatible standards, and narrow activities that only apply to specific organizations. Digital health care transformation initiatives still tend to be oriented toward the technology itself, rather than better patient outcomes or the system’s capacity to deliver them.

As the pandemic moves into its next phase, health care ministries and agencies should be thinking about creating more comprehensive digital platforms and systems to provide the improved, patient-centric health care that people deserve. They have an opportunity to maximize the benefits of the technology—not just cutting costs but bringing disparate parts of the system together, improving long-standing practices that restrain health care quality, and achieving their patient-centric goals.

Defining Digital Health Care Transformation

The digital transformation of a health care system can be defined as shifting the system’s ability to create value through its use of advanced technology. In the context of health care, value is the achievement of desired outcomes, including those that matter to patients, at the optimal cost. A variety of skills, experience, and managerial structures come into play with technology to accomplish this, and these capabilities tend to increase over time as organizations put them into practice.

A digitally mature health care industry could unlock enormous value and achieve great gains in quality of care.

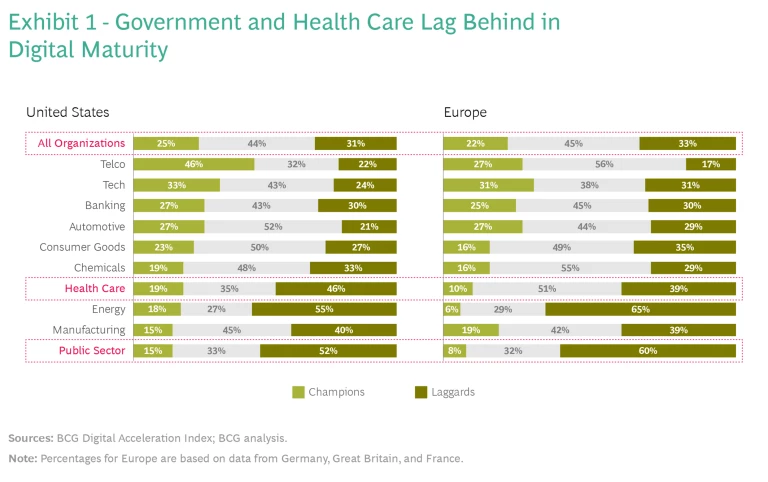

The digital maturity of health care and public sector organizations, as shown in Exhibit 1, tends to lag behind other sectors . This finding comes from BCG’s Digital Acceleration Index , based on annual surveys of senior executives at 11,000 companies. The lower relative scores show how challenging the task is for health care and government, but also how compelling the opportunity. If the health care industry can catch up with its counterparts in, say, consumer products or finance, then it could unlock enormous amounts of value and achieve great gains in quality of care and patient safety.

The scale and fragmentation of the health care system suggest that the responsibility for its digital transformation must lie with government. Government agencies can operate at a nationwide scale. Their activities can align with all requisite agencies, businesses, practices, professions, and patients—without concerns about competition. Government oversight is also needed to protect the vulnerable and ensure that innovations and benefits are spread broadly across the population. In short, only governments have the scope and perspective to foster comprehensive change.

But many governments have not stepped up to this role. Consequently, they have had difficulty in realizing value from their investments in the digital transformation of health care—including investments in IT, digital infrastructure, national e-health solutions, and artificial intelligence (AI) . Even highly centralized systems with single-payer funding have struggled. When the new ways of working don’t integrate into and support the patient-centered practice of physicians, nurses, and staff, the total impact is less than expected, and much of the investment may be lost.

Drawing on our extensive experience around the world, we have identified a framework that can help governments succeed in digital health care transformation. The framework identifies four domains of activity and five possible roles for action in each domain. It provides a foundation upon which to realize the full potential of today’s health care systems.

Making Transformation Manageable

Because of its clear value to all aspects of society, improving the health care sector is a perennial goal. And as an exceptionally complex and expensive sector, with an ever-evolving body of clinical knowledge and practice, there are always multiple interests and perspectives to navigate. To transform digital health care, the system must first be divided into broad but manageable domains of activity—transcending organizational boundaries but allowing for focused changes. Based on BCG’s experience with clients, these four domains represent what we think should be the highest priorities:

- Building Digital Health Care Infrastructure. The underlying technological framework that enables the sharing of services, pooling and sharing of data, and development of compelling online resources for patients, employees, and other stakeholders.

- Unlocking Bionic Care Delivery. The provision of services and tests through combined face-to-face and virtual experience (the word “bionic” refers to the blending of human and technological capabilities).

- Harnessing Data Analytics and AI. Gathering data from the field and using it to tighten the loop from insight to action: personalizing care, expanding knowledge, reducing unwarranted variation, and reducing poor clinical practices.

- Digitizing the Department. Transforming governmental practices to make the most of digital capabilities in health care research, management, and funding.

A comprehensive digital health care transformation initiative would cover all four of these domains. However, in any given country, there is a different mix of priorities. Some domains may already have a high level of digital maturity. Others may need urgent attention.

Five organizational roles can foster digital maturity in health care: Champions, Convenors, Sponsors, Regulators, and Service Providers.

For those who are setting the course of activity in a given country—typically senior executives and policy makers in health care ministries and agencies – the decision-making sequence is clear. It starts with an assessment of these four domains, in light of the overall goal of patient outcomes, and the immediate priorities for the country.

Consider your overall challenges and goals. Where does the system need to improve? Monitoring disease vectors? Care delivery? What types of outcomes do you want the system to achieve? Finally, which of these four domains can best address your goals?

What Roles Could You Play?

Having identified areas to focus on, the next step is to clarify how your agency will foster digital maturity in the domains you have chosen. Ministries and agencies can play a wide variety of possible roles, each calling for different capabilities and activities. Drawing on BCG’s experience and observation, we categorize these possible roles into five broad archetypes:

- Champions lead the digital agenda from the front. They put forth an executive mandate—a form of strong leadership which all stakeholders follow. They develop national or regional strategies to achieve this mandate, developing their own digital platforms and talent.

- Convenors establish national frameworks and collective goals through public-private ecosystems . They support broad partnerships among multiple businesses and industry groups, and embrace market-based solutions in which private enterprises play leadership roles and serve public health priorities.

- Sponsors focus on investments, grants, and incentives to industry partners who in turn provide services for the public. They find the right “guardrails”—funding, reimbursement, penalties, tax policies, and incentives—that will foster the behavior change needed for digital transformation.

- Regulators define and enforce standards for health care effectiveness and quality, including digital capabilities. They limit their involvement to overseeing aspects of digital activity, such as data interoperability, patient privacy, cybersecurity, and professional conduct. They are typically uninvolved in providing services or procuring technology.

- Service Providers are directly involved in delivering tech services to health care providers, which may include everything from infrastructure and platforms to virtual care technologies. They increasingly operate as digital natives, adapting new ways of working and harnessing internal operational efficiencies.

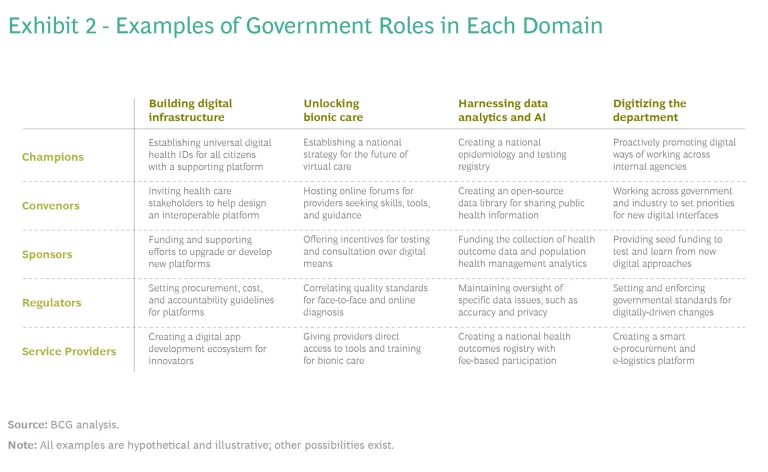

Exhibit 2 shows a matrix of domain–role combinations. Each cell provides an example of how a role might play out in a particular domain.

To adapt this framework, select a role for each domain to be addressed in your digital health care transformation initiative. By identifying distinct roles for each domain where you’re active—and pinpointing goals for each—you can better focus your efforts and use limited resources most effectively.

You don’t have to play the same role in each domain. The same government can act as a Regulator of virtual care (unlocking bionic care delivery), as a Service Provider of electronic health records (building digital infrastructure), and as a Champion of agile innovation processes (digitizing the department). Aim for a combination of roles that will lead to success.

Maintain flexibility. As the digital transformation of your health care system proceeds, you might shift —for example, from being a Convenor of digital infrastructure in its early years, to a Regulator setting standards, to a Service Provider or Champion. The role might also shift to reflect market disruptions, new technologies, emerging challenges, and new priorities of the health care system strategy.

Finally, determine how you want to implement the goals and your current capabilities for delivery. This will give you a sense of the gaps that need to be filled—either internally or externally—to achieve the goals.

In the next four sections, we discuss how these archetypal roles might apply to each domain and provide examples of best practices, based on BCG’s work and observations of this emerging field.

Building Digital Health Care Infrastructure

In this domain, you build, consolidate, and upgrade information and communications systems so that all relevant health care entities, inside and outside government, connect through shared standards. In many cases, this will require sizeable investment and coordination, replacing incompatible legacy systems along the way.

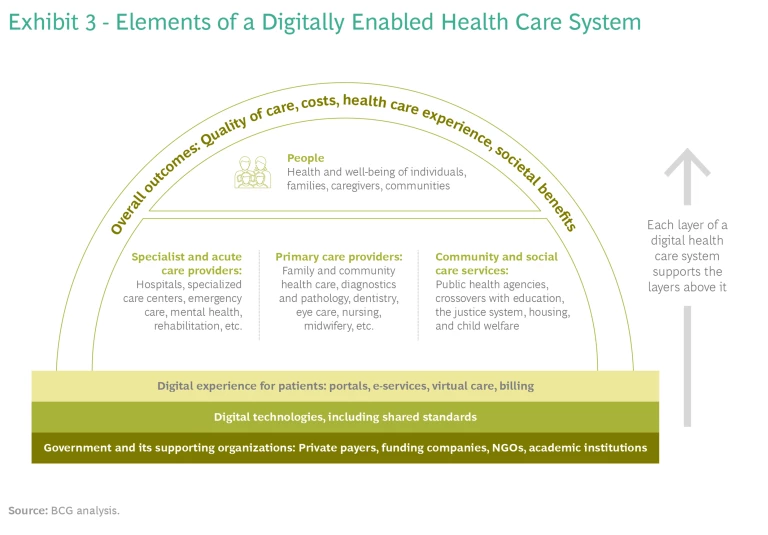

Exhibit 3 shows the wide landscape that can be connected through a digital health care system. There may be hundreds of entities involved. Some may lie outside the strict boundaries of the sector; for example, health care ID cards could be linked to tax, welfare, and transportation agencies. All groups can be connected through an automated programming interface (API) infrastructure, with common data sharing and interoperability standards.

The infrastructure should continually expand to support a variety of added services, such as electronic health records, e-referrals, and digital tools for self-care. Make it a priority to protect privacy and safeguard against cyberattack.

Governments approach infrastructure design based on the role they have chosen. In the UK, the National Health Service takes the role of Champion. Its extensive digital health infrastructure includes a DigiTrials platform, supporting clinical trials of new medications at scale. It also provides a national API platform that makes it easier for the broader eHealth community to link data.

The Estonian government is a Service Provider. The country’s national electronic health records system, called X-Roads, receives data in real time from primary care facilities, hospitals, registries, pharmacies, and school health services. Data is protected by KSI blockchain and e-ID security layers. X-Roads delivers 99% of the country’s prescriptions digitally.

Unlocking Bionic Care Delivery

In this domain, you support telemedicine and other forms of digital health care delivery. Face-to-face contact will remain when patients want or need it, but many routine consultations will take place through laptops and smartphones. BCG estimates that at least $1.6 trillion can be saved globally each year through digital services. One service, which used telemonitoring for patients released from hospitals, generated a 44% reduction in readmissions within 30 days.

BCG estimates that at least $1.6 trillion can be saved globally each year through digital health care delivery.

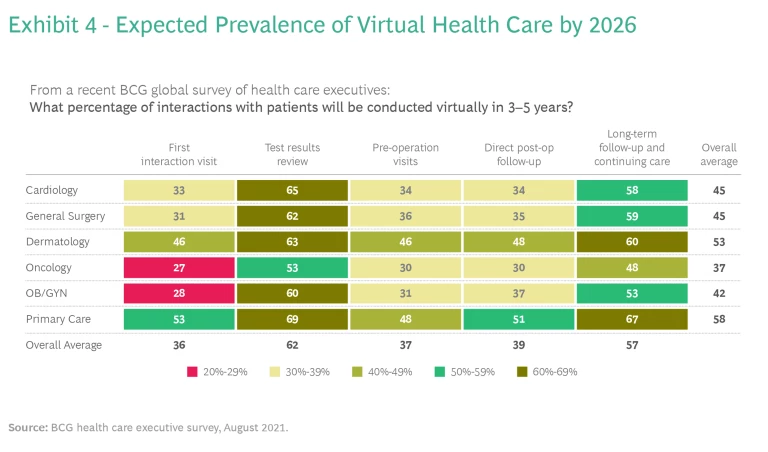

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), in reviewing studies of virtual care, concluded that telemedicine consistently enables improved coordination, more streamlined management, and reduced fraud and overclaiming. Perhaps that’s why the public appetite for this service continues to grow. Exhibit 4 shows expected growth through 2026, when close to half of all health care interactions are expected to take place virtually.

The optimal government role in this domain depends in part on whether the system delivers services directly or reimburses providers. Germany acted as a Champion in 2021 when it began to fast-track digital apps for reimbursement. France and Belgium adopted a similar approach soon afterward. The Canadian province of Alberta took on a Regulator role, introducing standards for virtual care and limiting it to physicians registered there.

No matter which role you take, some action steps are important in this domain. Reorient funding toward digital care, especially when it helps patients stay home and avoid long hospital stays. Ensure comparable access for people who do not have regular access to computers. Legislation should not automatically favor either in-person or online care; it should enable clinicians and patients to choose the best medium on a case-by-case basis.

Harnessing Data Analytics and AI

In a well-organized health system, data is gathered and analyzed regularly at a national scale—for example, to monitor the spread of disease and the efficacy of treatment. Data and analytics have had extraordinary impact on the quality and cost of care. One such project, used to assess patients who had a stroke and provide preliminary treatment, reduced the time of diagnosis by 96%. Another achieved a 50% reduction in complication rates.

To take full advantage of advanced analytics techniques, such as AI and machine learning, you may need linked digital platforms with data capture and storage, APIs to allow safe access to data, algorithms for continuous machine learning, and mechanisms for security, resilience, and redundancy. Make the results of analysis available through real time online dashboards. They alert physicians and other staff members to changes in a patient’s condition, and thus help them make more timely decisions.

When gathering data, cover the entire patient journey, including community-based care, acute care, and social and behavioral factors. Establish and maintain high standards for integrity and ethics. Foster transparency and responsible AI , so that there is always human oversight of the way the data is gathered and used. For example, to ensure that analytics avoid ethnic or gender bias, the scope of patient data used to train the algorithms must be large and varied enough to include people from all relevant backgrounds.

The government of Austria has pioneered the use of data in a Service Provider role. During the pandemic, the Austrian health ministry used a quantitative algorithm it had developed to create a platform of shared COVID-19 information. Public health officials and other professionals used it to receive warnings, coordinate lockdowns, and develop strategies for reopening their businesses.

By contrast, Japan acts as a Regulator, requiring all companies using AI in health care to publish an analytics usage policy and notify the public of their data-related practices. Singapore is a Convener. Its platform allows tech developers and experimenters to work with COVID-19 data, without exposing the wider population or health system to development or security risks. This approach enables the government to continue its rapid pace of digital innovation while monitoring the impact on patient privacy and safety.

Digitizing the Department

Every health agency has a back office that must be digitized to operate effectively. By adopting a bionic organizational strategy—combining technological capability and human creativity—governments can consistently deliver better outcomes. This transition requires investment in workforce skill-building as well as in technology, but these costs are typically recouped very quickly.

Many of the changes involve new managerial practices. Digital technologies can spark more creative ways of working and bring people together across organizational boundaries. Agile, multidisciplinary teams assemble to solve problems—focusing on outcomes and business value, experimenting with new products and services, and redesigning processes for productivity and better output. Technology—software and hardware—should be modular and adaptable, so it can be refined and updated easily. It is designed with APIs and microservices, enabling rapid reconfiguration without overhauling the entire underlying system.

In the UK, the NHSX agency (the X stands for “user experience”) played a Convenor role. It brought together key stakeholder groups who were intent on digitizing their management systems. These stakeholders included clinical commissioning groups and those advocating for sustainability and transformation. In 2021, NHSX released the “What Good Looks Like” framework, drawing on the lessons and best practices of NHS trusts.

The US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) took the role of a Service Provider in adopting a new IT and data platform to digitize internal operations during the COVID-19 pandemic. HHS used this platform to coordinate the vaccine distribution supply chain and all government-sponsored vaccine dosage programs. The platform has more than 2,000 users representing a variety of organizations, including federal agencies involved in pandemic response; public health organizations from most states and territories; local governments that receive vaccines; and commercial users, including all retail pharmacies.

In Australia, the government of New South Wales took a Champion role. It set up a system-wide Critical Intelligence Unit to combat COVID-19. This drew together data feeds for system performance and capacity, epidemiological trends, and clinical intelligence, providing support for agile decision-making to manage the pandemic.

The Future of the Health Care System

Digitally transforming a health care system is a complex undertaking, involving many moving parts. But it need not be daunting. As we’ve seen, by identifying domains and roles that reflect your organization and goals, you can keep the task manageable and build your capacity to keep expanding. These practices will help you make continual progress on the journey.

Given the human stakes, the health care sector should be a leader in digital maturity.

Be comprehensive. Articulate a vision for the whole digital transformation , even though you may not expect to implement all of it at once. Don’t just focus on government services (such as claims). Consult with relevant stakeholders in business, academia, and not-for-profits to better understand what aspects of digitization would make a difference for them, and which aspects are most urgent.

Emphasize the overall patient experience. Individual patients are typically the only people to experience the system as a whole. They are increasingly interested in being actively engaged in their health care, and in setting their own priorities. Take their concerns and interests into account—for instance, get a sense of what it’s like for patients to navigate through all the different groups in your health care system.

Harmonize the technology. Reduce hurdles such as barriers to data sharing. Design common user interfaces so that a site for ordering prescriptions seems familiar to those who have already booked appointments. Build in escalating protocols for patient communications, so that warnings and nudges don’t go unnoticed. Identify care gaps—for example, monitoring high-risk medication or helping manage cognitive decline—where digital innovation can make a difference.

Set milestones that reflect whole-system progress, not just individual programs or projects. Keep the plan flexible; refine it iteratively as you make progress, as the needs of your health care system evolve (or become apparent), and as new technologies emerge. Identify the skills needed for each milestone, including digital skills. When developing funding estimates, keep in mind the need to address the ever-growing range of cybersecurity threats.

Use the framework of domains and roles to set limits and priorities. You can’t do everything at once. For each stage of the plan, pick the combination of domain and role that is most likely to work. If the plan includes data and analytics, for example, are you better equipped to provide services directly from the government? Or to be a sponsor, offering funding and guidelines? Or to champion a broad new analytic platform?

Make room for other organizations. When the government chooses a role for itself, it limits what other actors in the system might do. For instance, investors might be willing to sponsor some initiatives as for-profit ventures, without requiring direct government involvement—but they will shrink back if the government takes a sponsor role.

Upgrade technology only after you understand the human factors. Stay on top of trends: software, hardware, and life sciences innovation will all continue to advance. Design your architecture to be modular, upgradeable, and adaptable. Build applications and solutions that can easily scale after the pilot phase has proved them out.

Optimize human resources. Pay close attention to recruiting and skill-building across the new health care system you are developing. It is a challenge to attract, train, and retain talent today, especially in the public sector.

The public has grown to expect a high level of digital maturity in its institutions, and they will expect even more from health care in the next few years. Health care doesn’t have to lag behind other sectors. In fact, given the human stakes, it should be a leader. Governments must therefore seize the opportunity to realize the full benefits and value of a digital health care system. By fully embracing digital technology in this way, tailored to the needs of your citizens and community, you are building the 21st century health care system that people deserve.