Millions of small, independent shops are the cornerstones of African commerce. Now they’re diversifying, digitizing, and partnering with modern retailers to reach the next level.

Stefano Niavas

This is a modal window.

Stefano Niavas

In Morocco, it’s known as a hanout. In Egypt, it’s a bakkal. In Kenya, it’s a duka. In South Africa, it’s a spaza. In the Yoruba language of Southwest Nigeria, it’s an oja. By whatever name, the traditional retailer is the cornerstone of socioeconomic systems across Africa. Despite the advance of supermarkets, convenience stores, and other modern formats, African consumers on average continue to buy more than 70% of their food, beverages, and personal care products from the continent’s more than 2.5 million small, independent shops.

Yet traditional retail in Africa faces many imposing challenges, including the expansion of modern retail, the nascent rise of e-commerce, and changes in consumer behavior that were accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic. So, what does the future hold? For answers, we studied more than 4,500 small retailers in five of the biggest African markets: Egypt, Kenya, Morocco, Nigeria, and South Africa.

We concluded that the traditional retail sector will remain at the core of African commerce in all but a handful of nations, such as South Africa, for the foreseeable future. But there is strong momentum for change in the traditional retail experience.

Challenges for traditional retail in Africa include the expansion of modern retail, the rise of e-commerce, and pandemic-related changes in consumer behavior.

Our research revealed several factors driving this transformation. One is the profile of African shop proprietors, who are typically more educated and digitally savvy than the general population. Another is that small retailers are willing to modernize their businesses in response to a challenging, shifting landscape. Finally, a growing digital ecosystem in Africa is enabling small retailers to offer new online solutions for payments, procurement, and last-mile delivery.

This evolution will take different shapes across Africa—and will depend on each nation’s level of digital maturity and economic development. The strategies of modern retailers, such as supermarket and convenience-store chains, and solutions provided by tech companies will also influence the future of traditional retail. The opportunities for various players in the retail ecosystem, therefore, will vary country by country. Still, we expect that traditional shops will account for 65% to 75% of sales in most of the region through at least 2030. The expansion of e-commerce and payment services, moreover, might provide small retailers with a new role in digitized trade and payments.

Why Traditional Shops Still Dominate

Traditional shops not only dominate retail in all but a handful of African markets—their share is high even when considering African nations’ level of development. Globally, there is a strong correlation between per capita GDP and the market penetration of modern retail. In many African nations, including Morocco, Egypt, and Nigeria, the reach of modern retail is well below its potential. (See Exhibit 1.)

Several factors make traditional retailers remarkably resilient. Small shops offer the proximity, flexibility, and convenient operating hours needed to serve their communities. They also often allow customers with limited incomes to purchase small quantities on credit.

By comparison, many modern retailers in most of Africa have failed to devise a winning model that can be scaled up to address the needs of most customers. Their locations and value propositions primarily cater to upper-class consumers. And while modern retailers in Africa are embracing e-commerce , particularly since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, they are not doing so as quickly as in Southeast Asia and Latin America.

Five African Markets, Five Retail Landscapes

Africa’s retail landscape is far from monolithic. It is evolving at different speeds across the continent. The five markets in our study illustrate these differences.

In Nigeria, the more than 600,000 small retailers account for 97% of national sales. Traditional retail essentially consists of small kiosks and open-air markets. Modern retail remains very fragmented and is led by international hypermarket brands, such as Shoprite and Spar, and a few small local chains, such as Hubmart, Justrite, Addide, and Foodco. Modern chains are struggling to expand due to currency devaluation, underdeveloped and inefficient transportation infrastructure, poor logistics capabilities, inadequate electrical power, and other complex challenges.

Traditional retailers still account for 82% of sales in Morocco. They also play an important economic role, since 90% of them offer credit. This partially explains their resilience despite the expansion of modern retailers such as Marjane, Carrefour, and BIM. We estimate that the most affluent 15% of Moroccans account for around 65% of modern retail sector sales. To expand further, modern retailers will need to find the right formats that address middle- and lower middle-class consumers.

In Egypt, more than 120,000 small grocers and kiosks account for 75% of retail sales. But modern retailers, particularly locally based ones, are emerging rapidly across all formats. Modern formats posted 21% annual growth from 2015 through 2020. Their market share over that period rose from 15% to 25%, one of the highest growth rates across the continent. The Kazyon discount supermarket has expanded rapidly in Egypt since 2014, with small-format stores in underserved low- and middle-income areas. Other successful Egyptian supermarket chains include Awlad Ragab and Seoudi.

Consumers in Kenya buy 77% of their goods from more than 250,000 small stores. Kenya has several well-established hypermarket and supermarket chains. Modern sector growth has been sluggish in the past few years, however. Several players have exited or gone bankrupt through a combination of poor management, overly rapid expansion, and inappropriate formats. The nation’s dynamic digital technology ecosystem and the significant penetration of mobile money are stimulating a transformation of both traditional and modern stores.

South Africa is an exception on the continent. Its modern retail sector is quite mature, with less room to grow. Supermarket chains such as Shoprite, Pick ‘n’ Pay, and Spar account for more than 70% of retail sales, although traditional shops retain a very strong presence in townships.

Despite their differences, in each market there is momentum toward the modernization of small retailers. Several factors account for this: the profile of the retailers, their willingness to diversify their businesses in response to a challenging environment, the growing availability of digital solutions from technology start-ups, and supportive government policies.

Young, Digitally Engaged Proprietors Driving Change

Until now, there has been little data on the owners of traditional shops. We conducted our survey to gain a better understanding of who they are, their needs, where they are located, how they operate, the major trends affecting them, and how they envision their future.

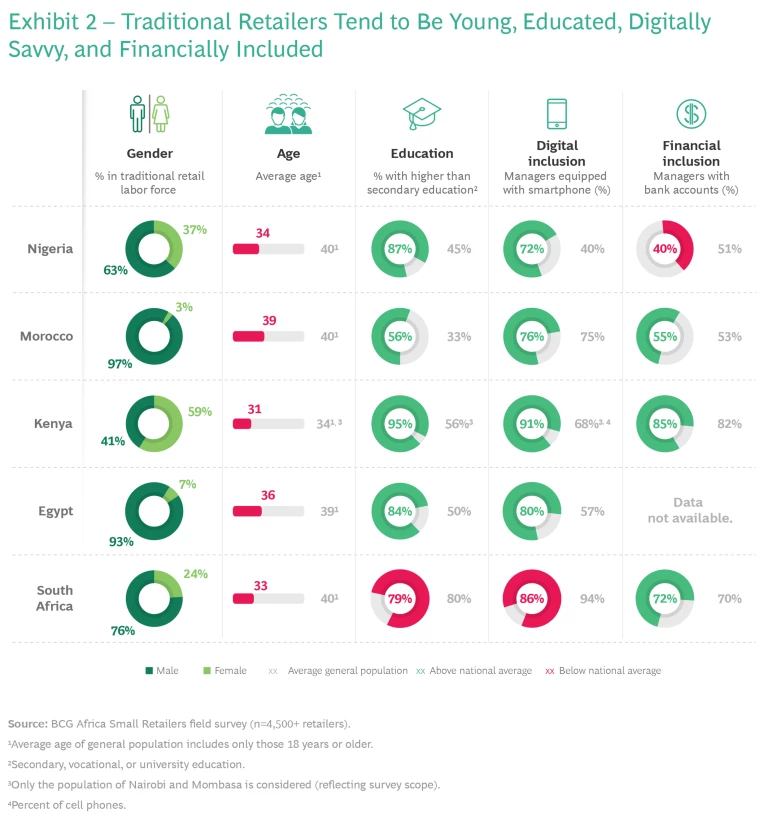

The proprietors of traditional African retailers are generally young and educated. Their average age runs from 31 years in Egypt to 39 in Morocco. In the nations we studied, an average of more than 70% of traditional retailers had high school, vocational, or university education—a level that is higher than that of the general population.

More importantly, the digital maturity of shop proprietors is also substantially higher than the national average. In Kenya, for example, 91% of proprietors we surveyed in Nairobi and Mombasa are equipped with smartphones, compared with 68% of the general population in those cities. The level of financial inclusion varies widely across the region, however, and is generally in line with the general population. While 85% of Kenyan shop managers have a bank account, only 40% of their counterparts in Nigeria have one. (See Exhibit 2.)

Eagerness to Modernize in Response to Challenges

We also found that the level of optimism among traditional African retailers is mixed. Seventy-nine percent of Kenyan retailers and 88% of Nigerians reported that they believe their business will grow in the years ahead, for example. But only 43% of traditional Egyptian retailers and 32% of Moroccans expressed optimism, perhaps because of the growth of small modern formats in their countries.

This market segment faces a number of challenges. The portion of retailers who said their business was hurt by the COVID-19 pandemic ranged from 19% in Nigeria to 43% in South Africa. High numbers of African retailers also reported that they feel under pressure from modern retailers.

In response to such challenges, traditional shops are diversifying well beyond daily essentials, such as fresh and packaged foods and home cleaning and personal hygiene products. Many small retailers now sell telecom products, such as prepaid cards and SIM cards.

In Egypt, for example, 69% of traditional outlets said they sell such products. A growing portion also offer digital services—and around one-third offer remote ordering and delivery and bill payment services. In Kenya, 97% of the small retailers we surveyed said they accept mobile money. Digital adoption is lowest in Morocco, where only 1% percent of respondents use mobile money and 29% use other digital services.

Digital marketplaces for inventory, e-payment services, and other tech solutions are transforming traditional retail across Africa.

The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated adoption of digital retail services in several markets. In Kenya, for example, the portion of retailers offering remote ordering rose from 27% in early 2019 to 39% in late 2021.

Start-Ups are Offering New Digital Solutions

A growing number of new technology providers in Africa are providing the region’s traditional retailers with innovative digital solutions that can resolve bottlenecks and accelerate their transformation.

Several digital technology providers are addressing inefficient distribution systems that often force retailers to close their shops for several hours so they can go purchase goods from wholesalers. This often makes it hard to obtain sufficient inventory. The Nigerian B2B digital marketplace Alerzo, for example, enables more than 100,000 users—90% of whom are women—to purchase inventory directly from manufacturers, receive and make cashless payments, and better track their revenues. Alerzo also facilitates a portfolio of digital services, including airtime purchases, bill payments, and peer-to-peer transfers. Some 50,000 African retailers use the Kenyan procurement marketplace Wasoko (formerly Sokowatch) to order stock on credit via a mobile app and receive it the same day. The Moroccan procurement B2B marketplace Chari, which has a market value of more than $100 million, aggregates demand from independent retailers through its app and delivers goods around the clock.

To thrive, traditional retailers must modernize by offering new services and leveraging digital solutions.

E-payment companies are also helping traditional retailers expand their digital capabilities. Egypt’s Fawry, an e-payment platform that has been adopted by around 30 million Egyptians and had a successful IPO, is a good example. Through Fawry’s platform, final customers can pay utility and other bills with cash by using terminals located in more than 225,000 service points (including retail stores), rather than by visiting the offices of agencies. In South Africa, the start-up Flash provides a similar service, making it the nation’s largest network for informal retailers.

In the long run, such platforms aim to provide super apps with a large selection of services. This would enable them to totally digitize traditional retailers and integrate them into the formal economy. Start-ups are also providing working capital and financial management systems to help traditional retailers grow and run their businesses more efficiently; however, they must overcome a lack of awareness and training among retailers.

Projecting Africa’s Retail Future

The future of retail in Africa can best be described as local and increasingly modern. By local, we mean that successful formats—whether big or small—will be tailored to the needs of their communities and that growth will be driven to a large degree by domestic ecosystems of entrepreneurs, investors, and innovators. By increasingly modern, we mean that traditional retailers will adopt more sophisticated business models and, in many cases, collaborate with chains operating modern formats.

Traditional retailers will continue to dominate. But to thrive, they must modernize by offering new services and leveraging opportunities offered by digital solutions. Many small retailers are already aware of this imperative and say they intend to take action in three ways. Our research found that a significant number of respondents, ranging from 48% in South Africa to 79% in Nigeria, prioritize offering higher quality products. A large majority in most countries would like to open more stores. And anywhere from 36% in Egypt to 59% in Nigeria cited “modernizing look and feel” as a priority.

In most countries, independent retailers can grow by becoming part of the network of modern retailers. Based our analysis, around 40% of traditional retailers in Morocco and Kenya are interested in affiliation or franchise models; around 50% of Egyptian and 60% of South African retailers are also interested.

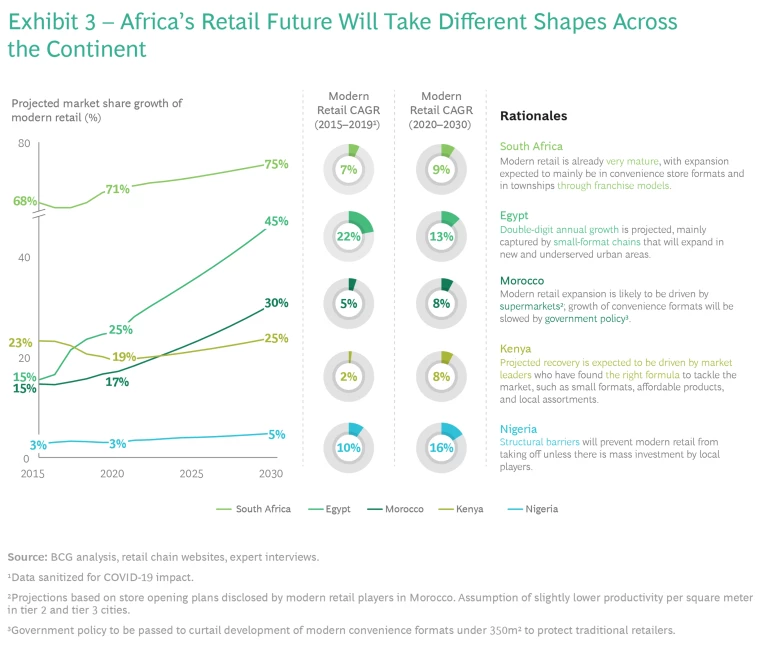

This future will take different shapes across the continent in accordance with local conditions. Our 2030 projections for the markets in this study illustrate this variety of paths. (See Exhibit 3.)

- In Nigeria, traditional retailers will dominate for the rest of the decade, but there will likely be relatively few changes in their product offerings and services. Based on current trends, the modern retail sector is likely to remain small, and still may not account for more than 5% of retail sales by 2030. Due to structural problems in Nigeria mentioned earlier, foreign investors are likely to remain hesitant about entering the market. Unless there is massive investment by local companies and progress in removing structural barriers, the development of modern formats will remain significantly below their potential.

- Morocco will remain a stronghold of traditional shops, more of which will likely adopt digital sourcing and payment. We expect modern retail to pick up, led by supermarkets and proximity formats (with or without franchise models), provided they find the recipe to develop profitable models to address lower-income households. We believe the modern sector’s market penetration could potentially approach 30% by 2030.

- Egypt will likely experience the fastest growth in modern retail. If growth continues along current trends, we believe that this segment has the potential to surge by around 13% annually and account for around 45% of sales by 2030. Local small format chains such as Kazyon and Awlad Ragab could capture much of the growth in underserved areas. We believe hypermarkets will sprout up in more cities, while convenience stores owned by local entrepreneurs will blossom in Cairo and Alexandria. Traditional retailers, meanwhile, will continue to grow at a slower pace. The most successful ones could potentially achieve greater scale by leveraging local digital start-ups and by becoming franchises.

- In Kenya, we expect modern retailing to resume growth. Under current conditions, its market penetration could reach around 25% by the end of the decade, led by current market leaders such as Naivas, Quickmart, and Carrefour that have managed to find the right formulas in terms of format and assortment to address the market. We expect local modern chains to try to expand with small supermarkets and convenience stores and by franchising. Traditional retailers will remain resilient in low- to middle-income areas and will likely diversify by adding more services and leveraging digital platforms.

- South Africa’s modern retailers will continue their steady growth if current trends continue, most likely by filling in the few remaining gaps in the market and expanding the spaza format in townships. The market penetration of modern retail could reach around 75%. Traditional shops will likely continue to modernize and improve the quality of their offerings. The innovation ecosystem will help them to achieve better efficiency through financial and B2B supply chain digital solutions.

Opportunities for Ecosystem Players

Given the central role that traditional shops will continue to play in Africa’s retail landscape, there will be a number of opportunities for various players in the ecosystem as the environment evolves. Some are already pursuing these opportunities in the following ways:

- Private equity funds. Investment funds can find opportunities to provide capital and management expertise that will enable local modern retail chains to scale up in new cities. In Kenya, for example, private equity funds are playing an important role in backing local modern chains, such as Naivas and Quickmart, that target middle-income areas in major cities. Similar opportunities exist in Nigeria and Egypt.

- Venture capitalists and tech companies. An active start-up ecosystem is interested in providing digital solutions that will solidify the role of traditional retail in Africa and enable the sector to become the commercial interface across the continent. The payment platform Fawry in Egypt, the end-to-end solution Alerzo in Nigeria, and the digital procurement platform Chari in Morocco are good examples. Such success stories should help convince investors of the market’s potential and encourage them to fund similar ventures.

- Fast-moving consumer goods companies. It is increasingly important for providers of fast-moving consumer goods, such as food, beverages, and toiletries, to engage with the changing traditional sector to enhance their market presence. Digital solutions can help manufacturers improve their control over go-to-market strategies and provide data to better understand retailers. Unilever, Danone, and other consumer goods providers, for example, are leveraging partners such as such as TradeDepot in Nigeria and Wasoko in Kenya.

- Modern retailers. There are several ways modern chains can leverage traditional retailers to expand their footprint and better serve community needs. To increase penetration into the successful convenience store format, they can use the soft franchising model to expand their footprints in low- and mid-income areas and sell their private labels. E-commerce marketplaces can also use traditional shops as pick-up stations for goods they sell.

- Banks and telecom companies. Banks and telecom providers can achieve growth by developing new business models and offers that are adapted to traditional retailers’ needs. For instance, Kenya’s KCB Bank, in partnership with Unilever and Mastercard, launched a cashless “buy now, pay later” initiative called Jaza Duka that enables retailers to get small loans to purchase goods beyond what their working capital allows them. South Africa’s Standard Bank helped retailers gain access to public financial aid during the pandemic, and Nigeria’s Sterling Bank also offers services for traditional retailers.

- Government. The public sector can upgrade the business environment for traditional retailers by enacting policies that foster financial and digital inclusion and accelerate their modernization. For retailers who want to digitize, it can offer tax relief, favorable regulations, financial support, and training. Some African governments, such as Egypt and Kenya, tax less than 1% on sales of small traders. South Africa established the Wholesale and Retail Sector Education and Training Authority to facilitate the skills development needs of retailers. The agency provides funding, incubation support, and training programs for traditional retailers.

Traditional retailers not only are the cornerstones of African economies today but will also constitute the core of the region’s future commercial landscape. By helping traditional shops modernize and evolve to serve the changing and particular needs of their local communities, all players in Africa’s retail ecosystems will find opportunities to grow along with them—and to bring greater financial inclusion across the continent.

The authors wish to thank Adham Abouzied and Tolu Oyekan for their valuable contributions to this article.