Great design can create great value. Yet few companies examine the design capabilities of a target business—or their own. Here’s how to change that.

Smart design is like smart strategy, smart people, and smart ways of working: it’s an engine for creating business value. A mature design approach tames the complexity of products, balances function and ease of use, understands—and meets—customer needs. Yet many companies overlook design when tallying their assets and advantages. They don’t know what mature design looks like—or if they have it.

This is most apparent, perhaps, in the M&A context. Every due diligence checklist covers technological, financial, and legal ground. Yet companies rarely examine the design capabilities of a target business. They don’t explore how, or even if, design is integrated into strategy and operating models. Or whether the target’s approach to design will strengthen—or hinder—its own.

This occurs internally as well. Companies often fail to turn that same lens inward to consider the maturity—or lack thereof— of their existing design function.

Either way, the results can be costly. As competition and expectations rise, products must be useful and usable—with features that are sophisticated yet intuitive. That makes human-centered design more important than ever . And it means that whether looking inward or outward, companies must do their design due diligence, understanding how the organization views, facilitates, and unleashes design.

A Holistic View of Design

Human-centered design focuses on users and involves them closely in product development. It’s an iterative, multidisciplinary process that factors in user needs, behaviors, limitations, capabilities, and—crucially—feedback as products come together. Design due diligence serves two ends. It provides a status check on a company’s design function, and it uncovers opportunities for improvement. It’s both a snapshot and a roadmap. But what exactly does the assessment look like?

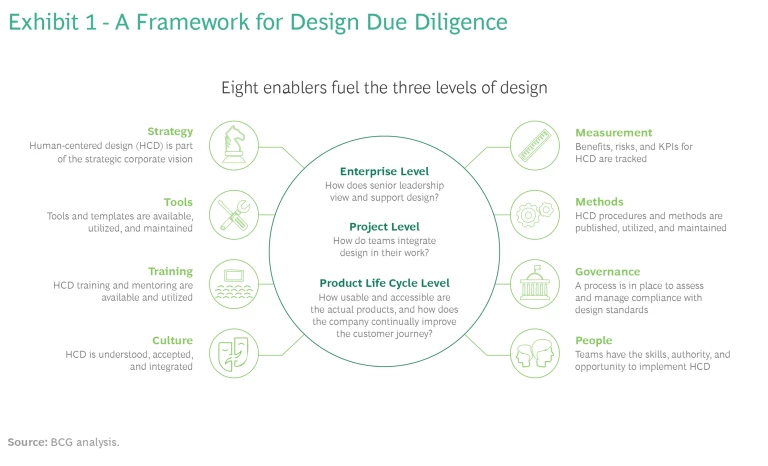

The key is to take a holistic perspective. Due diligence requires looking at how an organization approaches design on three distinct levels:

- The Enterprise Level. How does senior management view and support design? How is design incorporated into strategy and culture? How does the company measure the success of its design function and act upon its findings?

- The Project Level. How do teams run projects and integrate design into their work? How do they collaborate, iterate, and factor in user research and feedback? What tools and design methods do they use?

- The Product Life Cycle Level. How usable and accessible are the products that are produced? How does the company assess customer sentiment—and use the insight it gains to improve the customer journey and deliver better outcomes?

A mature design function excels on all three levels. Ideally, design should be ingrained in the corporate DNA, a vital component of strategy, execution, even purpose. Knowing whether you have this maturity—or where you don’t—is challenging. Companies can find themselves asking a lot of questions and, especially in an M&A context , needing answers quickly.

Companies with a mature design function have good designers and advocacy for good design that starts at the top.

To guide and speed the process, we have developed a framework for design due diligence; a way for companies to assess design holistically and gauge how they—or a company they are analyzing—stand on each level. This framework is based on our own experience in human-centered design and also grounded on a series of interviews. These discussions with design leaders at organizations at different stages of design maturity uncovered important insights on what to look for in assessing a design function.

The Elements of Design Maturity

Various elements influence the design maturity of an organization and should be considered in your assessment: strategy, culture, measurement, methods, tools, governance, people, and training. When an element is optimized, it is an enabler of design maturity. An element that is lacking will hinder maturity—and the benefits it can produce. Together, they cover the design function from beginning to end and fuel the three levels of design. (See Exhibit 1.)

By looking closely at these enablers, you can assess design from two important perspectives: management support and actual practice. Companies with a mature design function don’t just have good designers. They also have advocates for good design. That advocacy starts at the top and permeates the organization in the way it prioritizes, encourages, and enables smart, human-centered design.

For each element, there are certain questions to ask—and certain places to find answers. Typical sources include employee interviews, vision and mission statements, governance documents, organizational charts, job titles, KPIs, mentoring and training programs, and design toolkits.

What follows is a look at the design maturity elements and some guidance on how to assess them.

Strategy

Is human-centered design an explicit, integral part of the organization’s strategy? Does the company view, treat, and promote design as a differentiator? There are some telltale signs. Chief among them is leaders that have moved beyond support to true buy-in—championing and evangelizing design because they understand the difference it can make in their products, value proposition, and growth.

One thing to look for is the presence of a chief design officer (CDO) or similarly titled leader. A CDO can make the business case for design, which is crucial for executive-level buy-in. For instance, the design leader at a major international bank teamed with the chief digital officer to provide clear examples of how design makes a tangible difference to the bottom line. That laid the groundwork for building a mature—and highly effective—design function.

This spotlights an important point—and caveat. A CDO must have the ear of senior leadership, the ability to engage and show the ROI of design. It’s vital, then, to assess the authority of the design chief and to look at the interaction they have with senior leaders.

Another interview participant spoke of the difference an empowered CDO can make. When the company—whose founder believed deeply in the value of design—hired a design chief, it gave them the authority to build a team and a design system to tackle scaling challenges. With this power, the design chief quickly built the mechanisms for incorporating design into the organization’s operating model—and mindset.

Culture

Design maturity requires having a design mindset. The organization accepts and integrates human-centered design as regular practice; it’s part of the culture. Understanding the customer—through research, feedback, and other means—is seen as a priority and a key value throughout the business.

One design professional told us how their company has an advisory group of customers in every geographic region in which it operates. These groups provide necessary feedback at monthly meetings. Participants at an annual customer gathering offer additional perspective. Companies employ a variety of tactics, but the goal is the same: to keep learning about customers and use those insights to create responsive product designs and fuel improvements.

Design—and designers—should be an integral part of the product life cycle, from development to deployment to upgrades.

At the same time, you want to ensure that the culture fosters collaborative and iterative ways of working. The idea is to empower cross-functional teams that seek out and incorporate feedback as they create and improve products. Design—and designers—should be an integral part of the product life cycle, from development to deployment to upgrades. Many organizations have embraced agile ways of working , which emphasize collaboration, frequent iteration, and responsiveness to feedback and changing requirements. Look for agile methodologies and an agile culture as part of your due diligence. Just make sure that when teams say they’re cross-functional, those functions include design.

Measurement

Are design capabilities, goals, and ROI assessed regularly? A strong design function is dynamic: an organization’s design capabilities—and the ways in which they are deployed—continually evolve. Understanding what works, what doesn’t work, and how to improve requires rigorous and constant measurement. A company must identify quantifiable objectives for human-centered design and monitor whether it is meeting, exceeding, or trailing those goals. In your due diligence, you want to ensure that on an enterprise level there is a mechanism—and a mandate—for ongoing assessment.

Determining the appropriate metrics isn’t always straightforward. While many companies look to customer loyalty scores to measure the overall customer experience, others find that Customer Effort Score (CES) and Customer Satisfaction Score (CSAT) can provide more focused measurement and insight. Still others use highly specific sub-metrics, which let them zero in with precision on strengths and weaknesses. So look closely at what the organization is—and isn’t—tracking. The best metrics not only provide feedback and direction, they also demonstrate the power of design, which generates more support and more champions. For example, one company adopted a metric of “number of features removed.” By calculating the cost of maintaining various features and analyzing the real value-add to the customer—and removing costly, nonessential ones—design leaders readily, and visibly, demonstrated the business value of design.

Methods

Does the company have a well-defined, human-centered design process? Our interviews spotlighted the need for design standards: documented practices that project teams apply in a consistent way. In your assessment, look for repeatable methods and robust design systems as well as an approach for selecting, publishing, and maintaining design procedures, tools, and frameworks. You want to ensure that human-centered design is integrated into the overall project plan and that there is effective communication between those responsible for design and other members of project teams.

Tools

Does the company have—and make readily accessible—tools and templates to facilitate human-centered design across the organization? In addition to the tools themselves, you want to look for a mechanism for providing guidance on selecting, adapting, and applying those tools. Style guides, design systems, and a center of excellence (COE) can provide evidence of how a company promotes and maintains the infrastructure for design—and how it helps teams unleash their talent and the power of design.

Governance

The most robust methods and tools won’t be of much use if teams don’t apply them appropriately. Part of design due diligence is looking at how a company assesses and manages compliance with its design standards. How does it identify deficiencies? What are the mechanisms for taking corrective action?

We’ve found that a COE can be a powerful asset in keeping everyone up to speed—and on the same page—regarding design practices and tools. Through guidance and coaching, a COE not only promotes consistency and compliance, but also innovation.

People

Talent fuels every engine of growth. Does the organization recruit and cultivate sufficient design talent? Do designers have the authority—and the opportunity—to implement proper practices? Looking at org charts can be helpful, but titles alone don’t tell the full story. You want to understand roles and responsibilities, levels of influence and empowerment. Who makes decisions about design—and what is the process or chain for decision making? You also want to look at hiring goals and standards, at how design experts are integrated into project teams, at the mechanisms for cross-functional collaboration.

One of the more revealing findings from our interviews was the emergence of the designer-to-engineer ratio as a harbinger of success. While there is no textbook number, the collective sense we took away from interviews is that if the ratio is too strongly biased towards engineers (say 40:1 as opposed to 12:1 or lower), then designers can’t be successful.

Training

Does the company have and effectively utilize training and mentoring for design? Organizations that help their talent evolve and master new techniques and technologies reap the fruits of their efforts. What to look for here? Onboarding programs, training courses and budgets, reference libraries (physical or digital), and mentoring programs can all shed light on how an organization approaches development of its design talent.

A maturity assessment helps companies see how the pieces of the design function fit—and where to focus improvement efforts.

In interviews, participants noted the importance of an institutionalized design critique: a mechanism for generating feedback within teams on what is working, what isn’t working, and how to improve designs. Crucially, this should be an informal, low-preparation peer review. The idea: make it easy, and a matter of course, to spark conversations and actionable insights.

Finding Your Path to Value

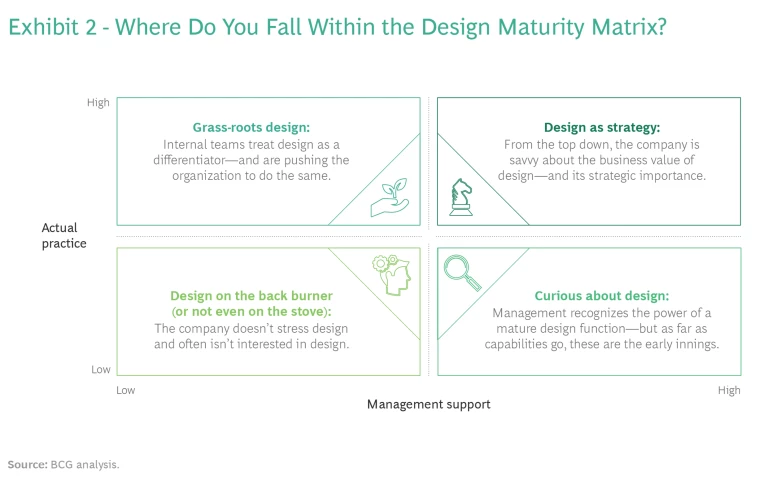

In our work, we use the framework to plot companies along a design maturity matrix. (See Exhibit 2.) While organizations may start out in the lower left quadrant, their journey can take multiple directions. Some companies are better served by focusing on actual practice: developing a core of committed, motivated designers and building grass roots support, which then becomes a springboard for gaining management support. For other companies, it makes more sense to prioritize management support and leverage that for budgets, hiring, and training.

The maturity assessment is all about providing direction. For companies looking inward, it’s a way to see how the pieces fit—or fail to fit—together, to understand where to focus improvement efforts. In an M&A context, design due diligence shows you how the target’s approach and capabilities mesh—or clash—with your own.

In all contexts, conducting this analysis has value because design itself can generate value. Smart design makes it easier for customers to understand, use, and unlock the power of products and services. And that’s increasingly important as those offerings get increasingly complex.

Design due diligence may add to your to-do list—but it can also boost your competitive edge and growth. Great ideas can put a company on a map. Great design can set it apart.