The risks children face online are growing, and the current responses aren’t nearly enough. Fixing the problem will require a comprehensive global strategy.

With online access virtually ubiquitous on computers, smart phones, tablets, and other mobile devices, almost all children under 12 are now internet users. As these children spend more and more time online—a trend that has only accelerated since the COVID-19 pandemic began—the cyber risks they face, such as online bullying, inappropriate content, and digital addiction, are worsening.

Efforts to respond with increased awareness and protective measures are growing, but they are not nearly enough. Child protection in cyberspace is an urgent issue that needs immediate attention and more targeted responses than we have seen to date.

Given the gravity of this problem, BCG set out to examine children’s online vulnerability in different regions. We wanted to know where and why protection is lacking or breaking down, the factors influencing the global response to the problem, and which solutions might be appropriate. To answer these questions, BCG did a thorough review of the existing research on cyber threats to children, amplifying it with a global survey of 41,000 parents and children. (See “About the Survey.”)

About the Survey

The regional breakdown of survey respondents was: Asia-Pacific (11,700); Middle East and North Africa (8,400); Latin America (7,600); Europe (7,200); North America (5,300); and sub-Saharan Africa (900). Among the 61% of respondents who were children, 9,000 were age 8 to 11, 8,300 were age 12 to 15, and 7,800 were 16 or 17. The remaining 39% of respondents were parents with children aged 8 to 17.

Our research found that:

- Online threats are endemic, and they affect a substantial number of children. What’s more, several intractable trends will likely exacerbate the problem in the near future.

- Most of the programs dealing with cyber threats focus on one aspect of the overall issue—for instance, online sexual abuse. Coordination among these programs must be improved across regions and governments to reduce duplication of efforts and improve results.

- There is a bright side, though. Based on our survey data, a broader picture of the extent of cyberspace dangers for children is coming into view—and a blueprint for making the online realm a safer place for children is starting to emerge.

A Broad Range of Threats

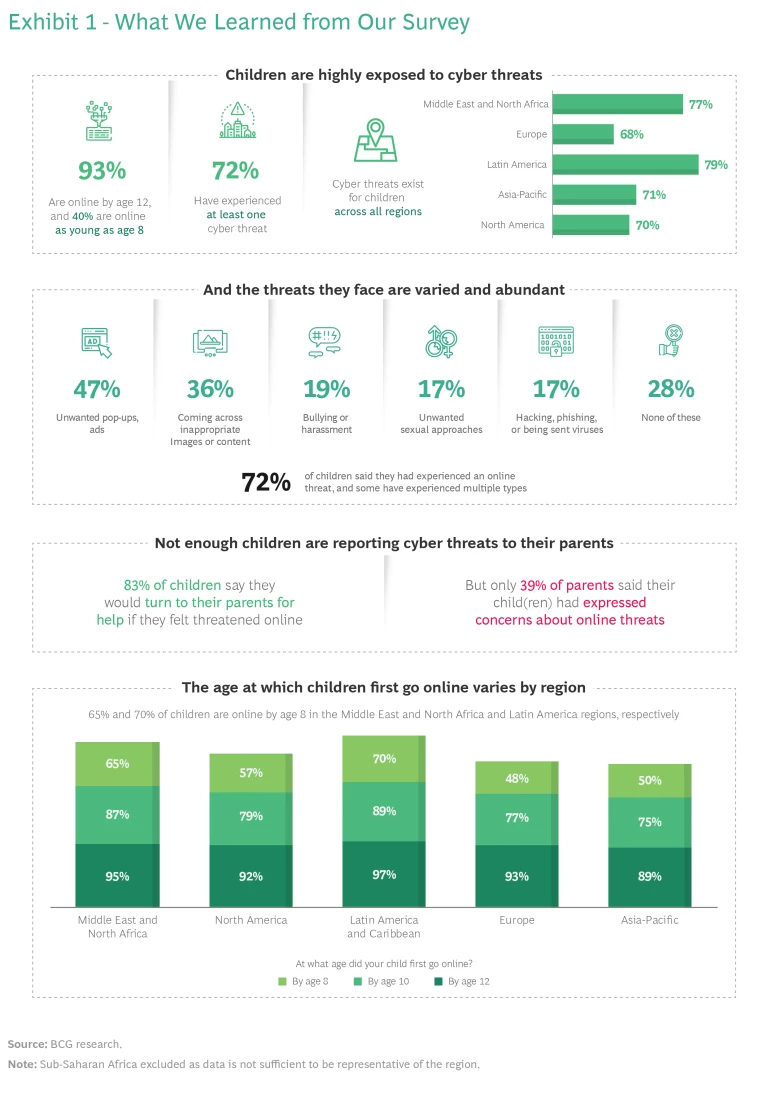

As many as 93% of children from ages 8 to 17 are on the internet, our survey results indicate. Remarkably, nearly three out of four respondents said they had experienced at least one cyber threat. (See Exhibit 1.)

Despite the frequency of such threats, most incidents aren’t being reported. Only about 40% of parents said their children had expressed concerns about inappropriate content they had encountered online. At the same time, more than 80% of children said they would go to their parents for help in those circumstances. This suggests there may be certain barriers—such as being uncertain about what an online threat is, or possibly a fear of speaking out—keeping children from reporting cyber threats.

So what, exactly, constitutes a threat? Today, discussions of child safety online—and programs that attempt to address the issue—tend to be heavily skewed toward the dangers of online child sexual abuse and (to a lesser extent) on cyber bullying. The risks children face online go well beyond these significant areas, however.

A widely accepted categorization of those risks—and one we feel is sufficiently comprehensive—was advanced by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and then adopted at various stages by UNICEF and many other organizations. This framework views the issue through four categories:

- Content, including exposure to illegal and age-inappropriate content, embedded marketing, and online gambling.

- Contact, including ideological persuasion; exploitation (sexual abuse and trafficking, harassment, and drug addiction); and violation and misuse of personal data.

- Conduct, including cyberbullying and the effect on children of excessive screen time and owning digital devices.

- Consumer, including marketing, commercial profiling, financial, and security risks.

Besides the obvious dangers inherent in each of the “four C’s” above, there are risks such as privacy intrusions that span all categories. Regardless of how one classifies the risks, they can have a dramatic impact on children’s health and well-being. In the mental health arena, victims of cyber bullying are up to 160% more likely to attempt suicide, according to the DQ Institute. And studies have linked excessive screen time to delinquency, low grades, risky behaviors, depression, and anxiety.

Physical outcomes for children with overly active cyber lives are problematic as well. Too much time on the computer can lead to higher body-mass scores and obesity, the inability to meet basic fitness guidelines, and even chronic conditions such as poor back-muscle endurance.

These problems will only worsen if we don’t take immediate steps to manage online risks. Children’s potential exposure to cyber threats is rapidly increasing; during the pandemic, the internet has become one of the primary channels for daily education, with two-thirds of children surveyed saying they use their schools’ online platforms daily. Additionally, emerging technologies , such as the Internet of Things or cloud-based and network-connected devices—including wearables, household appliances, toys, and robots—will likely lead to a new set of threats. These items are essentially always online, and they increase the potential for children to be exposed to cyber risks, including the abuse of private data such as location and usage patterns.

What the Data Tells Us

As we delved into the existing research, we felt it was important to validate and expand upon our findings with global data that could provide a clearer picture of children’s online behaviors. We also wanted to understand the scope and frequency of specific online threats and how children and their parents have reacted to them. Gathering such data is an essential foundation for designing coherent and broad-based solutions that are informed by actual online behaviors. Additionally, it allows us to develop strategies that target specific online dangers faced by children and the role that ecosystem participants can play in minimizing these threats.

The anecdotal evidence and existing research that needed to be quantified included global data on children’s online activity; children’s awareness and behavior towards online threats; children’s experiences with threats; parental responses to these threats, particularly when alerted by children; and how online usage and threats differed in developed and developing countries. To collect this data, we surveyed some 41,000 children and their parents. Our survey followed the OECD’s revised typology of online threats—content, contact, conduct, and consumer—and the questions focused on specific areas of vulnerability within these categories. Here’s what we learned.

Online Behavior and Fears. While the top-line data points about children’s online activities and the threats they face are troubling in themselves, a deeper examination of the survey responses reveals a problem with many nuances and pain points that need to be addressed directly.

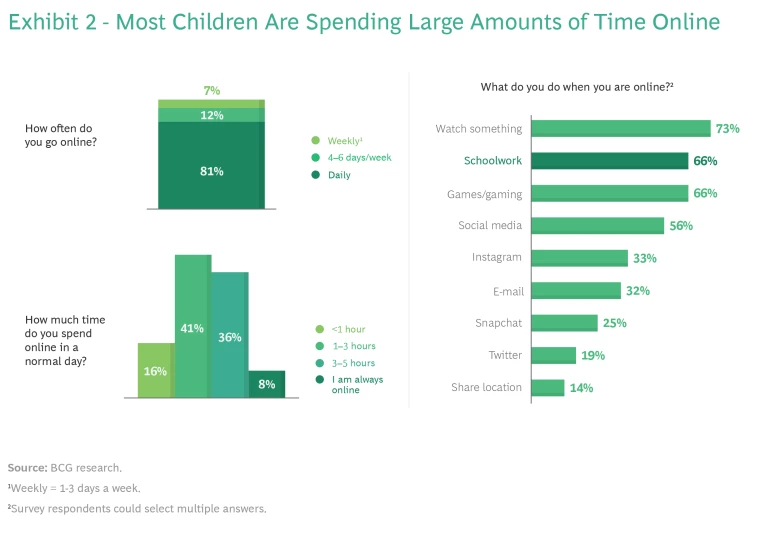

For example, while it’s eye-opening enough to consider that almost every child anywhere in the world is on the internet by age 12, the potential risks are magnified by the fact that 81% of children go online daily—with almost 45% of them more than three hours per day. (See Exhibit 2.) Perhaps most concerning: when not doing schoolwork, children’s online time primarily revolves around activities where threats could most likely fester. These include watching videos, movies, or streaming television, gaming, and social media. Beyond these threats, frequent online engagement is negatively affecting children’s physical conditions and mental health.

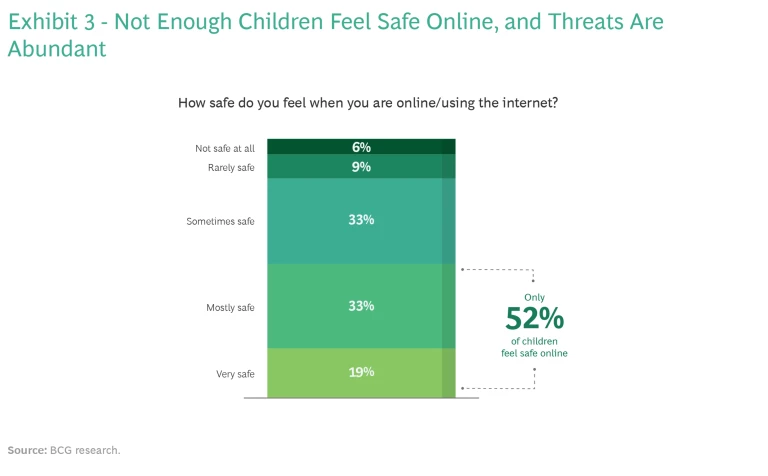

With most children accessing the internet daily, we want them to feel unthreatened when navigating cyberspace and to be aware of how to avoid and respond to cyber risks. However, only half of the children we surveyed feel safe while online. (See Exhibit 3.) That shouldn’t be surprising, given that 72% of children surveyed have experienced at least one online threat. The most prevalent cyber threats were unwanted ads and inappropriate images and content. In addition, nearly one in five children said they faced bullying or unwanted sexual approaches.

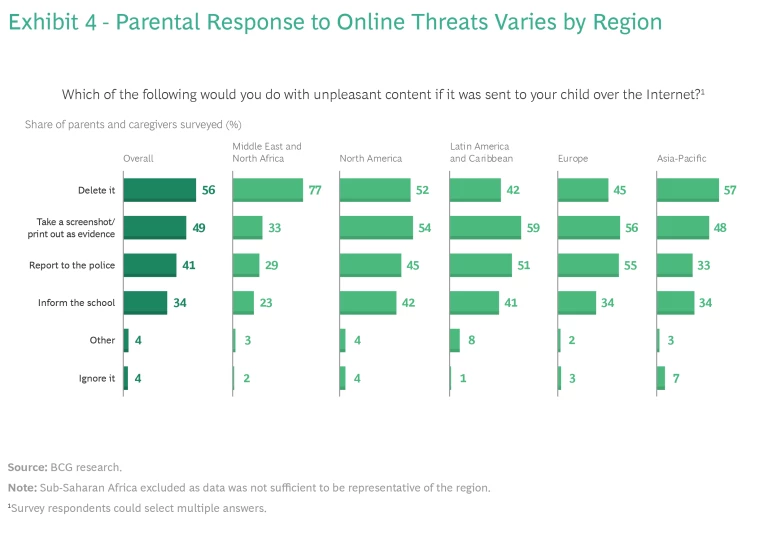

How Parents Respond—or Fail To. Given the serious nature of cyber threats and the high number of children who have experienced unsafe activities online, the fact that only about 40% of parents said that their children have told them about these types of incidents is disturbing. But perhaps even more troubling is that when parents become aware of their children receiving or coming across unwanted, unpleasant, and malicious content, measures taken are often reactive and are skewed toward deleting content (56%) rather than reporting it to the police (41%) or informing schools (34%). Without a higher degree of transparency about the number of threats and their nature, ecosystem participants will be unable to respond adequately and develop enhanced preventive measures to keep children safe online.

Of course, parents are a critical frontline element in protecting children online—and in this regard they appear to be more vigilant about setting rules concerning amount of time spent on the internet than in actually monitoring their children’s online activities. About three-quarters of the children said that their parents have placed limits on their internet usage. But only 60% of parents said they regularly check how their children are using their connected devices, with “regularly” defined as once a week or after every use. Indeed, 20% of parents said that they track activity once a year at most. And while virtually all parents responded that they are familiar with control mechanisms that can impede their children from engaging in specific types of potentially risky activities online, only about half said that they actually use these parental tools.

The Regional Divide. The primary reason for our research into online threats was to fill in data gaps pertaining to children’s online activities and the threats they face globally. However, our survey has also revealed regional and even country-level nuances that should be considered when implementing solutions. For instance, 70% of children in Latin America are already online by the time they are eight years old; 65% of children in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) are online by that age. That compares to only 50% in Asia-Pacific and 48% in Europe. Not surprisingly, children in Latin America and MENA have also suffered the greatest number of cyber threats. As many as four out of five children online in Latin America say they have been victims of at least one incident.

It is perhaps some consolation that the highest degree of parental monitoring occurs in MENA, where the number of cyber threats is elevated. In that region, 65% of parents regularly monitor the online life of their children, and more than 50% of children and parents routinely discuss internet usage and activities. By contrast, parental monitoring is lowest in Asia-Pacific, where only 46% of parents said they regularly examine how their children are using the internet. This figure is troubling, because only 35% of children in Asia-Pacific said that they and their parents talk openly and regularly about what they do online. Also, only one-third of parents said they would report cyber threats to the police. In Europe and Latin America, that number rises to about 50% of parents. (See Exhibit 4.)

All of this paints a picture of a cyberspace environment in which dangers to children are prevalent. But parents and children are somewhat at sea about how to communicate with each other and with authorities—and how to respond to threats. Moreover, on the whole, schools are not meeting the challenge of equipping children with the tools and skills they need to navigate and address cyber risks. Less than 60% of children said their schools provide workshops and other programs related to online safety. Similarly, national awareness campaigns targeting children are also lacking, with only around half of the children surveyed saying they have seen campaigns on TV or billboards in their country.

Current Initiatives Are Making Progress—but Gaps Remain

As part of an effort to generate an overall strategy for dealing with these issues, we also conducted an extensive assessment of the more than 60 organizations focused on protecting children in cyberspace. We reviewed key global efforts across all aspects of society, the research and data they have produced, and the leading global events and conferences they have sponsored.

We found a lot of strong, engaged, and energetic initiatives that are contributing to making cyberspace safer for children and to better supporting those who have been threatened online. Among the initiatives:

- UNICEF’s efforts include two multipartner projects, Global Kids Online and Disrupting Harm, which assess the risks of child abuse online and potential measures to combat it.

- The International Telecommunication Union, a U.N. organization, launched the Child Online Protection initiative in 2008. The initiative, a multistakeholder effort within the Global Cybersecurity Agenda framework, brings together international partners from all sectors of the child protection ecosystem to create a safe and empowering online experience for children around the world.

- WeProtect Global Alliance (WPGA) is an independent international institution focused on ending child sexual abuse online. It drives action through its Global Threat Assessment and national and global response frameworks, amplifying the voices of children and survivors of abuse and supporting collaboration. WeProtect was founded in 2016; its membership includes 99 countries, several major international organizations, 59 private sector companies, and 77 civil society organizations. Alliance members will meet to renew their commitment to tackle child sexual abuse online at the annual WPGA summit in 2022.

- DQ Institute, a think tank headquartered in Singapore, is committed to setting global standards for digital skills and safety. As of 2020, the organization’s #DQEveryChild campaign, a global digital citizenship movement for children, had reached more than 80 countries in collaboration with more than 100 partner organizations. The Institute has also established a child online safety index covering 30 countries worldwide and has developed a global standard for digital literacy, digital skills, and digital readiness.

- OECD, an intergovernmental organization with over 35 member states, developed the “four C’s” framework for classifying online risks and a recommendation for the protection of children online—the latter of which was adopted by the G20 within a regulatory agreement to facilitate the exchange of data.

While these organizations and many others are doing valuable work, our research indicates that there are still crucial gaps that must be addressed in order to tackle child protection in cyberspace holistically and comprehensively. One such gap is the lack of available standardized data. Surveys conducted by these groups have tended to include small regional subsets of children’s activity online or to examine only thin slices of the significant threats children face overall. In addition, these surveys often cover different age groups—for instance, one may look at 8- to 12-year-olds, another at 15- to 24-year-olds—making it difficult to tease out which children are most at risk or to compare results.

There are a variety of reasons for the somewhat limited efficacy of organizations attempting to address the problem of child protection online. For one thing, many of them are siloed nonprofits and struggle to gain the needed funding and build the necessary broad-based ecosystems to aggressively tackle this issue—a shortcoming that could be addressed by more international cooperation as well as more active and committed private sector engagement, particularly from tech giants such as Facebook, Google, Microsoft, and Apple as well as gaming companies. In addition, online child protection efforts are more advanced in higher-income countries, while many of the worst threats exist in less-wealthy regions, where a greater number of kids tend to be online from a younger age. And the focus of these efforts—and of the investments they require—tend to support reactive measures as opposed to prevention initiatives.

For global organizations to be fully effective in addressing the problem, they must adopt collaboration strategies that more openly foster ongoing global dialogue on cyber threats, joining with each other to strengthen and expand their activities and reduce duplicative efforts. The standardization of data and metrics is essential, as is transparency and sharing; this will allow organizations to better measure results and progress as well as to implement new online safety protocols and policies. Among other things, our primary research has identified a clear need to increase national and international awareness campaigns that offer children information and advice about both reacting to and preventing cyber threats.

How Stakeholders Can Help Protect Children Online

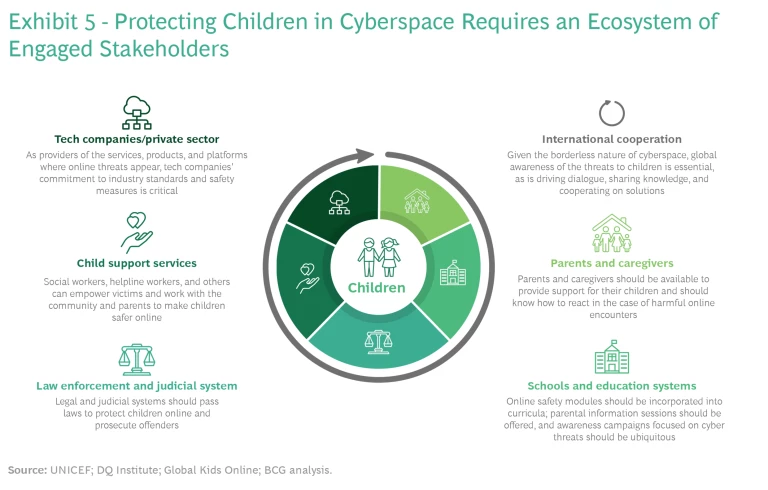

The activities of international organizations can play a crucial role in making children safe in cyberspace, certainly. But any effort to address the problem will fall short without engaging all the participants in the online ecosystem. Aside from international organizations—which should play a plenary role anchoring global research and cooperation—these participants include the private sector, especially tech and gaming companies; children’s support services and NGOs focused on online safety; law enforcement and the judicial system; parents and caregivers; schools and education systems; and, at the center of the ecosystem, children themselves. (See Exhibit 5.)

Based on our extensive research—including our survey and an analysis of existing initiatives and gaps across the child protection ecosystem—BCG has come up with a series of recommendations for each of these central players that could serve as a starting point for a comprehensive, global strategy.

Tech Companies and the Private Sector. We have seen some recent movement from global tech companies, such as TikTok for Younger Users—a program that provides children under 13 with additional privacy and safety features while using the service, including restrictions on commenting and posting content. However, there is still an urgent need for tech giants—whose hardware and software are the entry points for children online—to increase their efforts to protect children. Tech companies should collaborate more, set industry standards, and develop innovative solutions to tackle risks. Safety mechanisms should be built into products and services that kids are most likely to use; in addition, the private sector should develop systems to monitor and publicly report on cyber threats and incidents—providing increased transparency on the extent and types of problems children face and, in the process, allowing for more targeted solutions.

Law Enforcement and Judicial Systems. Cyberspace threats are buoyed by fast-paced tech innovations that are implemented more rapidly than the laws and regulations meant to police them. The situation is aggravated by the fact that cyberthreats to children cut across borders—and there is only limited international law enforcement cooperation on these matters. Moreover, protecting children online is typically less prioritized as a national issue in developing countries, whether due to a lack of resources and funding or because other problems are considered more urgent.

Existing law enforcement frameworks must be expanded and adopted at national levels, and they should be continually updated to recommend best practices and new technologies for policing and prosecuting online threats to children. New national legal frameworks should be developed where none yet exist; small communities cannot tackle the problem alone without national funding, technical support, and response teams. In addition, national law enforcement authorities should seek international cooperation to better prevent and respond to cyber threats, which are more likely to be cross-border incidents than local activities.

Child Support Services. Only a few countries, such as the UK, US, and Australia, have mature systems in place to train and educate child support staffs in best practices for protecting children online. In many countries, barriers—including lack of knowledge about what support is available and stigmas that dissuade parents and children from even discussing the issue—stand in the way of providing services that could help in dealing with online threats.

The first imperative for child support services is to upskill their staffs, educating them about the online threats children face and how to police them. Next, these agencies must increase the awareness of the issue in their communities and let children and parents know what support is available to address, monitor, and report cyber threats. As our survey showed, children do not tell their parents often enough about cyber threats they have encountered—so support services should also work to proactively overcome any hesitance for children to talk freely about such incidents.

Schools and Education Systems. Some countries have adapted education programs and curricula to cover digital skills and competencies. But even these programs fail to provide tangible training in, and solutions to, online risks—what they are, where they exist, how to react to them, and how to avoid them. Moreover, education systems are not working with parents to keep them informed and up to date on the latest threats.

Online safety modules should be incorporated into K–12 curricula in all countries; parental information sessions should also be offered by schools, and awareness campaigns focused on cyber threats should be ubiquitous. Equally important, schools should offer digital literacy courses to ensure educators are up to date with the latest technological developments and cyber-risk dynamics.

Parents and Caregivers. Parents have insufficient awareness of the threats faced by children online. And most parents lack the knowledge, training, and skills with regards to the best methods and tools for protecting kids. Like law enforcement, parents are having a difficult time keeping up with advances in technology. And in many cases, parents are hesitant to bring up and openly discuss sensitive topics with their children.

With all of this in mind, educating parents on these issues is crucial. Survey results clearly indicated that parents do not monitor the online activities of their children closely enough, nor do they report incidents to authorities often enough. Materials and training sessions are essential to teach parents about new technology and platforms their kids are accessing; about online control mechanisms and the latest hardware and software features for protecting young internet users; and how to communicate better with their children about online behavior and threats. The parents we surveyed expressed interest in receiving such information and guidance from websites (54% of respondents), their children’s schools (49%), and internet service providers (44%).

Child protection in cyberspace may not have gotten the full attention it deserves in the past few years. But the relentless and insidious increase in the types of threats children face—and in the number of incidents that have occurred—makes confronting the issue an imperative. BCG’s in-depth survey of children and parents and our analysis of the online-safety ecosystem have attempted to crystallize the scope of the problem and what is being done to address it. Out of this we have synthesized an immediate action plan, including:

- Increased efforts to make the public aware of the magnitude of the problem and what they can do about it. Tech giants bear a particular responsibility to educate their users about cyber threats to children and the safety features available to them.

- More stringent rules and more rigorous policing of potentially dangerous online activities.

- New technologies to monitor and protect children.

- Better communication about the issue and its implications among parents, children, educational systems, and international organizations.

- More robust efforts by technology companies and social media platforms to protect children using their products and services, including the ongoing development of new safety features.

It may seem like a lot to take on—and, in fact, it is. But the repercussions of not taking cyber threats against children seriously enough or failing to face those threats effectively—measured by the toll on children’s safety, quality of life, development, and health—would be harder still to accept.