Strategy has started playing an important role in the public sector. It is used by a growing number of government organizations in different

In fact, after classic bureaucracy, professional rule, New Public

The chief characteristics of a strategic state are leadership from the center (with the revival of grand strategy and whole-of-government orchestration), responsiveness to the voices and choices of citizens, a mission to create public value, transparency in setting and pursuing objectives, a focus on implementation, and broad collaboration with public, private, and international partners. Pioneering strategic states, such as Singapore, South Korea, Japan, and the Scandinavian countries, have shown that embracing some or all of these elements can indeed greatly improve the delivery of public value.

Empirical evidence indicates that investing in strategic capabilities helps public agencies improve performance.

Empirical evidence indicates that investing in strategic capabilities helps public agencies improve

Yet the need for governments to step up their strategy game is growing urgent, with a confluence of crises at their door. Even as they continue to deal with the lingering effects of COVID-19, inflation and economic downturn are presenting new challenges. Structural problems that have long simmered in the background, such as climate change, depleting resources, and demographic change, are rapidly becoming more imminent. At the same time, the resources available to government are dwindling . The years of capital and labor abundance have come to an end, owing to rising interest rates, demographic aging, and increasingly fierce competition for talent. Geopolitical tensions are on the rise and multilateralism is at an all-time low. Many democratic governments are facing a crisis of legitimacy , which is causing political gridlock that further undermines the ability of these governments to strategize and act decisively.

Public agencies need to do more with less—and they are struggling to make it work. Trust in government is historically low.

As a result, public agencies need to do more with less—and they are struggling to make it work. Trust in government is historically low. The Edelman Trust Barometer, a survey of more than 36,000 respondents in 28 countries, found that in 2020 only 65% of people trusted their government; this figure fell to 52% in 2022. For comparison, trust in businesses and NGOs was relatively stable during the same period. Other evidence, such as a May 2022 Pew Research Center survey of US adults, suggests that this sharp decline is driven not by decreasing trust in politicians (that trust has always been low) but by a drop of confidence in civil

To navigate this era of complexity, uncertainty, and scarcity, and to restore the public’s confidence, governments need to accelerate their progress toward becoming strategic states. In our experience, three principal challenges stand in their way:

- Going beyond “strategy as planning”

- Choosing the right strategic approaches for each agency’s environment

- Using strategy to bridge the gap between policy and implementation

Overcoming these challenges will result in a revitalized and more effective praxis of strategy.

Going Beyond “Strategy as Planning”

Strategy used to be more straightforward: one would analyze a situation, set goals, make an enduring plan to achieve them, and then execute that plan. The strategy would be reasonably stable in the long term, and with systematic efforts, goals could be met.

This conceptualization of strategy as long-term planning is still deeply entrenched in government today. In some cases, it is hardcoded into legislation. For example, the Government Performance and Results Act in the US requires public agencies to submit five-year outlooks, run an annual planning cycle, and work with fixed performance metrics. The Turkish Strategic Planning Guide requires agencies to submit a five-year estimated cost

While the perception of strategy as planning is still dominant in government, it is often a poor fit for today’s public agencies. Four developments have reshaped the context for strategy and have led to new opportunities and risks that strategic approaches need to take into consideration.

THE FOUR DEVELOPMENTS

Agencies need to reckon with an increasingly unpredictable world. Developments in technology, globalization, and other areas have drastically increased the connections among different geographies and across economic, social, and natural

The accelerating rate of disruption has also led to increased malleability of the context. As structures are continuously changing, governments have greater opportunities to influence them and to rewire different aspects of society.

Consider the smart city. Historically, cities had few tools available to direct traffic flows—limited, for example, to road signs and traffic controllers. Today, geospatial data allows local governments to read traffic flows in real time and prevent congestion with automated interventions such as closing roads, adjusting traffic lights and speed limits, and updating itineraries in the navigation systems of cars. In other words, traffic in cities has become much more malleable. In this and other malleable environments, the strategic approach should not just be to plan against an anticipated future but also to envision and shape that future.

The confluence of unpredictability and malleability leads to a greater imperative for collaboration. A fast-changing and malleable world offers governments much greater and more varied ways to shape society, but they cannot deliver on this on their own. Public-private ecosystems are emerging as a new strategic approach because they can reshape society on a large scale under uncertain and dynamic conditions.

The need for collaboration is further reinforced by the increasing interdependence of the public and private sectors. Planetary boundaries and resource shortages are presenting new collective constraints that public and private organizations need to grapple with together, while advances in communication and data technologies allow them to coordinate more frequently and more precisely and at higher levels of complexity. In the words of professors of public administration Jan Kooiman and Martijn van Vliet (both early observers of this trend), “Complexity, dynamics, and diversity has led to a shrinking external autonomy of the national state combined with a diminishing internal dominance vis a vis social

Indeed, we see that public and private domains are converging in practice as more companies are engaging in

corporate statesmanship

, while governments with dwindling resources rely on public–private partnerships to provide social goods. Many public agencies now find themselves operating in domains they cannot control through their own actions; rather, they can only influence them by orchestrating a network of partners—in other words, steering instead of

The resources of many governments are under pressure. Agencies operating in policy domains that receive less political priority will often receive less funding and therefore will need to use regenerative strategies to maintain viability and relevance.

BEYOND “STRATEGY AS PLANNING”

The developments—increasing uncertainty, malleability, interdependence, and scarcity—create a need for new strategic approaches. While “strategy as planning” is still useful in some specific situations, agencies can no longer default to it unquestioningly.

Choosing the Right Strategic Approaches for Each Agency’s Environment

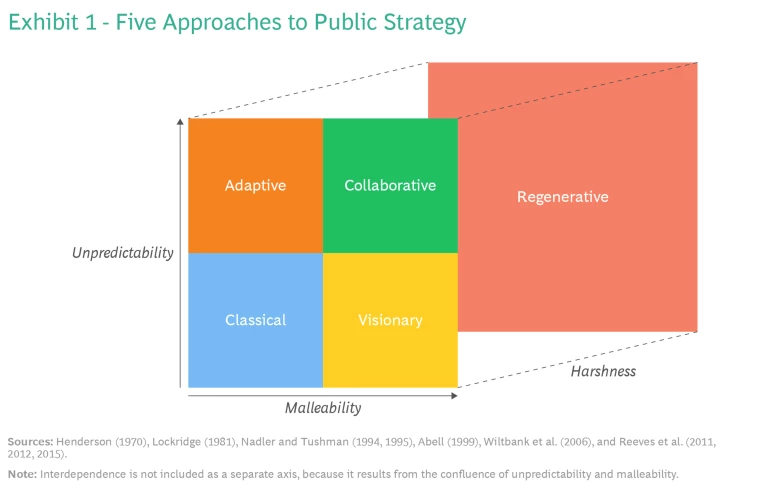

Increases in unpredictability, malleability, interdependence, and scarcity are broad societal trends, but their effect is not uniform across domains. Some domains, such as road maintenance, remain relatively stable and predictable; others, such as cybersecurity, are highly volatile and uncertain. Agencies seeking to use strategy effectively need to differentiate their strategic approach based on the requirements of their specific environment. The different strategic approaches, already applied in the private sector , are summarized in Exhibit 1.

To choose an approach that works well in each environment, an agency needs to break free of its traditional methods. The five strategic approaches that are optimal in different situations each requires entirely different capabilities, processes, and tools. That means it is ineffective for an agency to default to a traditional planning process; rather, it should choose the strategic approach and process based on the requisites of the environment.

THE FIVE APPROACHES

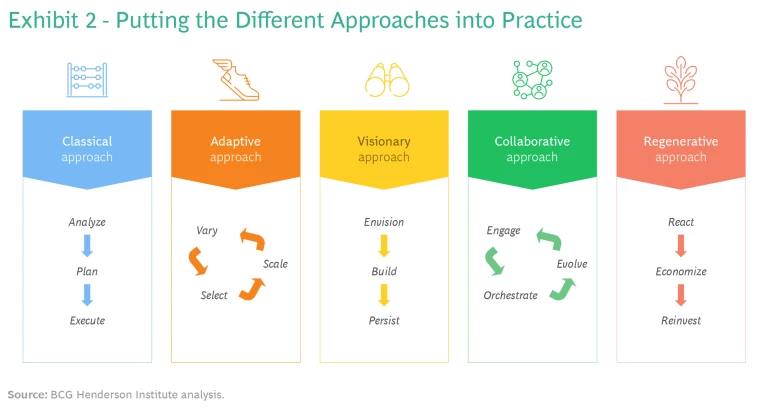

Classical. Agencies operating in environments with low unpredictability and low malleability should follow a classical approach to strategy. In the absence of malleability, the agency should focus on operating within rather than reinventing its domain—and given the predictability of the environment, such operations can be planned. The essence of a classical approach is to analyze, plan, and execute. Examples of agencies well suited to a classical approach could include tax agencies, railroad operators, the prison system, and water authorities.

To succeed with a classical approach, it will be important to have a strong administrative center, a cyclical planning process, clear targets, and rigorous performance management. Innovation is often limited and focused on specific needs. Discretion at the frontlines is restricted. Agencies with a classical strategy often focus on scale and vertical integration to deliver a service or product at low cost.

Adaptive. Agencies that face a highly unpredictable, nonmalleable environment should follow an adaptive approach to strategy. Long-term planning is senseless in the face of volatility and uncertainty. Strategies should instead focus on building resilience to withstand crises and change. The essence of an adaptive approach is to vary, select, and scale. Agencies that may benefit from an adaptive strategy include immigration centers, disease control agencies, cybersecurity teams, organized crime departments, and financial market regulators.

Adaptive agencies should steer clear of long-term plans, fixed goals, and overly detailed performance metrics. Instead, it is important to deploy time-limited, bespoke teams; use scenario-based approaches; and foster a disruptive culture. Teams at the frontlines should have a high degree of discretion to respond to signals in real time. Open communication from leadership is essential to continuously re-align the organization around emerging priorities. Civil service rules should take a backseat to allow for the exploration of new, unorthodox solutions. Strong feedback mechanisms are required, such that experimental solutions found to work well are funneled back to the core and disseminated across the organization.

A successful example of an adaptive approach can be found among the police forces in Victoria,

In response, the police forces went through a major reorganization to improve their adaptiveness to shifting patterns of crime. The reorganization focused on fostering collaboration across squads, including periodic rotations of staff, temporary interdisciplinary teams, and new training activities beyond specialist skills. Although initially controversial, the new focus on cross-team collaboration and the open exchange of information significantly improved the police forces’ ability to quickly adapt to criminals’ changing tactics.

Visionary. Agencies that operate in a relatively predictable and malleable environment should follow a visionary approach to strategy. The approach can be summarized with the words of Peter Drucker: “The best way to predict the future is to invent it.”

A visionary strategy is relevant to agencies in a position to single-handedly reshape their domain. The essence of a visionary approach is to envisage, build, and persist. Examples of agencies where a visionary strategy may be appropriate are spatial planning offices, housing authorities, public investment banks, and coordinators of development aid.

Visionary agencies should focus on harnessing the imagination of employees and partners. This can be a tricky process, especially in large organizations. Employees are typically rewarded for following a dominant narrative—because it gives a higher likelihood of getting projects approved, receiving praise from colleagues, or getting a promotion. And, by following the narrative, they in turn reinforce it. This vicious cycle is detrimental to the ability of public agencies to creatively envision different futures for their domains.

The visionary approach is aimed at breaking the cycle. It is important to seek out surprise—to move outside of your own organization and involve innovators, such as entrepreneurs, civil society figures, and younger generations, in the strategy process. The analyses that serve as inputs for the strategy should focus more on anomalies than on established trends so that there is attention for newer developments and alternative courses of action.

After an initial phase of divergence, the organization needs to coalesce around a new vision for the future that is coherent, rigorous, and concrete. Over time, the strategic vision can be remolded through a dialectic process, but changes should be infrequent and purposeful to avoid confusing employees and partners. The visionary approach requires a deliberate process that is best managed professionally through a dedicated strategy unit. This unit takes care of the process side, while allowing civil servants with subject matter expertise to participate from a content perspective.

BCG Henderson Institute Newsletter: Insights that are shaping business thinking.

A successful example of a visionary approach is found in

Part of the strategy was to invest heavily in public-private partnerships to build modern IT infrastructure and design digital public service delivery. To entrench the vision and give it long-term stability regardless of the political climate, Estonia legislatively codified the decision to invest 1% of its GDP in IT annually. E-Estonia led to a surge of digital capabilities in the country. The country went on to repeat this early success multiple times with programs such as X-Road and e-Residency. Today, Estonia is considered a global leader in digital government.

Collaborative. Agencies that navigate malleable but highly unpredictable domains require a collaborative approach to strategy. The purpose, similar to the aim of the visionary approach, is to reshape the domain. In the face of a highly dynamic and unpredictable environment, however, it isn’t feasible for an agency to craft and realize a vision on its own.

Instead, the focus should be on orchestrating a public-private ecosystem that relies on a diverse network of partners to experiment with new solutions under changing circumstances. The essence of a collaborative approach is to engage, orchestrate, and evolve. Agencies for which a collaborative approach can work well include public health departments, climate and sustainability offices, and digital government centers.

A collaborative strategy requires a strong strategic center that continuously interacts with a wide variety of partners and providers. To successfully implement a collaborative strategy, procurement regulations should be relaxed so that the agency can collaborate within a constantly evolving ecosystem. Scouting for new partners should be a continuous endeavor. Avoid overly specific task descriptions upfront; instead, allow partners to develop their own innovative approaches to solve problems—and pay them for results rather than fixed activities. To ensure the ecosystem’s vitality, focus on collaboration among participants, for example, with community building and data sharing. Rapid progress in digital platform technologies in recent years has greatly facilitated such endeavors.

A successful example of a collaborative approach can be found in the testing, inspection, and certification (TIC) sector. In many countries, a government agency communicates a clear vision for the supervision of all sorts of things, such as food quality and elevator safety, and captures that vision in detailed testing and inspection protocols. It then accredits a network of TIC companies to execute these protocols so that the government does not need to execute them itself. This allows for much more scale and flexibility in delivery. New testing and inspection needs arise constantly and unpredictably as companies design new products and services that require supervision and because new areas of regulation, such as cybersecurity and sustainability, emerge.

TIC companies play a key role in addressing these needs quickly by developing new approaches (often to sell certificates that are not yet legally required but may help their customers signal their trustworthiness to the market). New approaches that work well may eventually funnel back into the testing and inspection protocols. This collaborative approach to supervision has often worked much more successfully than a classical approach. Many data privacy authorities, for example, are struggling to achieve effective oversight because they primarily rely on their own organizations for execution.

Regenerative. Agencies that face an especially harsh environment with restricted resources should adopt a regenerative approach to strategy. When the external circumstances are so challenging that your current way of operating cannot be sustained, decisively changing course is necessary not only to survive but also to secure another chance at thriving. Decisive change often requires scaling down the services and activities to the core, economizing to free up budget, and then investing in key initiatives to future-proof the organization—for example, by transitioning to digital service delivery. The essence of the approach is to react, economize, and reinvest. Elder-care institutions, which face financial strain in the light of an aging population and lengthening lifespans, are one type of agency that may find a regenerative strategy effective. More broadly, this approach applies to any agency that has faced significant budget cuts or declining relevance and clout.

A regenerative strategy requires decisive and hierarchical leadership. It is essential to respond swiftly to triggers because an agency operating above its budget will find it harder and harder over time to find funds for strategic investments. When looking to cut costs, act on three levels: scrutinize internal operations for efficiency, making use of the creativity and knowledge of employees throughout the organization; adjust the portfolio of operations by downsizing to the core activities; and work with external partners such as suppliers to identify cost-saving opportunities for them and translate those findings into renegotiated contracts.

While cost cutting is important, it should not be the sole focus: remain alert to opportunities to invest in the long-term robustness of the agency. Denmark, Singapore, and Malaysia recognized, for example, that investing in digitization programs for public service was essential to improve long-term effectiveness as well as cost-efficiency.

Lastly, proactively engage in a continuous dialogue with political leadership on the consequences and risks of budget cuts. Restoring budget should not be a goal in and of itself in all cases—there are limited fiscal resources that require regular redistribution across agencies to reflect new developments and political priorities—but it is important to communicate the consequences of cost cuts to political leadership when co-creating a strategy with a regenerative focus.

THE APPROACHES AT WORK

Exhibit 2 summarizes the ways to implement the various approaches. Note that within an agency, multiple approaches may need to co-exist, given that different teams or departments operate in different environments. This can lead to significant organizational challenges and require that rules, structures, and processes within those teams be differentiated. Further, environments can change rapidly, so continuous vigilance is required to ensure that a particular strategic approach remains appropriate for an agency and its departments.

Using Strategy to Bridge the Gap Between Policy and Implementation

For each of the five strategic approaches—classical, adaptive, visionary, collaborative, and regenerative—success depends not only on the ability to choose the right approach but also on entrenching it in everyday practices, processes, and behaviors. Ultimately, what matters is not the wisdom of the strategy but the consequences of its implementation.

Good strategy is both extrospective and introspective. On the one hand, it is a method to understand your environment and determine how to change its course; in a public-sector context, this is often referred to as policymaking. The extrospective aspect of strategy is closely intertwined with the political process, as the political agenda is a key premise for setting objectives. On the other hand, good strategy is also introspective: it recognizes that the agency responsible for execution is not a black box but a complex system with distinct strengths and weaknesses, which can be remolded. Designing the organization so that it can execute on a policy is called

The execution gap is a thorny, well-documented problem in strategy.

The execution gap—the difference between strategic objectives that are defined and those that are successfully implemented and achieved—is a thorny, well-documented problem in strategy. Typical solutions focus on either the extrospective side (how objectives are set) or the introspective side (how the organization is set up for execution). For example, while setting objectives, the execution gap can be addressed by committing visibly and collectively to a clear organizational identity and purpose around which you streamline a portfolio of

Yet to diagnose the execution gap as either a failure of policymaking or a failure of implementation misses a crucial point: the criticality of the interaction between the two. A very common feature of government is the separation of those who make policy from those who implement it. As a result, the extrospective and introspective parts of strategy adhere to different cycles and are formulated by different people through different processes. There is usually some cross-pollination, but the level of interaction is often insufficient to create true and ongoing alignment.

This incongruence between the extrospective and introspective parts of strategy is much less of a problem in the private sector. Indeed, empirical studies find that the execution gap is significantly and consistently larger in government than in companies. Large-scale surveys found that 47% of private-sector managers believe that their organization is good at implementing strategy, while only 21% of public managers believe the

Why Are Policymaking and Implementation Disconnected in Government?

Why Are Policymaking and Implementation Disconnected in Government?

In his landmark essay “The Study of Administration,” Wilson introduced the politics-administration dichotomy, which says that civil servants should steer clear of politics and policy, and politicians should not concern themselves with implementation.

Weber, in his magnum opus Economy and Society, argued that public administration should be guided by bureaucratic principles such as specialization, expertise, hierarchy, formal procedures, impersonality, and meritocracy. These principles allow a government agency to scale up while preserving values such as competence, accountability, and integrity. However, these bureaucratic principles are strictly introspective and pay no attention to the environment of the agency. Furthermore, the principles prescribe how an agency should be organized but say nothing about what objectives it should seek to achieve. In Weber’s view, the latter should be the strict prerogative of politicians.

Despite the rising popularity of strategy in recent decades, policymaking and implementation remain disconnected. The idea of strategy has been introduced separately into the spheres of policymaking and implementation, with vastly different contexts, objectives, and practices, and it has since developed in separate directions:22

- The Roots of Extrospective Strategy. The roots of extrospective strategy (policymaking) are in national planning. During the first half of the 20th century, a shift took place toward more coherent programs of government action, which were typically called policies or plans. National plans grew famously popular in Communist countries, such as the Soviet Union and China, but they also very much flourished in their capitalist counterparts. France, for example, started its first National Plan in 1947 and continued with new installments for decades. The US saw a variety of grand plans, such as the Marshall Plan and Johnson’s Great Society. Planning went out of vogue during the turbulence of the 1980s, and the fall of the Soviet Union is often regarded as the death of planning. But extrospective strategy survived in various forms. Today’s government ministries develop an array of extrospective strategies—which they may call plans, policies, strategies, or agendas—for all sorts of domains: from youth crime to cybersecurity, and from

innovation hubs to urban design. Grand national strategy, for example toachieve economic growth or to decarbonize the country, is also used to great effect in many places, such as Singapore, Saudi Arabia, and the European Union. - The Roots of Introspective Strategy. In the face of the financial crises of the 1980s, there was a growing sentiment that many public agencies were fat, slow, and inefficient and should be made more “business like.” Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan first put this idea into practice. They championed a sweeping wave of “managerialization” in the public sector, and countries all over the world soon followed. This managerialization was characterized by the introduction of many new tools and ideas, such as the centralization of power, viewing citizens as customers, performance management, KPIs, incentives, rigorous planning, budget discipline, internal competition—and strategy. The ideas of New Public Management, as the paradigm soon came to be known, were based on a principal-agent view of organizations: Employees did only what their superiors required of them and would shirk responsibility wherever and whenever they could. In this paradigm, strategy is understood to be a managerial tool. It functions as a contract between the leadership of an agency and its various teams, and this contract stipulates what should be delivered, by when, and at what cost. Employees are held accountable for the output they deliver but bear no responsibility for the outcomes. When conceptualized in this way, strategy is useful to manage the cost-efficiency of civil service, but not its effectiveness in creating public value.

To unlock the full potential of strategy, public-sector leaders should abandon the idea that policymaking and implementation must—or even can—be separated and instead commit to a more holistic approach. Strategy can serve as a bridge between policy and implementation. The aspiration is to co-create holistic strategy that balances policy objectives and executive capabilities—and continuously rebalances them in a dynamic environment. When policymaking and implementation mutually reinforce each other, modern strategy provides an excellent tool to diminish the execution gap. In the words of Jenny Stewart, an honorary professor of public policy at the University of New South Wales, “Potentially, the idea of strategy can productively politicize the managerial, and managerialise the

We do not claim that the execution gap can be fully explained as a broken interaction between policymaking and implementation—other causes, such as political pressures to overpromise or a lack of funding, may also play a role. But good strategy has the potential to resolve such discrepancies by providing an explicit space for their collision and harmonization. It puts the differences between the policymaking and implementation perspectives on the table early, rather than waiting for them to materialize down the road.

The disconnect between policymaking and implementation creates myriad problems:

- Civil servants resort to deploying “tactics of control.” In the absence of an explicit space for discussing the executive implications of policy, civil servants have little choice but to resort to tactics of control to manage their own accountability. In extreme cases, the civil service protects itself by keeping elected officials in the dark or by purposely setting unambitious output objectives.

- Executive expertise does not inform policy. Executive agencies can contribute more to policy than just executive concerns; the men and women in the field are also closest to the citizens and typically have valuable insights into their problems, opinions, and needs. Policymaking is stronger when these insights are incorporated.

- Political dilemmas are left to executive agencies. When policy does not concern itself with implementation and vice versa, many of the tactical choices that need to be made rapidly will lack political guidance. But details can matter greatly. Citizens deal not with the idea that was originally conceived in the mind of the politician or policy advisors but with the actual tools and services that spring from it. Many political tradeoffs and dilemmas emerge only in the implementation phase: For example, do we prioritize the speed of the operation or the attention to details? Do we opt for a consistent treatment of citizens or create room to address individual needs?

- Executive agencies and policymakers think on different timescales. Politicians typically seek to achieve results before the next election cycle, whereas civil servants often remain with an agency for years or even decades. This means these two groups are incentivized to think and act on different timescales. While strategy does not take this divergence of incentives away, it does force the different perspectives to collide and harmonize.

What does it take to put holistic strategy across policy and implementation into practice? There is no silver bullet, but in our experience a number of interventions can help:

- Synchronize the strategy cycle with the political cycle. The start of an elected official’s tenure naturally invites political and strategic reorientation, as this person will be eager to make her or his mark. To ensure a holistic approach, executive agencies should synchronize their strategic cycles with the political calendar when possible.

- Ensure that the strategy and budgeting processes are linked. Strategy is worth only as much as the changes it effects. The proof of the pudding is in the budget and the outcomes. To ensure the necessary level of participation on both the policy and executive sides, changes in strategy need to have direct implications for budget allocations and impact metrics.

- Involve executive agencies in setting political agendas. In many countries, important policy decisions are made during political negotiations—for example, while building a coalition of parties that will form the new cabinet after elections. Senior civil servants of executive agencies should have a seat at the table, or at least a role in the process, so that they can voice concerns and provide expert input.

- Think big, start small, scale fast . When designing holistic strategy, it is tempting to address big problems with big solutions—but this often proves ineffective. It is indeed important to think broadly about the challenges that a government faces and the coherent set of solutions needed to address them. But agencies cannot execute on grand programs of action without first developing the enabling competencies that are conditional to success. And while political priorities may shift rapidly, implementation cannot. Good holistic strategy is selective and disciplined: It starts with a small number of key catalytic initiatives that take into account the organizational constraints of the executive agency. Over time, the agency can invest in the acquisition and development of new competencies that fit its strategic approach (that is, competencies to plan, adapt, envision, collaborate, or regenerate) so that the agency can gradually expand its organizational constraints and scale up its solutions.

Creating the Strategic State

How do you move toward a new approach to strategy that is aligned with the needs of your environment while bridging policy and implementation? The specific steps toward improving your approach to strategy are not universal but require a close look at the starting point of your organization. As chess grandmaster Max Euwe said, “Strategy requires thought, tactics require observation.”

What is clear, however, is that all agencies need a much broader set of capabilities to succeed at strategy today than was necessary to succeed at planning in the past. Senior civil servants should know how to implement each of the five strategic approaches discussed earlier and recognize which one to use in a given scenario. They also need to face organization-related challenges that arise when leading an agency whose departments require different approaches to strategy. Consider a police force: the organized crime unit may require an adaptive approach; the traffic police, a classical approach; and the youth crime department, a collaborative approach.

Governments seeking to step up their game in strategy need to enable their agencies to succeed with different strategic approaches. That could mean, for example, that civil service rules need to be rewritten to allow certain agencies more flexibility and room for experimentation while others should stay focused on consistency of outputs. It should also be reflected in training programs and HR decisions, where experience with various strategic approaches becomes a key metric in the promotion and placement of senior civil servants—in addition to their domain expertise.

Finally, elected officials in strategic states need to understand that there is no longer a one-size-fits-all playbook for directing agencies in their portfolio. They need to cooperate with each agency to craft holistic strategy tailored to its environment.

The word strategy stems from the Greek words stratos (army) and agos (leader), which together mean “generalship of the army”—thus, the concept of strategy originated in a public sector organization. For centuries, the notion of strategy played no significant role in government, but the paradigm of the strategic state is gradually reviving its use. It is time for governments to advance to the next stage: learning how to deploy new strategic approaches beyond planning, choosing the right strategic approaches based on the requisites of the environment, and using holistic strategy to bridge the gap between policymaking and implementation.