In the past few years, sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) have become more active in Africa than ever before. Governments have opened up to the idea of establishing their own investment arms to fill critical gaps in financing projects and trigger increased investment in priority sectors.

Development finance institutions (DFIs), funded by national governments and multilateral organizations, are central to attracting investment by providing inexpensive equity and debt. SWFs are more like a hybrid between DFIs and private equity funds and are focused both on gaining returns and on investing for strategic development and impact.

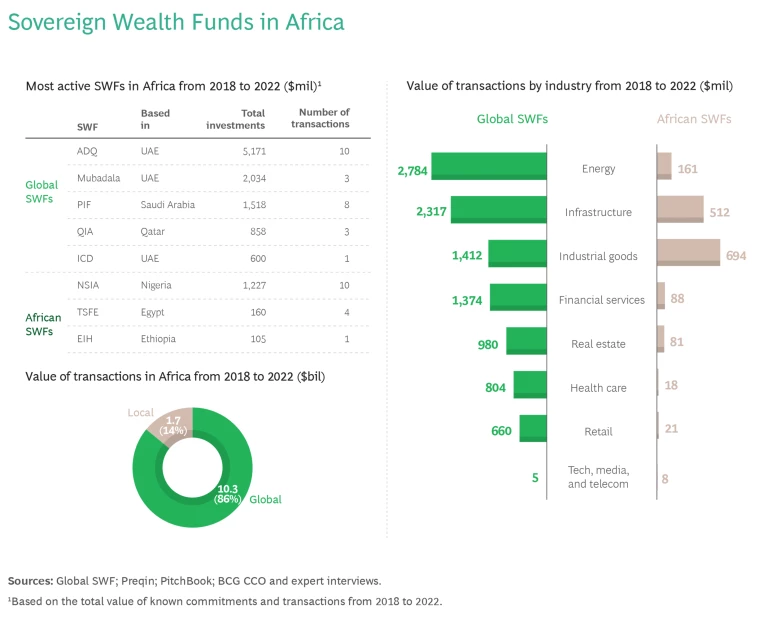

Traditionally, most SWF investments in Africa have come from Middle Eastern funds, but the recent emergence of local African SWFs offers the potential to both shape and accelerate the investment environment. There are approximately 25 state-owned investment funds on the African continent that can be categorized as SWFs. These domestic funds have a unique role to play in the development of their home economies, as well as in attracting capital from international investors.

African SWFs are not as strongly capitalized as the Middle Eastern SWFs that have been active in Africa, nor do they have big government surpluses to tap into. The average ticket size for African SWF transactions over the past few years was $84 million, compared with $383 million for Middle Eastern SWF activity in Africa.

The largest African SWF is Ethiopian Investment Holdings (EIH), which launched in 2022 with $45 billion worth of state-owned assets and is seeking partnerships with foreign direct investors to fuel the expansion of the private sector. The Nigeria Sovereign Investment Authority (NSIA) is the most active fund, with ten known transactions between 2018 and 2022. (See Exhibit 1.)

The Sovereign Fund of Egypt (TSFE), formed in December 2018, is working closely alongside the Public Investment Fund (PIF) of Saudi Arabia and Abu Dhabi Developmental Holding Company (ADQ) to stimulate private investment in a wide range of essential industries and unlock value in state-owned assets. Morocco’s Mohammed VI Fund for Investment (M6FI) with $1.5 billion in equity will be operating largely as a fund of funds, with a plan to allocate $5 billion from investment partners to a series of thematic portfolios that support the growth of strategic sectors, including infrastructure and small- to mid-sized businesses with high potential. Mozambique and Kenya are among the countries that have recently drafted bills for the creation of new SWFs. These funds are well suited to help unlock and contribute to the unique growth opportunities in Africa—which, while abundant, require innovative approaches to capital deployment.

SWFs tend to have long-term horizons and offer flexible structures, with less pressure around exit strategies than there is with other private investors. While the focus of these funds has historically been on government-led opportunities and partnerships, SWFs are now being expanded to include working with private sector players. At the same time, since these funds are backed largely by public money, the cost of capital is relatively low, which makes SWFs ideal investors or co-investors for many of the nascent opportunities in Africa.

While part of an SWF’s investment strategy might be determined by government policy initiatives, the success of any SWF is driven by the financial performance of its portfolio in the long run. This is a major challenge that African SWFs face as they develop their investment thesis and seek additional capital: in order to have the impact that we believe these emerging SWFs are capable of, funds must have the autonomy and ability to manage risks and maximize returns.

In order to have the impact that emerging SWFs are capable of, funds must have the autonomy and ability to manage risks and maximize returns.

In this article, we offer a roadmap that draws on the experiences of other emerging market SWFs over the past decade. A plan for success begins with an evaluation of which industries the fund is in a position to support, which companies or projects within those industries show the most promise, and which partnership structures might be best for a long-term investment commitment and sustainable effect.

Funding Transformation

Investment capital is in high demand across Africa, especially in the infrastructure, energy , and health care sectors, where there is a combined annual financing gap of $300 billion to $350 billion. Many governments have limited ability to address these gaps because they are already highly indebted, while domestic capital markets and banking systems generally lack the critical mass of issuers and products to meet the need for capital. Development finance and donor funding have partially bridged the gap, but more funds are required.

Africa is facing multiple challenges to development, including rapid population growth, widespread poverty, climate change, and low agricultural productivity. Yet its fundamentals remain solid. GDP is expected to grow by 4.3% annually through 2027—a third more than the global average and far surpassing the outlook for Europe (1.5%) and the Americas (1.8%). There are several factors in place that will support growth going forward. Africa has a third of the world’s natural resources and 65% of its uncultivated arable land. There are also untapped renewable energy resources across the continent and a fast-growing urban population.

Behind the fundamentals, several long-term transformative trends are shaping the nature of the investment opportunities on the African continent. Here we look at three of the key areas in which SWFs can play a critical role: renewables and sustainable energy , local value-added production, and infrastructure growth.

Renewables and Sustainable Energy. Fossil fuel-driven climate change is threatening Africa, but the transition to renewables and sustainable, reliable energy is happening quickly. The energy transition is set to unlock a range of investment opportunities across the continent, including in grid infrastructure, gas-to-power, renewables, and green hydrogen. These energy alternatives present a wide range of opportunities to develop a highly competitive sector that can have a powerful impact on local economies.

Local Value-Added Production. Developments in the trade landscape, including new free-trade agreements, import substitution, and industrialization—not to mention the impact of supply chain disruptions during the COVID-19 crisis—have led African countries to try to localize critical production and increasingly move away from the export of raw materials toward more local value-added production. In that respect, project structuring and investments are needed to develop value-added output in a wide range of sectors, including pharmaceuticals, agricultural processing, and electric vehicle manufacturing.

Infrastructure Growth. Large transcontinental projects have the potential to drive infrastructure growth in Africa across countries and transport modes. SWFs are participants in a number of Africa’s most high-profile infrastructure projects, including railways and ports in East Africa and the Trans-West African Coastal Highway that links 12 coastal nations.

In the past several years we have seen African SWFs step in to fill the funding gaps and establish themselves as stakeholders in these transformative areas, using a variety of transaction structures. For many newly established African SWFs there is a clear focus on leveraging existing state-owned assets, often using private sector capital. Others, however, are playing a more active role in nation building and local economic development. We have also seen a number of partnerships with Middle Eastern SWFs that have an interest in Africa’s growth opportunities.

In Egypt, for example, TSFE has established a $20 billion dedicated investment vehicle in partnership with Abu Dhabi’s ADQ. The TSFE and ADQ platform favors investments that link to one another in related businesses. It is designed to help advance Egypt’s economic development in health care, pharmaceuticals, utilities, food and agriculture , real estate, and financial services .

In Nigeria, the NSIA has funded various domestic infrastructure projects. For example, it has invested $440 million in the construction of a 1.6 kilometer-long bridge in Niger, along with a series of secondary bridges and connecting roads. The undertaking is designed to relieve congestion on the existing bridge between southeastern and southwestern regions of the country and boost economic activity. The NSIA is also a participating investor in an $808 million project to build a 127 kilometer-long expressway connecting Ibadan, the capital of Oyo State, to Lagos.

SWF managers are looking at opportunities to acquire stakes in African companies in target sectors or to buy them out fully. In 2021, TSFE and ADQ acquired Amoun Pharmaceutical Company, a leading Egyptian life sciences enterprise, for $740 million through a joint investment platform.

Some African SWFs are investing in projects that include neighboring countries and are intended to stimulate development throughout the region. EIH, for example, has invested $105 million for a 30% stake in the Damerjog Liquid Bulk Port, a logistics port facility located in a rural village in neighboring Djibouti, and plans to partner with investors there. The investment is aimed at boosting regional integration to open up more financing opportunities in Ethiopia and beyond.

NSIA is partnering with OCP, Morocco’s state-owned phosphate company, to develop a basic chemicals platform to produce ammonia and phosphate fertilizers. The project is designed to develop a multipurpose industrial platform in Nigeria and advance the country’s sustainable and inclusive agriculture practices.

How SWFs Can Make an Impact

The majority of African SWFs are still in the relatively early stages of development. As they begin to pick up the mantle for nation building, they should take a leading role in identifying opportunities in priority sectors, securing greenfield projects, and attracting capital from international SWFs and other private investors.

As African SWFs begin to pick up the mantle for nation building, they should take a leading role in identifying opportunities and attracting capital.

It is critical, however, that they establish their self-contained role in their country’s economic development up front. SWFs should function as partners to the government but with their own criteria for evaluating investments and their own oversight. The following four measures will help ensure that new SWFs are in a position to make the strongest possible impact:

- SWFs must clearly define their mandate. The purpose and goals of the SWF need to be well-defined and aligned to priority areas of support and development. The fund should be positioned at the center of investment and cooperation discussions and agreements with regional and international investors. The mandate should also be complementary to those of other state investment vehicles, such as pension funds and development banks. All parties should understand the value that the SWF can bring for national development, beyond existing investor and government activity.

Governments must equip their SWFs with the tools to win. It is also important for the nation’s government entities to empower SWFs to execute their mandate by providing them with the necessary capabilities, including capital allocation and organizational capacity. Moreover, as custodians of state-owned assets, SWFs need to assure that the fund and its portfolio companies deploy world-class governance and operating models that guarantee the fund’s integrity and independence. The quality and transparency of the institutional setup will be a key determinant in positioning local SWFs as trusted partners to external investors.

SWFs can take inspiration from the International Forum of Sovereign Wealth Funds Santiago’s Santiago Principles, which promote good governance practices and offer a legal framework, policies, rules, and operational model.

Fund managers must be focused on risk and return. While investment targets may be determined at least in part by the country’s needs, decisions about where and how to invest should be based on the fund management’s due diligence and strict evaluation of the potential for risk-adjusted return.

To that end, it is critical that fund managers set clear investment criteria. Conventional wisdom in the investment world says that a portfolio has room to absorb some degree of loss as long as there are also some strong wins. But with the inherent equity risk in Africa’s emerging markets , SWF managers should define an acceptable minimum expected return for all projects and base their investment decisions accordingly.

SWFs must forge strong partnerships to build an investment ecosystem. African countries often lack the financial resources to capitalize their SWFs that their Middle Eastern and developed country counterparts enjoy. To leverage capital and reach scale, African SWFs need partnerships with other SWFs and DFIs as well as private sector players such as multinational corporations, private equity managers, and institutional investors—with the SWF taking the lead in bringing projects to scale.

An SWF’s involvement in any project should be additive, unlocking opportunities for other investors and industry players that would not have been available. It should also be multiplicative, with the local SWF acting as the coordinator of other private and public investor opportunities, thereby multiplying the impact of its own invested capital.

An SWF’s involvement in any project should be additive, unlocking opportunities for other investors and industry players that would not have been available.

As an early stage SWF begins investing, its managing partners will need to make sure it sticks to its established purpose and objectives and remains rigorous in its selection process. As it reaches maturity, managers must determine optimal exit and reinvestment strategies, expanding the portfolio to establish more synergies and perhaps a broader scope. The funds that identify successful opportunities in Africa and bridge the most critical investment gaps stand to become leaders in building the most vital industries for the 21st century.

The authors wish to thank Omar Baklouti, Johann van Eerden, Laurie Evans, Ketil Gjerstad, and Ihab Khalil for their contributions to this article.