Leading consumer-focused businesses are automating their warehouse networks , generating step changes in service and cost performance. Some companies have already unlocked 20% to 50% improvement in service levels while generating a 25% to 50% reduction in fulfillment costs—all while boosting their resilience amid today’s acute labor shortages.

Despite these success stories, however, many consumer-focused businesses are finding it difficult to make an adequate return or meet their automation design goals in their initial pilot, stopping the project in its tracks. Others have run successful pilots but struggled to scale the technology across their entire warehouse network, and some have been hesitant to restructure their network, preferring to focus directly on warehouse design instead of addressing the broader network strategy. Still others are struggling to create a comprehensive benefits case, making it difficult to gain buy-in across the company.

To overcome these hurdles, businesses should work step by step to understand each of their warehouse archetypes and develop the most critical use cases within those archetypes. They should dig deeply into their existing warehouse operations to amplify ROI before automation begins. And they should fully commit to an agile automation effort—articulating a clear business case at the C-level, establishing a high-performing transformation management office, and finding the right balance between in-house and external support to carry the transformation forward.

The Automation Imperative

Less than a decade ago, large-scale warehouse automation was considered too costly to generate a reasonable ROI, particularly in the face of an ample labor supply and relatively low wages. This perspective has changed markedly due to three factors: advances in both automation and mechanization technologies and intelligent planning and execution software; newfound labor shortages; and an increase in supply chain complexity.

The Growing Labor Gap. Today’s labor shortages stem from a number of issues. Many older warehouse workers are retiring, and younger workers often show little interest in long-term warehouse employment or view warehousing jobs as temporary stops along their career path. Some businesses have even reported annual turnover rates exceeding 100% in their most competitive labor markets. Further widening the growing labor gap, more warehouse employees are required to fulfill labor-intensive e-commerce order demand than were needed in a purely brick-and-mortar retail world.

Naturally, businesses are offering higher pay and new perks to attract the labor they need—but this has not typically been enough. Wages for private industry workers increased 5.1% from 2021 to 2022, according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, while warehouse labor compensation increased 3.5% over the same time period. At the same time, overall distribution center (DC) productivity has remained flat, increasing the cost per unit.

The labor shortage is not just affecting costs. It is also damaging the customer experience through poor service. For example, joint BCG supply-chain surveys with FMI, the food industry association, found that on-time delivery rates to US retailers had dropped from more than 90% pre-COVID to 75% by early 2021—hurting businesses’ ability to grow.

Increasing Supply Chain Complexity. Consumer demand is now much more volatile, particularly since the pandemic began. As a result, retailers continue to insist on more options and assortment sizes, faster order cycles, and other service enhancements—even as product shortages at the manufacturing level have become more common. In fact, our recent work with retailers and manufacturers reveals that the DC order replenishment lead times expected by retailers have gradually been cut to just three to five days, from the traditional seven. The result is tremendous upstream operational complexity.

These issues have given consumer-facing businesses an entirely different perspective on their operations. Without new workers to fill the labor gap, warehouse mechanization and automation have become more and more important in helping DC operators maintain business continuity.

Jumping on the Automation Bandwagon

Most large consumer-focused businesses have already elevated supply-chain investments and performance to the top of their leadership agenda. US Census Bureau data released in December 2022 reveals that spending on commercial construction, which includes warehouses, in the US is about 21% higher than it was a year earlier. Retailers such as Walmart, Kroger, Woolworths, Meijer, H-E-B, and Ahold Delhaize have adopted and implemented new warehouse automation technologies. Across its fulfillment and sort centers and air hubs, Amazon Robotics has deployed more than 520,000 robotic drive units.

The warehouse automation market is expected to reach $41 billion by 2027, with a CAGR of almost 15% between 2020 and 2025. In addition, three-fourths of all large enterprises will have adopted some form of intralogistics smart robots in their warehouse operations by 2026, according to Gartner, while ABI Research notes that more than 47,000 collaborative robots will be shipped to warehouses over the same time period. Meanwhile, demand for robotic “goods-to-person” systems—in which products are delivered directly to a warehouse operator via automated systems—is expected to increase fourfold.

The rising demand for automation is generating rapid acceleration in innovation. Venture and private equity funding for warehouse automation solutions such as conveyors, turnkey solutions, autonomous warehouse robots, automated guide vehicles, and cube-based storage and retrieval systems is increasing steadily, as is funding for supply-chain technology such as warehouse management systems, execution software, and control systems.

And system integrators and technology solution providers are rapidly integrating such innovations into their automation-solution hardware and software. In a span of just three to five years, for example, the installation of high SKU-density micro-fulfillment facilities powered by robots has expanded to more than 1,000 customer sites globally.

Mixed Automation Success

Despite the growing level of investment, only perhaps a tenth of the companies hoping to scale automation technologies across their warehouse operations have found sustained large-scale success.

Many automation efforts have been unable to reach their stated design mandates and ROI goals during the initial pilot, making it difficult to justify scaling. Supply-chain leaders may have chosen an exciting new technology, for example, without considering the full spectrum of available solutions—translating into an interesting test pilot but suboptimal outcomes. Given that hundreds of automation startups have appeared in recent years, offering a flurry of indistinguishable alternatives, it is perhaps no wonder.

Still others have been unable to scale, despite a successful pilot, due to difficulty in assessing the implications for different warehouse types, understanding how the automation design should address future requirements, or seeing how automation fits into the broad canvas of their distribution network operations—both upstream and downstream.

In addition, some have made changes only within their individual warehouses rather than addressing the broader network strategy, greatly limiting their success. And finally, some teams have been unable to engage with adjacent functions effectively, such as merchandising, sales, transportation, and store operations—and build a comprehensive benefits case. As a result, they are unable to gain complete buy-in and end up limiting the initiative to a supply-chain-only effort.

Three Inspirations for Automation at Scale

Designing and scaling the automation of a warehouse network is an inherently complex task. In our experience, companies have been able to overcome this complexity by:

- Establishing the most relevant use cases for automation within the businesses’ different warehouse archetypes.

- Amplifying existing ROI potential before beginning to automate.

- Running a comprehensive and agile automation effort.

Establish Anchor Use Cases

To successfully automate at scale, businesses require a compelling and actionable business case that can justify the multiyear transformation effort and overcome any ROI hurdles. They should therefore begin by identifying the optimal uses for warehouse automation—uses that will address critical, labor-intensive processes within each warehouse.

This process means first categorizing all of the warehouses in the network by their operations archetype. Automation is not a one-size-fits-all endeavor and should be tailored to the complex array of product flows and fulfillment requirements of each type of operation. (See the slideshow, “Four Steps to Tailoring Warehouse Animation.”)

In our experience, there can be more than a dozen archetypes, depending on the role that each warehouse plays in the network. For example, a “flow” DC has minimal storage requirements, as it predominantly helps with cross docking and the consolidation of shipments within the network. In contrast, a “stocking” DC primarily holds inventory and directly serves different demand types, whether it ships to customer DCs or retail stores, or fulfills consumer orders directly. It is also common for warehouses to contain multiple archetypes under a single roof or a campus, further stressing the need for this upfront categorization.

The next step is to create a clear baseline of the costs, labor intensity, capabilities, and technology solutions needed to support the current and future business needs of each of the designated archetypes. In addition, businesses should map out the pain points and opportunities associated with each warehouse activity—including unloading, receiving, put-away, picking, packing, sorting, or loading—within these archetypes. This will help them to understand and delineate the most practical, value-generating uses of warehouse automation technology within their unique warehouse configurations.

Businesses can then:

- Collaboratively engage technology providers on the solutions they have to offer through a well-thought-out and comprehensive RFP, inviting providers to share a pro-forma business case across multiple investment scenarios.

- Choose the appropriate solutions and corresponding provider through rigorous vetting, including reference site visits, reference calls, and interviews to assess the provider’s capabilities.

- Jointly build a robust warehouse automation blueprint that links the business requirements to a set of use cases that the business can act on, along with corresponding, purpose-fit software solutions.

Amplify ROI Potential

The cost of automation can be high. As a result, even when companies find optimal use cases, the ROI can be poor, or long-delayed—even as labor costs rise. Nonetheless, companies can find ways to amplify their automation ROI—and more than justify the effort. Here are four moves to explore:

Consolidate Warehouses. Businesses can more easily validate their automation investment by thoughtfully consolidating their warehouse network. One possibility is a hub and spoke model—a centralized distribution system with a few, larger locations acting as “hubs” that carry slower-moving SKUs and many smaller facilities carrying faster-moving consumer products out on the “rim,” closer to the consumer.

Broaden Solution Scope. Finding opportunities for automated solutions in a single distribution center to play multiple roles can boost efficiency and increase returns. For example, an automated picking solution might handle home-delivery batches, store-replenishment orders, and return-sorting activities, managing combined volumes across distinct uses.

Optimize Inventory. Based on our experience, retailers and CPG businesses in particular can generate higher potential automation ROI through improved planning and the reduction of inventory days on hand, particularly in warehouses that are close to the consumer.

Assess Downstream Benefits. While warehouse labor savings, both direct and indirect, constitute a major portion of the benefits created by automation, we also see value in comprehensively assessing and including potential transportation and store-labor efficiencies, especially within retail supply chains.

By amplifying its ROI potential, a fast-moving consumer goods company recently pursued a highly successful multiyear automation effort within its US warehouse network. It began by prioritizing the potential uses of automation across all of its warehouse archetypes and identifying the set of distribution centers that had enough volume and labor intensity to attain internal ROI targets. It then consolidated slower-moving products within just three mega-distribution centers and improved inventory turnover across its remaining, close-to-demand facilities.

As a result, the company was able to shift a significant portion of overall order volume to fewer facilities. It then targeted those facilities for automation, creating a strong business case that ultimately supported a $500 million capex investment with a 40% ROI.

Run an Agile Automation Program

In this final, critical step, companies need to establish and run a comprehensive, agile automation program. While the agile approach is not unique to warehouse transformations, the training, feedback, and iterations of agile will be extremely supportive. The program should be supported by three pillars:

Articulate a C-Level Business Case. Support at the C-suite level is critical to providing a mandate to cross-functional teams, obtaining resource prioritization, and unlocking downstream process changes. But without end-to-end process changes, cross-functional buy-in and sponsorship, and timely capital allocations, the longer-term effort will falter.

Automation strategies often fail to capture C-suite attention because the business case is too focused on a narrow set of benefits, such as cost reduction or greater capacity utilization. Instead, the C-suite often wants to see a more strategic articulation of value, such as how automation will support growth, generate downstream efficiencies, and increase resilience.

One North American beverage company was excited about the growing e-commerce share of its retail and food-service fulfillment, which it expected to exceed 40% by 2030 and wanted to support this growth through automation. At the same time, the project leader knew that service requirements and costs would increase significantly with e-commerce growth, making it difficult to justify the business case for automation based solely on cost savings.

Instead, the project leader compared a conventional and an automated network by assuming that labor wages—which total 60% to 65% of warehouse fulfillment costs (excluding shipping)—would continue increasing and that productivity would be affected by rising labor turnover. They were then able to calculate the cost savings from automation along with the working capital savings from consolidating the company’s network. As a result, they were able to postulate a more than 50% cash ROI (cash savings to cash costs) from investing in the planned automation. In addition to this financial business case, they were able to articulate the improvements in supply chain performance that would result, including enhancements in speed and fulfillment.

Ultimately, the business case was well received by the board and $1 billion of capital was approved to restructure the network, enabling step changes in channel growth.

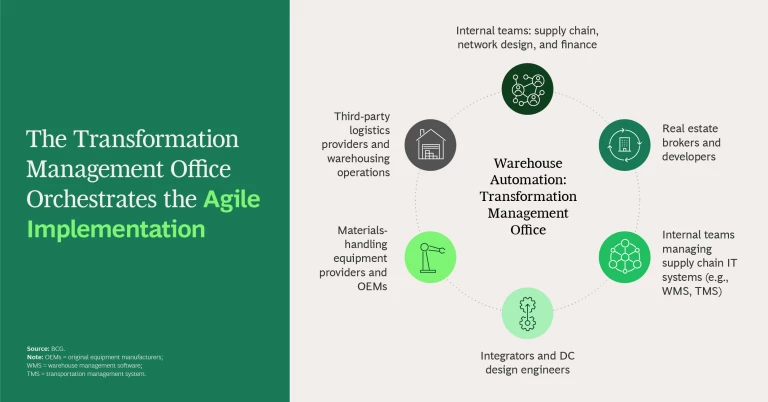

Set Up a Transformation Management Office. The transformation must become a critical strategic program for the company and a key part of the overall business agenda. As a result, the business should establish a TMO to support the transformation that is directly sponsored by a member of the executive leadership team and led by a full-time supply chain leader who is responsible for the delivery of the program’s value and for meeting its timeline. This leader should track milestones at the level of the individual workstream, engage closely with external providers, and ensure that there is sufficient leadership attention as well as the day-to-day resources to move the work forward at a steady pace.

The TMO should also include:

- Dedicated finance personnel who can validate the impact figures and track the benefits and progress of automation through the P&L.

- HR support to manage any implications for and communications with employees.

- Software integrators and engineers to manage integration builds, technical architecture design, platform analytics, and training, and continuous deployment. (See the exhibit.)

Orchestrate Internal Functions and Third Parties

As they set up their TMO and prepare to begin the implementation, companies need to find the right balance between relying on external parties and managing the work themselves. It may be tempting to rely heavily on third parties to design and manage the program, for example, but it is better to gradually build this muscle in-house where possible. Companies should therefore clearly articulate the functions, roles, and resources required to deliver all projects and activities early on, then thoroughly review in-house versus external support for each role.

Further, they should engage a blend of different providers during the RFP process, including automation OEMs, end-to-end integrators, and warehouse-design specialists. This will help the leadership team choose the partnership model that best complements in-house capabilities.

The extent of potential outsourcing will vary with the business’s automation maturity. While most businesses will be able to rely on in-house staff for the IT and operations components of the transformation, companies that have not yet begun automating will necessarily lean on external providers as they begin to build their in-house expertise.

In addition, companies should be sure to bring an appropriate mix of technical experts and strategic support into the TMO, aiming for people who will flourish in their roles, challenge assumptions, stay with the effort, and elevate the program as a whole.

As supply chain volatility, labor gaps, and increasing complexity continue to push consumer-focused companies toward automation, it’s imperative that they pause to clearly articulate their unique automation requirements. While warehouse automation presents unprecedented opportunities for companies to scale quickly and generate value, companies need to apply a strategic and comprehensive approach to implementation if they are to generate the best return on their investment.