For some startups and other potential target companies, there may never be a better time to entertain merger proposals from special-purpose acquisition companies (SPACs). SPACs are listed shell companies that exist solely to merge with private companies and thereby take them public. In some cases, using a SPAC to go public is a viable alternative to a traditional IPO or a direct listing.

SPACs experienced a phenomenal rise and fall in 2020 and early 2021. The frenzy fizzled out because of intensified regulatory scrutiny and changing market dynamics. However, many SPACs launched during the boom are still looking for targets to merge with. At the end of 2022, approximately 350 SPACs (with $96 billion in raised proceeds) faced a 2023 deadline to acquire a target—and most of them must make a deal during the first quarter.

With so many SPACs under pressure to hook up, potential targets have an opportunity to strike favorable deals that overcome the pitfalls of such mergers . To navigate their discussions with SPACs, targets first need to understand how these vehicles work. They should then conduct an in-depth analysis to evaluate individual SPAC suitors and prepare to negotiate from a position of strength.

The Phenomenal Rise and Fall of SPACs

SPACs enter the market via an IPO (a “SPAC IPO”) and usually have a two-year window within which to complete a reverse merger with a target (a “SPAC merger” or “de-SPAC transaction”). Extensions of this deadline are possible if negotiations with a target are underway. A SPAC that fails to meet the merger deadline must give its investors their money back, plus interest.

For many years, SPACs were considered a niche investment vehicle in capital markets. That started to change in 2017, when the number of SPAC IPOs and mergers began trending upward. Then, equity markets’ recovery from the initial shock of the COVID-19 pandemic triggered a frenzy of SPAC activity from mid-2020 through the first quarter of 2021. SPACs raised record proceeds via their public offerings, while major players with diverse backgrounds got into the game as sponsors and investors.

The surge in activity was extraordinary. The proceeds from SPAC IPOs in the first quarter of 2021 exceeded those in the entirety of 2020. For all of 2021, SPAC IPO proceeds accounted for 39% of the global IPO market. SPACs used the proceeds to merge with high-profile startups, including DraftKings, Grab, Lucid, Polestar, and WeWork. These transactions provided SPAC sponsors and investors with enormous returns.

But the SPAC boom led to greater regulatory scrutiny. As the frenzy was peaking in 2021, the US Securities and Exchange Commission proposed stricter rules covering forward-looking statements and accounting and disclosure. In March 2022, the SEC proposed additional rules covering disclosures by sponsors, liabilities of financial advisors and underwriters, disclosures related to the fairness of transactions, and the use of projections, among other topics. The proposed changes would eliminate some of the advantages of going public via a SPAC versus a traditional IPO.

The prospect of tighter regulations contributed to a sharp decrease in the number of new SPAC IPOs and diminished the market’s enthusiasm for SPAC mergers. Indeed, in recent quarters, the number of SPAC IPOs and mergers has reverted to preboom levels. Funding from public and private investors has plunged, while redemptions by existing investors have increased sharply. Exhibit 1 shows the phenomenal rise and fall of SPACs across several indicators.

Subscribe to our M&A, Transactions, and PMI E-Alert.

Many SPACs Face an Imminent Deadline to Merge

Recognizing the constraints in the current market environment and the impracticality of meeting their merger deadline, some SPACs have liquidated and returned proceeds to their investors. But others have not given up. In fact, as noted, the first quarter of 2023 could see a burst of activity. SPACs that had IPOs during the frenzy of the first quarter of 2021 are nearing their two-year deadline for finding a target. In April of this year, the number of SPACs approaching that deadline will decline sharply and continue to fall.

The current market environment gives target companies a window within which to apply strong bargaining power to negotiate more favorable terms than SPAC sponsors have traditionally offered. We have already observed this in recently announced SPAC mergers. To make a deal, some sponsors have been willing to surrender some of their upside opportunities and downside protections. Moreover, the window may close quickly as the number of SPACs hunting for targets decreases in the second quarter.

Indeed, despite the regulatory and market challenges faced by SPACs, potential target companies should still view them as viable vehicles for going public. For example, an important advantage over traditional IPOs is that the target’s valuation and final price are set in negotiations with the SPAC rather than by the market or an IPO book-building process. This makes going public via a SPAC merger less susceptible to market volatility than the traditional IPO route. It also can be a faster route to going public, especially considering that market conditions will likely remain unfavorable for IPOs in the near term. Additionally, a SPAC merger provides access to capital and, possibly, management or industry expertise. These benefits may be relevant to young private companies seeking to go public, as well as to private equity funds that want to exit portfolio companies.

Before testing the waters, however, potential targets should evaluate the downsides of a SPAC merger. For example, in the aftermath of the recent frenzy, many investors have a negative view of SPAC transactions. Management teams should also consider the associated costs, as well as the additional burdens of working with the SPAC’s sponsor and management team in the postmerger organization. Given the pros and cons, it’s likely that only a select few companies will be the right fit for a SPAC deal.

For private companies that are good candidates for a SPAC merger, preparing to negotiate a favorable deal begins with understanding how this investment vehicle is structured.

Understanding SPACs Across their Life Cycle

There are four main players in the SPAC life cycle: the SPAC (its sponsor and management), public investors in the SPAC, institutional investors invited to buy shares through “private investment in public equity” (PIPE), and private companies that are potential targets.

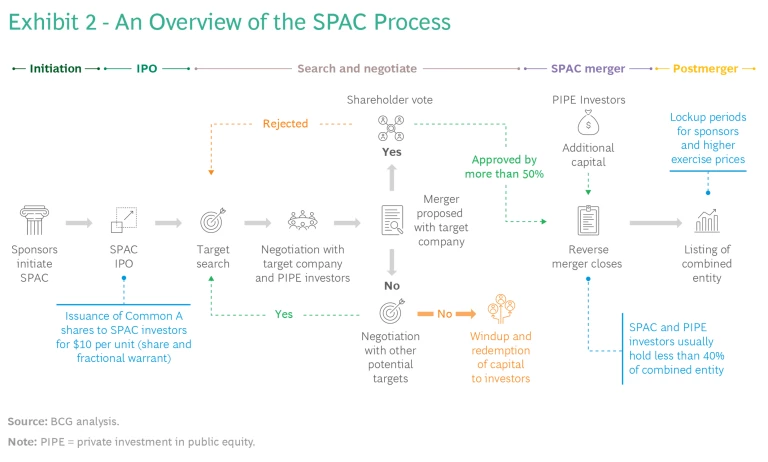

The SPAC life cycle comprises five stages. (See Exhibit 2.)

Initiation. The SPAC sponsor initiates the process by developing an investment thesis and forming a management team. Team members may have backgrounds in a specific industry (for example, former Fortune 500 executives) or capital markets (investment bankers or private equity professionals). The team sets up the legal entity, provides financing for upfront expenses, and prepares for the shell company’s IPO and a road show to attract investors.

The SPAC IPO. Because the shell company does not operate a business, taking it public takes less time than a typical IPO. The IPO proceeds are held in a trust account until the SPAC merges with a target company.

There are two classes of investors: public investors and the sponsor. Public investors receive ownership units composed of shares and warrants that entitle them to buy more shares later at a predetermined price. Each ownership unit is initially valued at $10. Until a reverse merger occurs, public investors hold 100% of the company’s value and are permitted to trade their shares and warrants separately. The sponsors, in exchange for initiating and funding the SPAC and running its operations, get a stake called the “promote.” If and when a reverse merger closes, the sponsor can convert the promote into a large share of the SPAC—usually around 20%—which then becomes a stake in the combined company. The disproportionate ownership share gives the sponsor a higher payoff at the time of the merger.

Search and Negotiation. SPACs typically merge with a single target that is several times the size of their IPO proceeds. As noted, they usually need to merge within two years of their IPO. Many SPACs are looking for young, technology-driven companies with huge growth prospects, but they are also open to other sectors and business models. Applying the sponsor’s investment thesis, the SPAC identifies and contacts potential targets and, if the management of one of them is interested, initiates negotiations. Targets can also reach out to SPACs proactively. If the process advances to a letter of intent, the parties negotiate a merger agreement. The SPAC often concurrently pursues PIPE financing. Until the merger closes, SPAC investors have the right to redeem shares and get back their invested capital.

Merger or Wind-down. The process for the merger of the SPAC and target is, loosely speaking, similar to a funding round. The parties negotiate a price for the target company, and, at the closing, the target’s shareholders receive shares in the SPAC on the basis of this price. In addition, PIPE investors can contribute capital in exchange for shares in the newly combined entity. The combined entity usually bears the costs of the transaction. Alternatively, if a SPAC does not merge with a target within two years, it must wind down by repaying its investors.

Postmerger. After the transaction concludes, the combined company is usually renamed and trades with a new exchange ticker. Its shareholders include the investors in the former target company (who are typically still the majority shareholders), investors in the former SPAC, and possibly PIPE investors. Sponsors are subject to lockup periods and higher prices for exercising the promote and warrants.

Imperatives for Navigating Negotiations with SPACs

Companies negotiating a reverse merger with a SPAC can learn from the challenges encountered by targets during the recent SPAC boom. Chief among the lessons is that targets should avoid giving away too much value. With few exceptions, SPACs are structured to disproportionately benefit their sponsors, not the shareholders of the companies they acquire. By following several imperatives, targets can improve their chances of capturing the benefits while avoiding the pitfalls.

Conduct thorough due diligence on the SPAC and its management team. Find out the investment thesis underlying the SPAC’s initiation and IPO, as well as the technical mechanisms for exercising the promote and warrants, especially during the period around the SPAC merger. This information will help you understand the sponsor’s and management team’s perspectives on how merging with your company could create value. You also need a clear understanding of your company’s valuation in order to determine the sweet spot within the range of bargaining positions.

Targets should avoid giving away too much value; by following several imperatives, they can improve their chances of capturing the benefits while avoiding the pitfalls.

In addition, assess the quality of the sponsor and management team with respect to their professional experience and reputation. Determine whether the management team is composed of industry specialists or generalists. This is important for assessing whether the SPAC’s team will fit well with your current management team. Industry specialists have experience in corporate management functions, including investor relations. Generalists have backgrounds in capital markets—including track records in raising capital, building an investor network, and communicating with investors. Experience with fundraising in capital markets is especially valuable if your company plans to continue seeking large amounts of capital.

Align incentives and take a long-term view. The sponsor’s continued involvement in the combined company can be beneficial for subsequent efforts to raise capital. That makes it important to align the sponsor’s incentives with your company’s overall strategy. Incentives can be aligned via lockup periods and performance ratchets (the thresholds for exercising warrants or receiving other incentives). Strategies to prolong the sponsor’s commitment include delaying the ability to convert the promote into public shares or reducing the postconversion percentage of ownership. Similarly, the parties can delay the timing or raise the price for exercising warrants.

Although going public via a SPAC will be a significant milestone for your company, it is not the ultimate destination. Take a long-term perspective that goes far beyond the first trading day for the combined company. For example, consider appointing the SPAC’s sponsor and management team to executive positions in the combined company in order to benefit from the SPAC team’s expertise and marketing capabilities to grow the business. Additionally, appointing the sponsor or management team members to the company’s board of directors allows them to influence strategic decisions. This will help broaden their focus from short-term returns to a longer-term view of value creation.

Make sure you get enough money net of transaction costs. Ensure that the price paid for your company adequately reflects its value, bearing in mind that you will not know in advance how much cash will be transferred from the SPAC. It’s especially important to ensure that the minimum cash committed by the sponsor, together with the PIPE financing, will meet the combined company’s capital needs. The proceeds of the PIPE financing are the only funds from the transaction that the combined company can be certain it will receive when the merger closes. Because the SPAC’s shareholders can redeem shares before the merger’s closing date, the amount of cash that the combined company will receive from the shell company’s IPO proceeds is uncertain until the closing occurs. In assessing the adequacy of the PIPE financing, consider that it will be more complicated to complete large capital raises once the target becomes a public company.

Although going public via a SPAC will be a significant milestone for your company, it is not the ultimate destination.

In addition, gain clarity on the costs associated with the merger. These costs include fees, the dilution of share value for current investors, and the valuation discounts applied by the SPAC in the acquisition price. The combined entity also usually bears the costs of the underwriting process; for example, payment for two-thirds of the SPAC IPO’s costs is typically deferred until after the merger. Taken together, such costs may mean that a SPAC merger is not a less expensive route to going public than an IPO. Consider ways to reduce costs; for example, increasing the PIPE financing can mitigate the dilution caused by the sponsor’s promote.

Manage the expectations of existing investors and new shareholders. Explain to your existing investors why you believe that going public via a SPAC merger is the right strategy for the company. After the merger, these private investors will become public shareholders, along with the SPAC’s sponsors and shareholders and new investors from the public and private markets (both institutional and retail). The combined company’s investor relations strategy will need to address the concerns of all market participants, such as through the frequency of reporting and the depth of results and forecasts.

Prepare for postmerger operations. Before the closing, establish the internal structures and processes required to operate as a public company. The target company’s management team, especially the CFO, is responsible for ensuring that processes for controlling, reporting, regulatory filings, and investor relations, as well as IT systems, are ready for regulatory review and meet the standards for public companies. This can be a daunting challenge for the management team, which must simultaneously prepare for the closing and run day-to-day operations.

Get ready to counter a disappointing postmerger stock performance. Be prepared to handle the postmerger pressures of leading a publicly listed company that continually changes in value, in contrast to only sporadic valuation changes during funding rounds. Expect the initial performance to be disappointing. As noted, ownership units in a SPAC are typically valued at $10 for the IPO. After the merger, especially in today’s postfrenzy environment, the combined company’s share price will likely be less than $10. This revaluation reflects public markets’ reassessment of the intrinsic value of the target’s business and the dilution effect of issuing additional shares when the promote and warrants are exercised.

To counteract the postmerger drags on the share price, define a proactive strategy to retain shareholders and attract new investors. Focus investors’ attention on the former SPAC’s current identity as an operating company and on how the company’s business model will create value in the coming years. Communicate a clear and convincing growth and equity story that emphasizes the soundness of growth projections and the quality of your management team.

For private companies that are the right fit for going public via a SPAC merger, the next few months may be the best opportunity to make a favorable deal. However, SPACs are complex investment vehicles that are in many respects designed to favor their sponsors and IPO investors. To capitalize on the advantages of the prevailing seller’s market, targets need to build a strong knowledge base and apply the insights in discussions with SPACs. Preparation and a willingness to negotiate boldly are essential for success.