Up to $250 billion in GDP could be in jeopardy across six Asia-Pacific countries by 2035—not because of the usual suspects (geopolitical conditions or pandemics) but because of a demographic trend whose true implications might not yet be apparent to company leaders. As Asia-Pacific ages, more employees will become caregivers. Some will be dual caregivers, tending to both elders and children. Managing the responsibilities of caregiving and employment requires time, flexibility, and energy, and affects well-being both at home and at work. If employed caregivers don’t get the support they need to be both caregivers and productive members of the workforce, a talent exodus could ensue—costing companies and draining national coffers.

Our latest Diversity and Inclusion Assessment for Leadership survey, conducted in 2022, captured the experiences of some 9,000 employees of midsize to large companies in six Asia-Pacific countries (Australia, China, India, Indonesia, Japan, and Singapore). Our sample was balanced in terms of gender and level of seniority at work. More than half of the employees in our sample identify as caregivers outside of their paid employment: we call this group employee-caregivers to signify their dual responsibilities. Our analysis indicates that the number of employee-caregivers is set to increase dramatically. The statistics paint a picture of a potential caregiving—and economic-—crisis for Asia-Pacific:

- Across the six Asia-Pacific countries studied, the number of employee-caregivers will grow by 100 million to a total of 1.2 billion in 2035.

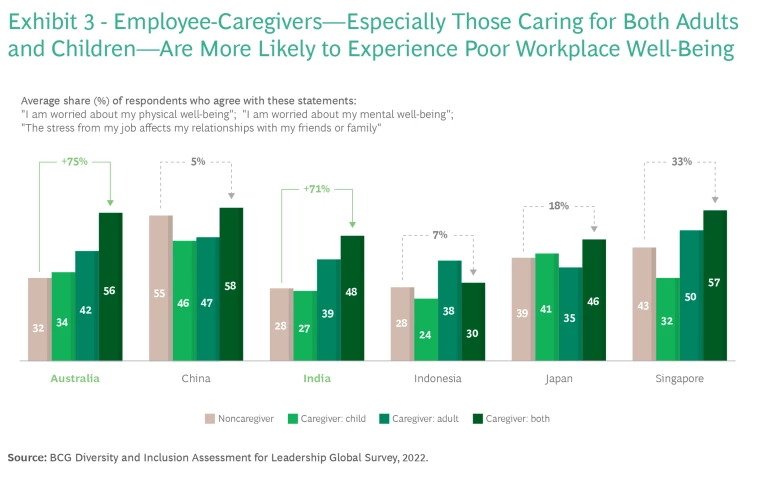

- The employee-caregivers in our survey already report lower feelings of well-being: in some countries, they are 70+% more likely than employees who are not caregivers to say that they are worried about their physical and mental well-being, for instance.

- Absent new support to improve employee-caregivers’ well-being and ability to care for dependents, the labor market in Asia-Pacific could see increased numbers of caregivers leaving the workforce. Our analysis projects that the upcoming exodus of caregivers in the six countries under study could cause a total GDP loss of $125 billion to $250 billion by 2035.

Given this threat, employers should take steps to mitigate an employee-caregiver exodus—particularly given that, as our survey found, many of these employees are notably ambitious. They are ready, willing, and able to bring greater value to their employers—if they can be motivated and retained. How? Employers must take action to support the employee-caregivers in their workforce, leveraging the career development and diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs and policies that have been shown to retain caregivers and help them thrive, personally and professionally.

Employers should note, however, that employees with caregiving responsibilities in Asia-Pacific are not a uniform group. Rather, the data reveals that each of the six countries studied displays unique needs and requires different means of support. What is consistent across these countries is the need for a holistic, employee-centric approach, comprising multiple programs and policies to build inclusivity and advancement pathways for caregivers.

About Our Research

Our survey was limited to people who were employed at the time. Employed caregivers, or “employee-caregivers,” were defined by survey responses—those who answered yes to any of the following questions:

- Are you responsible for the care of any children (under the age of 18) who live in your household (during at least part of your workweek)?

- Are you responsible (not just financially) for caring for sick or elderly adults, whether living in your home or for a substantial amount of time each week outside your home?

- Are you responsible (not just financially) for caring for a family member with a disability or health condition that substantially limits any of their major life activities?

Employee-Caregivers and Care Assistance—Defined

Employee-Noncaregivers. For ease of comparing survey findings, we use this term to designate those respondents to our survey who are employees but not caregivers.

Assistance. When we describe assistance, we refer to three broad types:

- Unpaid Assistance. This kind of assistance generally comes from family members, friends, and neighbors. Some employee-caregivers rely on unpaid assistance to provide care for their dependents so that they can attend to the responsibilities of their paying job.

- Paid Assistance. This kind of assistance encompasses paid babysitters, nannies, and personal-care attendants who work in home settings or institutions, such as daycare or elder-care facilities. Again, some employee-caregivers rely on paid assistance to temporarily take over the care of dependents so that they can attend to the responsibilities of their paying job.

- No Assistance. Some employee-caregivers report that they have no assistance, whether paid or unpaid. This means their dependents are not being cared for at all while the employee-caregivers are focused on the responsibilities of their paying jobs.

How We Quantified the Attrition Risk

Leveraging the forecasted change in the number of dependents in society and the number of employee-caregivers currently participating in the economy, we were able to calculate the number of net new employee-caregivers in the labor supply by country over time.

We assumed a fixed ratio of dependents to employee-caregivers. We also assumed no increase in the current availability of care access and assistance for employee-caregivers across countries. Caregivers with neither unpaid- nor paid-care assistance made up the following shares in the countries under study:

- China—30%

- Australia and Singapore—20%

- Japan—11%

- India—7%

- Indonesia—6%

Based on labor productivity, measured as GDP contribution per member of the labor supply, we estimate that the GDP contribution from unassisted, net new employee-caregivers in the Asia-Pacific workforce will be $500 billion.

These net new employee-caregivers will, without assistance, struggle to manage two jobs: employment and caregiving. This will not be sustainable for all. If 25% to 50% of them (which corresponds to 5 million to 10 million people) leave the labor force, the GDP lost will total $125 billion to $250 billion across the six Asia-Pacific countries under study by 2035.

We base our estimate on a conservative, low threshold, assuming that approximately 25% of those struggling to manage unassisted caregiving responsibilities in addition to their job will be able to leave the workforce without financial strain. This is in line with a previous US-focused BCG survey in which 20% to 40% of caregiver respondents indicated they could afford to leave the workforce if necessary to provide unpaid care. Of course, many caregivers may never afford to leave the workforce, although we expect their well-being and productivity to suffer if they remain employed.

Macroeconomic trends affecting our survey respondents support our rationale. Specifically, respondents tend to live in urban areas, where employee-caregivers may have less access to unpaid care than those in more suburban or rural settings; they may have moved into metropolitan areas away from family and friends. This could mean that the percentage of individuals with no care assistance seen in our respondent pool is higher than that of each country on average.

The economic risk from caregiver attrition is likely larger than estimated here given that caregivers’ attrition from the workforce also negates their participation in the tax transfer system—meaning that because many caregivers aren’t paid, they don’t pay taxes.

Companies and governments in Asia-Pacific can mitigate all of this by increasing care support. This could drive a step-change in how care is provided, while increasing the overall labor supply by providing more options that allow caregivers to go to work. Furthermore, the 85% of caregivers who do currently rely on paid and unpaid external care assistance will continue to require it.

Understanding the Scenario for Employee-Caregivers

Employers need to recognize the prevalence of caregiving and the challenges that employee-caregivers face. They are under strain at home and at work, often without adequate care assistance to cover their employed working hours. A deeper examination of the types of care assistance reveals that many employee-caregivers have no care assistance lined up—that is, their dependents are not in the care of another responsible adult during the employee-caregiver’s working hours.

Consequently, employee-caregivers are at risk of leaving the workforce, a costly outcome for employers: it’s expensive to find and train replacements. And when employees leave, they take their experience and institutional knowledge with them. Exacerbating the risk, employee-caregivers, because they tend to be ambitious, are particularly valuable to their employers.

To avoid attrition, employers should support the needs of this large and growing segment of their workforce and thereby improve retention. A compelling employee value proposition can be a source of significant sustainable advantage—helping to retain existing employees and attract new ones.

Finding the right ways to support the caregivers among the workforce begins with understanding their experiences and priorities.

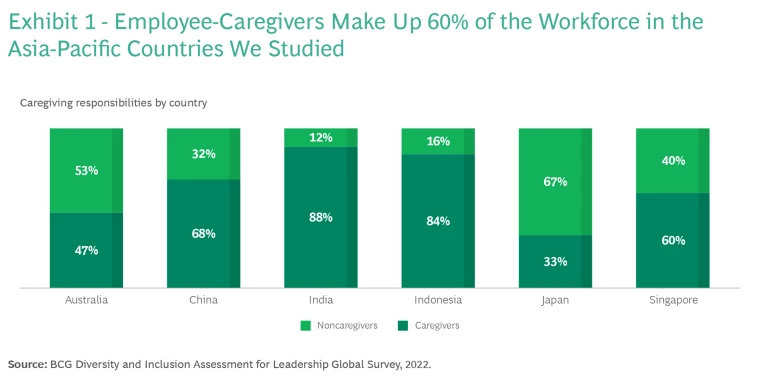

Employee-caregivers make up the majority of the workforce. Most employees in Asia-Pacific identify as caregivers. (See Exhibit 1.)

Aging populations will increase the need for elder care, driving an increase in caregiving responsibilities among working-age adults. According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, the ratio of the population older than 64 to the population of working-age adults (the age dependency ratio) will increase across the region by 2050, by at least 1.4 to 1.5 times (in Australia and Japan) and by as much as 2.1 to 2.5 times (in India, Indonesia, and China). (Data for Singapore was not available.)

Given the aging populations and the continued filial-piety expectations for care of elders in the home, we expect that the number of caregivers in the workforce will have grown by approximately 100 million, to 1.2 billion, by 2035.

Most employee-caregivers require assistance. More than 80% of employee-caregivers rely on care assistance to be able to attend to their paying job. The levels and forms of assistance vary across countries. Across the Asia-Pacific countries surveyed, respondents predominantly leveraged unpaid-care assistance or a combination of paid- and unpaid-care assistance in order to carry out the responsibilities of their paying job. (See Exhibit 2.)

In higher-income countries, paid-care assistance is already a necessity for many employee-caregivers. But BCG research has shown that paid care is in crisis, given its high costs and low availability.

In many Asia-Pacific countries, care assistance in institutional settings (such as daycare for children and residential care for elders), rather than in the home, is slowly beginning to gain acceptance. In China, for example, publicly funded childcare is notably abundant and accepted. But institutional care for adults is less accepted in many countries, especially India, Indonesia, and China. There is a social preference and expectation that dependent or elder adults will be cared for in the home. Unless there is a sudden move toward increased acceptance of, access to, and affordability of institutional care for the elderly, we expect demand for in-home caregiving for adult dependents to continue to increase.

Overall, more and more people will need to rely on paid care, straining the limited paid-care resources in Asia-Pacific countries, especially for employees with lower budgets. As a result, these caregivers could be driven from the workforce altogether—thus putting individual, company, and national income at risk.

Many employee-caregivers report poor well-being. At the moment, employee-caregivers are much more likely to anticipate staying in their jobs than they were during COVID-19. But that doesn’t mean the challenges they face are resolved. They are not.

Although they indicated in our survey that they feel valued and respected at work, employee-caregivers also reported lower levels of well-being relative to employee-noncaregivers. The strain of the added caregiving responsibilities likely accounts for this; our survey found that dual caregivers, whose strain is logically greater, experience the lowest levels of well-being. Employee-caregivers report adverse physical and mental well-being and higher levels of stress that impacts their relationships with friends and family. (See Exhibit 3.)

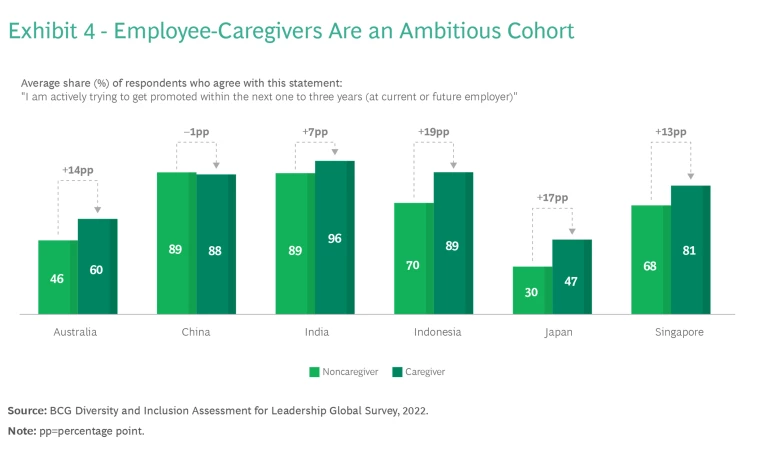

Employee-caregivers are particularly ambitious. Despite employed caregivers’ heightened well-being concerns, our survey found that 82% of employee-caregivers are actively trying to be promoted within the next three years; just 55% of employee-noncaregivers aspire to promotion in that time frame. Employee-caregivers are particularly likely to self-report an intention to seek promotion in India (96%), Indonesia (89%), and China (88%). (See Exhibit 4.)

Dual caregivers are the most ambitious. In fact, in Australia and Japan they are approximately twice as likely as those who are not caregivers to seek promotion within three years.

Employee-caregivers are also particularly likely to seek out mentors or sponsors—possibly to support them in their quest for promotions and possibly in response to the well-being challenges they face. Across the six countries under study, employee-caregivers were 27 percentage points more likely to seek mentors or sponsors (74% of caregivers did so; only 47% of employee-noncaregivers did).

In addition to promotions, employee-caregivers want greater compensation and career advancement opportunities—logical requests that will make staying at work worthwhile to employees, especially as the cost of child and adult care rises. (As an example, a KindiCare study reported in Financial Review found that costs have become so high in Australia that childcare expenses often consume 100% of one parent’s post-tax earnings, even with government support—effectively erasing the economic advantage of working.)

Losing employees presents a big challenge to an organization. Losing ambitious employees is an even greater blow.

Meeting Employee-Caregivers’ Needs

Given the experiences and feedback of people who are both holding jobs and providing care for a child, adult, or both, employers in Asia-Pacific must consider the very real possibility—and consequent impact—of an employee exodus. Employers need to keep these employees. And they need to keep them productive.

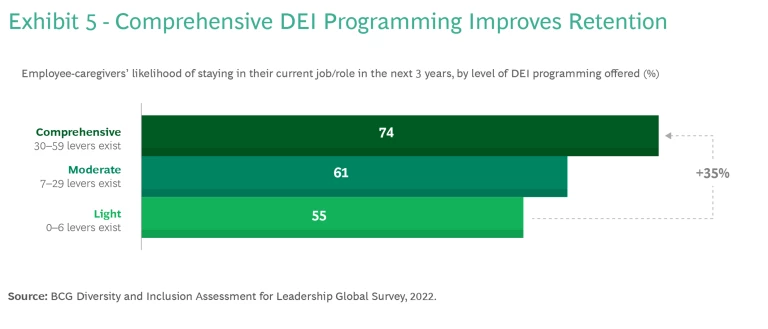

The good news: comprehensive, employee-centric DEI policies and programs—which include leadership accountability, antidiscrimination policies, paid parental leave, tracking of DEI metrics, and more—work. Exhibit 5 shows the supremacy of comprehensive versus light investments and the accompanying benefits of improved retention.

In our survey, we assessed 59 DEI initiatives that spanned the employee lifecycle, from recruitment to retention to advancement to leadership, and addressed functional, emotional, and well-being needs.

The highest inclusion and retention gains are secured in workplace environments that offer a comprehensive suite of employee-centric DEI policies and programs tackling the full gamut of caregiver needs. No individual program is enough.

Holistic programs with comprehensive investment in 30 or more DEI initiatives resulted in a 20-percentage-point increase in retention of employees who are caregivers versus those who are not. Employee-caregivers’ anticipated retention was 8 percentage points higher than that of noncaregivers at companies with comprehensive policies and programs.

Beyond retention, caregivers whose employers invest in comprehensive DEI policies and programs experience a 43-percentage-point increase in feelings of inclusivity relative to those whose employers offer more limited DEI programs—yielding a 7-percentage-point difference between the two groups.

Recommendations for Employers

Employers in Asia-Pacific can prepare for the coming caregiving crisis in the region by investing in supportive DEI policies and programs. Here’s how.

Understand the workforce. Employers should begin by learning who the caregivers in their organization are. Today, employers’ awareness of their employees’ caregiving responsibilities is limited, especially as it pertains to adult-caregiving responsibilities. Employers should seek to understand the prevalence of caregiving in their employee base and the types of support caregivers require at work.

And they should listen to what caregivers say they need. In Asia-Pacific, these are often country-level requirements:

- In India, where access to care is high overall but women’s workforce participation rates are low, focusing on women caregivers’ retention in the workforce could enable employers to retain this caregiver cohort and maintain diverse teams (which, previous BCG research has shown, perform better on average).

- In China, two priorities are apparent: increased compensation (amid concerns of stagnating real-wage growth) and a desire for a better work-life balance. Consequently, employee-caregivers here are changing jobs for better pay and the opportunity to pursue personal interests. Also, our interviews highlighted skyrocketing divorce rates in China; women here are thus particularly concerned about financial independence and economic security.

- Flexible work options are a top priority for caregivers across almost all countries, but especially in Indonesia. While Indonesian caregivers already enjoy more flexibility from high rates of unpaid-care assistance, flexible hours are still a priority. Identifying employee-caregivers who want such hours, and supporting them with different flexible work options, can also help set employers apart.

- Caregivers in Japan are likely to prioritize work-life balance above all other areas, including compensation. In a country with a culture of extreme working hours, interventions that help employees balance their personal and professional responsibilities could benefit caregivers and noncaregivers alike.

- Employee-caregivers in Singapore report one of the highest rates of ambition relative to those who are not caregivers, and this is reflected in Singaporean caregivers’ focus on compensation and career advancement opportunities. Given the high costs of living and high rates of migration that limit family assistance and increase the need for paid-care assistance, it is critical for Singaporean caregivers to be adequately incentivized to stay in the workforce with clear career advancement pathways.

- The story is similar in Australia, where the cost of paid-care assistance is often equal to (if not more than) a caregiver’s own income. Employers can ease the financial burden and financial tradeoffs by subsidizing care, providing on-site care, or offering flexible or personal-leave time to cover care-related responsibilities.

Employers across the region must invest understanding the unique needs and priorities of employee-caregivers in their market and offering policies and programs that are relevant.

Offer flexible work options. The needs of working caregivers include flexible work schedules and part-time options so that they can schedule their time at their paying jobs when paid- or unpaid-care assistance is available.

Employers will need to make sure that taking advantage of flexible work options does not stand in the way of career advancement. Performance assessments must be as objective as possible, gauging output against preestablished expectations. This means, for instance, that those who opt for remote work will not be put at a disadvantage compared with those who are onsite and more visible. And employees should beware of comparing the output of full-time employees with that of people who work at reduced capacity. Make sure that all staff are offered opportunities to grow within the company, whether they are full-time or not, and that open positions are posted for both full- and part-time roles.

Provide mentorship and sponsorship programs. Mentorship and sponsorship programs are powerful tools for creating a culture of caring and accountability. Employees say that having a mentor or sponsor helps them along their career path. And having a mentor or sponsor has been shown to increase long-term retention.

Across Asia-Pacific, three-quarters of caregivers have mentors or sponsors compared with just half of employees who are not caregivers. Notably, caregivers are four times more likely to find a mentor or sponsor via informal than formal channels, indicating the importance of this support to them.

Having a mentor or sponsor is correlated with positive outcomes for caregivers. Those with mentors or sponsors are more ambitious than those without (10 to 40 percentage points more ambitious depending upon the country). And employee-caregivers with mentors or sponsors are less likely to leave their jobs. When caregivers do not have a mentor or sponsor, their retention risk increases by 9 percentage points—in line with the attrition risk for employees who are not caregivers.

Ensure career development opportunities. Compensation is the most-cited reason for why respondents in our survey would consider leaving their jobs (42%). Career advancement opportunities that enable compensation raises and promotions are important to caregivers going forward, too. Of the employee-caregivers in our survey, 23% said they would leave their jobs if they didn’t have those opportunities.

Because employee-caregivers are ambitious and seek opportunities to grow, employers should engage in conversations with them about their goals and be sure to include them in opportunities for “stretch” assignments that will expand their opportunities and potential for advancement. Employers should build pathways that will make it possible for employees, including caregivers, to advance their careers.

In addition, companies should elevate senior role models who can highlight the work-life balance for caregivers and inspire them to seek new opportunities.

As with any program, employers should assess the efficacy of their career advancement support systems and adjust them accordingly, continuing to innovate to find the most successful solutions.

Build an inclusive culture. Improving employees’ experience of inclusion —making sure that they feel valued, motivated, that they belong, and that their perspectives matter—delivers enormous business value. Done right, inclusion positively changes the workplace experience. Providing role models for employee-caregivers is one way to increase feelings of inclusion. When these role models are candid about their own struggles and solutions regarding work-life balance, others will feel more comfortable speaking up about their needs and seeking support.

Inclusion is important to employee-caregivers: relative to those who are not caregivers, they are, on average across the region, 10% to 50% more likely to have declined a job offer, decided not to apply for a job, or left a job because they believed the company did not have an inclusive culture. Employee-caregivers indicate that they will vote with their feet when their workplace is not inclusive: employers should take heed.

Soon, employees in Asia-Pacific with caregiving responsibilities will find themselves struggling more than ever to deliver on two commitments: being productive, aspirational employees and being dedicated caregivers to children, elders, or both. Right now, most don’t see themselves leaving their jobs in the next three years, given the economy. But they have yet to encounter the surge in the caregiving need that is expected over the next decade. That surge could prompt them to leave, especially given the poor experiences they are already reporting and especially if their ambitions for promotion are not met.

Employees should not have to choose between personal commitments and professional aspirations. It’s in everyone’s best interest to ensure that they don’t have to. Now is the time for employers to support and keep them. If they don’t leave the workforce entirely, employee-caregivers—including ambitious individuals—are likely to seek employment from organizations that offer higher compensation, greater flexibility, and better career advancement opportunities.

Be that kind of employer.