Since the pandemic, hybrid work has become the new normal. This shift has decreased the demand for office space and will steadily lower its value, with implications for building owners and cities that rely on property tax revenue and the economic vibrancy that office workers generate. In a recent survey, BCG found that many office buildings are at risk of becoming “zombies”—with low utilization, high vacancy levels, and financial viability quickly slipping away.

Amid these developments, rising interest rates are piling significant financial pressure on building owners. New debt will be much more expensive, and when coupled with lower valuations could cause some owners to owe more than their buildings are worth; this, in turn, could lead to a wave of defaults that suddenly turn lenders into the owners and managers of office buildings.

Compounding these issues are technology advances such as generative AI that will further curtail the need for office space. Events are unfolding rapidly, and property owners, city leaders, and lenders must begin working together now to address the challenges that lie ahead.

Becoming a Zombie

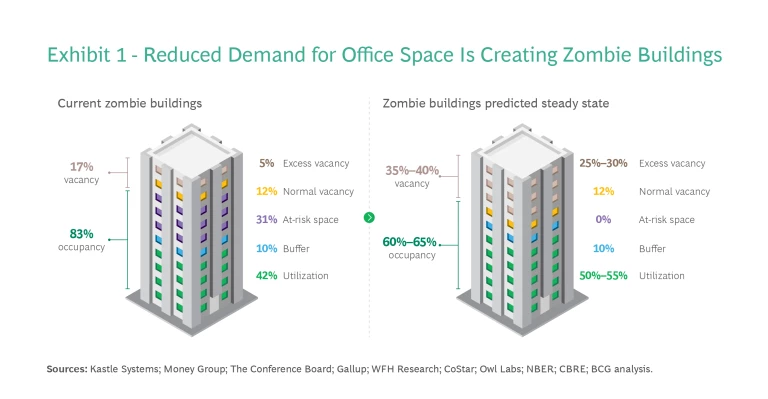

Buildings become zombies when vacancy rates and unused space under lease drive utilization to 50% or less. Many buildings are already at that mark. Our research found that, on average, vacancy rates have increased from 12% to 17%, while utilization has plummeted from 70% to 42%, a decline driven by a surge in what we call “at risk” space. This category represents the enormous amount of space under leases that are unlikely to be renewed.

The at-risk category exists because the office market shifted so suddenly that leases have not caught up. During the pandemic, many tenants signed short-term leases, biding their time until they had a better idea of what the future of work would look like. Before the pandemic, the average corporate lease was for five to ten years, while most leases today are for less than five years. As a result, 60% of office leases are set to expire in the next three years.

Assuming these trends continue and organizations right-size to fit new levels of demand, utilization may tick up slightly from today’s depths, but still only 60% to 65% of current US office space will be needed. (See Exhibit 1.) That means about 1.5 billion square feet of office space could become obsolete, which would translate into $40 billion to $60 billion of lost revenue for building owners.

Of course, not all of that 1.5 billion square feet will become vacant. Landlords are already offering months of free rent and other concessions to keep tenants from abandoning their leases, hoping they will be willing to pay for the space in the future. It’s possible that downtown office rents will eventually drop far enough to entice companies once priced out of those areas, but that would mean just a shift in occupied space, not a net increase.

Not all office buildings will suffer equally, either. We expect to see a “flight to quality”—that is, to amenity-rich office buildings in attractive locations (with access to mass transit, good restaurants, and green spaces, for example). In addition, we expect that buildings occupied by tenants that require employees to work on site will be largely shielded from this impact. Conversely older, cubicle-based buildings catering to office workers but lacking in modern amenities will suffer the most.

The Specter of Rising Rates

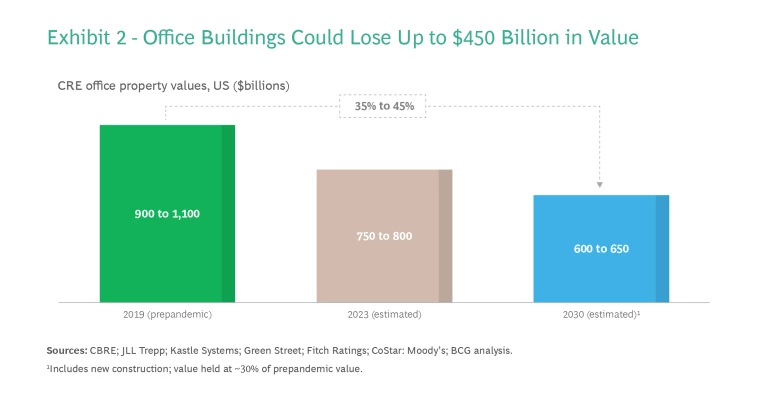

Increasing vacancies and lower utilization rates are not the only forces threatening to turn office buildings into zombies. Rising interest rates will have an enormous impact on companies that borrow at a floating rate and those that need to refinance, making new debt very expensive. For property owners, the math is inescapable. When rates rise and spreads widen for real estate financing, the value of office buildings declines. With both demand falling and financing getting scarcer and more expensive, we expect building values to drop by about 40% from prepandemic levels over the next 12 to 36 months. (See Exhibit 2.) Investors have already marked down office REIT stocks by this amount.

Furthermore, buildings are, on average, 60% leveraged, so a 40% drop in value means many will be worth less than the debt owed. Defaults will rise as a result, and lenders must be prepared. In February, a fund managed by Brookfield Properties defaulted on $784 million of loans on two well-known office skyscrapers in downtown Los Angeles, which some say could signal a turning point for the US office market. Even for owners that avoid default, less access to capital could keep them from investing to improve properties in ways that would increase occupancy.

Where Zombies Roam

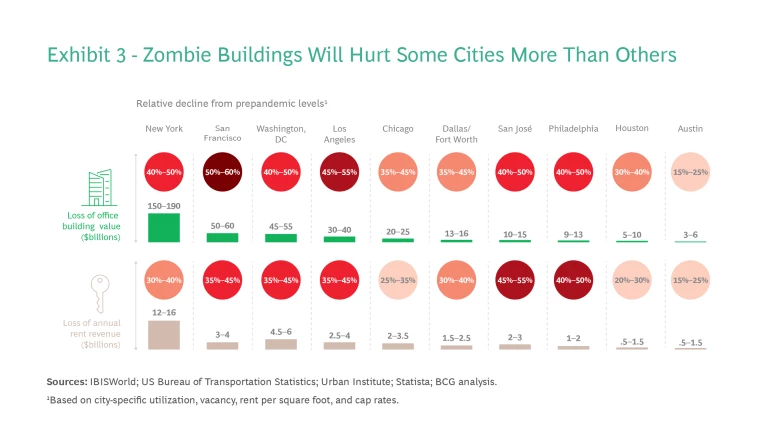

There will be zombie buildings in most major office markets, but the impact will not be felt equally. (See Exhibit 3.) Cities with a higher concentration of office buildings than residential and retail, and those whose economies rely on industries amenable to remote work (technology and finance, for example), face greater exposure and risks. Gateway cities that experienced some of the heaviest inflows of investor capital over the past decade—and that witnessed record-breaking office building valuations as a result—will be hardest hit.

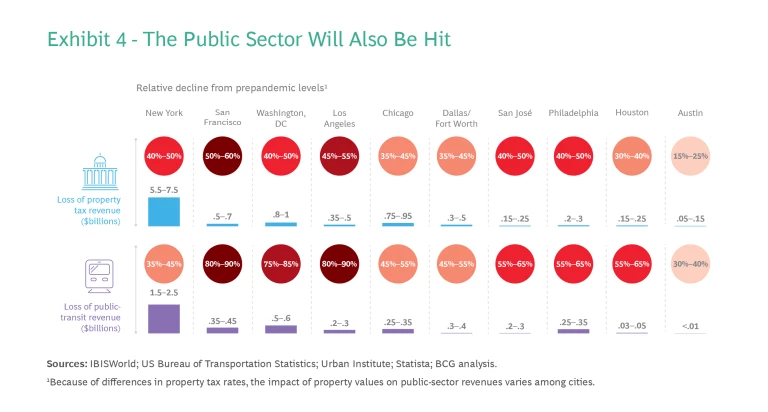

The losses will not be felt by the private sector alone. The public sector will lose property tax and public-transit revenue of $15 billion to $25 billion nationally, according to our estimates, with the bulk of those loses occurring in ten cities. (See Exhibit 4.) Sales tax revenue will also take a hit. In central business districts across the country, in-person spending is down in areas with high concentrations of office buildings, driving up retail vacancies and causing downtown areas to deteriorate further.

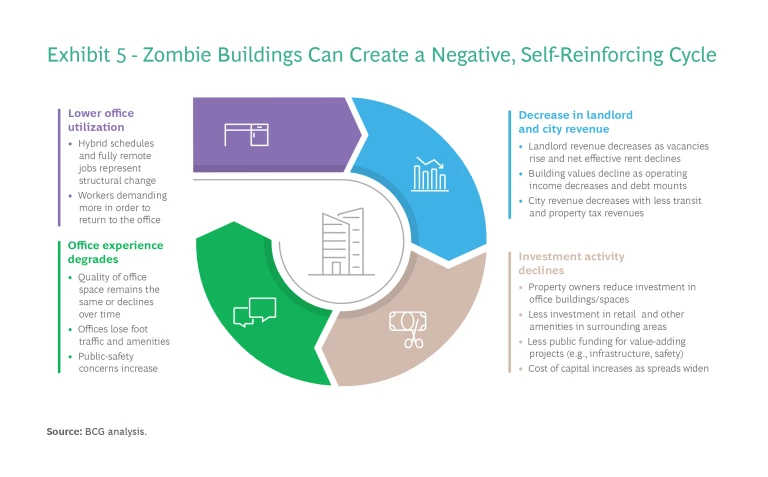

A self-reinforcing vicious cycle is emerging. (See Exhibit 5.) Lower office utilization leads to decreased spending at surrounding businesses and, as leases turn over, less rent revenue. This reduces the capital available for investment in building improvements, which further decreases building values and capital for investment. As utilization stays down, surrounding businesses that cater to office workers close or relocate, creating more vacancies and often raising public-safety concerns that cities struggle to combat with fewer financial resources.

Breaking the Downward Spiral

The pandemic created a permanent change in workplace behavior, so even a national economic rebound or a pause in interest rate hikes will not cure the problem. The private and public sectors must take joint, strategic action to break the cycle and reimagine cities’ downtown areas.

Next Steps for Property Owners

Property owners need to assess their commercial real estate (CRE) portfolios and set a strategy to revive their zombie buildings depending on property characteristics, neighborhoods, markets, finances, and city taxes and incentives. This assessment will divide the portfolio into five categories, on a spectrum from buildings that can remain as is to those that should be relinquished.

Remain. These buildings have maintained strong demand and operating income. They include newer Class A and A+ buildings that have retained high occupancy, rent growth, and renewals owing to quality amenities, as well as Class B and C buildings that are well utilized by tenants that require on-site staff. Transforming some of the capacity to flex space could increase the attractiveness and utilization of these buildings.

Renovate. These buildings have experienced a moderate decline in operating income and are in markets experiencing tailwinds for office growth. They are mostly older Class A and B+ buildings. Meanwhile, higher-quality office buildings located in these areas may be enjoying high occupancy and rent growth, thanks in part to good local transit and amenities such as good restaurants and stores. Here too, conversion to flex space should be considered.

Property owners need to assess their commercial real estate portfolios and set a strategy to revive their zombie buildings.

Repurpose. These buildings are no longer economically viable as office space but can be adapted to other uses such as hotels or residences (as long as they have narrow floorplans and are not large square office towers). Thy include some Class B and C buildings in areas with low demand for office space and accessible schools and child care.

Redevelop. These buildings are no longer viable as offices and are not fit for adaptive reuse. Redevelopment will require strong support and incentives from the city but could benefit neighborhoods in need of significant transformation. At a low enough price and with the right incentives, for example, even some office towers with large square floorplans might be adapted to residential or hotel use.

Relinquish. These buildings are no longer viable as offices, are not fit for adaptive reuse, and will not attract public support for redevelopment. Here the best choice might be to default, hand over the keys, and move on. In these cases, some lenders will find themselves in a new and unfamiliar position as owners and managers of office buildings.

Next Steps for Cities

Cities and local governments must launch partnerships that include public agencies, local interest groups, and the private sector (neighborhood associations, large employers, CRE service providers, and developers, for example). Their strategies should include short-term efforts (less than two years) and medium-term efforts (two to four years) to establish a financial baseline, drive building utilization, support the redevelopment of downtown areas, and replace lost tax revenue. The ultimate goal should be to revitalize downtown areas and make them destinations for living, working, and playing.

Establish a financial baseline. In the short term, city and local governments must assess office buildings for their likelihood of default and low occupancy and for the feasibility of conversion to affordable housing. They should estimate budget shortfalls from lower tax revenue and create local task forces with private-sector players (such as large employers, CRE providers, and developers). In the medium term, they should monitor developments and reprioritize as needed.

Drive CRE utilization. In the short term, governments should develop a neighborhood revitalization strategy to make business districts live-work-play destinations. They can invest in maintaining public spaces and keeping them safe, with a special focus on transit. And given the size of the government workforce, implementing a return-to-work policy could help boost the vitality of downtown corridors.

The ultimate goal should be to revitalize downtown areas and make them destinations for living, working, and playing.

In the medium term, cities should evaluate, top to bottom, government impediments to action—whether in the permitting process, zoning, or taxes—in order to increase the attractiveness of downtown areas. This could include developing green spaces, improving the speed and connectedness of public transit, and zoning for more restaurants and bars. Governments could also move their offices to bolster key corridors and better utilize public transit.

Support the transition to reuse. In the short term, cities should seize opportunities to repurpose office space for affordable housing. In the medium term, they can revise zoning to allow for more housing, hotels, and retail and office space. They can also provide incentives (such as tax breaks and subsidies) for conversions to residential use and for energy-efficient retrofits.

Replace lost revenue. In the short term, governments should develop a comprehensive plan to close the budget gap (by delaying property reappraisals that would lower taxes, for example) and make better use of public spaces for art, music, and theater programming that would draw people downtown. In the medium term, governments can work with partners to reimagine revenue models (such as by increasing tourism, creating an arts district, or improving public spaces) and make the necessary changes to zoning and development regulations. It’s also important to carefully consider the city’s current and future competitive advantages and invest in those areas.

Next Steps for Lenders

Finally, in this era of higher interest rates and tighter credit, lenders will play an important role in managing zombie buildings and the decreased demand for office space. By working closely with property owners and city governments, lenders should aim to prevent a wave of defaults that could overwhelm urban centers, force them to become owners and managers of office buildings, and start a spiral of declining property values. They’ll need to implement risk management strategies, build internal capabilities to restructure loans near or in default, and develop marketplaces to sell those loans. But lenders won’t just be coping with old, problem loans. There will also be new business opportunities as owners and cities look to redevelop properties. To take advantage, lenders will need to ensure that they have the right products and expertise in place.

Lenders should aim to prevent a wave of defaults that could overwhelm urban centers and start a spiral of declining property values.

Implement risk mitigation and servicing strategies. To better understand their risk exposure and develop mitigation strategies, lenders need to stress test both their loan books and their investment portfolios (including commercial mortgage-backed securities). They should identify early warning signs of trouble both general (city vacancy rates, for example) and specific (building utilization, lease expiration, and lease rollups) and develop mechanisms to monitor these metrics more frequently.

Build internal restructuring capabilities. Even with mitigation strategies in place, defaults will occur and borrowers will need assistance. Lenders should work with borrowers to develop options (such as web applications) that can either prevent or delay defaults. Lenders should review their current operating models to ensure that they can scale their debt restructuring/nonperforming loan management capabilities. This will probably require that they upskill current employees , hire talent, or partner with a specialist firm.

Develop a marketplace. Lenders are not in the business of owning and managing office buildings, so they will need to transfer these distressed and repossessed properties to others. That will require partnering with deep-value investors, land banks, and others that can take properties off the balance sheet. Lenders may also need to create a marketplace for distressed assets by, for example, building, buying, or partnering with electronic auction platforms.

Subscribe to our Public Sector E-Alert.

Expand the product portfolio. Even in this down cycle for office buildings, some property owners will want to renovate, repurpose, or redevelop properties. For lenders, this will create opportunities. But they will need to carefully consider the types of financial products that will be in demand (for purchase, renovation, rehabilitation, or conversion to residential) and determine which they have and which they should add.

There will be a major recalibration of the office market over the next three years, forcing the nation to deal with a surge of zombie buildings and very stressed urban corridors. Given the stakes, property owners, cities, and lenders must begin working together to rethink building uses and pursue creative downtown revitalizations.

The authors would like to thank Marco Werner, Nico Dovetta, Sarah Feldman, Alexandra Salgado, Kenny Nishimura, Yi Gu, and Sean Lee for their contributions to this article.