The

fashion industry

is becoming increasingly aware of the environmental impact of its waste problem: 87% of the material used in clothing production is eventually put in landfills or incinerated; less than 1% is recycled into new

While efforts to transition to circular and sustainable business models have long been underway, progress has been slow. Today, circular solutions are far outpaced by the sheer scale of consumption and production. The urgency of the climate crisis and the enormity of the waste problem call for a greater focus on solutions to reduce fashion’s footprint in the near term.

Promoting the reuse of garments is imperative; however, all garments eventually reach an end-of-life moment, when they can no longer be reused. Achieving true circularity in the fashion industry requires advanced recycling solutions to prepare for the end of life of the vast inventory of clothing in circulation that was manufactured using traditional, linear methods and for textiles that are difficult or impossible to recycle using available technologies.

Rather than focusing solely on waste reduction, the fashion industry should adopt a pragmatic approach to circularity and double down on end-of-life recycling solutions, ensuring that textile waste stimulates the production of new garments rather than growth in landfills.

Tackling Fashion’s Waste Problem

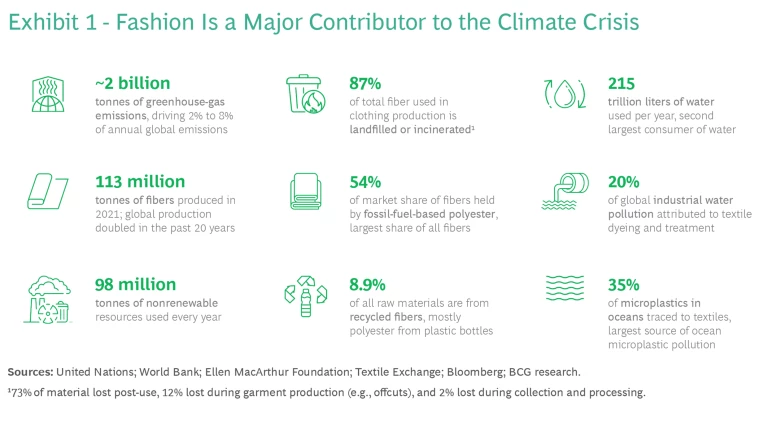

The fashion industry’s overreliance on natural resources for production, coupled with unsustainable waste management and excess production, has had a devastating impact on the environment. (See Exhibit 1.) Repercussions of the industry’s practices include deforestation, loss of biodiversity, water scarcity, soil degradation, chemical pollution, and a massive carbon footprint.

Fashion’s traditional linear “take-make-waste” model contributes to the growing climate crisis by releasing greenhouse gases and using virgin inputs for new production. Circularity offers a promising solution by establishing a closed-loop system that enables textiles to re-enter the value chain, thereby prolonging the value capture of materials.

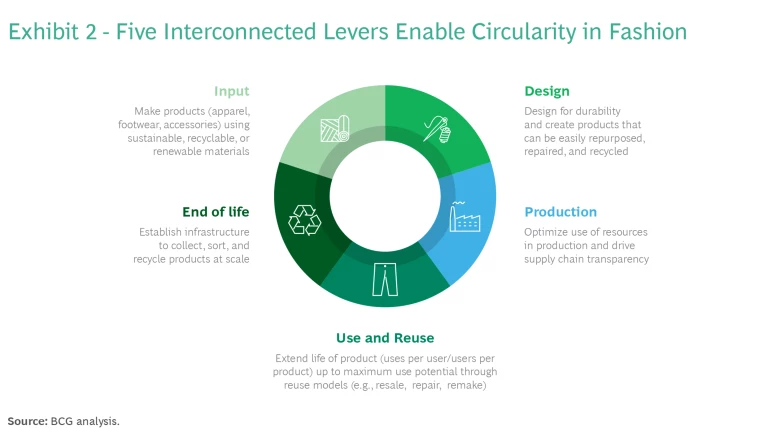

The circular value chain holistically addresses waste through five interconnected levers. (See Exhibit 2.)

Each step, from material choice to circular design, is a critical enabler for the end-of-life stage, which allows products to be recycled and reused over and over again. For example, technical fibers are often derived from nonrenewable resources and take a long time to decompose in landfills. Increasing the recycled content in technical fibers reduces the demand for virgin resources, conserves energy, and minimizes waste. Given the interdependencies across the value chain, achieving a fully circular value chain will require the maturation of each step, which takes considerable time.

- Input. Increasing the availability of circular inputs at par with alternative virgin materials will entail long-term innovation.

- Design. Creating products using circular and sustainable design principles will require industry-wide transformation including reevaluation of design education in schools.

- Production. Driving transparency and circularity in production will involve redesigning supply chain processes.

- Use and Reuse. Increasing adoption of reuse models (resell, repair, remake) will require significant shifts in consumer behavior.

- End of Life. Establishing an infrastructure to collect, sort, and reuse or recycle products at scale is a complicated endeavor involving multiple actors. (See the following section.)

As we continue to make progress in advancing long-term levers like materials innovation and circular design, there is a heightened need to focus on end-of-life circularity solutions to mitigate fashion’s waste crisis in the near term. We must prioritize the development and scaling of advanced recycling systems that can convert multiple sources of textile waste (for example, post-consumer, manufacturing scraps, damaged goods, and excess inventory) into reusable materials, thereby increasing the availability of virgin-equivalent circular inputs for manufacturing.

The End-of-Life Landscape

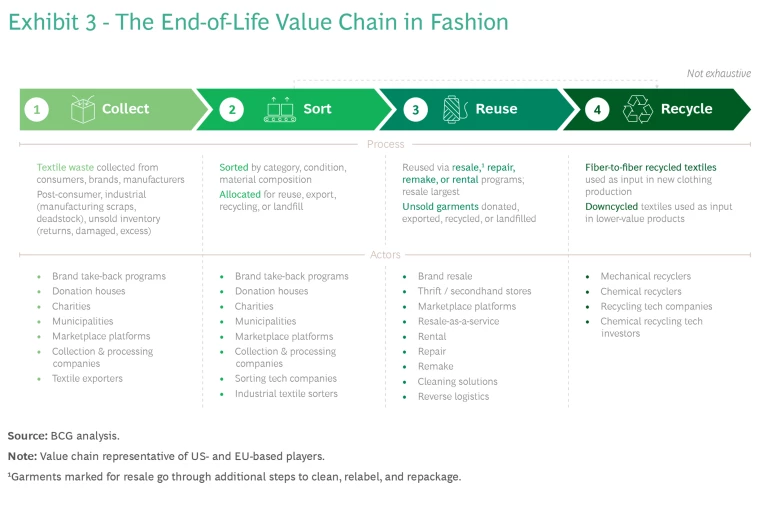

Before a garment can be recycled, it must go through a series of steps executed by several players working together. Textile waste is collected from consumer and industrial sources; sorted by category, condition, and material composition; and then designated for either reuse or recycling. (See Exhibit 3.)

The process is far from being perfectly linear and straightforward. Instead, it is a complex and intricate web of diverse connections and actors characterized by several complications. Recognizing these complications is the first step toward designing appropriate interventions.

- Multiple Concurrent Processes. Garments rarely make it through the end-of-life value chain in a streamlined, linear manner. Instead, a garment may go through multiple permutations of collection, sorting, and reuse before reaching the recycling stage. For example, a garment collected, sorted, and designated for resale may go unsold, be exported, and go through another round of sorting to determine its next destination (resale, recycling, or landfill).

- Interdependencies Between Actors. No single player in the value chain has in-house capabilities to execute all the necessary steps in the process. Actors specialize in different parts of the value chain and work together to facilitate execution. For example, recyclers rely on sorters to receive presorted feedstock, and brands rely on resale-as-a-service (RaaS) partners to provide the backend infrastructure for their take-back programs. This system generates efficiencies but comes with logistical and operational complexities.

- Limited Connectivity Between Players. Certain steps in the value chain have geographical hubs that exacerbate the logistical inefficiencies in the process. For instance, the supply of feedstock comes primarily from Western countries, while many of the advanced chemical recycling plants are in Europe, and the production of new garments that require recycled materials occurs in Asia. This geographic fragmentation, combined with the high cost of transportation, hinders the optimal matching of demand and supply.

- Evolving Business Models. Growth in resale and recycling programs has led to the emergence of new players, technologies, and ways of working. Actors are experimenting with different circularity initiatives to identify their optimal model. For example, hundreds of brands have ventured into resale, some doing it in-house and others in partnership with RaaS companies or third-party consignment marketplaces. The frequent introduction of new business models, while representing growth, adds further complexity to a crowded and disparate landscape.

Gaps in the End-of-Life Value Chain

In addition to the complexities that drive inefficiencies in the end-of-life process, there are several gaps where circularity efforts fail and merely postpone landfilling of textile waste. These gaps, discussed below, must be bridged to promote a perpetual cycle of true circularity.

Collection. Significant volumes of reusable and recyclable garments are either not being collected or are being discarded due to barriers that limit consumer engagement and brand adoption of reuse and recycling.

- Collection efforts are fragmented. Consumers find the disparity in collection efforts across brands, municipalities, and other players confusing and inconvenient. The sheer number and variety of collection options can be overwhelming, and many require making trips to stores to physically deposit clothing. As a result, many consumers simply dispose of unwanted clothing. Mail-backs or pickups, while easier for consumers, are more expensive and logistically complex for brands. Collecting low-value items in smaller quantities from a large pool of consumers on a recurring basis can make it challenging for collection businesses to achieve economies of scale.

- Incentivization for take-back schemes is incomprehensive and insufficient. Many consumers are not sufficiently motivated by monetary incentives to return used clothing. For example, online consignment marketplaces offer commissions but have long processing times and low payouts. A lack of comprehensive incentive mechanisms leads to unfavorable consumer tradeoffs between the value (financial or non-financial) and effort of take-back programs.

Sorting. Inefficiencies in the sorting market, driven by nascent technologies and inadequate connectivity, inhibit the optimal processing of garments.

- Sorting processes are largely manual and labor intensive. While there has been notable progress in optical-fiber-sorting innovations. such as infrared and visual spectrometry, widespread adoption of these technologies in textiles will require them to become economically viable. Missing or inadequate labeling of garments further compounds the challenge for sorters to accurately identify a garment’s material composition.

- Geographical barriers are driving logistical inefficiencies. In the sorting market, the distance between players is a primary factor, and logistical barriers often prevent optimal recycling practices. Typically, sorters source from regional collectors within their geographical network to optimize for the lowest cost of freight and sell to the highest-bidding recyclers. However, recyclers may lack the capacity or capability to recycle a sorter’s garments. Alternatively, because of the economics of sourcing, that feedstock may not be viable for recyclers. The inventory that can’t be sold to recyclers often ends up in landfills. Growing adequate regional sorting and recycling hubs, particularly for chemical recycling, will be critical to overcome these geographical and logistical barriers.

Reuse. Reuse models (resale, repair, or rental) without accompanying measures for products whose lifecycle cannot be further extended are incomplete solutions for achieving circularity.

- Garments collected for resale may still end up in landfills. Only a small percentage of clothing collected for resale is ultimately sold. Resale take-back programs by brands, donation houses, and third-party players often lack supporting strategies to manage unsold clothing. Limited storage capacity and holding costs exert additional pressure to offload garments quickly. As a result, rather than spending resources to repurpose or recycle unsold inventory, players find it more economical to destroy those garments.

- Exporting clothing does not ensure reuse. A considerable amount of post-consumer clothing is either immediately exported upon collection or exported if it does not sell through resale channels. However, the supply of secondhand clothing is substantially higher than the demand in importing countries, resulting in a significant amount of clothing being landfilled abroad without ever being reused.

Recycling. Open-loop and closed-loop recycling have significant limitations:

- Open-loop recycling does not enable full circularity. Open-loop recycling downcycles textiles into lower-value use items (such as rags and upholstery stuffing) that are usually landfilled at the end of their usable life. While preferable to a purely linear “take-make-waste” model, open-loop recycling is not a truly circular solution.

Closed-loop recycling technologies have not achieved scale. Closed-loop recycling, which converts textile waste into fiber that can be used in new material production, has yet to achieve the scale required to process the full spectrum of materials produced and volumes of waste generated. There are two main methods of closed-loop recycling:

- Mechanical closed-loop recycling involves strict material processing requirements (for example, mono-materials, undyed), which can make it difficult and expensive for recyclers to source feedstock. The process also shortens and weakens material fibers, requiring them to be blended with virgin fibers to yield quality yarns.

- Chemical closed-loop recycling tackles the limitations of mechanical closed-loop recycling by targeting materials that are tough to recycle (such as polyester and polyblends) and producing virgin-equivalent output. However, these solutions are nascent, have limited processing capacities, and are not yet economically viable.

- The economics of recycling are unfavorable for brands. Many brands destroy unsold inventory (for example, damaged goods, returns, excess) at the end of a season instead of reselling or donating it. While recycling that inventory would be a preferable alternative to destruction, it is often cheaper for brands to dispose of excess product than to repurpose or recycle it. Some countries, such as France and Germany, have passed legislation banning companies from destroying unsold or returned garments. We believe that introducing regulations that would make recycling financially favorable for brands—for example, by offering tax benefits—would reduce resistance to similar legislation worldwide.

Subscribe to our Climate Change and Sustainability E-Alert.

Toward a Circular Future

While several solutions to advance circularity from an end-of-life perspective exist, their adoption by the fashion industry remains limited. Rather than waiting for the next breakthrough technology or becoming paralyzed in the pursuit of perfection, the industry must seize opportunities to take meaningful action now. To accelerate progress toward a circular future with positive financial returns, the fashion industry must pursue the strategies discussed below.

Mobilize Demand for Recycled Output

The limited inclusion of recycled textiles in clothing lines today is driven by the low availability and high price of recycled fibers compared with alternatives. Brands rely on recycled plastic waste for their sustainable collections while waiting for recycled textiles to become economically viable. This is particularly true for recycled polyester, as most brands use recycled plastics (for example, plastic bottles and packaging) from other industries instead of using regenerated polyester from the garments they produce.

This has resulted in a recycling paradox, where textile-recycling technologies are unable to scale without sufficient demand for their output from brands, and brands are hesitant to increase their use of recycled textiles until these technologies become more cost-effective. To break this cycle, brands must increase their use of recycled textiles available today while also investing in the growth of closed-loop textile-recycling technologies to drive demand and achieve economies of scale.

Adopt Investment Models That Accelerate Expansion

While investment is needed to support early-stage innovations and to scale promising technologies, the latter is harder to achieve given high-risk, capital-intense requirements to scale. There are many promising technologies, particularly in closed-loop recycling, that are ready to be scaled today. However, most players find it challenging to scale their operations beyond a single commercial-scale plant.

Alternative investment models, such as licensing and joint ventures, can reduce upfront capital needs and allow innovators to overcome current funding constraints to scale. Although the tradeoffs between pursuing these alternative investment models and establishing owned-and-operated factories are not unique to textile recycling, prioritizing the former can deliver speed to scale with favorable economic returns.

Underpin Recycling with Sorting Infrastructure and Technology

Scaling recycling without developing the supporting infrastructure and technology for collection and sorting will create a feedstock gap. Closed-loop recyclers have high purity standards and can primarily process mono-materials (for example, pure cotton). Purity constraints, combined with the difficulty in accurately identifying the composition of post-consumer waste, make it a less desirable source of feedstock despite being considerably larger than industrial waste.

As demand for recycled output increases, competition for pure feedstock will also increase, impacting its supply. To address this issue, it is essential to scale closed-loop recycling technologies that can process a wider variety of blended materials and sorting technologies that can accurately identify material composition, making post-consumer waste a more viable source of feedstock.

Maximize Impact Through Concerted Efforts

Individual, small-scale efforts will not achieve the impact required to tackle fashion’s decentralized waste problem. Industry actors have launched initiatives and joined coalitions and alliances to create collective action. Despite the commitment, many players chase communal goals individually, resulting in a sustainability landscape saturated with well-intentioned but fragmented and overlapping initiatives.

Actors must give a higher priority to consolidating efforts at scale than to pursuing individual competitive advantages. For instance, brands can consolidate take-back programs, pool investment in technologies, and share best practices to amplify and accelerate impact. Chemical closed-loop recyclers can also work together to ensure that impurities extracted during processing (that is, materials a particular technology cannot recycle) are passed on to recyclers with suitable technology. For example, a polyester closed-loop recycler can pass on the cotton extracted during processing to a cotton closed-loop recycler.

Build Momentum by Starting Today

In searching for opportunities with the highest potential for impact and visibility, brands often overlook short-term prospects that can move the needle. But brands can gradually build end-of-life business models by starting with initiatives that fit into their current ecosystem. One such opportunity could be forging partnerships that unify incentives, remove friction, and create revenue streams. For example, brands can sell their excess inventory directly to closed-loop recyclers, thereby making it easier for recyclers to source feedstock with known material composition.

Brands can further integrate circularity into their core business operations through versatile tools that drive business and social value. For instance, digital IDs enable brands to remain connected to their consumers beyond the point of sale and generate future revenue streams by offering authentication and traceability. Additionally, digital IDs can be used to engage consumers via marketing and storytelling; educate them about the product’s origin, materials, and care; and enable them to eventually resell, repair, or recycle the product.

Defining Your Circularity Agenda

In addition to reducing waste and emissions, pursuing circularity can yield significant economic value. Circular business models are expected to grow to approximately 23% of the fashion market by 2030, representing an estimated $700 billion

Early movers in fashion circularity recognize that implementing circularity at scale requires an industry-wide transformation. From setting ambitious goals to launching diverse initiatives across the circular value chain, chief executives have demonstrated their commitment to advancing circularity in the fashion industry. Nevertheless, despite the urgency surrounding circularity, many companies struggle to identify where to begin their journey. Pressure from stakeholders for immediate action often leads organizations to replicate frameworks applied by other brands and implement circularity initiatives in an ad hoc, piecemeal manner. However, when it comes to circularity strategies and models, no single approach fits all.

BCG has supported many fashion brands with their circularity agenda, and in our experience, a successful circularity strategy is comprehensive and tailored to the overall business. For example, we applied our integrated circularity framework, called

Circelligence

, to build and execute a circularity strategy for an athletic- apparel and footwear brand in three phases:

- Set a vision. Establishing a credible baseline is a crucial first step for any brand looking to embark on a circularity journey or build on existing initiatives. Using our proprietary tools, we baselined and benchmarked the brand's circular performance relative to its peers. This initial assessment allowed us to define the brand's ambition level and establish a clear circularity definition and vision for the organization.

- Build plans. We identified circularity opportunities across the brand’s value chain and prioritized initiatives based on impact and feasibility. Circularity intersects with many areas of a business; however, it is often treated as an isolated function, with teams working in silos. BCG’s deep experience across the end-to-end value chain allowed us to recognize cross-functional synergies and develop an integrated circularity plan.

- Drive to action. We developed detailed implementation roadmaps for prioritized initiatives and launched pilots to test and refine them. We also crafted authentic and compelling circularity communication materials, including narratives and reports, recognizing that in today's context of increased scrutiny of sustainability claims, transparency is more crucial than ever.

By partnering with the brand from conceptualization to implementation, we accelerated its circularity journey and set it up for success in the long term. The brand embraced circular design principles and scaled up the use of circular inputs in its new products, among other initiatives.

As long as revenues remain inextricably linked to linear production models, mobilizing for change will be difficult. Ultimately, though, if industry interest in circularity fails to translate into impact, the status quo will be disrupted through policy and regulation. Widespread regulation curbing the destruction of textile waste is on the horizon, and those who fail to respond proactively will struggle to survive. It’s time to pivot away from experimenting in circularity to fundamentally rethinking end-of-life strategies.