Will Europe’s energy crisis be remembered as the event that catalyzed a transformation or bemoaned as a major opportunity missed? The answer, which has enormous implications for Europe’s industrial economy, will start playing out in the coming months.

Industry and government leaders feared the worst when Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022 and subsequently cut back gas supplies to Europe. The disruption sent gas wholesale prices soaring, with increases of up to 22 times 2019 levels in Germany and more than 15 times greater in some other European countries. Many predicted rationing, rolling blackouts, and economic calamity.

Fast action by government and industry, in addition to some lucky breaks with the weather, forestalled catastrophe. Europe’s economy performed stronger than expected in 2022 (1.9% inflation-adjusted GDP growth in Germany over 2021, for example), but it would be a mistake to believe that industry will continue to simply “pull through.” The challenges to Europe’s energy system are structural, and the shift in gas supply from historically cheap Russian pipeline supplies to more costly liquid natural gas (LNG) imports highlights a major weakness. Gas is not the only issue. Europe remains dependent on single suppliers for up to 50% of key resources such as rare-earth minerals and many prefinished goods. The climate challenge of reducing some 55% of CO2 emissions by 2030 has not gone away.

The energy crisis remains very much present, but within it lies opportunity.

The crisis remains very much present, but within it lies the opportunity for a structural change that addresses several problems: maintaining a consistent and competitive energy supply, reducing CO2 emissions, and putting Europe’s economy on a competitive footing for decades to come. To be sure, in the near term, industry needs to continue taking the requisite steps to optimize energy use and procurement and double down on general cost cutting. But these actions have their limits and do not address Europe’s structural energy issues. Industry and government also must work toward a more ambitious, comprehensive, and long-term solution: using green markets and technologies to address energy supply and carbon impact while releveling the playing field with other nations, such as the US and China.

Most new technologies carry a near-term cost burden compared with fossil fuels and feedstocks, but the more salient point is that Europe is structurally disadvantaged from a cost perspective on fossil fuels compared with its main global competitors—putting all subsidies aside—while the bloc is largely cost competitive with major regions such as North America and China in many renewables, such as wind, solar, and green hydrogen. Green energy therefore comes at similar costs in Europe as in the US and China, and it taps into a large economic growth opportunity while contributing to solving an existential global challenge.

The current energy situation is an unprecedented challenge, but Europe’s industry has weathered many storms, including the 2008 financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic. A green transformation can turn coming disaster into opportunity. This reality makes action a strategic imperative. Here’s our analysis of what needs to happen and how Europe can pull it off.

A Crisis Averted…

While the dramatic energy price increases in 2022 (including peaks of more than €300/MWh for wholesale natural gas and more than €800/MWh for electricity based on day-ahead prices) largely caught industry by surprise, many companies reacted quickly and decisively to reduce consumption and, where possible, secure alternative sources (primarily LNG). These steps and a warm winter produced high gas storage levels of 75% across the EU in February 2023, a record for that time of year, and in some countries 40 percentage points over the storage levels of the previous year. LNG volumes are expected to rise as additional terminal capacity and contracted volumes become available.

That said, about half of industrial companies were forced to cut or temporarily suspend production, especially in the building-materials sector, which was also affected by supply chain shortages, rising mortgage rates, and an overall reduction in construction activity. A third of the companies surveyed by BCG in Germany in late 2022 had started to source raw materials and prefinished goods abroad, and 18% had shifted production to countries with better cost structures.

…Is Not a Problem Solved

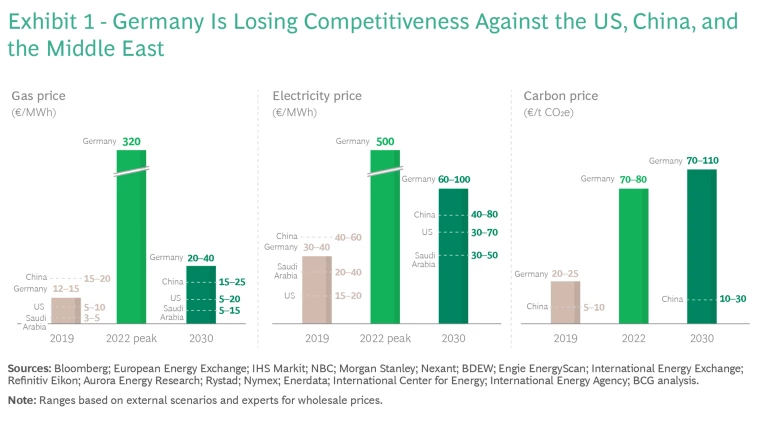

In the wake of the storm, it would be a mistake to assume that energy prices will simply return to precrisis levels. To fill the gap left by reduced gas supplies from Russia, Europe—and especially Germany—will need to rely heavily on LNG, resulting in an increase in imports of 20% to 40% in 2025 over 2021. LNG will likely set European gas prices for the foreseeable future, meaning the landed cost will depend on Henry Hub pricing (the industry standard), plus the transport cost and margin. The scenarios we analyzed show that Germany is suffering significant competitive disadvantage against other regions, not only in the near term but also through 2030. (See Exhibit 1.)

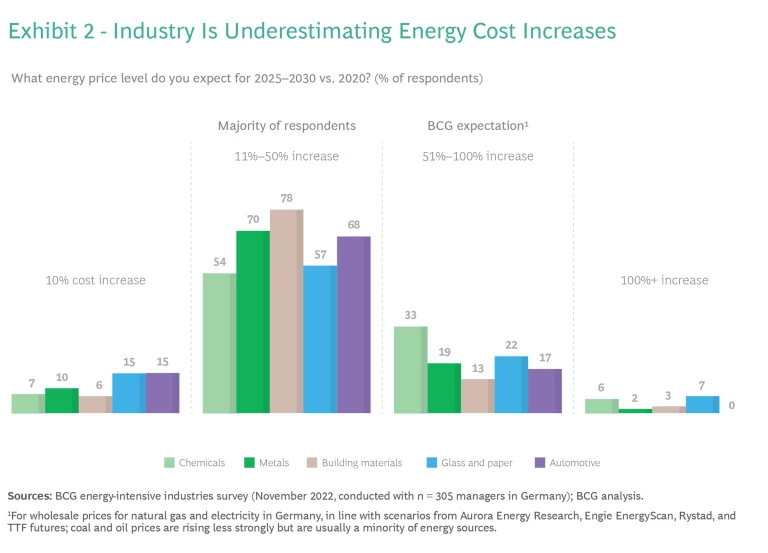

Industry, at least in Germany, appears to be underestimating the impact. While various energy and commodity scenarios point to an uplift of 50% to 100% in natural gas prices in 2030 (to €20 to €40/MWh), roughly one-half to three-quarters of our survey respondents expect increases of only 11% to 50%. (See Exhibit 2 and “The Outlook for Natural Gas in Europe.”) Furthermore, only 36% have started to implement forward-looking measures as a response to the energy crisis.

The Outlook for Natural Gas in Europe

The Outlook for Natural Gas in Europe

Natural gas at delivery now costs about €55/MWh. While this price is more than double the historical preinvasion average, fears of energy poverty and scarcity are much diminished. The EU is about to overdeliver on its 15% natural gas savings target this winter, having reduced consumption by 19% during the August 2022 to January 2023 period compared with the same months from 2017 to 2022. Contributing to this demand decrease were warmer weather, fuel switches and efficiency measures in buildings and industry, and significant production curtailments in energy-intensive industries such as chemicals.

European natural gas storage tanks in February 2023 were three-quarters full, well above historical norms. If trends hold, and if we experience similar weather conditions in the 2023 to 2024 winter season as in the winter just ended, the region will likely need a similar amount of LNG imports (or 511 mmcm/day). Demand should fall in the following years to about 501 mmcm/day. But Europe remains vulnerable to global price volatility: more than 70% of its LNG in 2022 was purchased on the spot market. The European supply situation still warrants caution (and a risk premium).

We do not expect a return of Russian supply. In January 2023, Russian gas accounted for 8% of all European gas imports, down from the prior year’s 26%. There are indications that Russia will again start honoring some natural gas commitments, but this will not raise volumes significantly. Known Russian LNG imports have increased for several European countries, but by an average of only 10 mmcm/day, a relatively insignificant volume given that piped volumes exceeded 300 mmcm/day before the run-up to the invasion.

The two biggest risks for Europe are the return of China to the LNG market as it reopens from its zero-COVID policies and simple complacency. Europe’s LNG imports in 2022 matched almost exactly the volumes that China would have been expected to import absent COVID-19. With China’s return, barring a global economic slowdown, competing for LNG may be more difficult this year even as European import capacity continues to rise. Improving conditions and receding fears of shortage in Europe could further push up demand, putting the region in a more precarious situation as it approaches the winter of 2023 and 2024.

In the electric-power generation market, which is subject to its own dynamics, natural gas demand is 28% higher since the beginning of 2023 compared with last year, driven largely by the changing pricing dynamics between natural gas and coal and the uncertainty surrounding French nuclear-power generation. To ensure a consistent and affordable supply of electricity, the European Commission in January 2023 started public consultation on electricity market reform. The goal is to better shield households and businesses from volatile prices while increasing market resilience and accelerating the supply of clean energy. Proposed key measures include the expansion of long-term contracts that provide power plants (both renewable and potentially nuclear energy) with a fixed price for their output, through mechanisms such as “contracts for difference,” power purchase agreements, and incentives for flexibility.

While improvements to the existing electricity market design are welcome and should help to “future proof” the system, they are unlikely by themselves to structurally bring wholesale prices back to precrisis levels, because power plants fueled by natural gas will continue to be an essential part of the generation mix.

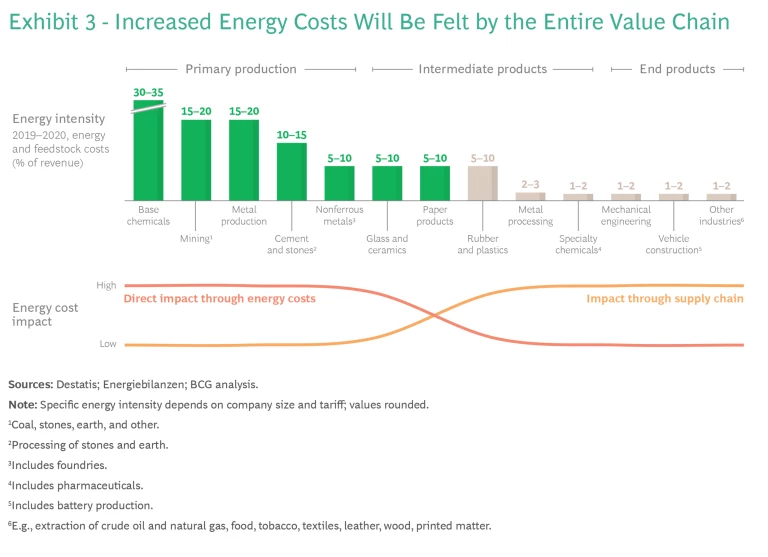

If the scenarios are right, the resulting energy price disadvantage will fundamentally alter the competitiveness of multiple major European industries. The impact will be felt along the entire value chain, from process industries to end products, either directly or indirectly. (See Exhibit 3.)

Adding further pressure, the US is expanding its current green energy cost advantage with implementation of the law known as the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), enacted in 2022. With a planned budget of almost $370 billion for clean-energy and green technologies—on top of the more than $110 billion in climate and energy funding included in the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act—the US is aggressively boosting industrial decarbonization and the formation of green markets. The IRA reduces the cost of renewable and green energies by up to 75% (for example, about 57% for onshore wind and 75% for green H2). By 2030, the improved economics will bolster US renewable deployment by four to six times today’s installed photovoltaic (solar) capacity and twice the wind capacity, accelerating the transition away from fossil fuels.

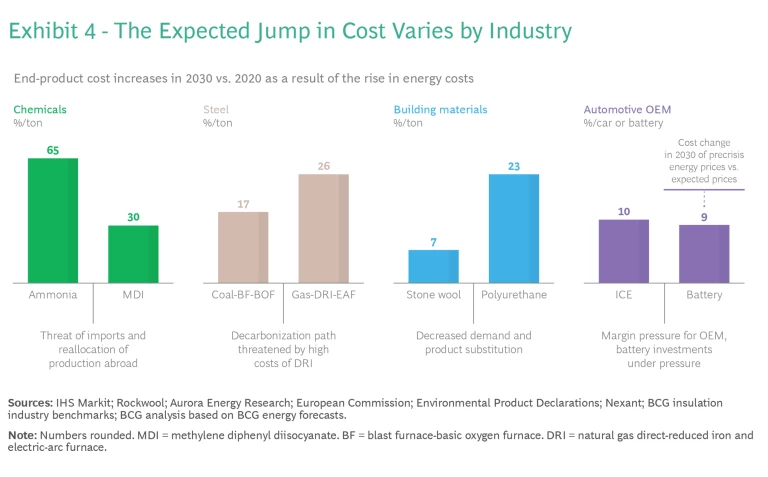

In contrast, the EU historically has emphasized demand-side incentives rather than supply-side subsidies, although recent US (and other) subsidies have triggered a reconsideration. The EU Green Deal Industrial Plan (GDIP), for example, is a package of proposals designed to accelerate decarbonization and compete for global investment. Still, all sectors in Europe face a structural loss in cost competitiveness from the significantly increased production costs (more than 10% in 2030 over 2020). The severity and implications differ depending on a variety of factors (such as energy mix and the flexibility of production and trade intensity). (See Exhibit 4.)

To assess the implications, we examined three of the most energy-intensive sectors of the German economy—chemicals, steel, and building materials—as well as the automotive sector to illustrate the effects along the value chain. Combined, the four sectors accounted for about 10% of German GDP and some 2 million jobs in 2020. We explore the details in “

The Price of Inaction for Four Key Industries

,” but here are the headlines:

- Chemicals. In the medium term (2025 and afterward), many petro- and base chemicals, especially those derived from natural gas, will face a shift in competitiveness. Whole value chains as well as the economics of steam cracking, a basic process for myriad products, are potentially at risk.

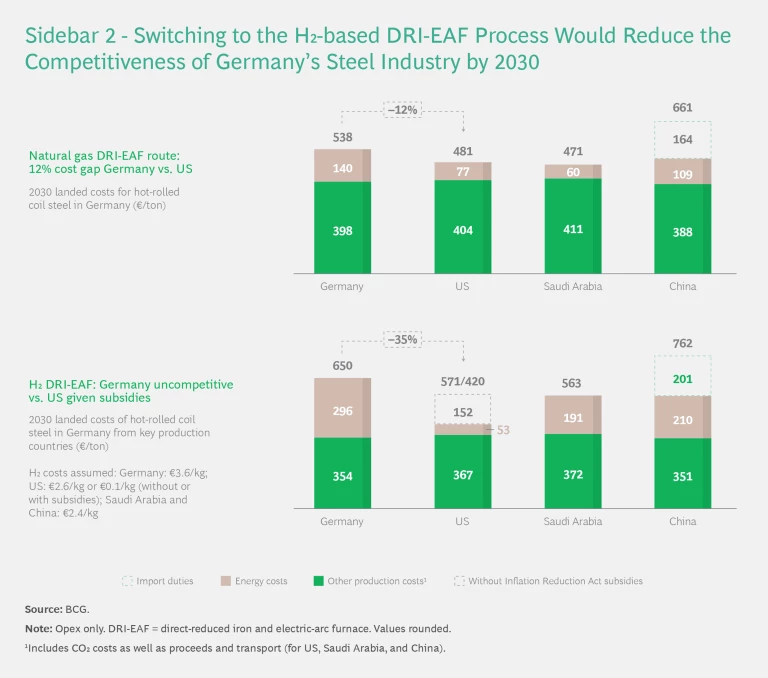

- Steel. Expected high natural-gas prices will lead to a cost differential of about 12% between Germany and the US, rendering German production uncompetitive against imports. Using H2 and direct-reduction production routes instead of natural gas would widen the cost disadvantage even further, to about 35% (because of IRA-subsidized H2 in the US).

- Building Materials. Elevated energy prices will increase the cost of goods sold (COGS) by up to 100%, depending on the energy intensity and energy mix used for each material. This will result in multiple structural changes to the industry.

- Automotive. Across the value chain, higher energy costs are expected to raise the price of a typical internal combustion engine (ICE) C-segment car by about €1,500 in 2030 over 2020. Many suppliers will struggle to compensate for high energy costs through cost reduction and efficiency measures alone. Since they also face other challenges, such as the availability of skilled labor, it is likely that some companies will shift production toward less expensive countries.

A Real Opportunity

The kind of measures that Europe has already taken can help mitigate the worst effects of the current crisis but cannot overcome the structural disadvantages relative to the US and China. Europe needs to relevel the playing field—and find new sources of competitive advantage.

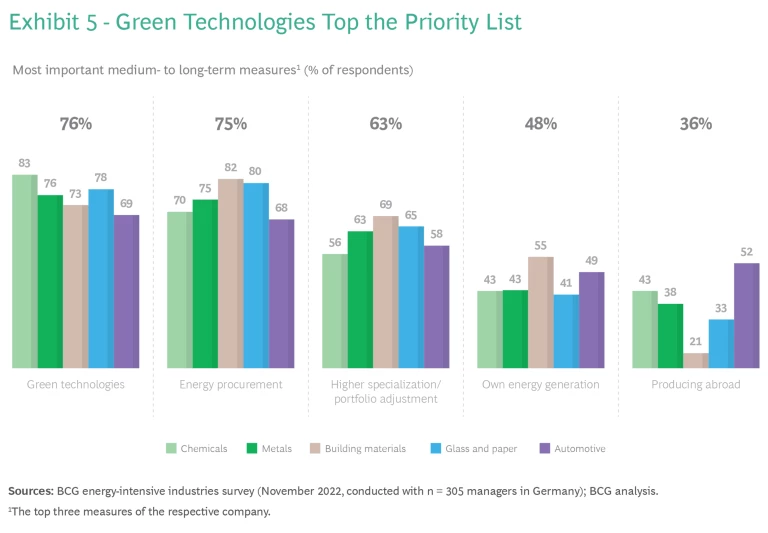

The obvious opportunities lie in green markets and green technologies, where Europe already has demonstrated capabilities. (See Exhibit 5.) Given the growing number of companies with ambitious supply chain emissions-reduction targets, there is significant emerging demand for green products, including non-fossil-fuel alternatives to chemicals, steel, aluminum, and other materials. According to a recent study by BCG and the World Economic Forum , for example, as of November 2022, 1,957 companies had set certified, science-based emissions-reduction targets, and a further 2,103 had committed to set them—a substantial increase in many sectors. At the same time, scarcity is likely to be an issue for some critical green inputs. There is a notable gap between the commitment of downstream players to decarbonize their upstream value chains and the commitment of upstream players to provide the low-carbon materials needed to meet these targets.

While most European players so far have a cost disadvantage in fossil fuels and feedstocks, the same is not true for renewable ones, at least not compared with the pre-IRA US and China. For companies that want to continue competing in Europe, the green transformation has turned from a growth opportunity into a strategic necessity. Even industries with heavy export footprints, such as energy equipment or assembled goods, have an opportunity to move earlier than others to establish new rules of competition, though green markets will not fully replace traditional ones.

For companies that want to continue competing in Europe, the green transformation has turned from a growth opportunity into a strategic necessity.

The Way Forward for Industry

To win in green markets, European companies need to take a leap of faith. A nascent market for green materials exists, but instead of waiting for the market to mature, companies need to develop it themselves. They should accelerate their own net-zero transformations and broaden their efforts from lowering emissions to commercializing sustainability by developing portfolios of green products, for consumers and other businesses. The good news is that our survey indicates most companies are already prioritizing green solutions.

Subscribe to our Industrial Goods E-Alert.

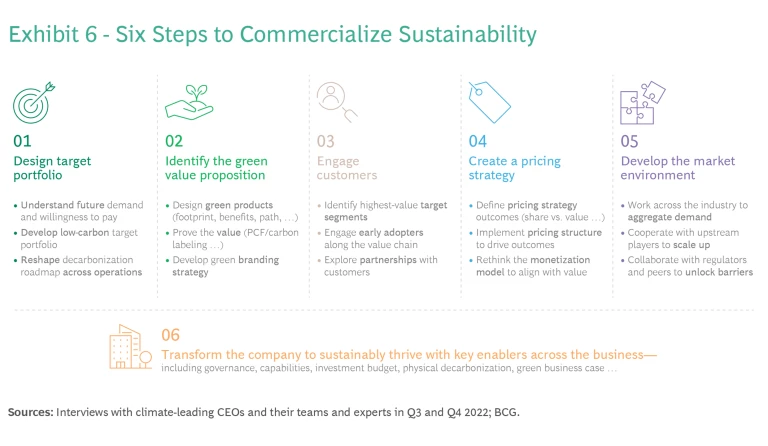

BCG and the World Economic Forum have set out a green go-to-market roadmap for commercializing sustainability. (See Exhibit 6.) It has six steps:

- Design a “green” (target) product portfolio. Start by investing in an understanding of future demand and customers’ willingness to pay more for sustainable products. For upstream players, this means assessing how low-carbon base materials can help target customers achieve their scope 3 decarbonization ambitions in the medium term. The same upstream product will have a different relative decarbonization value in different sectors. Downstream organizations should judge whether the demand for net-zero versions of their products could be mobilized once the products exist. In many cases, it could.

Identify the value proposition of green products. Upstream players will be able to commercialize a low-carbon offering only if it actually brings down their customers’ scope 3 emissions. Where possible, go beyond environmental dimensions (to health and usability, for example), which may increase a product’s value and compel customers to pay more.

When introducing a green product line, companies need to think about creating a green branding strategy. They should double down on emissions transparency by developing the ability to provide a product carbon footprint (PCF) for all major products. For example, BASF is working on the ability to make an auditable PCF available for all its products going forward. Steelmaker ArcelorMittal is an example of a company that has taken a portfolio approach to this challenge. It has developed a vision for a low-carbon target portfolio that balances interim products that decarbonize using physical and mass-balance approaches (such as its XCarb umbrella brand for reduced, low-, and zero-carbon steelmaking) with its long-term investments in developing truly nonfossil steel at the product level.

- Engage the most promising customer segments, especially early adopters. In several of the sectors we analyzed, downstream users face scarcity in upstream inputs and products. True nonfossil steel, for example, is available only from a single pilot plant in Sweden, whose product has sold out for years. The supply of nonfossil chemicals and plastics is marginal. Cement producers are still in the planning stages for carbon capture and storage projects to decarbonize their products. To translate customer ambition into actual buying behavior in the early stages of market development, companies will need to explore partnerships with customers. In many cases, these types of partnerships will be arranged outside traditional sales channels. In some cases, they might involve more than two companies. For example, when Maersk set out to pioneer green logistics, it partnered with green fuel providers, vessel engine manufacturers, and early offtakers such as H&M.

- Create a green pricing strategy. Whether upstream players can realize a price beyond “cost-plus” depends on market scarcity and their ability to produce low-carbon materials below market cost. Companies can also choose to price ahead of the curve to gain a share of new technology and secure an early-mover advantage on scale benefits. New monetization models may be necessary to align products with value. For many green product launches, traditional “make and sell” models will still apply. In other settings, circular models are gaining traction as companies consider the full life cycle emissions of a product. In recent years, this has given rise to an increasing number of subscription and pay-as-you-go schemes.

- Develop the market and break down barriers by forming partnerships with suppliers, customers, peers, and regulators. Upstream companies should seek support and cooperation from their downstream customers and other players to help scale up the market. In markets at risk of being short of supply, downstream users may be ready to invest in upstream solutions to create the net-zero products they need. For example, IKEA invested in RetourMatras to build mattress-recycling capacity and help develop new foam that is based on postconsumer recycled foam, enabling circularity. Collaborations upstream also help position these companies to be earlier to market with their own green transformations.

- Transform internally with new capabilities, structures, measures, and incentives. For many companies, succeeding in green markets requires not only a new go-to-market roadmap but also a broader transformation and mindset shift across their organization. This will necessitate new capabilities, incentives, and forms of internal collaboration across different business functions.

Policymakers Can Help

Europe’s policymakers at both the national and the EU levels should do everything they can to support industry’s transformation efforts. Creating green markets will require stronger transparency requirements. Accelerating demand may entail a willingness by government entities to buy green themselves—and create green markets through product standards and quotas.

The public sector should support nonfossil transformations financially—and with as little bureaucracy as possible.

The public sector also should support nonfossil transformations financially—and with as little bureaucracy as possible. Europe’s green policy schemes have traditionally been geared toward avoiding overspending. Some have been punitive instead of supportive. Many German policy schemes have been complex and underutilized. For example, only 0.4% of Germany’s relief fund for the 2021 flood disaster has been deployed.

Take another example: Germany’s Carbon Contracts for Difference (CCfD), a well-meaning initiative that supports green technologies but at a cost level that is now uncompetitive. CCfDs aim to support the transformation of energy-intensive industries as part of Germany’s goal of reaching climate neutrality by 2045. The new policy would compensate companies for the additional costs of green production processes compared with today’s more CO2-intensive ones. While the intention is commendable, unfortunately many in industry considered the draft policy, published in December 2022, to be overly complex and destined to create excessive bureaucratic burdens for both companies and the government. (See “The Price of Green Steel.”) The success of the CCfDs is now in question given the potentially low adoption rate by companies and uncertainty over the resulting cost competitiveness of German companies versus global players.

The Price of Green Steel

The Price of Green Steel

This current CCfD mechanism is supposed to be dynamic, adjusting the amount of subsidy to the achieved green premium and ETS proceeds. But it provides no incentive for producers to achieve the planned green price and unclear motivation for customers to pay the premium. Instead of incentivizing the creation of a green market, the subsidy and green price premium actually could find themselves in competition. Deployment of the CCfD mechanism will also require substantial data collection and administration; thus, adoption by the industry is questionable.

To achieve real step change, broader and simpler approaches focused on clearly defined outcomes are needed. Policymakers should concentrate on energy-intensive sectors critical to the wider economy (such as steel and chemicals) and provide them with easy-to-access (and potentially short-term) financial support. In parallel, policymakers should seek to incentivize demand for green products in downstream industries to help create green markets that are sustainable without subsidies.

Europe also can take lessons from the IRA in the US. The US policy may not be the most efficient means to create a green economy with public money, but it promises to be effective. In contrast, Europe’s policies seem very complex. The GDIP will build on the EU’s more established climate policy framework (including its emissions-trading system [ETS], Fit for 55, and REPowerEU) through regulation, finance, skills, and trade, including looser state aid rules and repurposing about €357 billion of existing funds to match US subsidies. Business leaders looking at green production investments are set to face (mostly) a positive but complicated and evolving environment that requires careful market comparisons across technologies and regions.

Winston Churchill famously admonished, “Never let a good crisis go to waste.” Europe’s situation is dire. But with war raging at its borders and imposing a historic challenge on its industrial competitiveness, European businesses and governments have an opportunity—and an obligation—to push a transformation that can secure prosperity for decades to come. They should not waste it.

The Price of Inaction for Four Key Industries

The Price of Inaction for Four Key Industries

Chemicals

The energy crisis hit the chemical industry particularly hard because of its dependency on oil and gas for energy and as a vital feedstock. Even prior to the crisis, big supply chain risks (such as disruptions in global logistics and price volatility) and the increasing pressure to decarbonize in a complex regulatory environment were significant industry challenges.

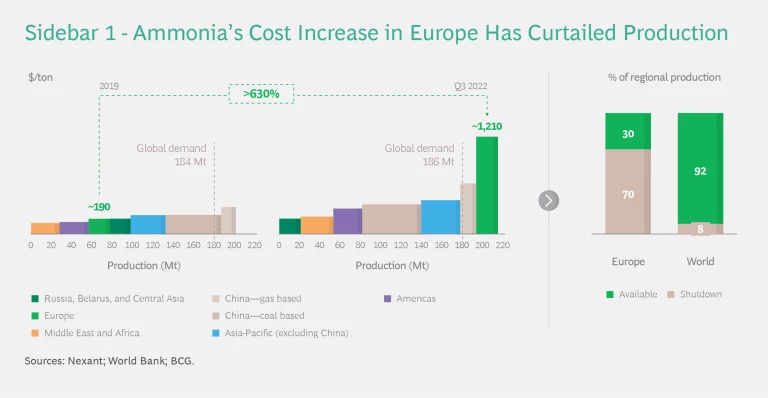

Now, decreased demand and a structural shift in competitiveness have severely exacerbated the situation and resulted in an unprecedented EU chemicals trade deficit of €5.6 billion in the first half of 2022. A prominent example is ammonia, which needs natural gas as a feedstock to produce hydrogen. Production costs in Europe skyrocketed more than 600% from 2019 to 2022, making it the most expensive production region in the world. In response, companies have drastically reduced or even stopped production, resulting in an overall curtailment of 70% of Europe’s capacity. (See “Ammonia’s Cost Increase in Europe Has Curtailed Production.”)

While easily traded chemicals are at the highest risk of replacement by imports from cost-advantaged countries (such as Middle Eastern nations), cuts in local production will resonate throughout the value chain. Reduced demand will challenge products upstream, and cost transfers or supply constraints will be issues for downstream products and specialty chemicals.

Overall, Europe’s chemical industry is facing a paradigm shift that will reshape its future depending on the actions taken now.

Steel

The steel industry has an essential position in Europe’s economy as a supplier to many other sectors, including automotive, engineering, and construction. At the same time, it is highly energy intensive and responsible for about 5% of the EU’s CO2 emissions. For the EU to reach climate neutrality in 2050, the steel industry must cut emissions, and pressure is increasing. The EU’s recent introduction of the Carbon Border Adjust Mechanism is one example.

About 60% of European steel is produced using the blast furnace and basic oxygen furnace (BF-BOF) process, with coal as the main energy source. While higher energy prices are expected to lead to a production cost increase of about 17% in 2030 versus precrisis levels, the cost differential with key competitive countries (China and the US) will remain relatively stable at about 30% and 5%, respectively.

More critical will be the impact of the energy crisis on the steel industry’s plan to decarbonize by gradually shifting toward a new production route, direct-reduced iron and electric-arc furnace, or DRI-EAF. This technology replaces coal with natural gas or H2, reducing the scope 1 CO2 emissions per ton of steel produced by 60% to 90%.

By 2030, Germany’s steel industry is aiming to produce about 35% of its steel via DRI-EAF. Expected high natural gas prices will lead to a cost gap of about 12% with the US, rendering German production uncompetitive against imports. Employing H2 instead of gas would widen the cost disadvantage even further, to about 35% when factoring in IRA-subsidized H2. (See “Switching to the H2-based DRI-EAF Process Would Reduce the Competitiveness of Germany’s Steel Industry by 2030.”)

Solving Europe’s challenge of decarbonizing the steel sector while preventing offshoring of production has become much harder and will require private and public investments as well as collaboration.

Building Materials

Building materials is one of the most energy-intensive industries in Europe, and elevated energy prices will increase COGS by up to 100%, depending on the energy intensity and energy mix used throughout the value chain of the respective material. This will result in three key structural changes, to a historically very local and rather static industry.

A Structural Dampening of Demand. Building projects are already being postponed because the volatility in building-materials prices makes it difficult to plan for construction costs. In the medium to long term, building-materials cost increases will accelerate existing trends such as the shift from single-family to more affordable multifamily homes and the move toward smaller dwelling sizes in the new-build residential segment. These changes will bring a structural decline in the demand for traditional building materials such as blocks, bricks, and tiles.

Substitutions for Energy-Intensive Materials. Building materials with a disproportionately high exposure to rising energy costs are likely to lose market share in the longer term. For example, polyurethane insulation foam, which depends on natural gas, will face a structural COGS increase of 30% to 60% over precrisis levels. Stone wool, on the other hand, which is typically produced using coal, will feel a lower impact from energy and carbon costs (a 10% to 30% increase in COGS by 2025). As a result, stone wool can be expected to gain share from PUR in substitutable flat-roof insulation.

A Shift in the Relative Competitiveness of Players. The surge in energy costs has altered the competitive cost positions of individual companies. Players that have a favorable fuel mix, an energy-efficient production process, or advantageous long-term energy-purchasing contracts will benefit from the current situation. Moreover, the energy cost differential between countries will result in additional cross-border trade, boosting imports to a traditionally local business. For example, glass-wool imports to Germany increased by 50% in 2022 over 2020, while exports decreased by 20%.

Automotive

The automotive sector accounted for about 7% of Europe’s GDP and some 13 million jobs in 2022. While energy costs make up only 3% or less of car costs, automobile production requires energy-intensive materials such as steel, aluminum, and other metals. As energy costs increase across the value chain, they will squeeze OEM margins, and manufacturers will be forced to either pass on rising costs to the consumer or demand lower costs from suppliers. Many suppliers will struggle to compensate for high energy costs through cost reduction and efficiency measures alone. It is likely that they will accelerate production shifts to lower-cost countries.

Electric vehicles present a slightly different picture. The energy costs of a typical C-segment car are expected to rise by approximately €1,300 (across the full value chain). Despite this increase, EV prices are likely to drop over time until about 2030 because of growing production efficiency, supply, and scaling effects. Battery costs will play a key role in this drop, as they account for almost 25% of an EV’s price today.

Battery production itself is energy intensive (largely because of mining and material production) and mostly done in China. Europe’s plans to ramp up production to provide more than 1600 GWh cell capacity by 2030 are threatened by high energy prices and the US IRA. For example, Northvolt, a Swedish battery maker, is now assessing whether to go ahead with the construction of a plant in Germany or prioritize expansion in the US. Other companies have similar considerations, causing Europe’s EV makers to urge the EU for a strong response to the IRA.