The energy transition is an historic pivot from an insatiable thirst for oil to a soaring reliance on minerals. Lithium, cobalt, and the so-called rare-earth elements (or rare earths), among other metals, are essential in the production of most green devices and equipment, including electric vehicles, windmills, and solar panels. These minerals will therefore be needed in huge volumes to meet aggressive global carbon-emissions targets by 2050. But as mineral demand rises to levels beyond any seen before, supply shortfalls are looming. In particular, an alarming shortage of rare earths is impending.

Fearing potentially large capacity gaps, mining industry players are revisiting rare-earth mining practices and strategies. At the same time, many inside and outside the industry are exploring pressing questions: What will it take to have enough capacity to meet forecasted demand? How are today’s opportunities, which stem from lagging supplies, shaping the future of the industry? What does winning look like in this environment? What role should government play to ensure the availability of minerals necessary for the energy transition? How will shortages define the geopolitics of mining?

At the heart of the impending rare-earth deficit is yet another illustration of what is known as the tragedy of the horizon: a significant problem that today’s leaders show little urgency to address because its impact will mostly be felt by future generations. In this case, the dire outcome of a rare-earth shortage—worsening climate change—is given short shrift, in large part because rare-earth projects seemingly fail to meet the short-term financial-return objectives of investors. Meanwhile, governments are of little help because they often lack the political will or the policy savvy to jump-start these difficult mining operations, despite rare earths’ potential contribution to meeting climate change objectives. To be fair, though, some of the hesitancy to back mining projects is because of environmental concerns about the projects themselves.

The Depth of the Shortfall

Rare-earth elements are so named only because it is difficult to find them in a pure form, but there are untapped deposits all over the world. Together, rare earths comprise 17 different metals, but four—neodymium, praseodymium, dysprosium, and terbium—account for about 90% of the market value of rare earths. These are the so-called magnet rare-earth elements, which are essential to produce the high-performance permanent magnets that are used in electric vehicles and wind turbines, as well as in more everyday items, such as hard drives and smartphones. Given that orders from automotive and wind energy companies are accelerating, the global demand for magnet rare earths is expected to reach 466 kilotons by 2035, up from 170 kilotons in 2022, a threefold increase that amounts to an 8% compound annual growth rate.

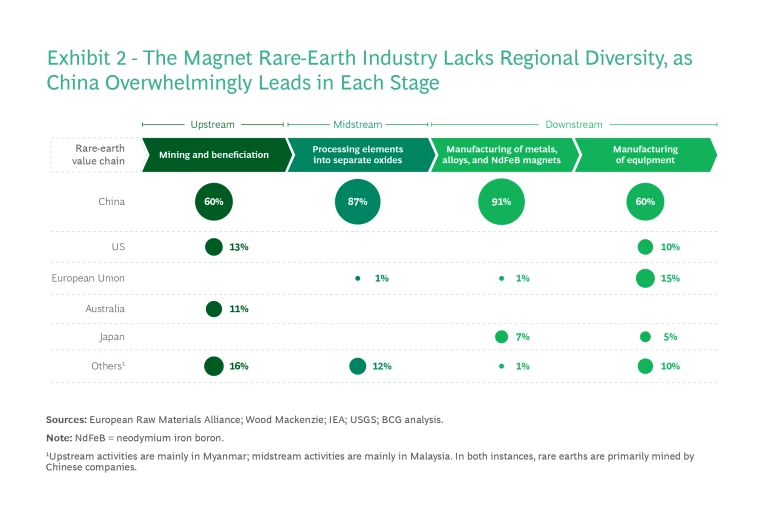

The rare-earth industry can be divided into three stages: upstream, or the mining of elements; midstream, the processing of elements into separate oxides; and downstream, the manufacturing of permanent magnets and other components made with rare earths.

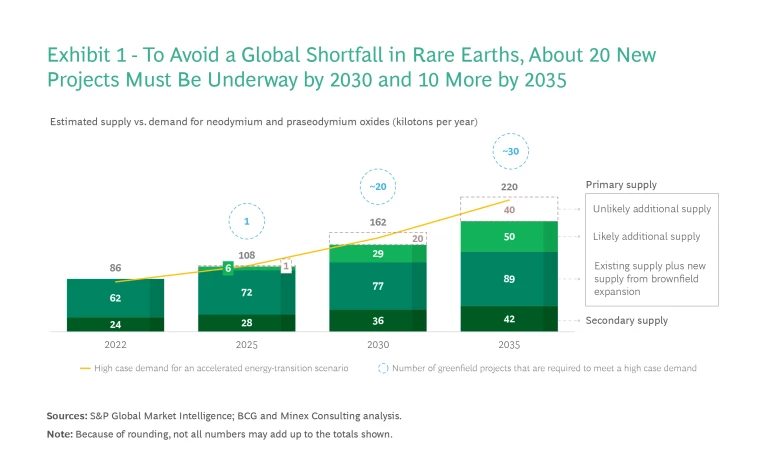

Making rare earths globally available starts in the upstream stage. To avoid a shortage of rare earths by 2030, more than 20 new rare-earth projects would need to be launched between now and then, with an additional 10 projects needed by 2035. (See Exhibit 1.)

We arrived at this conclusion after examining the likely output of 30 large, credible projects that have been proposed or that are underway. (See the sidebar “Analyzing Rare-Earth Projects.”) We found that even these projects will fall short of meeting demand by the end of the decade. This is because most are just completing their feasibility studies and have not yet secured funding, which is proving difficult given current market conditions. And even the projects that will be eventually greenlighted are still seven to ten years from beginning their development. In addition to these 30 significant rare-earth projects, hundreds of small-to-midsize projects are in various stages of planning or construction. But many of them will not produce the required ore grade and magnet rare-earth content to be viable for the largest demand pools.

Analyzing Rare-Earth Projects

We then assessed each project’s likelihood through a series of interviews with BCG and non-BCG experts, and a systematic analysis of such criteria as competitiveness, development stage, and the ability to obtain funding.

We also assigned probabilities according to projects’ likelihood (80% for probable projects, 50% for potential projects, and 30% for the least-probable ones) to come up with a probability-weighted total rare-earth capacity output from these projects: a likely additional supply as well as an unlikely additional supply. We determined the timeline for ramping up capacity output by the current development stage of each project and a set of assumptions about the duration of each step of the process (for example, three years for construction, two years to secure funding and commercial agreements, one-and-a-half to three years to complete feasibility studies, one year to complete scoping and prefeasibility studies, and one-and-a-half years for advanced exploration and reserve development).

At this point, the rare-earth project landscape is constrained by a lack of regional diversity—and looking at the potential upcoming projects, this situation doesn’t appear likely to change. (See Exhibit 2.) Currently, from upstream to downstream, most of these projects are in China; indeed, only two non-Chinese companies—MP Materials in the US and Lynas Rare Earths in Australia—are active players in the upstream stage. But their current mining capacity and recoverable reserves are too limited to match expected demand growth outside of China.

Rare-Earth Market Challenges

As the need grows for permanent magnets to support energy transition technologies and other critical uses, including defense systems, countries will seek to develop rare-earth supply chains either domestically or through international alliances that can be sheltered from geopolitical dynamics. Indeed, it is increasingly clear that more and more nations and regional powers view access to rare earths to be a matter of domestic economic and national security. But to establish these supply chains, a series of barriers must be overcome, including technical and revenue obstacles, as well as capital shortfalls.

Technical and Revenue Obstacles. The biggest technical challenges involve midstream and downstream activities. In the midstream stage, creating a pure oxide form of each rare-earth element is extremely complex and time consuming, because each element has to be separated from surrounding materials and from other elements that have similar chemical properties. Upskilling or recruiting staff who are already capable in midstream activities can be expensive and only incrementally successful, which is why only two non-Chinese companies have been willing to try to make inroads into the processing market.

In the downstream stage, Japan’s Hitachi and certain Chinese producers dominate the manufacturing of permanent magnets. Their advanced patented technologies give them a significant competitive edge, effectively occupying about 90% of the permanent magnet market, leaving the rest available to a handful of small international companies.

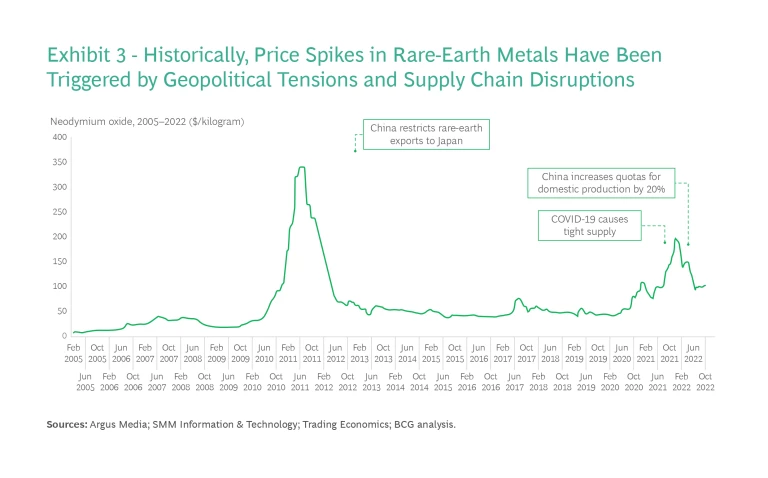

The extent of these technical issues—and the amount of effort and resources required to overcome them—has deterred investments in rare-earth projects, particularly as prices for the elements have consistently failed to rise above the breakeven target for mining them. For instance, neodymium oxide would have to be priced at roughly $150 per kilogram for a midstream project to be profitable. Yet, over the past decade, neodymium oxide has never exceeded this threshold for any significant period. (See Exhibit 3.)

Looking ahead, it is likely that neodymium oxide prices will more often settle above the breakeven threshold as demand for permanent magnets rises. But at the same time, significant questions remain about how the market will evolve. For instance, prices could be depressed by the lower-than-expected growth of electric vehicle sales and market penetration of wind power or by technology shifts that reduce the use of permanent magnets. In addition, rare-earth project returns could be weakened by bottlenecks that occur in the rare-earth supply chain. For example, if midstream and downstream capacity to absorb upstream flows is not addressed quickly enough, revenue at every level of rare-earth development will suffer.

Given the uncertainties surrounding the viability and potential returns of rare-earth projects, the major mining players have generally avoided these efforts. Instead, the bulk of development outside China is led by smaller companies, with less financial and technical capacity. Having limited resources explains why most of the 30 sizable potential projects that we examined have been put on hold at the prefeasibility stage.

Capital Shortfalls. Currently, there are few signs that larger asset investors and mining companies will overcome their risk aversion and tilt their funding strategies toward rare-earth ventures. Capital for less attractive projects is getting tighter in a period of rising interest rates and global economic uncertainty. Also, some top-tier investors are increasingly wary of backing projects with potentially problematic environmental footprints. Rare-earth projects use large quantities of water, placing significant pressure on local resources, and many have historically been designed with few environmental guardrails.

Offering incentives to improve midstream and downstream capacities won’t increase the volume of rare earths quickly enough.

By our reckoning, from 2022 through 2035, about $100 billion in investments in the rare-earth value chain will be needed to keep pace with demand, particularly for the four magnet elements. The upstream stage alone may require as much as $30 billion. However, currently planned and committed investments for new or ongoing projects stand at roughly $5 billion. In addition, many of the capital incentives that are being offered by policymakers for rare-earth projects target improving midstream and downstream capacities, hoping that this will jump-start upstream projects. But that approach will be too slow to sufficiently increase the volume of rare earths.

Five Steps to an Efficient Market

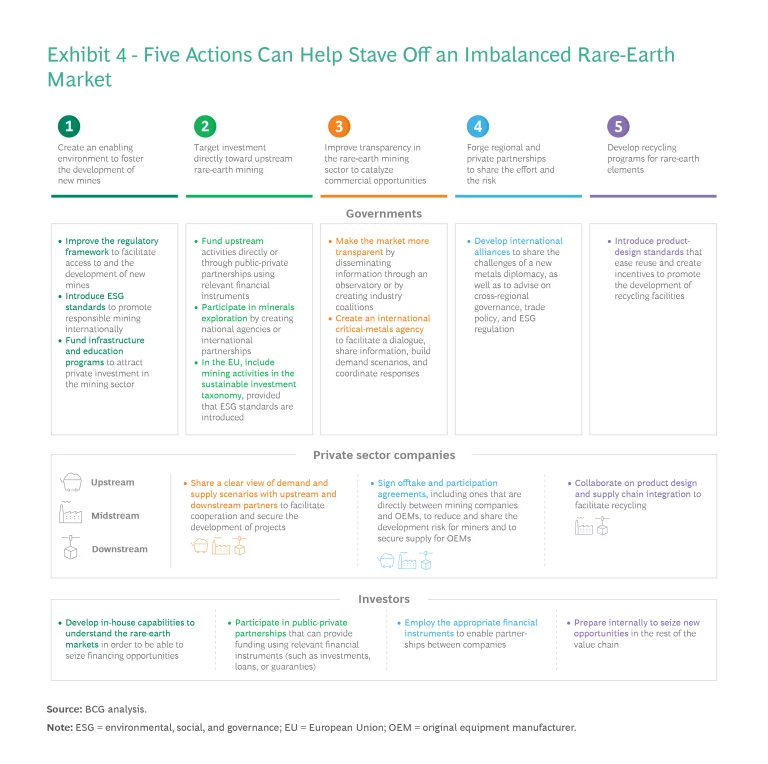

Addressing the challenges and developing a thriving rare-earth marketplace outside of China will require a diligent, coordinated effort among government entities, investors, and the private sector. For this joint effort to succeed, stakeholders may have to make decisions that go beyond pure economic logic and address strategic and environmentally sound needs.

Five actions should be taken immediately to stave off an impending and troubling supply and demand imbalance. Governments will initially have to play the most prominent role, because rightsizing the rare-earth market will not occur naturally—that is, without regulations, policies, and financing from the public sector. Indeed, governments have a vested interest in making sure that domestic rare-earth projects are well supported whenever possible, chiefly to minimize their nation’s dependence on foreign countries for these critical minerals, which are about to become even more valuable. But the private sector will quickly have to show leadership for the global market to develop in a coherent fashion. (See Exhibit 4.)

Create enabling conditions to foster the development of new mines. To varying degrees, governments are already taking action. For instance, the US, through the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 and other measures, is offering fiscal incentives, such as tax credits, to develop domestic supply chains of critical minerals. However, these incentives are primarily directed toward midstream and downstream operations—those that manufacture made-in-USA permanent magnets and electric vehicle equipment, for example. That approach leaves open the possibility of having to continue to source rare-earth ore abroad, which may stymie attempts to create an integrated supply chain in the US.

For its part, Canada is focusing on its regulatory framework in the upstream area. The government recently pledged to review the permit process for rare-earth mines so as to reduce the time it takes for companies to get approval to operate. Among the key aspects of this effort would be seeking the consent of indigenous peoples early—when a company is proposing to mine rare earths in a community. The Canadian government has set aside as much as $3 billion to facilitate and support new mine applications and development.

In emerging regions such as Africa, it is crucial for governments to take similar actions. While Africa has significant amounts of critical minerals, it is the second-least-attractive region for mining investment (after Asia) because of a multitude of local policies and rules that can make it very difficult to get projects off the ground. African governments should take steps to create a better environment for new exploration and investment in downstream operations by designing consistent rules for the mineral-rights application process that cannot be easily confounded by local bureaucracies. For example, there have been instances of local authorities rescinding mining permits well after projects were underway and millions of dollars were spent. In addition, considering the global need for rare-earth reserves, African governments could seek support from international agencies for geo-mapping remote areas to uncover potentially viable locations for mining.

In Europe, new mining projects must undergo increasingly extensive environmental impact assessments. However, for rare-earth production to be widely adopted in these and other developed economies, governments should implement regulatory frameworks that guarantee minimal environmental impact to overcome local populations’ opposition to mining. Techniques that minimize damage to the environment include using a renewable source for onsite energy, implementing water recycling and reclamation, and strictly containing and disposing of toxic waste, such as the tailings from rare-earth extraction.

Finally, governments will have to invest in education and training to develop workforces with the high level of geological and chemical processing skills and expertise necessary for rare-earth projects. Funding for infrastructure improvements—building reliable roads, constructing power grids, and sourcing energy—is also essential.

Target investments directly toward upstream rare-earth mining. Because of long lead times—up to five years—to develop a rare-earth mine, upstream operations should be initiated immediately. China, of course, has a robust rare-earth sector, but in Europe and North America, progress toward upstream mining has been slow. For its part, the European Union recently put forward a set of actions under the Critical Raw Materials Act that would accelerate critical mining activities in the EU. Under the proposed rules, at least 10% of the EU’s annual consumption of critical raw materials would be met by domestic extraction, and “not more than 65% of the Union’s annual consumption of each strategic raw material at any relevant stage of processing [could come] from a single third country.”

While that legislation may close the rare-earth supply gap a bit, EU financing regulations that govern the types of projects that can be called environmentally friendly do not help because they omit mining. As a result, green investors will be reluctant to put their money in rare-earth efforts, even though it is essential for EU countries to open new mines to source rare earths for the wind turbines and electric vehicles that are required for the EU’s energy transition ambitions.

Quasi-government and multilateral entities could use their lending arms to provide investments, loans, or guaranties to new projects.

Public-private partnerships could be perfect vehicles for funding rare-earth mines. Quasi- government and multilateral entities—including development banks (such as the IFC and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development) and development agencies (such as the German Agency for International Cooperation)—could use their lending arms to provide investments, loans, or guaranties to new projects.

Perhaps the most effective example of a public-private partnership took place in Japan in 2010 when a political dispute with China threatened Japan’s supply of rare earths. To protect against this potential shortfall, the Japan Organization for Metals and Energy Security, an independent administrative unit of the government, extended a low-interest loan to Australia’s Lynas Rare Earths, which was relatively new in rare-earth mining at the time. Within three years, Lynas had overcome technical problems and was routinely producing rare-earth metals in its Malaysian facility. This financial agreement effectively helped Japan to shore up its supply of rare earths.

Improve transparency in the rare-earth mining sector to catalyze commercial opportunities. The recently created French Observatory of Mineral Resources for Industrial Sectors is a public-private group charged with developing technical, economic, and strategic analyses pertaining to critical raw materials. These assessments are intended to provide various levels of the French government and organizations in the industrial sector with sufficient information to make decisions, including ones about planning new mining ventures and adjusting supply and demand.

Similar ventures are needed in other global economies. By collaborating, members in a public-private group could monitor and chart both the production of critical-mineral projects at various stages of development and the downstream companies that may buy the elements. Members could also match possible commercial partners to codevelop mining projects, create communities for knowledge sharing, and encourage research and development in best practices, including ones for environmentally sound approaches. In addition, members could draw up business models and strategies and lay out roadmaps for investing in rare-earth mines.

At the international level, global economies should create a multilateral agency like the International Energy Agency. Focused on critical raw materials, the agency would create more global transparency about supply and demand, the status of new and existing projects, and supply chain effectiveness.

Governments and public-private consortia should spawn regional alliances to ensure global cooperation and share risk.

Forge regional and private partnerships to share the effort and the risk. There is only so much that countries can do alone. It is important for governments and public-private consortia to spawn regional alliances to support rare-earth sector growth, ensure global cooperation, and share risk. For instance, a multinational consortium could establish a mine in Australia, processing capabilities in Europe, and downstream production in the US—with financing and output equally divided among the participants. Such a broad alliance could collaborate in setting goals for the project’s environmental benchmarks, inter-regional trade, and sharing R&D and market expertise—all facets that need to be standardized globally to expand activity and performance in the rare-earth sector.

Companies can create individual partnerships as well. Downstream companies need to be certain that they have reliable rare-earth supplies to manufacture their components, and upstream players must be assured of outlets for their mining output. Locking in critical-metal sources now, even before demand has evolved but anticipating future market growth, would boost new mining projects and close the supply gap that will otherwise develop over the next decade. For example, General Motors and General Electric have a joint arrangement to purchase rare earths in the coming years from Australia’s Arafura Rare Earths. Despite this agreement, both GM and GE do not yet have capabilities to create permanent magnets from the metals, but they want to assure supply availability for strategic initiatives pivotal to their growth.

Subscribe to our Industrial Goods E-Alert.

Develop recycling programs for rare-earth elements. Creating reuse programs for rare earths in end-of-life products is imperative. Recycling can increase the amount of rare earths available for manufacturing permanent magnets and create a new source of supply of these scarce commodities. Currently, there are no at-scale recycling programs that separate out rare-earth metals, although some IT equipment, large appliances, and electric vehicle components with permanent magnets are repurposed.

To make sure that the rare earths are isolated and recycled, governments need to establish standards to ensure that manufacturers design their products to facilitate reuse. Governments also need to create incentives to trigger investments in recycling facilities. Rare-earth recycling is in its early stages, and financial support or tax deductions will be needed to encourage companies to get into an energy-intensive and, therefore, costly endeavor with only limited amounts of minerals available for recycling. The incentives would ideally catalyze collaboration among midstream and downstream rare-earth players to develop the recycling market in a way that builds efficiency into the process; reduces costs for both the recycler purchasing the end-of-life products and the manufacturer buying the recycled minerals; and allows for a pricing structure that generates consistent profits.

It is unrealistic to think that the development of downstream rare-earth demand alone will drive ample growth in upstream capacity. To close the supply gap, aggressive and purposeful action will be necessary. In particular, governments will have to show leadership and provide sufficient support to kick-start desperately needed rare-earth initiatives—and, in turn, public-private coalitions involving all parts of the value chain must more aggressively develop new projects and accelerate existing ones. The rare-earth shortage may not be uppermost in people’s minds now, but it must be resolved—or it will become a bottleneck, significantly limiting the world’s chances to meet its carbon emissions goals.