As electric vehicles come to dominate the global car market, profitable growth for the industry’s suppliers will depend on refocusing their parts portfolios.

The tier-one suppliers to the auto industry are in a bind. The industry as a whole is facing massive changes that are already transforming the nature of the automobile and how every player does business. The shifts taking place now—to shared on-demand mobility , the connected car, battery-electric vehicles (BEVs), and, eventually, the autonomous vehicle (AV)—offer both the potential to disrupt players throughout the industry and a path to real growth and profitability.

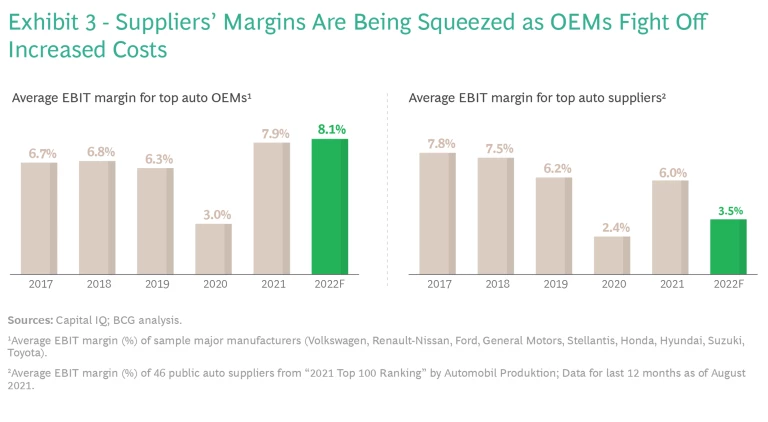

But the industry’s tier-one suppliers, in particular, are facing significant headwinds that threaten to keep them from participating profitably in this transformation. Production volatility among OEMs, supply chain disruptions, inflation, labor bottlenecks, geopolitical dynamics, and the ongoing redistribution of value across the industry value chain—all have increased suppliers’ costs, which they haven’t been able pass on to OEMs in full. As a result, while OEMs experienced record margins in 2021, suppliers’ 2021 margins, while higher than in the previous two years, are substantially lower than they were prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

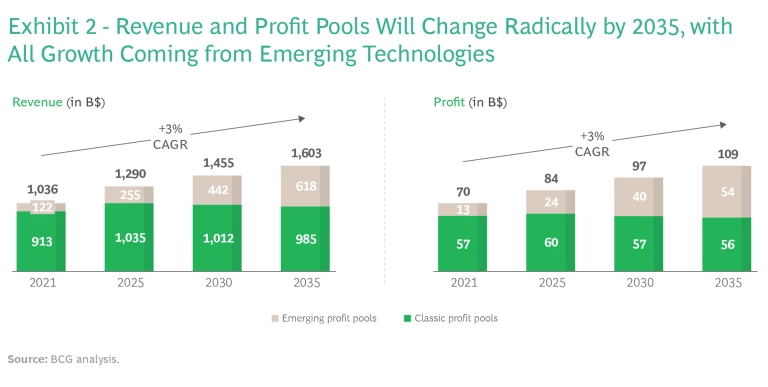

Looking forward, as the trends transforming the industry take hold, growth in suppliers’ revenues and profits must come increasingly from the systems and components needed for the next generation of vehicles, as revenues from classic components stagnate and profits decline. Under these conditions, a standstill strategy is hardly an option—but neither is growth without profitability.

Growth in supplier revenue and profit must come increasingly from systems and components needed for the next generation of vehicles.

To remain in the game, suppliers must decide on a path forward. One option is to develop and execute a carefully crafted portfolio strategy that meets the changing needs and sourcing strategies of OEMs while ensuring profitable growth. The other is to actively pursue a strategy to thrive in the remaining profitable pockets of the fading market for internal combustion-powered cars. The future for companies that fail to adapt as the roads fill up with electric and autonomous vehicles is grim.

The Challenge

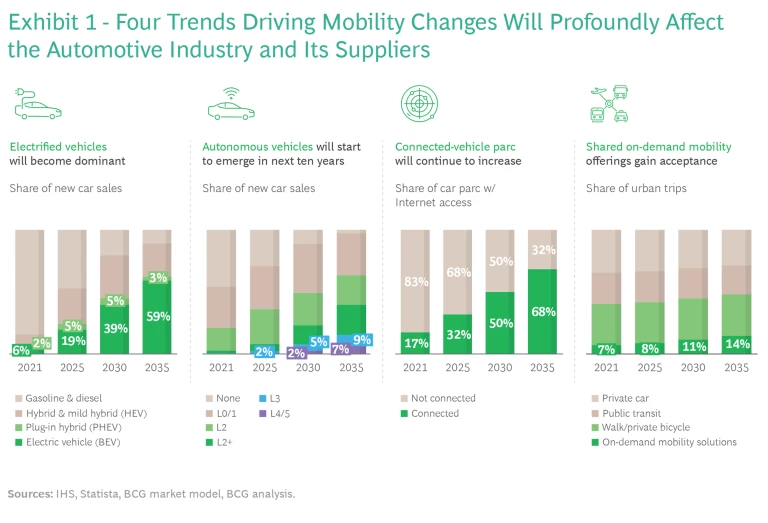

The writing is on the wall for the global auto industry. By 2035, the industry will look very different than it does today. BEVs will dominate, making up around 60% of new car sales. Internet-connected vehicles will make up 70% of the car parc around the world. The share of urban trips in on-demand vehicles will rise to 14%. And Levels 3 and 4/5 autonomous vehicles will account for 16% of all cars sold globally. (See Exhibit 1.)

As these changes take hold, virtually all growth in suppliers’ OEM-related revenues and profits will come from components and software for emerging technologies, including BEVs, AVs, and connected cars, while revenues and profits from traditionally powered vehicles will effectively stagnate. (See Exhibit 2). The impact on the aftermarket for traditional components will be less dramatic in the mid-term, but by the end of the decade, this market too will stagnate.

The growth in the emerging profit pools will be driven by two key areas: software (from $10 billion in 2021 to $26 billion in 2035) and electric powertrains (from $3 billion in 2021 to $22 billion in 2035). The flat performance of the “classic” profit pool will be determined by a dramatic decrease in internal combustion engine (ICE) powertrain components (from $19 billion in 2021 to $7 billion in 2035). Profits for trend-agnostic parts (interior, exterior) will grow moderately; exterior parts, for example, will grow from $12 billion in 2021 to $16 billion in 2035.

Headwinds

The shift in revenue and profit pools presents a major opportunity for tier-one suppliers ready and willing to make the necessary changes to how they do business. Many suppliers, however, currently face a variety of challenges that are increasing production costs and significantly affecting margins. Those determined to take advantage of the new sources of value in the auto industry must manage through these challenges and set the strategic stage for future success.

Among the challenges, OEMs are facing unpredictability and constraints that continue to impact the accuracy of their demand forecasting, leading to swings in their production volume. Fluctuations in the availability of electrical and electronic parts, shipping delays, and rising costs continue to disrupt supply chains and create delivery delays. Cost increases in raw materials, labor, and energy are also compressing tier-one margins, as are bottlenecks in labor markets as the demand for skilled workers outpaces supply and employee expectations shift.

At the same time, value is being redistributed across the value chain as OEMs avoid absorbing suppliers’ rising costs. As a result, as Exhibit 3 shows, OEMs have recovered nicely since the pandemic, but suppliers’ margins have remained substantially below their pre-pandemic levels.

The impact can be seen in suppliers’ share prices, too, which since 2017 have underperformed both OEMs and the wider S&P 500, and adversely affected their total shareholder returns (TSR). As a group, an index of the suppliers’ TSR has been negative over the period, and fallen 40% below the S&P Auto index; only the top performers have made gains.

Yet suppliers looking to benefit from the trends impacting the auto industry must also understand that growth for growth’s sake is not the answer. There has been a strong correlation between TSR and revenue growth across the S&P 500 over time. But growth that actually creates value is hard to get right, and investors have begun to resist the notion of revenue growth “at all costs.” Given the current uncertain macroeconomic environment, investors in tier-one suppliers will likely look increasingly for short-term certainty in terms of profitability and cashflow.

Taken together, the transformation of the auto industry—and the struggles faced by suppliers—suggest that they need a new strategy, one that mixes profitability with sustainable growth. Given the coming changes in the types of components needed by OEMs, the answer for most suppliers lies in segmenting their business into product groups, each with their own strategies and growth expectations. Doing so will allow them to manage the transition to the new auto industry with far greater assurance, while playing to their strongest capabilities.

New Strategies

Suppliers looking to formulate a successful portfolio strategy should begin with a careful review of their existing product groups, broadly allocated to three segments based on their growth and profitability outlooks.

- Booster parts. The major source of growth, this category includes such trend-driven parts as advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS), battery management systems (BMS), and fuel cells. These parts offer generally greater profitability, though profits will depend on the specific niche—higher for software, lower for increasingly commoditized segments like power electronics.

- Carry-over parts. These include a range of parts that will be predominantly trend-agnostic and stable, such as exterior parts, HVAC, seating, lighting, and the like. Profitability for this category will generally be stable.

- Legacy parts. These include ICE engine systems and conventional transmissions, exhaust systems, fuel systems, and older generations of electronics and human-machine interface (HMI) systems no longer applicable for connected cars—all of which are generally declining as a result of trends in mobility. In general, future profitability for this category of parts will be declining as suppliers struggle with overcapacity.

Many tier-one suppliers will likely offer a mix of all three types of products. A proper portfolio strategy, however, will require the development of a separate, distinct strategy for managing each product group.

To create a successful portfolio strategy, suppliers should carefully review their booster, carry-over, and legacy parts product groups.

Booster and carry-over parts

Suppliers looking to benefit from OEMs’ shift to EVs and AVs need to carefully choose the areas in which to participate. Suppliers need to consider three factors in determining which parts and components businesses to pursue.

- Viability. Does the company have a “right to play” in the business? Issues to consider include the size of the market opportunity, sustainability of the business given key product trends, factors that provide competitive advantage, and the nature of the competition.

- Feasibility. How possible is the opportunity? Factors here include the nature of the value chain and the sourcing decisions that must be made, the opportunity’s high-level economics and profit potential, the ecosystem of potential partners, and key technological capabilities needed.

- Access. What is the pathway forward? Consider the entry strategy, including potential M&A targets and partnership and joint venture candidates, and develop an investment case, including an estimate of the required investment and potential returns.

Finally, as suppliers develop their strategy for entering the booster parts market, they must also take into account how OEMs’ own sourcing strategies are changing in the face of the major shifts occurring in the auto industry. Already, OEMs are coming to view their electric powertrains as a competitive edge and are now developing the capabilities and in-house expertise to maintain that edge. To that end, the share of insourced powertrain components will likely increase to compensate for the shift away from ICE. At the same time, they will seek to start working together on the development of joint BEV platforms to increase scale and drive down costs.

Meanwhile, in light of semiconductor supply chain disruptions caused by the pandemic and other factors, OEMs will be pushing to diversify and localize their supplier base. Sustainability, including the incorporation of greenhouse gas emissions criteria, will also become a factor in sourcing decisions, as OEMs look to decarbonize their upstream supply chains.

Legacy parts

Despite the inevitable long-term decline in the business of making parts and systems for ICE-powered vehicles, including older generations of electronics and HMIs, suppliers have several levers they can pull—both “no-regret” moves and strategic options—to maximize the value of this aspect of their portfolio.

All suppliers should consider making several “no-regret” moves to boost the current value of their legacy operations. Given the currently challenging cost environment, they should first reconsider their pricing policies, revisiting their commercial terms with OEMs and lifting prices. They also should manage their legacy operations to generate free cash through cost reductions and optimized working capital, then use the cash to bankroll their portfolio migration to booster and carry-over parts.

Even as they manage their legacy parts business for cash, they should consider several strategic options. First, they should develop a portfolio migration strategy, identifying potential target product groups in booster parts, then repurposing their assets and talent from the legacy business to the new areas. CAPEX and investments in talent must also be shifted to strengthen the new booster venture.

One way of maximizing the value of legacy parts for as long as possible is to pursue a “last person standing” strategy. This involves becoming one of the very few sources for a specific legacy parts segment and maximizing its revenues and profitability by reducing costs and rolling up similar businesses to increase scale. By entering adjacent product groups, suppliers can further reduce indirect fixed costs and drive synergies. (See “Built to Last.”)

Built to Last

The aftermarket for specific ICE parts and older generations of electronics and HMIs may prove attractive for suppliers considering this strategy, since the electrification of the industry is unlikely to significantly affect this part of the aftermarket in the mid-term. So, the potential exists to acquire current players in specific aftermarket segments that have yet to develop their own strategies due to the market’s uncertainties.

In addition, as OEMs increasingly shift their focus to their BEV operations, they are likely to turn to a few suppliers to provide the ICE systems and legacy electronics and HMIs needed, even as the market declines. This offers suppliers the opportunity to further consolidate specific system segments through the acquisition of tier-two and tier-three suppliers to these segments.

Finally, suppliers that see no future in specific aspects of their legacy operations will need to settle on a plan to shut the business down and completely reallocate resources. If certain legacy resources—both physical assets and talent pools—cannot be repurposed in support of new businesses, they should be divested entirely.

Conclusion

As the auto industry continues on its inevitable path to an electrified, connected, shared future, its tier-one suppliers are finding themselves in a live-or-die situation. The legacy business, while still robust, will start declining soon, and many suppliers simply aren’t prepared for what comes next, either strategically or operationally.

Under these conditions, suppliers must make some increasingly urgent strategic decisions. Do they make the changes necessary to thrive as vital links in the auto industry’s value chain? Or should they manage their current ICE and older electronics and HMI businesses to maximize value as long as the business is viable?

No matter which strategic choices suppliers decide to make, they must make them now. Competitive advantage goes to the first movers—for the rest, the choices will soon become severely limited.