In December 2021, European leaders returned home from the COP26 climate conference in Glasgow determined to honor pledges to back their climate commitments with concrete action. Since then, the European Union has issued a flurry of regulations applying environmental, social, and governance (ESG) standards to trade.

These measures are expected to significantly reduce CO2 emissions, protect greener European producers from unfair competition, and discourage bad trade practices. Their greatest economic impact, however, will likely be felt not in the EU but in emerging markets . Few companies and governments in developing nations are prepared for what is about to hit them. In the absence of a real sense of urgency, concrete actions, and multilateral cooperation, many are in jeopardy of being shut out of their key export markets.

Two of the most significant EU measures relate to climate. One is the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which will soon place the same price on carbon emissions associated with materials produced in developing nations—including steel, aluminum, and chemicals—that producers in the EU now pay. The other is the EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR), which bans the sale of commodities such as cocoa, coffee, palm oil, and timber harvested from recently cleared rainforest. This will affect important export industries in Latin America, Africa, and Southeast Asia.

Taken together, these and other climate- and values-based measures amount to one of the biggest changes to global trade since the creation of the World Trade Organization in 1995. They will eventually affect virtually every significant emerging-market export sector.

Emerging-market companies and governments must act now. The measures needed to remain competitive in Europe and in markets that adopt similar ESG rules can’t be implemented overnight. If they haven’t done so already, companies need to establish systems for documenting and reporting the greenhouse gas footprints and other data relating to their products and supply chains. And rather than merely react to new requirements as they arise, companies should adopt “ smart compliance ”—a pragmatic approach to fulfilling mandatory disclosure requirements. Companies also need a holistic strategy and game plan for decarbonizing and for improving their overall ESG performance.

The Growing Sustainability Imperative

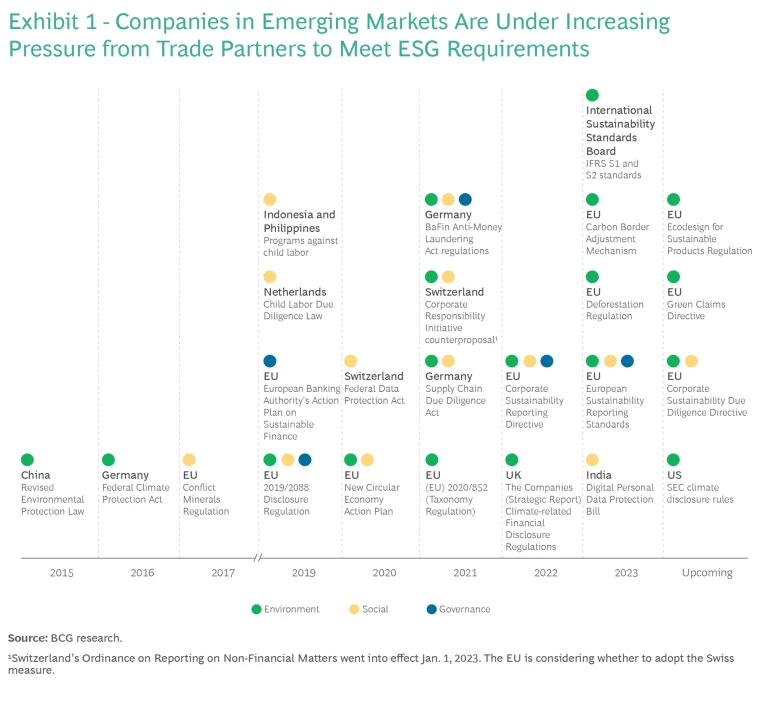

The movement to get companies to adhere to ESG standards has been gaining momentum in advanced economies for decades. Now, the sustainability movement is hitting emerging markets at full force. These nations, which by 2050 are expected to account for 62% of the global economy and 88% of the population, are crucial to mitigating climate change . Although they emit less CO2 per capita than advanced economies, they account for around 85% of the global total—a share that’s projected to grow. Emerging-market companies are under intensifying pressure, not just from the demands of their trade partners, but from consumers, investors, regulators, and employees at home and abroad to back their commitments with verifiable action. (See Exhibit 1.)

Besides the CBAM and EUDR, the European Sustainability Reporting Standards will require companies operating in the EU to disclose the sustainability of their value chains starting in the 2024 fiscal year. The EU has also enacted restrictions on importing certain minerals from conflict zones. In addition, the EU is considering a Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive that will require companies to address the effect of their practices on human rights and the environment, as well as “ecodesign” mandates intended to reduce the environmental impact of a product’s life cycle.

Establishing strict international sustainability standards is particularly challenging for companies in emerging markets. Their scores in influential international environmental sustainability rankings, for example, are about 20% lower than those of their G20 peers. This underperformance is understandable. Companies in advanced economies got off to a much earlier start on ESG, have faced heavier pressure from domestic regulators, and have access to vast government incentives to invest in green solutions. What’s more, industries that drive broad economic growth and development in many emerging markets, such as steel, chemicals, and transportation equipment, are inherently more carbon intensive.

Nevertheless, ESG is now a strategic imperative for emerging markets. Our research has found that large emerging-market companies in the vanguard of climate sustainability generated total shareholder returns for investors that were 105% higher than the MSCI Emerging Markets Index from 2017 through 2022. Companies meeting high ESG standards also enjoy greater access to markets, investment capital, and talent and have more opportunities to change the dynamics in their industries with climate- and values-driven business models. Creating value through ESG will become more challenging, of course, as regulatory pressure from the EU and other trade partners intensifies.

Finally, reliable ESG disclosure and reporting systems throughout companies’ supply chains will provide customers with the transparency they need to assess risks and fulfill their own sustainability commitments. Companies that fail to meet the new requirements, on the other hand, could well find themselves priced out—or completely excluded from—global value chains.

The Impact of CBAM on Emerging Markets

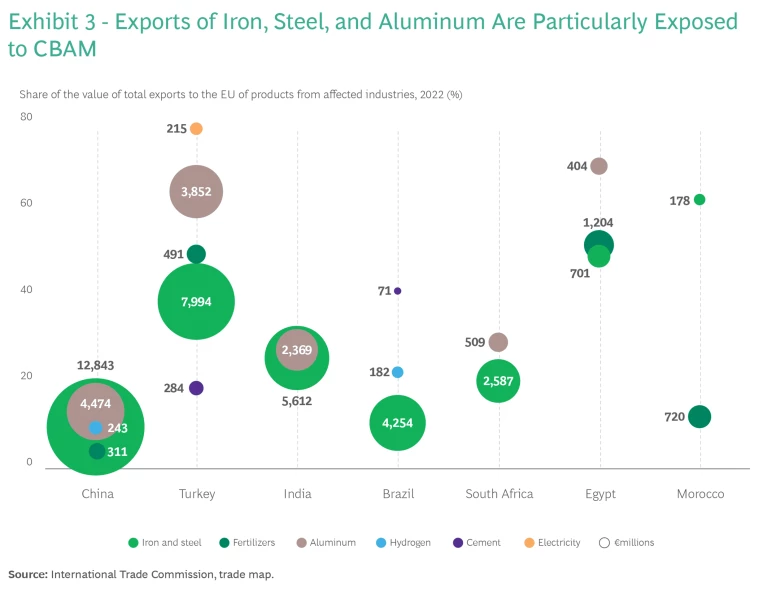

The EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, better known as the carbon border tax , involves a levy on the CO2 emissions associated with certain imported goods. Producers within the EU already pay around €85 per metric ton of CO2 equivalent for emissions, and that cost is projected to rise. The CBAM, which came into force on October 1, 2023, initially applies only to imports of electricity and certain carbon-intensive materials, including steel, aluminum, fertilizers, and cement. Importers must document and accurately report the entire carbon footprint of these goods or risk penalties. Starting in 2026, they will also have to pay the levy, which will phase in over eight years.

In its initial stage, CBAM applies to only around 5% of EU imports. That share will likely increase considerably as the program’s scope expands. By 2030, the carbon tax could cover imports such as chemicals, refined-oil products, and pulp and paper. By 2040, high-emission finished and semifinished goods such as cars could also be included.

The CBAM will fundamentally alter the cost competitiveness of many products brought into the EU. Traditionally, companies have viewed eco-friendly goods in terms of a “green premium”—the extra cost of buying a low-carbon product compared with a high-carbon one. CBAM, in effect, imposes a significant “brown penalty” on carbon-intensive goods. When the first big green steel plants begin production around 2025, for example, their output will cost significantly more than “grey” steel made with traditional methods. By the late 2030s, however, production costs are expected to be at parity owing to the combination of higher carbon costs and lower prices for green hydrogen fuel.

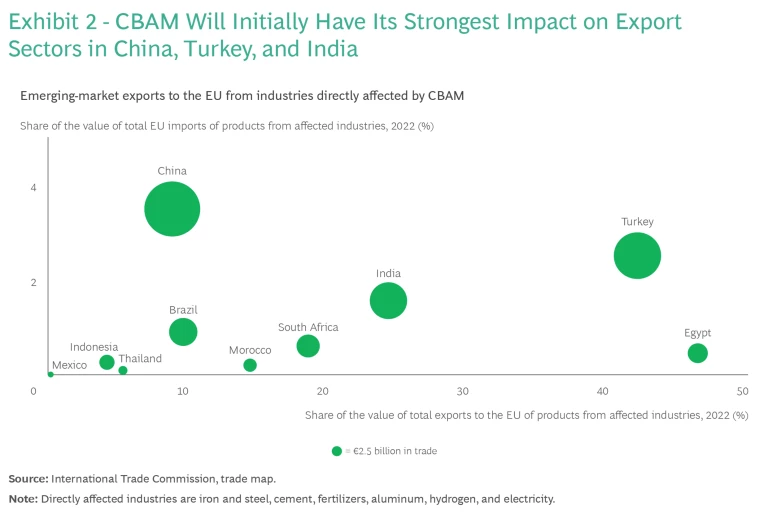

Even with its initial limited scope, the CBAM’s impact on certain emerging-market industries and economies could be severe. The EU relies on most major emerging markets for only a tiny portion of its total imports. But the carbon tax could apply to nearly 10% of the value of exports to the EU of both China and Brazil, to more than 25% of the value of India’s exports to the EU, and to more than 40% of the value of exports to the EU of Egypt and Turkey, both major producers of iron, steel, and fertilizers. (See Exhibits 2 and 3.) More than half of Mozambique’s aluminum exports currently go to the EU; unless it can decarbonize this sector, analysts estimate the country stands to lose as much as 1.6% of its GDP as a result of the CBAM.

The Impact of EUDR on Emerging Markets

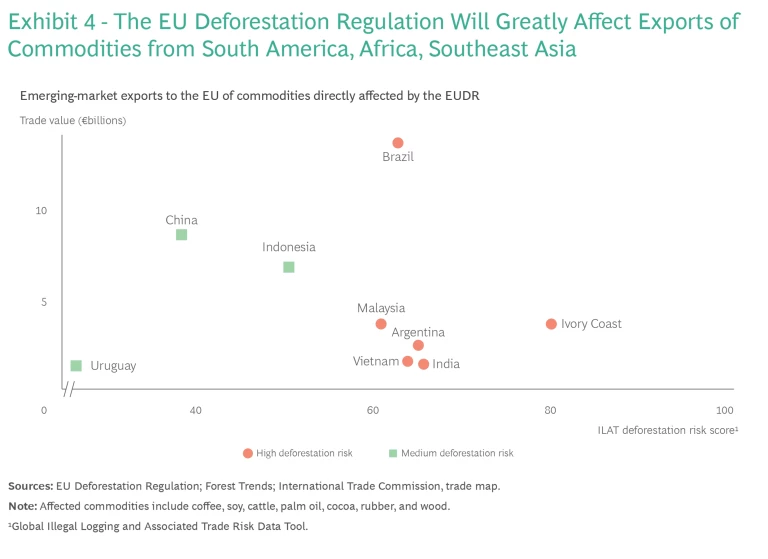

The EU Deforestation Regulation will have its greatest impact on a different set of industries and countries. EUDR prohibits the sale in the EU of products produced on land that has been deforested since 2020. When it goes into effect in 2025, the measure will apply to cattle, cocoa, coffee, palm oil, rubber, soy, and wood products.

EU importers will have to verify that goods have not come from deforested land. Imports from nations with the highest deforestation risk will draw the closest scrutiny. The European Commission classifies nations as “high risk” if 9% or more of their goods are harvested from recently deforested land.

The reporting burden for producers in high-risk countries will be significant. To ensure that their products keep flowing to the EU, they will need to provide importers with risk-assessed data and evidence that deforestation has not occurred. Verification can include ground audits and satellite imaging data. The EU will also establish an observatory—using its Copernicus earth observation satellites—to verify producer information.

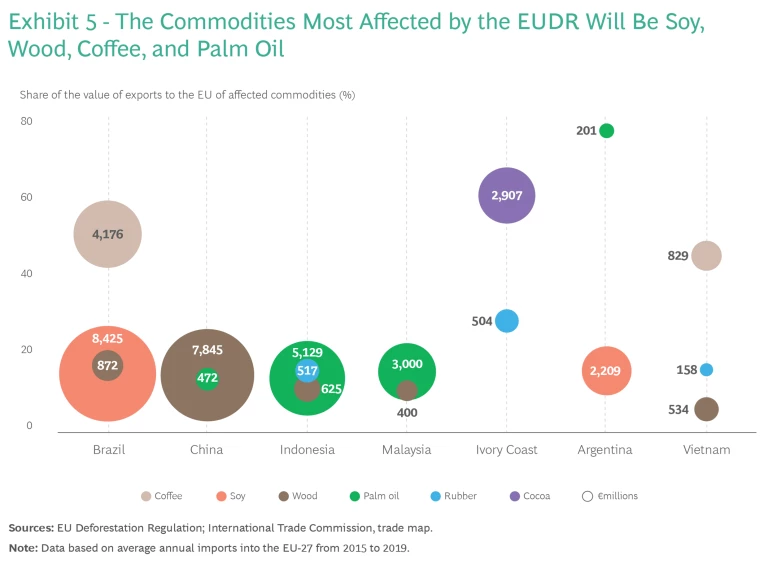

As with CBAM, the EUDR will initially have minimal economic impact on the EU itself. In its first phase, the deforestation regulation will directly apply to only around 2% of the trade bloc’s imports. But for certain products, the consequences will be great. An estimated €14 billion of imported Brazilian coffee and soy, much of which is grown on former rainforest, and €8 billion in Chinese wood products are at risk. (See Exhibit 4.) Around 20% of Indonesian and Malaysian palm oil and 60% of Ivory Coast coffee will be affected. (See Exhibit 5.)

A Roadmap for ESG Readiness

Companies in emerging markets still have time to take the actions needed to remain competitive in the EU, as well as in other markets that are tying access to ESG. But they must act now. Attaining globally competitive sustainability will require a multiphase journey.

The journey begins with a comprehensive ESG readiness assessment that evaluates how well the organization is prepared to achieve high sustainability standards across various dimensions:

- Map the relevance of ESG regulations. Analyze all new rules and requirements issued by the EU and other key trade partners and assess their impact on your products and supply chains.

- Identify measurement, reporting, and capability gaps. Evaluate your company’s capabilities to deliver low-carbon products and comply with values-based criteria. For example, determine whether you have the systems in place to document and report the carbon footprint of your product portfolio. Assess whether your company’s operating model needs revision.

- Develop a holistic sustainability transformation roadmap. Identify the actions you must take to improve ESG performance in order to remain cost competitive in key markets and avoid penalties.

After completing this assessment, develop a roadmap for not only complying with specific trade-related regulations but also for attaining the high level of ESG performance that can give your company a global competitive advantage. The roadmap should address the following parameters:

- Strategy. Firmly embed sustainability principles into your company’s strategy. Set high ESG ambitions and outline a corporate transformation program to attain them. Align your ESG strategy with your corporate strategy.

- Governance and Organization. The board of directors should establish a mandate for sustainability. Adopt an ESG policy framework. Designate and empower global functional leaders to deliver on this mandate.

- Enablers. Launch initiatives to instill ESG commitments within the organization’s culture and people. Build ESG data and analytics capabilities enabled by advanced digital technologies.

- Products and Services. Work with suppliers and technology developers to ensure that existing products and services comply with coming ESG standards and design sustainability into new ones.

- Regulation-Specific Capabilities. Develop the capabilities required to comply with the regulations of your trade partners as they are phased in. In the case of CBAM, for example, this would include systems for disclosing detailed information on your products’ carbon content; measuring the emissions associated with the production, distribution, and consumption of specific products; and maintaining and documenting accurate records of carbon taxes paid for raw materials.

Global Coordination an Imperative for Trade

There is a very strong correlation between global trade and global GDP. Yet trade is likely to become an increasingly powerful tool for promoting sustainability. Emerging markets obviously can’t be expected to solve such problems on their own. It won’t be enough for advanced economies to unilaterally impose mandates on their trade partners with little coordination. The global community must help emerging markets make the transition to sustainable industries and economic growth. International institutions and advanced economies should provide technical, financial, and managerial assistance to address situations such as the one in Mozambique.

A recent report from the World Economic Forum, in collaboration with BCG, on the future of climate and trade recommended actions governments should undertake collaboratively to help nations both mitigate emissions and make their industries carbon competitive. They should align their carbon accounting and reporting standards, agree on principles for deploying green subsidies, make multination “climate clubs” as inclusive as possible, and use international institutions coherently. Advanced economies should also develop green development assistance programs to help less developed nations make the transition.

The proliferation of new ESG-linked regulations from trade partners and other stakeholders presents daunting challenges for emerging-market companies. Failure to respond will amount to a massive loss of income for some of the world’s most vulnerable populations. Achieving compliance is entirely possible if companies and governments begin the process now. Being at the forefront of sustainability can create competitive advantages that will open huge potential opportunities over the long run.