Over the last decade public sector agencies have expanded their risk management practices, yet they have not kept pace with the global risk landscape, which now entails a wider range of more complex risks that hit harder, come faster, are interconnected, and bring more profound disruptions. Public sector agencies need to expand and enhance their approach to risk—applying best practices from the private sector to become far more anticipatory, proactive, and risk-intelligent.

We interviewed former and current government employees intimately involved in risk management at large US agencies with national or global missions, including both defense and non-defense. A common theme emerged: while most are doing admirable work, they often apply a defensive, reactive risk management that rarely considers broader strategic risks that can impact their objectives and create significant disruptions. They also overwhelmingly view risk as a negative, thereby missing the opportunity side of the coin where they may take calculated risks to advance their strategic objectives. To be clear, we understand that public sector risk management professionals face an uphill battle of a different set of parameters and constraints than private sector risk entities and are often limited by the highly bureaucratic and fragmented nature of their organizations.

Government agencies overwhelmingly view risk as a negative, thereby missing the opportunity side of the coin.

Our analysis derived lessons from the private sector that could help public sector agencies shift away from a predominantly reactive, tactical compliance-oriented approach, to one that is more anticipatory and proactive in confronting and intelligently managing strategic risks. We identified four steps (see below) that public sector agencies will be able to take, applying a risk lens to everything they do and gaining a competitive advantage while still protecting value. In this way they will be better able to meet the needs of their citizen stakeholders.

Limitations to Current Risk Management Practices in the Public Sector

A central challenge is that many public sector agencies do not have strong risk management processes in place to foresee, sense, and deal with strategic risks such as geopolitical tension, climate change, supply chain disruptions, cybersecurity , and others before they materialize and their impacts are felt. In 2021, for example, the inspector general (IG) of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) found that the Agency, despite possessing risk management procedures across its programs and offices, had never conducted an agency-level risk assessment. The IG concluded that this left the EPA exposed to potentially significant risks, stating that the centralized risk entity within the EPA, “cannot provide the direction necessary for its own office, let alone management and staff across the Agency, to perform enterprise risk-management responsibilities.”

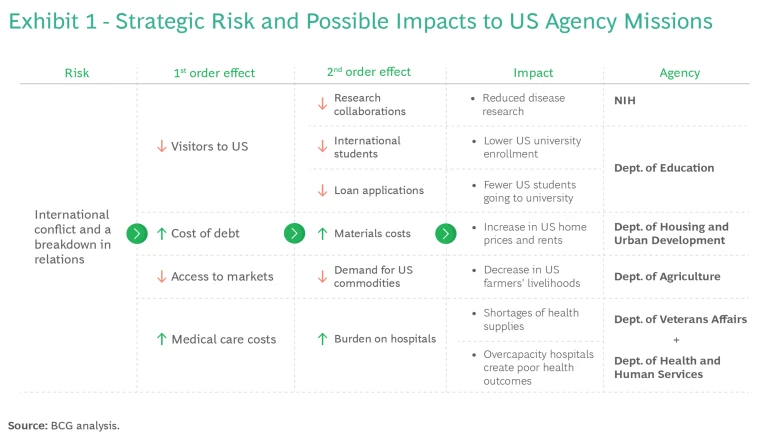

The EPA is perhaps an extreme example, but it’s not alone. The challenge is growing. As Exhibit 1 shows, public-sector entities are exposed to a range of increased geopolitical risk. Many public sector agencies apply a largely defensive, siloed, inward-looking, compliance-based approach to risk management, ignoring the broader strategic risks that could prevent them from achieving their stated strategic objectives. This is in direct contrast with the risk management mindset and approach of leading private sector organizations. BCG research across ten large multinational corporations found that companies are increasingly preparing for strategic disruptions like geopolitical risks through proactive risk management to enable strategic resilience—and even create new advantages by embracing the appropriate level of risk.

BCG research across ten large multinational corporations found that companies are increasingly preparing for strategic disruptions.

Most public sector agencies do have a baseline of risk management processes, and many conduct periodic risk reviews. Yet they face a range of obstacles in advancing their risk-management processes. Broadly, our interviews point to five such obstacles.

Agencies do not sufficiently link risk to strategy

Typically, strategic planning and risk management follow a sequential pattern: an agency develops a multi-year plan with specific strategic objectives, the offices then identify risks to the objectives under their purview, and the offices then manage those risks over time, with formalized annual reviews. This kind of linear approach helps ensure the risks identified are truly “strategic” in nature, but the information only flows in one direction. For example, one former chief risk officer (CRO) in government told us that neither she nor her risk team were privy to the strategic planning process or resultant comprehensive strategy materials; they simply received the final strategic plan after it was published.

The lack of a feedback loop prohibits agencies from revising the strategic plan to incorporate preparedness and management measures for the identified risks. It does not provide a risk lens to inform the development of the strategic objectives in the first place. Nor does it usually take into account risks from the strategy's intended and unintended consequences.

Agencies lack formal, centralized tools to sense, anticipate, monitor, and manage risks

At many public sector agencies, the responsibility for monitoring and managing risk is often delegated to lower-level offices, without centralized guidance or oversight, or direct linkage to the agency’s stated strategic objectives. Yet without centralized processes, these teams lack the necessary tools to develop the skills for sensing and identifying risks before they happen. Building such anticipatory strategic foresight would increase the lead times agencies have to prepare for, and even shape, impending risks.

One interviewee suggested as much: in response to a question about what could be improved about the risk management process at public sector agencies, the interviewee told us, “We need to do more thinking about what risks look like before they actually materialize. I don’t think any agency is doing enough of that.”

Another interviewed agency mentioned an overseas loan program that emphasized risks around project completion and loan repayment. These risks—which could clearly arise during interstate conflict—were largely monitored informally by the relevant program leaders, instead of through a more systematic process.

Subscribe to our Public Sector E-Alert.

Risks are identified at the lowest levels of the agency

Many interviewees said that their agencies often delegate risk identification to the lowest levels of their organization. Individual offices, bureaus, or programs identify the risks they see, which are then consolidated by a centralized risk entity. Although this bottom-up approach has the benefit of spreading the responsibility (and culture) of risk management throughout the organization, it has shortcomings. For example, lower-level offices can effectively identify programmatic or tactical risks, but these are generally considered independently and in isolation, without addressing the potential interplay among multiple risks that may impact more than one department or directorate. Moreover, this approach is less effective at identifying higher-level strategic risks

We spoke with employees at one office that administered a loan and grant program, where risk management process focused largely on internal controls to ensure the loans it disbursed were safe. This office—and the rest of the agency—found itself caught off-guard when geopolitical tensions resulted in a significant decline in US visas being issued. Because the department had not identified this potential risk, its potential effects, or early warning indicators of its manifestation, constituents and stakeholders of the agency were unprepared, experienced significant bureaucratic pain, and had to scramble to respond.

Agencies prioritize risks using subjective criteria

After developing a long list of potential risks via the bottom-up approach, interviewees told us their agencies would cull the list based on the traditional approach to risks as a factor of their probability and impact. Yet without objective criteria to quantify “high impact” and “high probability,” the designations can be highly subjective. The process can also become an overly academic discussion about probability, instead of focusing on impact and preparedness. Moreover, some offices may use a different rubric than others, thus making comparisons of probability or impact across an aggregated set of risks difficult and often impractical.

We found that organizations often fixate on probability estimates, which are increasingly difficult to quantify—especially for low-probability events and previously unheard-of “black swan” events—allowing that to outweigh the impact estimates, leaving the organizations more vulnerable. In one example from our interviews, an agency had correctly anticipated the large negative impact of a geopolitical scenario in which the cross-border flow of goods was slowed. But because it deemed this to be a low-probability event, it never took the necessary steps to prepare for it.

Overreliance on imperfect and/or subjective likelihood scores leaves organizations underprepared for impactful events. Instead, organizations should use an exercise in which they assume all events have a 1.0 probability and focus on their preparedness for these disruptions to occur, by answering questions such as: “Are we as prepared as we think we are?” and “Are we as prepared as we need to be?”

Are we as prepared as we think we are? Are we as prepared as we need to be?

Agencies focus primarily on compliance

Another common theme of our interviews was that agencies pay the most attention to risks that could erode their political capital. For example, many US agencies have explicit requirements from the Office of Personnel Management and other governmental bodies to emphasize compliance risks. As a result, their processes focus on internal sources of noncompliance, placing them in jeopardy of ignoring broader external conditions. This focus is shifting a bit with updated guidance coming from the Department of Justice that encourages expanding approaches and changing how organizations think about compliance from simply being bureaucratic to actually adding value, but the behavioral change will take time.

Compliance-oriented agencies adopt a mindset of “zero defects,” which may lead to missed opportunities an agency could pursue by setting an acceptable level of risk appetite. This reflects the limitations of viewing risk as only a negative that presents threats or challenges, wholly ignoring the other side of the risk coin: opportunity. For example, a loan or grant program office may seek to mitigate risks that could improperly award funds to unauthorized recipients. While important, this focus can miss opportunities for greater impact from each award, such as introducing new types of grants.

Four Low-Cost Measures for Public Sector Agencies to Improve Their Strategic Resilience

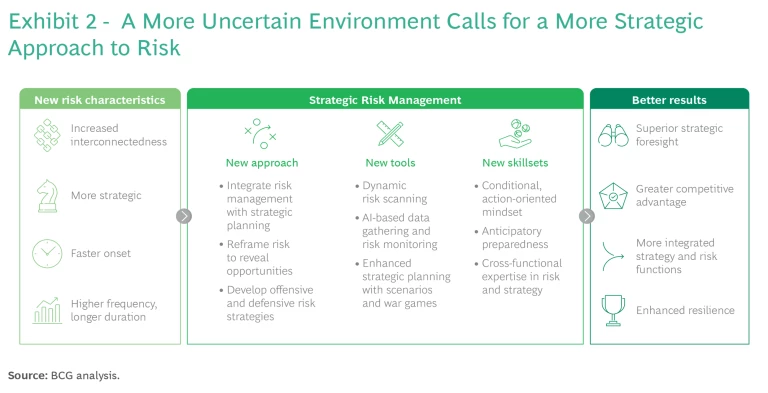

In today's increasing uncertainty and complexity, public sector agencies need to immediately enhance their risk management capabilities and embrace new ways of thinking about and perceiving risk. Many private sector organizations have already implemented proactive anticipatory strategic risk management approaches that public sector agencies can adopt to increase their risk intelligence. (See Exhibit 2.)

We have identified four steps for this with the biggest impact and the lowest cost. In fact, most do not require any investment to implement.

Stress-test strategies and assumptions using scenarios, war gaming, and other tools

In the private sector, a best practice for identifying risks and prioritizing management decisions involves stress-testing strategic objectives and planning assumptions against multiple actors and motivations using “stretched but plausible” scenarios. Under this approach, an agency would take the following steps:

- Develop several whole-world scenarios that explore more geopolitical and other potential strategic risks.

- War game each scenario to identify potential outcomes and actor moves and motivations.

- Assess resulting impacts on and from achieving the agency’s strategic objectives using a business risk framework, considering such dimensions as supply risk, demand risk, people risk, and reputation risk.

- Quantify the aggregate impact using key performance indicators (KPIs).

- Develop a list of leading key risk indicators (KRIs) to provide advanced warning.

- Identify and prioritize risk management actions based on impact and preparedness.

War gaming: stress-test strategic objectives and planning assumptions against multiple actors and motivations using “stretched but plausible” scenarios.

In contrast to the distributed or siloed approach to risk identification that agencies typically follow today, which results in a list of individual risks, these scenarios enable agencies to capture the interplay of multiple dynamic risks. This kind of scenario planning process is typically accomplished through an annual two- to three-day workshop led by an existing risk or executive committee.

The workshop identifies and prioritizes risks that can have potentially high impact on one or more of the organization’s strategic objectives. It aims to integrate this thinking into the larger strategic planning processes and ensure the right risk management resources are in place.

Notably, it doesn’t require estimating the likelihood of a specific risk. Instead, it focuses the thinking on impact and preparedness. Participants explore scenario outcomes across different planning dimensions and drivers of risk for the organization, and then synthesize them to specific KPIs and KRIs. (See the sidebar “An Industrial Goods Company Uses Scenario-Planning to Assess Geopolitical Risks.”)

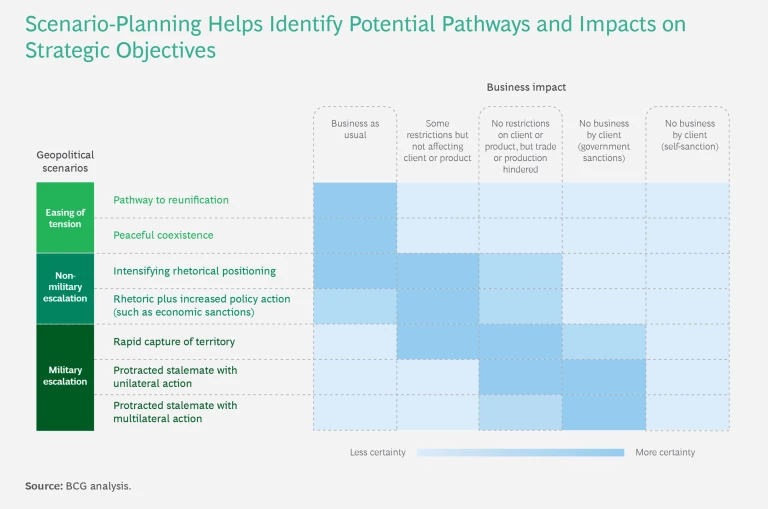

An Industrial Goods Company Uses Scenario Planning to Assess Geopolitical Risks

An Industrial Goods Company Uses Scenario Planning to Assess Geopolitical Risks

For each scenario, the risk team estimated the total impact on the company’s business, including sales and other KPIs. From that baseline, management developed a set of “no regret” actions that would help it regardless of whether a specific scenario played out. It established a more dynamic relationship with key organizations throughout its ecosystem and developed a signaling system that would give the company an early indication of specific scenarios materializing (based on KRIs). It also created playbooks with a range of actions relative to the scenarios so that leaders had the tools they needed to intelligently anticipate and proactively respond to these risks—actions to include shaping and accelerating advantageous actions in addition to mitigating and decelerating disadvantageous ones. Leaders could thus focus on executing those measures rather than determining them.

Transform the risk function into a strategic risk center of excellence

Although most agencies have a dedicated entity or team responsible for consolidating risk management evaluations, the mandate for these entities is often limited to rote processes. They issue instructions to offices for identifying risks (for example, how to fill out the forms) and compile risk lists from the offices. Occasionally, they may ask for clarification on a risk impact or inquire whether a certain risk was considered.

The most strategic-risk-intelligent organizations, however, enable these existing risk centers to assume a more anticipatory, strategic, and active role. CROs sit at the same level as chief strategy officers (CSOs), and their teams serve as thought partners to offices, remain current on the latest developments to provide offices with new risks for consideration, and disseminate ideas and best practices. The CROs also serve as facilitators of discussion that brings together the risk representatives from across all the offices, essentially bringing a risk lens to strategy development and a strategy lens to risk management. (See Exhibit 3.)

However, success requires more than just the CRO. It means a more holistic approach to embed risk thinking into departments and divisions and make people, processes, and technology more interconnected in how they manage strategic risk. Elevating an agency’s existing centralized risk function and incorporating first-line accountabilities and incentives transforms the risk assessment process: it moves from a passive check-the-box exercise into a deliberative, effective collaboration that anticipates, identifies, assesses, and proactively manages more of the strategic risks that truly matter. It realigns the culture away from a “zero defects” mindset to one of entrepreneurship, where taking calculated risk is encouraged to identify investments or actions that can deliver larger impact for the organization. In other words, it shifts the organization from being risk-compliant to risk-intelligent. (See the sidebar “An Insurance Company Transforms Its Risk Office.”)

Realign the risk culture away from a compliance-oriented “zero defects” mindset to one of opportunity and entrepreneurship, taking calculated risk to deliver larger impact for the organization.

An Insurance Company Transforms Its Risk Office

An Insurance Company Transforms Its Risk Office

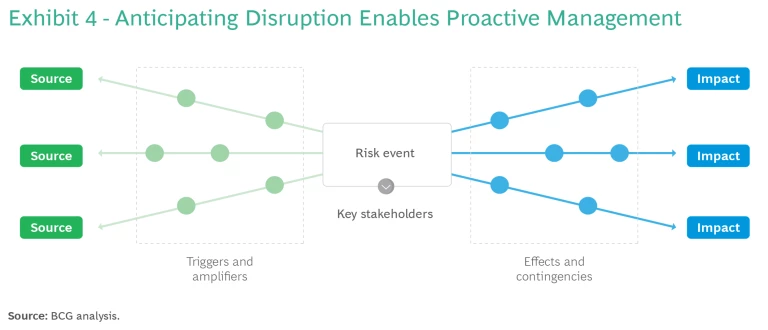

Adopt sensing and signaling systems to give early indications of imminent risks

Outside of the agencies directly responsible for health or national security risks, few put much effort toward monitoring leading risk indicators, triggers, or amplifiers. Leading organizations, however, look “left of boom”—i.e., to causal conditions or related indicators. These are monitored to give early warning of an impending risk or risk scenario. In contrast, looking “right of boom” only sees the effects and crisis management strategies after a disruption has occurred.

Public sector agencies can use a similar approach by establishing systems that can sense and anticipate early warning indicators and even weak signals, analyze them, and disseminate them to the right entities. (See Exhibit 4.) Doing so enables a signal advantage, buying additional time prior to a risk materializing—and creating a decisive move advantage to shape risk events in advance, rather than waiting to passively experience them. Through this approach, agencies can seize the initiative instead of ceding the initiative.

Sensing systems can include automated feeds and dedicated dashboards, but a useful low-tech start is also available: publish weekly or monthly risk updates across the organization to alert offices to materializing changes in the strategic risk environment. A key to the success of this system is ensuring that early warning risk signals are reviewed and discussed frequently (weekly, monthly, or at least quarterly) rather than only in the common annual cycle in place at many agencies. These frequent alerts should also identify what steps an agency could take today to affect those risks. (See the sidebar “A Global Energy Company Builds a Risk Dashboard to Anticipate Emerging Risks.”)

A Global Energy Company Builds a Risk Dashboard to Anticipate Emerging Risks

A Global Energy Company Builds a Risk Dashboard to Anticipate Emerging Risks

Feed advance signals and risk evaluations into strategic planning to identify opportunities

Most agencies devise and publish a strategy, assess risks to that strategy, and craft contingency response plans. The linear, sequential nature of this process means that risk assessment and contingency planning are often after-the-fact considerations, if at all. Instead, that information should be fed back into the overall strategy design. In that way, agencies can consider risks—including upside opportunities—before setting (or recommitting to) a long-term strategy. Such an approach creates/enhances strategic resilience by embedding anticipatory risk intelligence, informed responsiveness, and agility into the strategy itself. In this way, it shapes the strategic vision at the beginning of a development process, where value creation is emphasized, rather than pigeonholing risk management near the end of the process and focusing almost exclusively on value protection. (See the sidebar “A Cloud-Services Provider Integrates Risk into Its Strategy Design Process.”)

A Cloud-Services Provider Integrates Risk into Its Strategy Design Process

A Cloud-Services Provider Integrates Risk into Its Strategy Design Process

In an increasingly uncertain world, public agency risk management must become more proactive, anticipatory, and risk-intelligent.

In an increasingly uncertain world, public agencies must adapt their reactive, compliance-focused risk management programs and become more proactive, anticipatory, and risk-intelligent. Best-in-class private sector organizations have developed measures that improve the effectiveness of their risk management practices, better preparing for the broad range of strategic risks. It is imperative for public sector agencies to adopt these practices, building on their existing structures and resources to improve their preparedness to seize the initiative and make the strategic environment react to them, instead of ceding the initiative to the disruption, and merely reacting when it manifests.