This article was originally published in October 2023 and updated in April 2024.

Business is finally recognizing the importance of dealing with the hidden risks in global supply chains. As highlighted by the recent pandemic and the ongoing conflict in Europe, as well as natural disasters around the world, the vulnerability of global supply chains has only risen over time.

Part of the problem is that business has limited visibility into or control over supply chains, especially the links located in emerging markets. Due to this lack of transparency, many corporations have little understanding of the adverse impact of their supply chains on the environment; employees, especially those indirectly employed; and on society at large.

Meanwhile, shareholders and stakeholders have been demanding greater accountability from companies. Companies are under enormous pressure to take responsibility for the environmental, social, and governance (ESG) impacts of their operations and to ensure that they’re doing business in an ethical, sustainable, and fair fashion. Approaches might have to vary by country, but society now expects the same standards to be enforced throughout a company’s global supply chain. As one of the coauthors of this article (Weise) argued in a recent book, companies can become sustainable only by teaming up with suppliers to adhere to ESG

Until now, the case to resolve ESG issues in supply chains has rested mainly on reputational risks. When corporate images take a beating, CEOs must deal with falling revenues, lower profits, hindered access to capital, shrinking valuations, and declining attractiveness as employers. The last is inevitable; according to BCG data, 40% of Millennials use ESG criteria when choosing the companies they want to work for.

However, the business case for managing ESG issues now goes far beyond reputation—it is increasingly becoming a source of value creation. When companies pursue ESG-related goals, they accrue advantages ranging from the creation of alternative sourcing routes and the development of new technologies and offerings to better employee, shareholder, and consumer relations. Companies that manage ESG issues enjoy higher profit margins of between one and three percentage points, according to recent BCG studies, and stock market premiums of over 10%. That’s why managing ESG issues in supply chains has become a priority in more than one sense today.

The New Global Push for ESG

Many companies take their ESG responsibilities for granted, particularly those relating to human rights. But now several countries, especially in Europe and North America, are planning to enact new laws or rigorously implement existing regulations to safeguard people working at every stage of a supply chain. These laws will make the due diligence process mandatory, impose more obligations and stricter sanctions on businesses, and create new enforcement bodies.

The most comprehensive of these initiatives will be the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD), which was ratified by the European Commission in 2022 and adopted by the EU Parliament in April 2024. It requires both EU and non-EU companies operating in the EU to take responsibility for the environmental and social impacts of their value chains, including those of suppliers and their sub-suppliers and business partners, imposing fines of as much as 5% of global turnover if abuses are identified. After the CSDDD is formally adopted, EU member states will have two years to embed it into their national laws.

The EU initiative builds on recent legislation such as the UK Modern Slavery Act of March 2015, the Australia Modern Slavery Act of January 2019, and Germany’s Supply Chain Due Diligence Act, which came into effect in January 2023. The last-named requires all German companies with over 3,000 employees to establish, implement, and update due diligence procedures. They will have to monitor human rights violations in their own operations as well as those of direct suppliers both at home and abroad. If a company doing business in Germany becomes aware of a possible violation of human rights by an indirect supplier, it must perform a risk analysis and respond accordingly.

Interplay among human rights concerns and politics across international and domestic fronts have led to an increased number of sanctions. In November 2022, the United States banned sugar imports from the Dominican Republic’s Central Romana Sugar. Earlier, it used the 2021 Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act to stop imports of solar panels and components from China. That resulted in over 3,000 shipments being detained at US borders last year—twice as many as in 2021.

Mitigating ESG Risks

It has been tough for companies, especially for large corporations based in the developed world, to tackle ESG issues in supply chains for several reasons. For one thing, supply chains have become more complex in terms of structures as well as business models. They span countries with different legal, regulatory, and human rights practices, with many suppliers contributing to each product and complex interrelationships between supplier tiers.

As supply chains become deeper, visibility becomes poorer and the likelihood of violations rises.

For another, as supply chains become deeper, visibility becomes poorer and the likelihood of violations rises, with tier n suppliers likely to overlook more abuses than tier one or tier two suppliers. In fact, ESG issues usually involve lower-tier suppliers and subcontractors, whose exploitation of employees can go unnoticed, especially since the workers most affected—often women, migrants, and children—have few ways of fighting back or drawing attention to their plight.

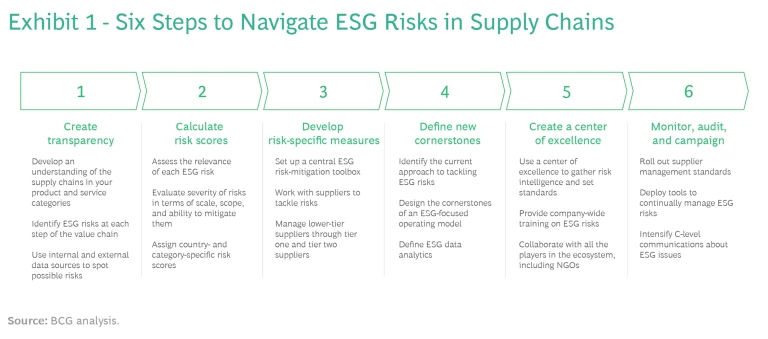

Our recent experience and studies suggest that companies can take six steps to tackle the challenge. Some of them relate to assessing risks, while others embed ESG risk management deep in the organization (see Exhibit 1).

Create Transparency. The starting point must be for the organization to develop an in-depth understanding of all its supply chains, which can extend across the globe and have many layers, as well as the various steps in the sourcing and manufacturing processes. After tracing each supply chain from end to end, the company should assess trade flows as well as the countries and suppliers involved. It will then be able to identify the potential ESG risks that form the basis on which it can calculate risk scores.

There are different ways of gauging these risks, depending on the company’s ambition levels, resources, and data requirements. One is to trace the supply flows of both raw materials and finished goods by using company data and publicly available information from, for instance, global databases. Repeating the process as far down each supply chain as possible allows a company to develop a comprehensive snapshot of all its sub-suppliers by country and by product.

For instance, a global construction materials firm recently traced one of its key supply chains, which extends from bauxite mines (raw material) to aluminum window-frame (finished product) retailers. It found that the bauxite was mined mainly in Guinea, Australia, Vietnam, and Brazil; alumina and pure aluminum were then extracted using electrolysis; the aluminium was converted into semi-fabricated products; and the company distributed the end products it made to transportation and construction companies worldwide. Based on the analysis, the company was able to identify all the countries where suppliers performed these steps as well as the possible human rights risks; it then assigned risk scores to them.

An alternative approach is to track global trade flows using country-specific import and export data. Executives can trace the raw materials, components, and services they purchase to their source countries, which will turn up critical insights.

Calculate Risk Scores. Once companies understand their supply chains and material flows, they will be able to assess the ESG risks they face in their own facilities—such as factories, distribution centers, and warehouses—as well as the often larger risks present in the many levels of their supply chains. Each score they assign will be specific to the category and country in which it could occur, the nature of the risk, and the supply chain tier. These scores are essential to help companies better manage the likelihood of violations.

To calculate the magnitude of ESG risks, companies can assign scores that represent the probability of adverse events and their severity, focusing principally on the latter. They can assess the severity by taking into account an issue’s scale, scope, and possible remedies (See Exhibit 2.) These aspects are enshrined in globally accepted approaches such as the OECD’s Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.

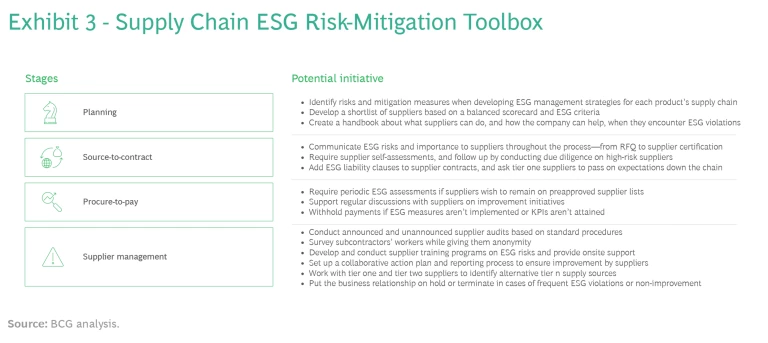

Develop Risk-Specific Measures. It’s important to interact closely with suppliers on risk identification and incident management. Developing a standardized, company-specific toolbox will help companies identify risks and mitigation measures along the procurement process. (See Exhibit 3.)

Selecting the right tool will be critical. During the planning stage, the procurement function, in tandem with cross-functional teams, should identify the possible risks that each supplier poses along with the appropriate mitigation initiatives. Each business unit must take responsibility for reporting instances of possible supplier misconduct to headquarters. It must also protect the organization from possible retaliation by identifying alternative supply sources in advance.

From the sourcing to the contracting stages, which come next, companies can communicate the risk factors and their importance to vendors through the RFP process. Some leaders use ESG scorecards as part of the selection criteria to evaluate suppliers’ offers. Another way of holding suppliers accountable is to add liability clauses to contracts.

A company’s procurement function can usually manage the lower supplier tiers on an ongoing basis with the aid of tier one and tier two suppliers, asking the former to pass on their expectations to sub-suppliers. It will ensure mitigation by drawing up contracts that give the company the right to withhold payments if countermeasures aren’t implemented in time.

Companies need to interact closely with suppliers on risk identification and incident management.

Based on the severity of the violation and the supplier’s willingness to amend ESG breaches, it’s critical for companies to help their suppliers do better over time. Many corporations demand self-assessments from vendors that wish to remain on preapproved supplier lists; and they support them by helping them to identify improvement initiatives and rewarding suppliers that develop best practices in managing ESG risks with additional or concessional financing.

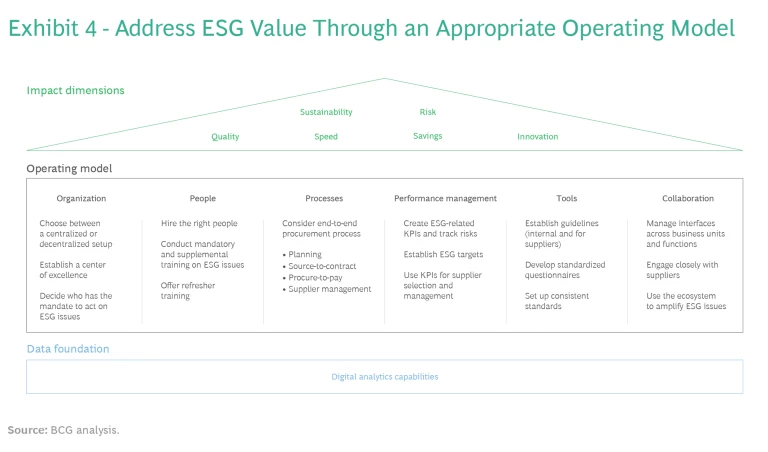

Define New Cornerstones. Before transitioning to an operating model that places ESG risk management at its core, an organization must analyze its current approach. This starts by focusing on existing policies, the functions involved, and the current roles and responsibilities.

Then, the company should map out the cornerstones of an ESG-focused operating model. It must identify the best practices for the key elements—namely, organization structure, people, processes, performance management, tools, and collaboration—as well as the digital foundation (e.g., to monitor ESG compliance and identify potential risks). (See Exhibit 4).

One global energy player recently compared its default operating model as well as its recent performance on ESG issues against that of the peers in its industry. Based on the results, it identified the areas where it simply wanted to comply with regulations; where it wanted to compete with peers; and where it could take the lead in setting ESG standards and managing risks. It found, for instance, that it didn’t focus on ESG issues in business processes, which limited the indicators it tracked. It also didn’t provide mandatory training for all its employees, so it lagged the leaders.

Organizations can mitigate risks by taking a combination of measures such as training, engaging with suppliers, and collaborating with other companies in their ecosystems. They must ensure that all the relevant functions—especially sustainability, procurement, operations, and legal—are involved in the process and establish group-level guidelines for them to follow.

Create a Center of Excellence. Once a company has refined its operating model to account for ESG issues and defined the roles to operate it, the responsibilities for execution should be transferred to the organization’s businesses and functions. Some leaders establish a center of excellence as an organizational node.

This center enables a clear view of risk management and mitigation across the company. It ensures consistency in the development of ESG guidelines, sharing of best practices, and performance tracking. A center also catalyzes internal collaboration by setting guidelines and requirements for each unit and providing toolboxes for supplier risk assessment, supplier engagement, and risk mitigation. For example, a European supplier of aerospace components recently set up a center of excellence that tackles supply-chain-related ESG issues on two fronts. One, it tracks ESG risks, trains employees, and manages mitigation in supply chains. Two, it also defines supplier standards and tracks business units’ performance on improving them.

A center of excellence catalyzes internal collaboration by setting guidelines and providing toolboxes for supplier risk assessment, supplier engagement, and risk mitigation.

A center of excellence can organize mandatory training on ESG issues for all employees and provide specialized training to the teams that deal with high-risk suppliers. Creating a central knowledge repository will ensure that the company doesn’t lose data and knowledge over time. Such centers can also take the lead in collaborating with NGOs and external organizations. Doing so will help the organization gain a broader perspective on supply chain risks as well as share its own experiences widely. In addition, visionary CEOs will start and support sectoral initiatives to raise awareness about the key ESG issues in their supply chains.

Monitor, Audit, and Campaign. To manage risks over time, most ESG leaders have drawn up a specific set of parameters and deployed digital systems to monitor them constantly. In addition, they conduct periodic audits and reviews to improve suppliers’ performances, especially those of smaller vendors.

After categorizing suppliers by the severity of the risks they pose, most organizations conduct in-person audits of the most vulnerable vendors. They also use self-assessments and conduct desktop audits to gauge the effectiveness of the measures they’ve put in place. In addition, companies routinely conduct interviews with suppliers, survey their workers, and analyze any adverse mentions of these vendors, especially on the internet. Setting up hotlines over which workers can report violations anonymously often helps identify potential trouble spots.

Creating web portals where suppliers can periodically upload data and compare themselves with similar organizations can also prompt the suppliers’ peers to do better on ESG parameters. Many digital tools have been developed to help with ESG issues; the resilience ecosystem has over 20 specialized tools, according to BCG data. Apart from dashboards that capture suppliers’ real-time performance on key indicators, state-of-the-art systems offer predictive analytics to identify potential risks. Larger organizations use cloud-based platforms so their business units can share supplier information and risk-assessment data as well as best practices and learnings.

Externally, many leaders have realized the need to collaborate with peers as well as governmental and non-governmental organizations, particularly to increase the awareness of ESG issues in business ecosystems. To create a sense of urgency, C-level executives should use every opportunity to communicate the importance of protecting the rights of their extended families of employees and report publicly on their successes—just as companies in several industries have traditionally done in the case of workplace safety and health issues. Being open about the challenges they face improves the credibility of the steps they take to tackle ESG issues.

It’s high time companies created more transparency around their global supply chains, displayed more accountability about attaining ESG objectives, and collaborated effectively to tackle those issues. Some are showing the way. They’ve laid out their expectations from suppliers in terms of labor rights, working conditions, and responsible sourcing practices, and struck partnerships with governments and NGOs to enforce them. Others are using blockchain technology to enhance visibility and accountability, particularly in food supply chains. Still others have integrated ESG-related factors into the performance criteria that determine senior executives’ incentive programs.

Focusing on ESG issues is no longer about merely complying with the current or pending laws or merely protecting corporate reputations and brands. In today’s world, the principle that companies should protect ESG norms while conducting business seems intuitive, inescapable, and irrefutable. It’s, quite simply, the right thing for business to do.