At a basic level, the science of global warming is quite simple. Humans have created processes that release gases which trap heat in our atmosphere and cause temperatures to rise. These are known as greenhouse gases (GHG). When gas emissions exceed removals, concentrations rise. Higher concentrations lead to faster warming.

However, greenhouse gases vary dramatically in their warming effect on the atmosphere. Of the three most prevalent gases, nitrous oxide (N2O) has the biggest effect per tonne, followed by methane (CH4) and then carbon dioxide (CO2). Fortunately, we emit far less methane and nitrous oxide than carbon dioxide.

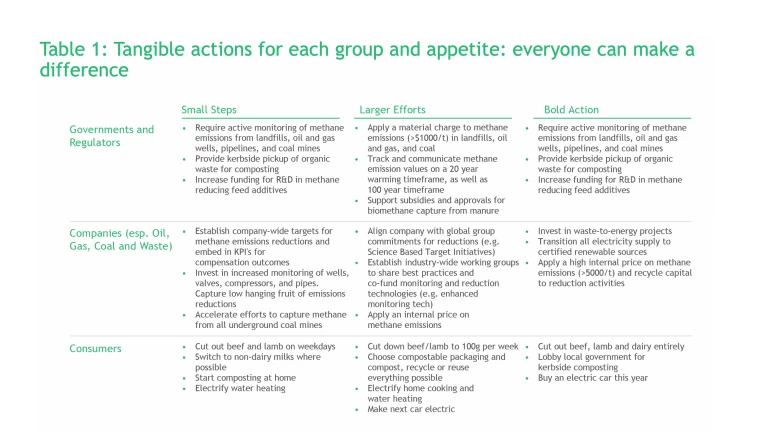

To compare apples to apples, or gases to gases, we convert each tonne of GHG to the same scale using a factor called global warming potential (GWP). GWP converts a gas to equivalent tonnes of CO2, known as ‘CO2 equivalent’. This is abbreviated as CO2-e. The GWP of methane over 100 years is 28, which means one tonne of methane has the warming effect of 28 tonnes of CO2 over a 100-year timeframe.

BAD NEWS: Methane is a big contributor to global warming

Based on a 100-year timeframe, methane emissions will be the second largest contributor to warming. In Australia it accounts for 26% of total GHG emissions, second only to CO2 at 67%.

WORSE NEWS: The math understates effects of atmospheric methane right now

Unfortunately, the conventional 100-year GWP approach underappreciates two very important nuances.

First, methane’s effect varies over time. In its first year in the atmosphere, methane’s global warming potential is actually 120 times that of CO2 (see Figure 1). It packs a big initial punch. Fortunately, methane is constantly destroyed through natural processes. So, a tonne of emissions today will only have 84 times the effect of CO2 over 20 years, and the effect drops to 28 times over 100 years. If we focus on our 100-year future, 28 is an appropriate GWP. But, it understates the immediate effects.

Second, the warming happening today is a function of the concentration of gases in the atmosphere. These are a result of hundreds of years of activities. Today’s emissions will affect the next 100 years, but today’s warming is a result of the last 100+ years.

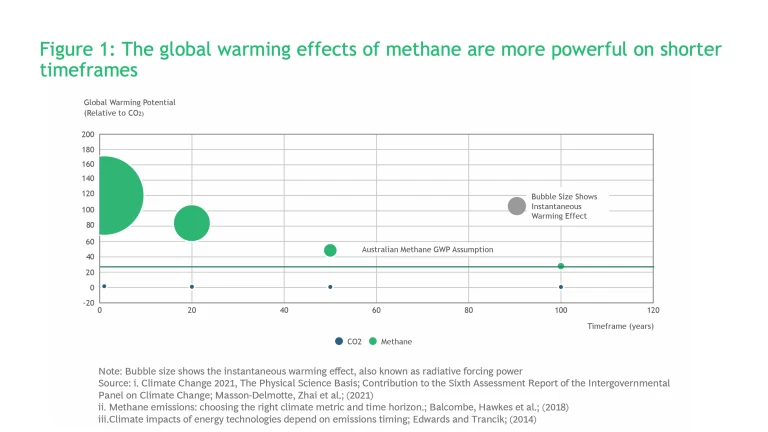

Since 1900, atmospheric concentrations of methane are up ~1 part per million (ppm), or ~120%. CO2 concentrations are up ~120ppm, but only 40% relative to 1900 levels (see Figure 2).

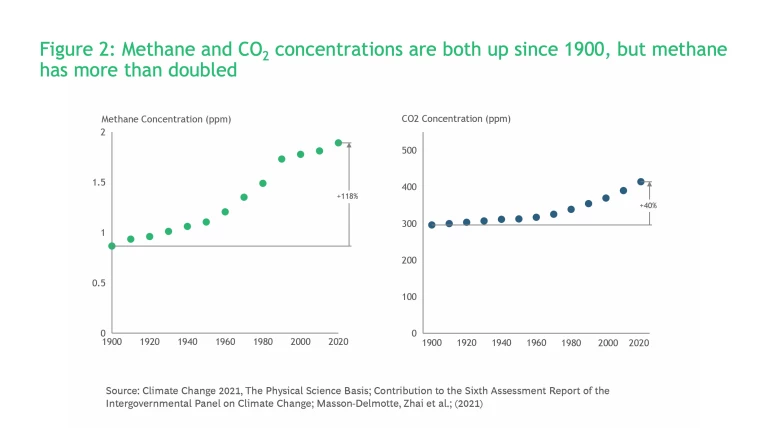

Let’s combine these effects. When the concentration of both gases is adjusted for different timeframes, applying a GWP of 120 to a 1ppm increase in methane concentration predicts an effect as powerful as a 120ppm increase for CO2 (see Figure 3).

Essentially, human contributions to today’s warming come as much from methane as from CO2. Focusing on the 100-year timeframe means we have missed the current, more powerful effects of methane – until now.

THE GOOD NEWS: We have solutions ready to go

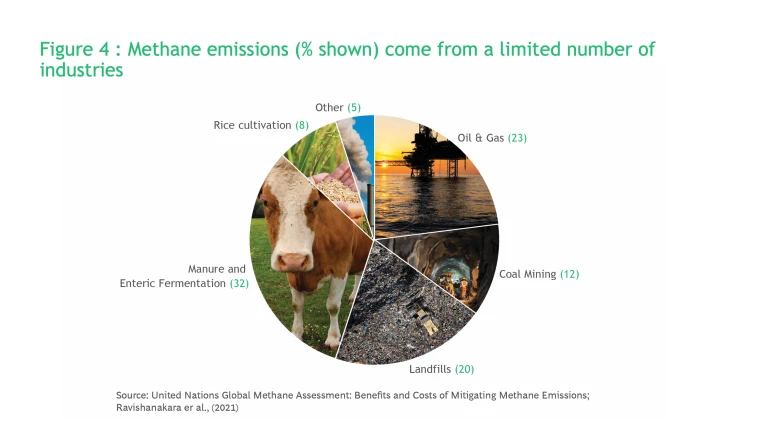

Given the immediate impact of methane emissions, we need to reduce them – and fast. Methane emissions caused by humans come from a small number of sectors and sources: agriculture, fugitive emissions from energy production, and waste (see Figure 4). We can take a targeted approach to solving the problem, and the good news is that many solutions already exist in these sectors. They will require investment and effort but are mostly proven and straight-forward to implement.

In agriculture, we need to reduce emissions from beef, lamb and dairy as much as possible. In Australia, where meat consumption is three times the global average, moderation is a good start. In developing countries, this could be more difficult. So, we’ll need to rely on a range of solutions, such as:

- Concentrating the storage and treatment of manure so that the methane can be captured and used directly in power generation and heating. Methane as a biogas is already reaching commercial scale in parts of the United States.

- Introducing new technologies – food additives, vaccines, breeding, wearables – to reduce methane release on farms: For example, a small amount of certain seaweeds in feed can reduce methane emissions by 80%.

2 2 How necessary and feasible are reductions of methane emissions from livestock to support stringent temperature goals?; Reisinger, Leahy et al.; (2021) FutureFeed

Red seaweed (Asparagopsis taxiformis) supplementation reduces enteric methane by over 80 percent in beef steers; Roque, Kebreab et al.; (2021)3 3 www.future-feed.com; (2023) , a joint venture between Australia’s science, agricultural and corporate players, is already commercialising this technology in a global effort. - Introducing the System of Rice Intensification (SRI) with alternative wetting and drying techniques to replace flooding: Studies show SRI can lead to a 40 to 70% reduction in GHG production as well as a 35% decrease in water use and material increases in yields.

4 4 Pattern of methane emission and water productivity under different methods of rice crop establishment; Suryavanshi et al.; (2012)

In energy production, we need to address oil and gas, and coal. Oil and gas operators need to find and stop fugitive methane leaks in wells and pipelines, with the added benefit of increased revenue from gas sales. The International Energy Agency (IEA) recently estimates that more than half the investment needed to reduce fugitive methane would be fully paid for by the value of the gas captured and sold – good for emissions reduction, good for business.

For coal, the story is more nuanced. Metallurgical coal is an essential input to steel production and will be required for decades to come. Unfortunately metallurgical coal mines tend to release a lot of methane. Where possible, methane should be drained from coal seams prior to mining and burned for energy. This is particularly effective in underground mines. Ideally, new metallurgical coal mines would be underground. Thermal coal, on the other hand, results in methane emissions from open cut mining in the first instance and CO2 emissions when it is burned for power generation. The most sensible environmental option is to reduce thermal coal generation as much as possible.

In waste and landfills, we need to start by generating less organic waste in our food systems and homes, compost where possible, and send less to landfills. And, we need to cap landfills, capture the methane they produce and burn it for power generation. Again, this has benefits for energy generation and for our air quality.

MORE GOOD NEWS: We can turn the tide!

Since methane is constantly destroyed through natural processes, it is possible to turn the tide. Estimates from 2008 to 2017 show that methane emissions exceeded losses by ~5%. So, if we reduce human-generated methane by 10%, we could stop the growth in atmospheric methane concentrations. A reduction of 30% should put us on a genuine downward path. In the best global warming news we’ve had for a while, acting to reduce methane now has the potential to buy years for us to do the harder work needed to reduce CO2 emissions.

Quite simply, our actions on methane between now and 2030 could be the most important contribution we make to turn the tide on global warming.

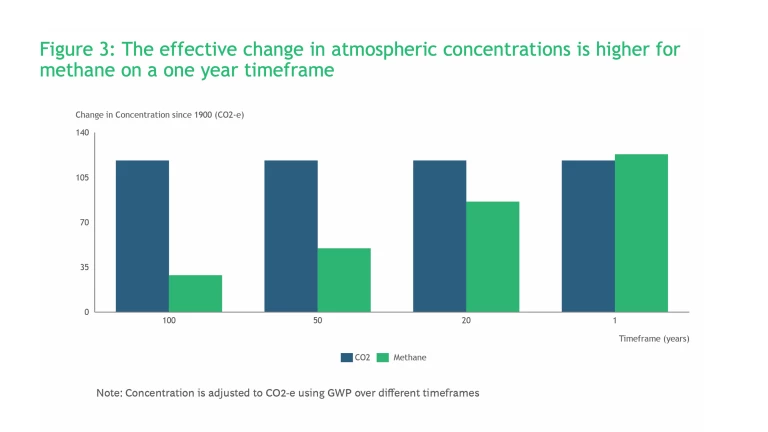

We all have a part to play:

- Governments and regulators need to make good on their promises in the Global Methane pledge. They will need to accelerate efforts to put a price on methane emissions, using the carrot of financing for abatement activities, or the stick of taxes and charges. A recent example is a charge of ~$1000 announced recently by the United States.

6 6 Inflation Reduction Act 2022, Sec. 60013 and Sec. 50263 on Methane Emissions Reductions; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; (2022) And, governments should consider whether to increase the weight placed on methane emissions in their own GHG reporting and reduction policies. - Oil and gas, coal, and waste companies can address the low hanging fruit by stopping fugitive emissions and converting them directly to sales gas or energy generation. At the same time, they need to start preparing for increased action from regulators and increased scrutiny from customers.

- Consumers can reduce their beef, lamb, and dairy consumption, and compost where possible. Every little bit matters. The brave may want to go cold turkey, literally and figuratively, but going meat free, even for 2 days a week, pushes us in the right direction. Consumers also have increasing opportunities to buy more sustainable beef and dairy that has been produced with methane-reducing feed additives. Finally, moving to lower emission electric reduces demand for oil and the related fugitive emissions.

Bold action is required globally. However, resources and circumstances vary dramatically. We encourage everyone to at least start with small steps, on the way to bold action (see Table 1).