Human progress depends not only on a handful of exceptional individuals with breakthrough ideas, but on the broader array of people who help realize those ideas by keeping the engines running and greasing the wheels of innovation . An essential ingredient in this mix is migration, the blend of talent that populations drawn from beyond a country’s borders can provide—a combination of brain power and brawn, genius and common sense, and expertise and fresh perspectives. Countries and cities that optimize their migration mix for economic potential can reap significant competitive advantage, now and in the decades ahead.

In this article, excerpted from the

full report

, we present a three-factor framework that public leaders can use to stimulate economic growth through migration policy. BCG’s Global Talent Migration Index (GTMix) describes the elements of a winning migration mix—one that correlates squarely with greater productivity and innovation, as well as with public acceptance of immigrant workers. This novel, research-backed framework can help policymakers understand the current state of their migration mix, benchmark their standing relative to other countries, and ultimately design policies that will make their economy more vibrant, more innovative, and more

resilient

.

Migration Policy Typically Focuses on the Wrong Elements

Much of the public discourse on migration in advanced economies focuses on managing immigration reactively rather than proactively shaping it. And most countries that employ active attraction strategies focus predominantly on “highly skilled” individuals. (We put quotation marks around “highly skilled” to underscore the conventional, relatively narrow application of this term—people with advanced degrees, extensive business or technology experience, or other prestigious credentials.) Meanwhile, strategies to broaden and enrich the migration mix or to expand, reattract, or otherwise engage with a nation's own emigrant network are seldom part of the conversation.

Although this standard approach is ostensibly meant to fill specific talent gaps, it ignores the sheer volume of human power needed to reverse widespread labor shortages, today and in the future, as the populations of advanced economies age. Moreover, it fails to meaningfully connect countries to the breadth of perspectives, skills, and knowledge available worldwide and thus misses out on an opportunity to foster innovation. The innovation boost that migration can provide is especially valuable, given that innovation efforts across diverse fields have yielded diminishing returns over the past several decades—despite greater investment.

To unlock this untapped potential, a country’s migration strategy must define the ideal migration mix for its needs, and it must create a plan to integrate and engage migrants. Although ample practical guidance is available on the latter point, comparable guidance on the former is lacking in popular discourse.

Our report aims to fill the gap between research and policy practice, sharing not only what “good” looks like, but also offering tactical direction on how to bring “good” to life.

Introducing the Global Talent Migration Index

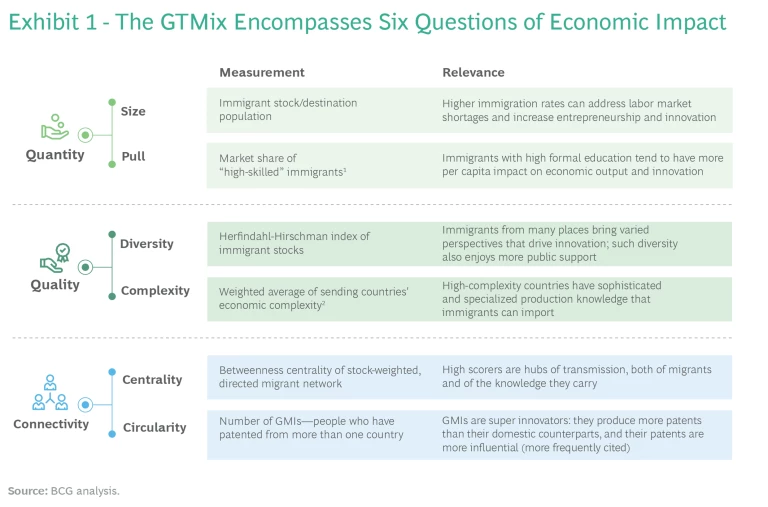

We leveraged extensive theoretical and empirical research to develop the Global Talent Migration Index (GTMix), a new tool to help countries assess and shape their migration mix. The GTMix measures value-driving features that a country’s current policies may be overlooking across three core factors: quantity, quality, and connectivity. (See Exhibit 1.) Public leaders can apply the index to evaluate the economic potential of their migration mix today, gauge the impact of past policies, and design a forward-looking migration strategy for growth and innovation.

Quantity. This factor has two components: the total number of international workers that a country brings in (size) and the global share of highly educated immigrants it attracts (pull). Overemphasis on attracting the highly educated ignores the well-documented and widespread need for other skills essential for a well-oiled economy—nurses, technicians, auto mechanics, construction workers, farmworkers, and a host of other vocational tradespeople. For this reason, high scores in both pull and size are positive.

Research shows that, beyond filling job vacancies, migrants of varying educational levels help fuel innovation and start businesses of their own at rates that exceed those of native workers. Immigrants make up roughly 15% of workers in the US but account for 25% of entrepreneurs and 25% of inventors. US-based tech and retail giants eBay, Kohl’s, and Instagram, started by immigrants from France, Poland, and Brazil, generate billions in annual income and tax revenue and employ tens of thousands of people.

Furthermore, rather than displacing or undercutting native workers, blue-collar immigrants propel domestic talent into higher-paying jobs. Event studies have consistently shown that short-term labor market crowding from an influx of new immigrants had no negative impact on native worker employment after ten years. In fact, there is evidence that increasing the size of the immigrant population leads to greater workforce participation of native women.

Quality. This factor consists of two subfactors: diversity and complexity. Diversity reflects the heterogeneity of immigrants’ national origins, which in turn reflects different ways of thinking that fuel novelty and creativity. Researchers have found a statistically significant correlation between greater variety of origins in a country’s immigrant population and increased long-term income levels and productivity; in more economically advanced countries, that correlation extends to innovativeness as well.

Complexity involves the extent to which immigrants import advanced expertise in productive work, such as agriculture, recycling, or new product development. Migrants transmit specific knowledge of best practices from their homelands around the world—whether it comes from direct expertise or simply familiarity with their home economy’s industries. In fact, research shows that immigrants from countries that are advanced in certain industries boost the productivity of those industries in their receiving countries. For example, migration between Tanzania and Kenya helped to grow the former’s soap industry. Similar links have been shown between Chilean emigrants in Sweden and the advancement of Chile’s paper products industry.

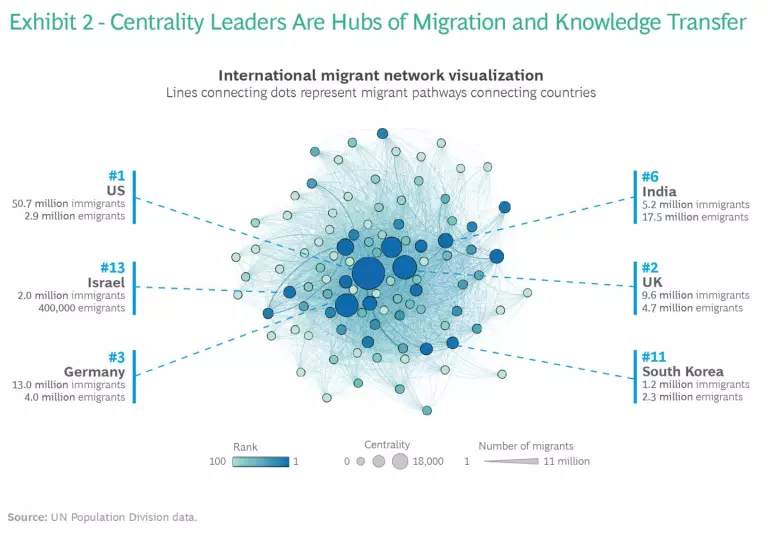

Connectivity. Connectivity gauges the extent to which a country recognizes the value of both immigration and emigration as ways to access global knowledge. It is composed of two factors: centrality, the degree to which a country is a hub in the global migrant network; and circularity, the extent to which international inventors —immigrants and return emigrants—pass through the country. (See Exhibit 2.)

Many people view emigration as a loss of intellectual talent, or a “brain drain.” Although “brain drain” (as in the loss of doctors or other essential workers) can be a real concern, the notion that countries generally lose knowledge when educated workers emigrate is misleading. Research shows that emigration actually produces a “brain gain,” by connecting sending countries to the aggregate “global brain” and the global economy. For example, after the 2011 Greek financial crisis, entrepreneurial migrants returning home to Albania drove the agricultural sector’s transition from subsistence to commercial, boosting wages and expanding job opportunities for non-emigrant Albanian workers. In the same vein, inventors see major quantitative and qualitative boosts in patenting (as measured by frequency of citation) after working in different countries and when teaming with other global mobile inventors. The most recent patent from Impossible Foods, the Silicon Valley unicorn, credits 11 inventors who have worked in or hail from such countries as Canada, China, Iran, Russia, Singapore, Spain, and the UK.

In addition to contributing to gains in productivity and innovation, migration—both inward and outward—expands the sending and receiving countries’ access to markets and increases their trade. This is particularly true in the case of migration pathways between countries with less established institutions or with less cultural commonality. For example, migrant networks between Spain and countries in Africa have had a greater impact on increasing trade than migrant networks between Spain and Latin American countries.

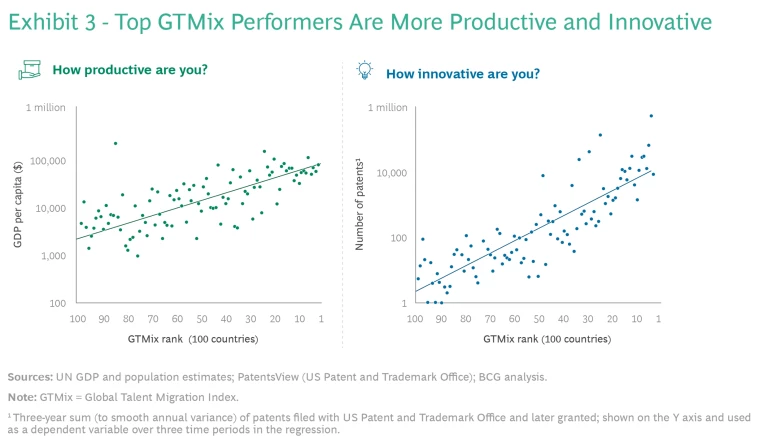

Evidence of Impact. The three core factors—quantity, quality, and connectivity—and their components independently drive economic value. Furthermore, a country’s aggregated GTMix score correlates significantly with productivity and innovation. (See Exhibit 3.) Specifically, a ten-point improvement in index score translates, on average, into 21% higher GDP per capita and a 40% increase in the number of patents that the country produces (after controlling for income, size, and other country-level differences). There is also a strong correlation between GTMix performance and societal acceptance of immigrant workers.

How the Nations Rank

The GTMix uses data on migration, education , economic complexity, and patents to assess countries’ performance in each of the three factors and their subfactors. No country can maximize its scores in all six dimensions, nor should it necessarily try to do so. Nevertheless, the framework gives policymakers a way to step back and view their migration mix through an economic lens, examining metrics that they previously either didn’t study or didn’t see in aggregate, to identify gaps and opportunities.

Notable Performers, Overall and Over Time. Countries that rank the highest across all dimensions—size, pull, diversity, complexity, centrality, and circularity—have migration mixes that deliver the most positive economic potential. In an analysis of 100 countries in 2020, the US earned the top spot, followed by Germany, Australia, and the UK. Japan, China, and India ranked 21st, 32nd, and 51st, respectively. (See Exhibit 4.)

One especially valuable aspect of the GTMix is that it allows policymakers to assess countries’ performance over time. Although the top ten spots have seen no new entrants over the past 20 years, Germany and France (for example) have followed noticeably different trajectories within it. Meanwhile, outside the top ten, five East Asian countries—Japan, South Korea, Singapore, China, and Malaysia—have gained substantial ground (moving up 6.4 places, on average, since 2000), as has Saudi Arabia (up 6 places). Despite ranking lower, a number of emerging players have advanced rapidly since 2000, including Indonesia (up 51), Sri Lanka (up 34), Thailand (up 28), and Qatar (up 27).

BCG Henderson Institute Newsletter: Insights that are shaping business thinking.

Performance by Factor. Countries may achieve a high GTMix ranking in different ways. Every country that ranks near the top overall leads the pack in some dimensions while scoring somewhat lower in others. The US and Germany earned stellar scores in three criteria (pull, centrality, and circularity), while Australia, Sweden, and Israel achieved their high overall scores by ranking in the top 15 across five of the six criteria. Conversely, despite ranking outside the top 20 in five of the six criteria, Norway and Denmark won spots in the top 20 overall, thanks to their high diversity scores.

Read more

GTMix and Integration. Immigrant integration is critical to translating the economic potential of a high-scoring migration mix into positive results. By plotting scores from the Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX), which reflects the effectiveness of countries’ integration policies), against GTMix scores, we can see which countries are most primed for success. Migration mix and integration policies are clearly correlated, yet only one country in the GTMix top 10—Canada—also ranks in the top MIPEX tier. The US and Australia have less-than-optimal integration policies, and Germany, the UK, and Switzerland have even more room for improvement in their integration measures if they want to fully realize the potential economic benefits of their migration mix.

BCG’s GTMix and its underlying principles can help policymakers identify the spectrum of assets that migration inflows and outflows offer to fuel a resilient and innovative economy. This new framework encourages public leaders not only to compete for “highly skilled” workers, but also to attract and invest in building a large, diverse immigrant population and a well-connected emigrant diaspora. The full report shows how leading countries have historically improved across the six dimensions that the index assesses, with specific examples of standout performers and the national policies and programs behind their success.

Amid intensifying labor shortages and innovation slowdowns, the value of talent migration is perhaps greater than ever. As public leaders seek new ways to bolster economic prosperity, the principles behind BCG’s GTMix reflect one basic truth: a country’s blend of talent—brains and brawn—is the fundamental source of its human progress. It’s time for countries to design strategies to broaden this mix, for the benefit of all.