Intense competition, volatile capital markets, and investor scrutiny are putting pressure on technology companies to constantly review and adapt their corporate strategies . This process must include rethinking their operating models more often than they have in the past—and more often than most think necessary. That’s because a static operating model in today’s environment is likely to yield static growth, at best. Leaders must ask themselves how to reshape the organization’s operating model around its evolving digital strategy to ensure success and resilience.

In our work with two dozen industry-leading companies, we have learned that to continually evolve the operating model, a company needs to take three steps: define its strategic priorities, evaluate whether central or local governance will create the best competitive advantage, and adapt the most critical business processes accordingly.

Define Strategic Goals

There is no single “right” operating model for technology companies. Each organization’s model will depend on its strategy, which means that it needs to be very clear about what it wants to achieve for its customers, how it will differentiate itself to grow and compete in the marketplace, and which metrics it will use to measure performance.

For technology companies, this is an especially critical and urgent question given how rapidly many are evolving through different phases of growth in a hypercompetitive market. While a large number of companies are still in the startup phase, some have begun to scale up proven offerings. Meanwhile, highly successful companies have attracted sufficient investment and attention to reach unicorn status, and a rare few are so established that they’ve begun to dictate the terms of their market.

In our experience, the choice of operating model is often linked to a company’s growth stage. For example, young companies often focus on quickly adapting their offerings to customer needs in order to ensure continuing market fit. Established companies often prioritize efficiency and aim to leverage economies of scale.

Leaders must ask themselves how to reshape the organization’s operating model around its evolving digital strategy to ensure success and resilience.

The first step in choosing an operating model is to answer questions that will clarify the company’s overarching strategic goals. Questions that technology companies need to ask include: How is the company pursuing growth? Is it looking to scale quickly across the globe or to expand in one or a few core markets? Does it aim to beat local competitors by leveraging global scale? Or to beat global competitors through a tailored, local approach? Is the target market evolving and expanding?

Central Versus Local Governance

The second step in evolving the tech operating model is to determine how centralized or localized the operating model can or should be given the company’s products, customers, and competitive environment. Fundamentally, the issue is whether the source of a company’s competitive advantage is economies of scale or customization.

That said, the fact is that while a few companies have operating models that are either extremely centralized or extremely localized, most pursue a middle path. Even those with the most standardized processes have some processes that are customized to some degree to local markets. Regularly comparing the benefits of localization with the benefits of centralization is important for success.

A few questions to keep in mind include: Are the company’s products intended to be the same across different markets or segments? Do customers on the demand side have similar characteristics, transaction patterns, and needs? Likewise, do customers on the supply side (such as Airbnb hosts or Uber drivers) have similar characteristics, patterns of behavior, and needs?

Centralized Global Players

At one extreme, companies such as Facebook, Amazon, Uber, and Twitter roll out the same products globally without a lot of customization. Although they want a presence in many markets, they optimize products only for key markets and are willing to “lose” in others. As one senior technology executive explained, “We choose to centralize most of our functions to drive innovation, efficiency, and speed to market. But we had to make tradeoffs. We lost some customers because of our slow response to local market dynamics.”

There is no single “right” operating model for technology companies. Each organization’s model will depend on its strategy.

A centralized approach is often a smart way to “speed to global growth” and create cost-efficient scalable products, but it’s not right for penetrating markets that are hyperlocal (and fast growing, such as Indonesia and India). Uber, for example, does little to adapt its Western-centric business model, based on four-wheel-vehicle ride hailing, to regional markets. Yet heavily congested markets such as Indonesia rely more on two-wheel modes of transport, such as motorbikes.

Hyperlocal Players

At the other end of the spectrum are players whose competitive advantage derives from being hyperlocal. “We strive to be as local as possible,” said a senior executive at a leading Asian super-app, “by adopting a highly country-centric approach to our commercial functions. We have a high conviction that the way to win is to be closest to what the specific market needs and solving its specific frictions.”

For example, some of the local ride-hailing players in Asia focus on building a deep understanding of each market and customizing products accordingly to penetrate deeper and increase their share of wallet. These companies have managed to beat global competitors in their local markets precisely because they customized their offerings for two-wheel modes of transport, including the way they engage with drivers and merchants and the way they localize their pricing strategy .

As successful as this approach can be, there are pitfalls. In general, a company pursuing a localized strategy should avoid entering a new market if its characteristics are not well understood or if they are very different from those of the company’s core market. One major risk for hyperlocal players is getting stuck at the local level and becoming unable to make gains in global markets.

Assessing the Tradeoffs

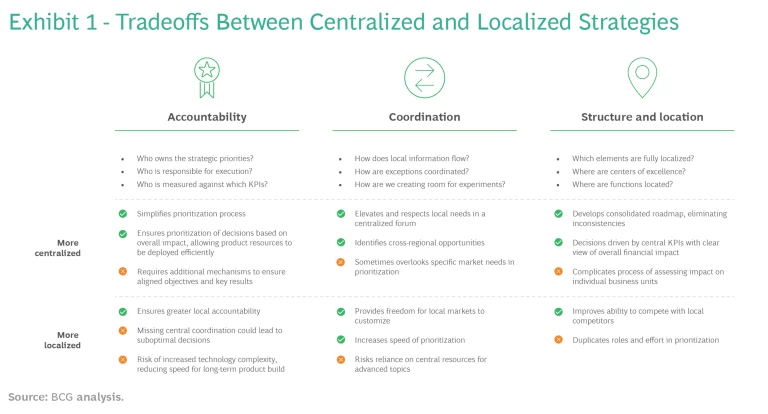

Whether a company pursues a centralized or a localized strategy, there are standard questions and tradeoffs around issues of accountability, coordination, and structure and location. (See Exhibit 1.)

Accountability. Questions to ask include: Who owns the strategic priorities? Who is responsible for local execution? And who is measured against which KPI? Most organizations with centralized governance models benefit from simpler processes, better alignment across teams on incentives, and easier scalability. But they lack the agility to respond quickly to fast-changing local market dynamics, which players with local autonomy and accountability are able to do.

Coordination. How does local information flow into companywide processes? How are customization efforts coordinated among different markets? How do experimentation and innovation occur? (See “Innovating Beyond the Core.”) Centralized organizations benefit from integrated and standardized processes that allow them to coordinate across markets and share best-in-class capabilities. But again, they are less able to react quickly to local market needs. When coordination is more localized, companies can more efficiently adapt to a local market’s specific needs, but at the expense of scale and often of complexity.

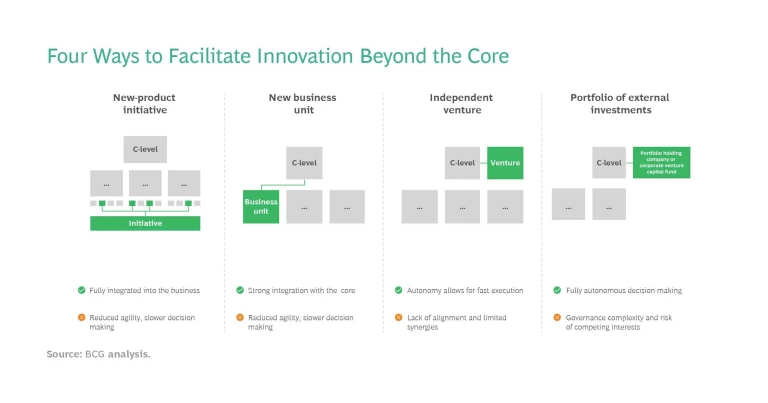

Innovating Beyond the Core

- Launch an initiative with a small, cross-functional team using shared resources to experiment with a very new, relatively risky innovation. This approach is appropriate when business units want to allocate some resources to experiment and learn but don’t want to overcommit or disrupt the day-to-day business.

- Establish a new business unit. This can be effective when the innovation has already demonstrated value and is highly synergistic with core operations.

- Create an independent, external venture. This is a good choice when the innovation has significant potential but is not strongly linked to core operations. It promotes agility and speed (for example, to capture a first-mover advantage) by freeing the venture from limiting factors in the corporate environment (such as governance processes and rules and regulations that are not fit for purpose). As the majority owner of the venture, the company still exercises control, but it functions as a shareholder rather than the operator of the venture.

- Make external portfolio investments. Sometimes it’s advisable to make calculated bets through minority investments. This approach to building an innovation portfolio is appropriate for highly uncertain initiatives involving unproven technologies.

Structure and Location. Which offers or services are fully localized? What elements of the organization are embedded into centers of excellence? When it comes to branding, for example, high-level messaging might be centralized, while local teams are allowed to adapt the tone to suit the market (as long as it’s in keeping with the overarching strategy).

Centers of excellence can define strategic imperatives and draw on talent and expertise from across the enterprise, but they can easily overlook the needs of specific markets. In contrast, localized organizations focus on those local needs and on making quick decisions to satisfy them. But to do so they must duplicate organizational structures across markets, increasing overhead and driving up costs. Choosing the locations of centers of excellence wisely (such as by moving them close to core markets or to lower-cost regions) can mitigate some of these issues.

Subscribe to receive the latest insights on Technology, Media, and Telecommunications.

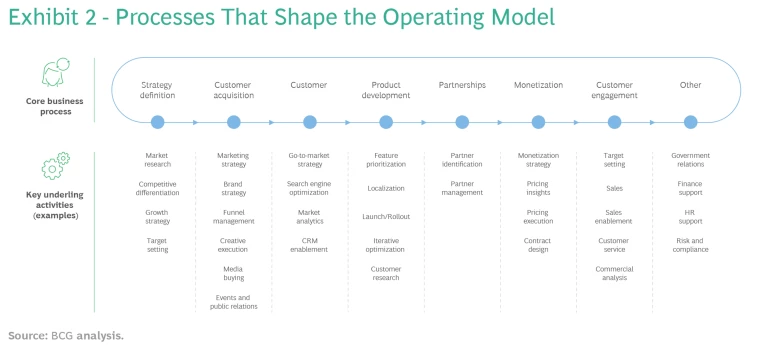

Adapt Key Processes

The secret to reshaping an operating model and maintaining efficiency is identifying the core business processes that should be adapted in order to reach the company’s strategic goals. (See Exhibit 2.) This was an important lesson for the COO of a global digital marketplace: “When we first launched in China, we were unsuccessful because we tried to adopt a plug-and-play approach, taking what worked on the Western side of the world… We ended up setting up an independent business unit to cater to the needs of the China market.”

The need to carefully adapt processes is nowhere more acute than when determining whether and how to differentiate products. For each one, companies must decide which features to keep constant across markets in the interest of efficiency and economies of scale and which features are worth tailoring for certain markets. Even a global company such as Twitter, with its very centralized approach to determining product features, has set up a formal forum where regions pitch new products or features. These are then prioritized according to the results of impact analysis and other criteria.

Another highly centralized global tech company that we worked with was consistently losing market share to local companies in growth markets. Recognizing that the product organization had few if any mechanisms for taking local feedback into account, the company piloted a multidisciplinary team to bring local and global teams together. Product feature prioritization accelerated significantly under the pilot, and adaptations to local markets were delivered faster. After rolling out the new operating model globally, the company’s performance against local competitors vastly improved.

Getting an Implementation Underway

It almost goes without saying that senior leadership is absolutely essential to changing the mindset of the organization. Change is hard—and organizational and cultural changes are especially difficult. It takes strong commitment from leaders to keep pushing the company toward its goals against internal resistance. Some recommendations for leaders include the following:

- Forget the big-bang approach. Start small and prioritize by identifying parts of the organization where the impact of change will be high and resistance is likely to be comparatively low.

- Don’t get bogged down in detailed design early on.

- Cluster like-for-like processes together to create some consistency in operations and decision making.

- Demonstrate that change is necessary using real-life experiences of the company that highlight frictions and consequences (such as slow decision making and poor customer outcomes).

- Involve all stakeholders in the process redesign, workshopping how processes might be improved. This should include both top-down and bottom-up perspectives.

- Run pilots, monitor change, and share success stories as part of the rollout to build enthusiasm and momentum.

Strategies evolve and so too must operating models. This has never been truer than it is today, given the pace of technology change and disruption. But that reality doesn’t make the challenge any easier from an organizational and cultural perspective. Change is hard—and it always will be. By embracing the need for continual reinvention, leaders can keep their companies on the cutting edge and always well positioned for growth.