Fundamental advances in life sciences are underpinning biomedical sector growth and innovation globally. Australia is better positioned to participate in this growth than many might expect. In recent years, the local biomedical ecosystem has grown rapidly, supported by world-leading scientific research, the presence of leading multi-nationals, and distinct strengths such as Australia’s advantages as a clinical trials location. At the same time, historical constraints on sector growth, such as limited venture funding and weak commercialisation capabilities, are beginning to be overcome.

Further strengthening Australia’s health innovation sector would deliver economic growth, high-value employment, and sovereign biomedical capacity. While traditional industry development typically centres on funding large brick-and-mortar projects to support immediate job creation, government can catalyse outsized biomedical sector growth by attracting critical capabilities that will support thriving ecosystems.

This is not a pitch for governments to ‘pick winners’. Rather, it is an argument for government to lift the odds of successfully bringing local research to market by filling critical gaps in capability, particularly in areas of biomedical science where Australia has existing, world-class strengths.

The biomedical sector will be at the forefront of value in the 21st century

Flagship Pioneering, the venture building firm behind Moderna and its mRNA vaccine, dubbed the new millennium as the inception of the ‘ Biological Century ’, where continuous advances in biological technologies and understanding will create outsized value in many industries. These advances include the ability to read and write DNA/RNA as easily as we read books, and the application of AI and engineering to peel back the complexity of biological systems.

Global case studies demonstrate the economic impact that clusters of research and commercialisation activity can offer. For example, the Cambridge life sciences cluster in the UK drives ~22,000 jobs with ~AU$17 billion in revenue each year.

Australia’s biomedical sector is well placed to grow and lead

In recent years, Australia’s biomedical sector has demonstrated strength and promise. The foremost cluster of biotech and pharma activity is in Parkville in Melbourne. Other hubs of activity include Macquarie Park in Sydney and the Boggo Road precinct in Brisbane. Global success stories include Cochlear, CSL, and ResMed while smaller players like Telix Pharmaceuticals have also been among the fastest-growing ASX-listed mid-cap companies in recent years.

Several factors have supported Australia’s success so far, including:

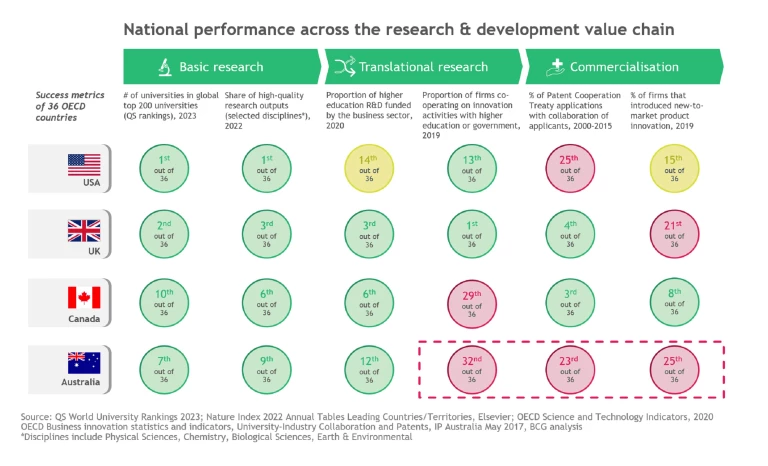

- High-quality basic research. Australia is ranked 7th out of 36 OECD countries for number of universities in the top global 200; and ranked 9th for share of high-quality research outputs (Exhibit 1). For example, the University of Sydney ranks among the world’s top 20 universities for oncology and endocrinology research.

2 2 US News, Best Global Universities, 2022. This foundation of university research provides a strong pipeline of pre-clinical and clinical opportunities for commercialisation. - Supportive regulation and incentives. Trial regulation, and research and development (R&D) tax incentives, like a 43.5% cashback per $ spent in R&D, underpin the strong growth of Australia’s AU$ ~2 billion Contract Research Organisation (CRO) market.

3 3 Arizton Market Research 2023, BCG analysis Trials have a fast time to approval (e.g., timeframe for regulatory approval in Australia is ~3x shorter than in the US and ~2x shorter than in the UK for phase 1 clinical trials)4 4 Government health departments, BCG analysis. Approximate timeframes for average clinical trial and a rigorous patient safety process. Furthermore, regulatory agencies in 2 of the largest biopharma markets (US FDA and Europe EMA) accept Australian clinical testing, making Australia attractive grounds for Asia-based CROs. - Government commitment to health R&D. The Australian government allocates 16%–22% of research spending to health, well above the OECD average of 10%.

5 5 OECD, 2016-2022, government budget allocations for R&D This stable support and funding are crucial for developing the pipeline of basic, translational, and clinical research upon which any new drug or therapy is developed.

Overcoming historical barriers to a thriving sector

As the sector has evolved, it has gradually overcome historical barriers, with two main improvements:

Increasing availability of venture funding. The availability of funding to take ideas out of the lab has improved substantially in recent years. The number of VC funds focused on supporting biomedical development has expanded, with new entrants and new money being raised, including Brandon Capital, Uniseed, and IP Group. There are also new government-backed efforts at the state level, like Victoria’s $2.0 billion Breakthrough Fund and Tin Alley Ventures, and at the Commonwealth level, like the $2.2 billion University Research Commercialisation Action Plan, which complements major sources like the Medical Research Future Fund.

Nonetheless, there is still a long way to go. Australia’s total venture capital investment as a share of GDP (0.035%) is less than one-tenth of US venture capital investment’s share (0.535%), and less than one-third of the OECD average (0.133%).

6 6 OECD, 2019 (latest data available), venture capital investments as share of GDP There are still few mature biopharma multi-nationals who have a major research presence in Australia or scout for partnerships at the pre-clinical or clinical stages (noting that CSL’s partnership with the Jumar Bioincubator is a welcome step in this direction).Improving commercialisation capability. Australia ranked 32nd out of 36 OECD countries in 2019 for translational research, as measured by the share of companies who work together with universities on innovation activities. Australia also ranked 25th out of 36 for commercialisation, as measured by the share of firms that introduced new-to-market product innovation in 2019 (Exhibit 1).

Common problems driving these low rankings include lack of integration of subject matter experts; low availability of commercialisation support; and blunted financial and reputational incentives for individuals, faculties, or universities to commercialise research out of their labs. This lack of capability leads to wasted opportunity for commercialisation and to the benefits of Australian research being realised by other countries.

However, the environment is starting to change. Cultures are shifting within universities, and students and faculty are more interested to spin out ideas with support from the institution. This interest is evident at the community level, with more active founder communities among students and researchers, and new university-dedicated funds like Tin Alley Ventures at the University of Melbourne.

Australia can support the development of thriving ecosystems by filling capability gaps

Globally, governments have typically played a role in the development of biomedical ecosystems, which have delivered long-term economic value. In Boston (USA), favourable legislation and tax schemes supported early agglomeration of industry. In Cambridge (UK), the government invested in essential infrastructure (e.g. biobanks) in the hub. Similarly, in Toronto (Canada), the MaRS Discovery District is funded with a combination of private and public funds, including government grants, tax incentives, and favourable financing arrangements. Following these examples, the continued growth of the Australian biomedical sector will need government to be at the table as a supporter, with an integrated approach across federal, state, and even local layers of government.

Traditionally in Australia, government has attempted to develop industries by providing direct industry support via co-investment in brick-and-mortar projects, grants to companies, and tax subsidies. This approach guarantees some degree of job creation. Victoria’s vaccine manufacturing plant with Moderna and NSW’s RNA pilot manufacturing facility are recent examples of this type of direct support. Typical economic assessments by government value the reliability of new jobs and local contribution, with a tendency to focus on the relative surety of economic value creation. However, this approach has much lower chances of generating truly outsized returns. Governments have also experimented with more innovative financial support, like the Biotech Translation Fund (where the government co-invests alongside private VC investors) and the National Reconstruction Fund (NRF), with A$1.5 billion earmarked for medical manufacturing.

There is an opportunity for government to play a more innovative role by developing sophisticated, self-reinforcing ecosystems that support wider economic value. To support these ecosystems, government can address historical barriers by attracting capabilities which are lacking today. Commercialisation capability to take research from lab to patient is the limiting factor that is often overlooked for biomedical sector development. Financial investment in brick-and-mortar facilities can initially house and attract people but support to keep talent should not finish once the building is topped off. Organisations looking to access government funding like the NRF need to make a clear case for how investment can help retain the right talent and provide the right opportunities to lift the sector’s commercialisation capability.

Initiatives can include establishing partnerships with global experts and pharma multi-nationals who fill expertise gaps in Australia (like Sanofi’s partnership with the Queensland Government). It could also include facilitating collaboration to share skills and talent between academia, industry, and funders. This facilitation needs to go beyond organising conferences. It must understand the value proposition of different players and how that evolves as the ecosystem grows.

In the early 2000s, when working on the development of the Boston life sciences hub with MassBio, Dave Matheson, a BCG advisor, found the following steps crucial to facilitating effective collaboration and accelerating capability development in the Boston hub:

- Seeking feedback from MassBio’s trade group partners (e.g. hospitals, start-ups) to understand their unique value proposition

- Incorporating feedback into MassBio’s overall objectives and policy outcomes that they seek from the government

- Developing initiatives to help each player realise their value proposition (e.g. simplifying permits for pilot manufacturing in Massachusetts) and creating the conditions that allow players to drive the long-term work themselves

Targeted capability attraction should be deployed in existing areas of strength

To create a thriving ecosystem, government’s capability-building support should be invested in areas of strength which already exist in Australia. Strength can start from one of three levels – value chain, product or theme. In the biomedical sector, this translates to:

- Value chain: the full research, development and innovation (RDI) process, from basic research to translational research to clinical trials

- Products: e.g., vaccines, therapeutics, diagnostics, wearables, industrials or others

- Themes: e.g., synthetic biology, AI, immuno-therapy, and RNA therapy

One recent example of a high potential “theme” is precision oncology. In Australia, this area is currently supported by the Precision Oncology Screening Platform Enabling Clinical Trials (PrOSPeCT), a public-private partnership to bring precision oncology trials to the public.

Genuinely delivering at-scale returns and meaningful ecosystem development requires policy willingness to attract these capabilities for a portfolio of multiple niche areas (across value chain, products, and/or themes). While investments into a single area may be risky, when a portfolio of niche areas are pursued, the risks are diversified and outsized success of a few opportunities offers overall compensation.

Ultimately, innovative approaches to sector support can accelerate Australia’s biomedical industry to critical mass and fill the missing pieces of its fragmented commercialisation landscape. Ecosystem development, by attracting targeted capabilities into a portfolio of strong areas, can kick off a powerful domino effect of private and public investment and a long horizon of economic value.