This article is part of the Decoding Global Talent series of BCG and The Network, which investigates long-term workforce trends around the world.

“Realize that applicants are not ROBOTS and treat us as individuals.” That’s what a respondent to our survey said when asked about the one thing companies should change in the way they recruit people. Many others echoed the sentiment. “Be less concerned about ticking the boxes and more about the person.” “Look at people.”

For candidates, choosing a job is a very personal decision. It’s the start of an extremely impactful relationship, one that may define several—or many—years of their lives. No wonder candidates are sensitive to “moments of truth,” when employers reveal who they really are.

For employers, it’s a critical business decision. But underlying that business decision is the crucial need for people, which makes the personal preferences of job seekers highly relevant to the business. Despite a possible economic slowdown, global unemployment remains low and employers still feel the impact of the Great Resignation. It’s not easy to win over top talent, especially in high-demand fields. Increasingly, a lack of suitable people creates a bottleneck that impedes business growth—thus elevating the talent issue to the C-suite level.

Part of the problem lies in the recruitment process—how employers and candidates connect, communicate, set expectations, and make decisions. Or how they don’t. Often, employers don’t know what policies and actions will attract potential employees—or deter them. Sometimes, they may even be uncertain about how to find and recruit them.

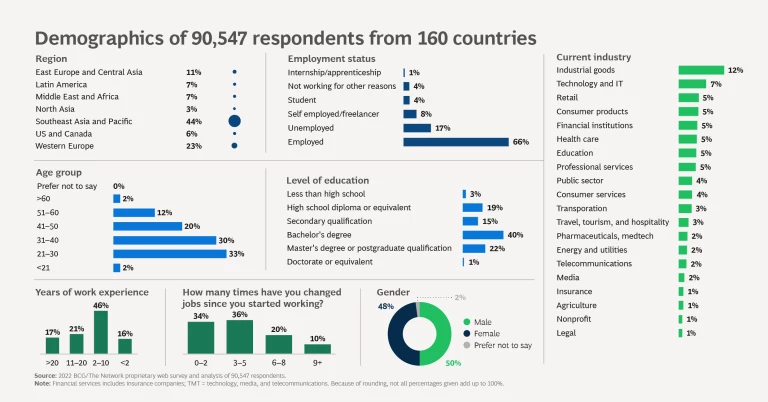

Who better to clarify those uncertainties and help companies improve their recruiting ROI than job candidates themselves? From August through October 2022, BCG and The Network, a global alliance of recruitment websites, undertook the world’s largest survey dedicated to exploring job seekers’ recruitment preferences—more than 90,000 people participated. (See “Methodology.”)

Methodology

The survey covered three main topics: prospective employees’ current position in the labor market, their preferences regarding their ideal career, and their preferred recruitment journey. In addition to conducting the survey, we collected insights from leading recruitment platforms in key talent markets.

We asked, among other things, how people see their position on the job market, what attracts and motivates them, and what they think the ideal recruitment process would look like.

Among our findings: some myths about recruiting are just that—myths.

This article reports and interprets additional survey findings and offers recruitment recommendations for employers.

The Talent Market Is Still Hot—And Candidates Know It

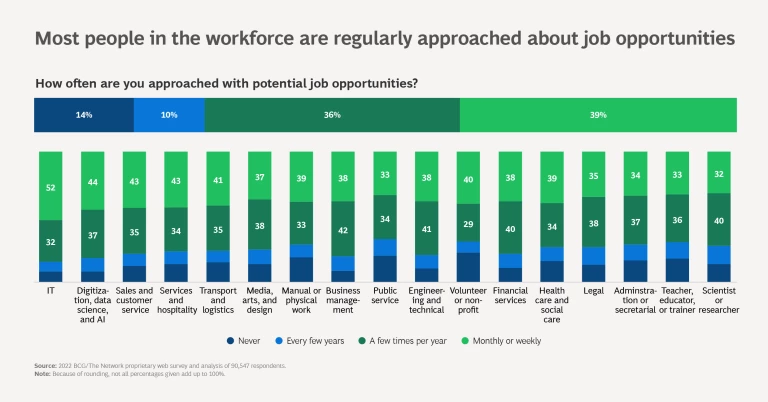

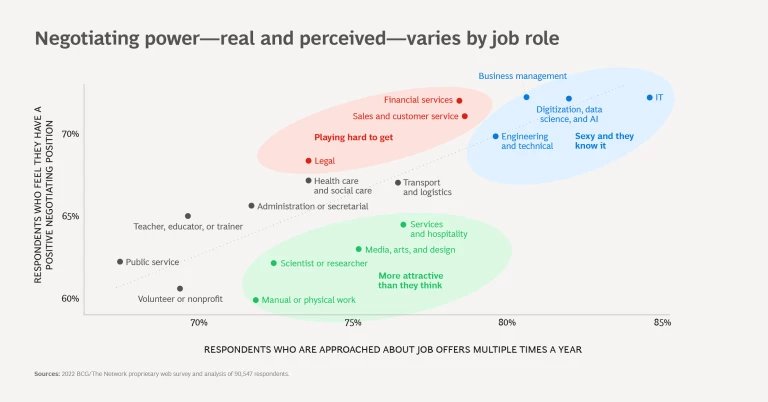

At the time of our survey, 74% of respondents said that they are approached multiple times per year about job opportunities—in fact, 39% said that they are approached every month. Even if a future recession lowers the temperature of the talent market, employers probably won’t see an abundance of talent in the short term, especially in high-demand fields. (See “Market Insights.”)

Stay ahead with BCG insights on people strategy

The most coveted people are those working in IT, digital, and sales jobs, followed closely by those in hospitality and transport and logistics. Scientists and teachers receive the fewest invitations to apply for jobs, likely because of the nondynamic nature of these fields, where tenure and long-term government contracts are common.

The outreach to potential candidates doesn’t vary significantly by location or by age group (which is good news for the many respondents who told us that they wish hiring companies would not put so much emphasis on age).

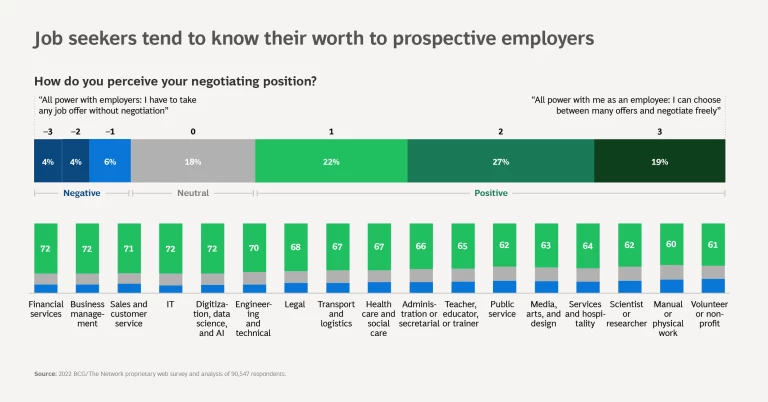

Job candidates, well aware of how many opportunities they have, tend to be confident of their value and bargaining power. Most people (68%) feel that they are in a strong negotiating position when looking for a job (that is, they believe they have more power than prospective employers). Only 14% feel that employers hold the reins in negotiations. Confidence is highest among those who work in finance, business, and sales and lowest among manual workers, nonprofit workers, and volunteers.

Being on the receiving end of multiple invitations to pursue jobs would logically seem to correlate with confidence in one’s negotiating power, and this is generally true. Candidates currently in IT, digital, and other tech fields are “sexy and they know it”: they get many invitations and consequently believe that they are in a strong negotiating position.

The correlation does not always hold, however. Many candidates in finance, sales, and law are “playing hard to get.” They believe that they have the upper hand, but the frequency with which they are contacted about job opportunities does not back up that confidence. On the other hand, service, media, science, and manual workers are “more attractive than they think.” They receive a relatively large number of invitations but are less confident about their negotiating power.

Employers need to be aware of where job candidates are coming from and should adjust their negotiation technique accordingly. With digital superstars, they may not get a second chance, so it’s best to start with a strong first offer. With other segments, employers may have more space for discussion. But one thing seems sure: candidates are less and less likely to simply accept an offer without asking for more.

What Candidates Want

People’s desires regarding jobs vary depending on where they are on their career journey. In some instances, they may take a long-term view that includes planning their career trajectory. In others, they may have a job offer on the table and a decision to make. And in still others, they may be at a beginning or inflection point, considering a job or career change.

Planning a Career for the Long Term

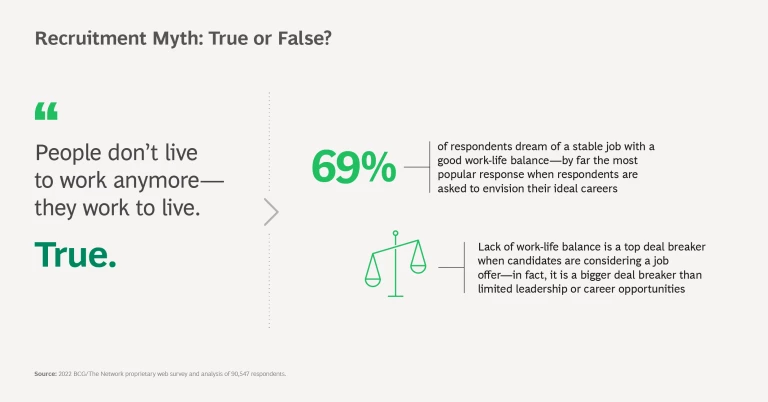

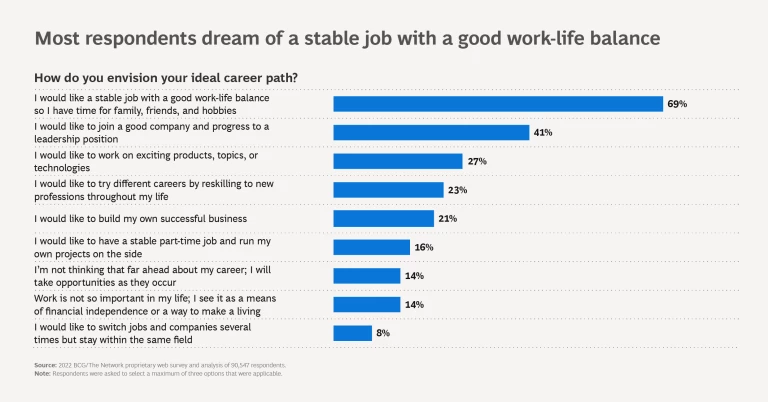

Most people don’t want to live to work anymore. They want to work to live.

Most respondents (69%) in our survey said that they desire, above all, a stable job with a good work-life balance. This preference is dominant across job roles, regions, and age groups. Career progress at a good company comes second, and working on exciting products, topics, and technologies is third.

Fewer people dream of reskilling to new careers or building their businesses.

Responding to a Job Offer

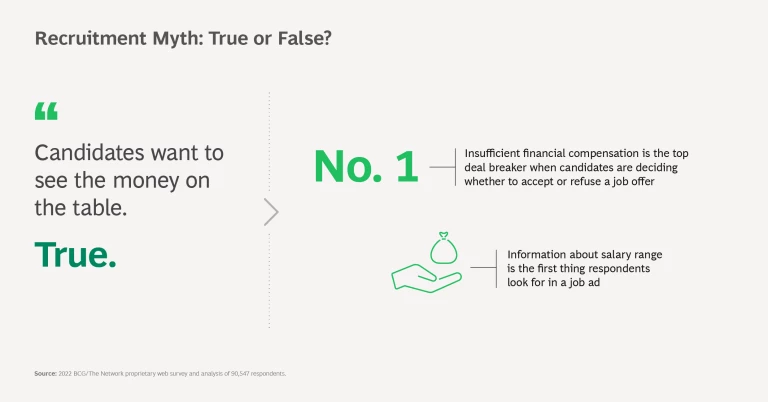

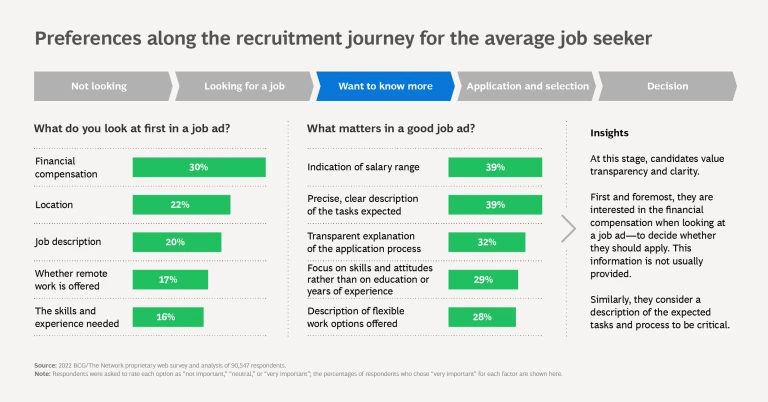

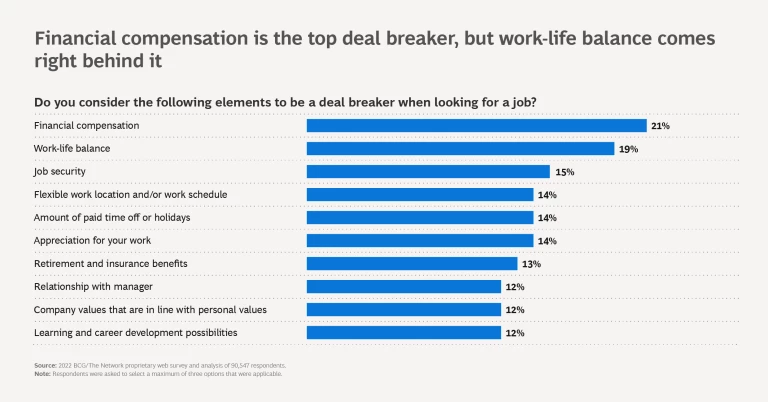

People may dream of a steady job with a good work-life balance for the long term, but when an opportunity is placed in front of them, they still look at financials first. Across regions, people who are weighing a concrete job offer usually make the financial package—salary and bonus included—their highest priority.

But work-life balance (in accordance with people’s long-term vision) ranks second behind financial compensation. And, in most regions of the world, people consider shortcomings related to paid time off and job security to be leading deal breakers.

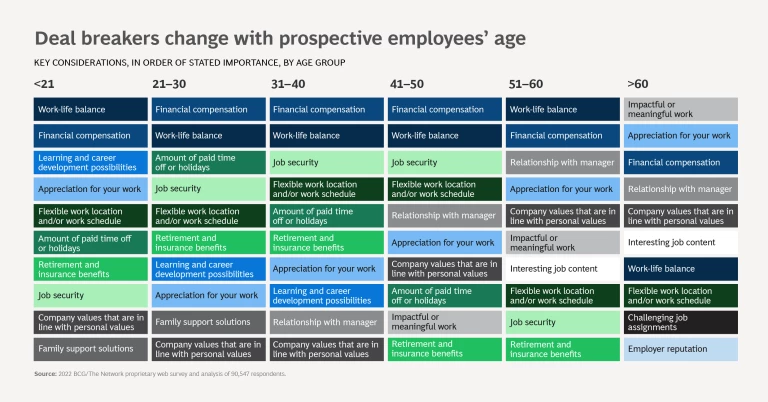

We also looked at respondents by age group. Compensation and work-life balance are generally the two top priorities regardless of cohort, but deal breakers change significantly with age:

- For the youngest generation, learning and development opportunities are very important, but this attribute gradually decreases in importance as respondents age, and respondents older than 40 don’t cite it among their top ten deal-breaking concerns overall. Although this doesn’t mean that older workers will resist learning new things if they have to, the decreasing motivation to learn may pose a challenge, given the masses of people who will need to continuously reskill and upskill to keep pace with new workplace demands for AI, sustainability, and other skills.

- Workers who are 30 to 50 years old prioritize job security and flexible work arrangements. Many of these workers have family commitments (to young children, aging parents, or both) and value flexibility in work hours and locations to ensure that they have more time to spend with their loved ones.

- Among respondents older than 60, impactful work and appreciation for their work rank relatively high— an interesting trend to consider in light of the aging workforce and the rising retirement age in multiple countries. Other factors that tend to become more important with age include relationship with a manager, company values, and interesting job content.

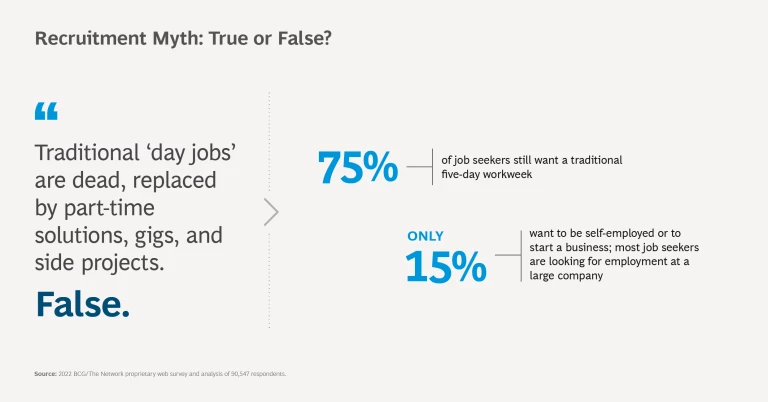

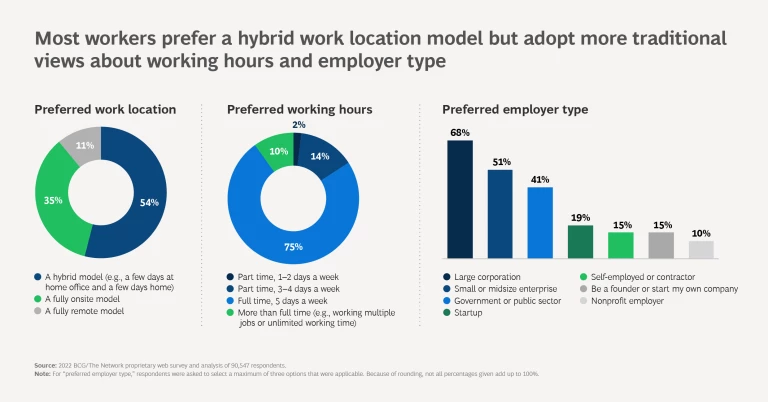

We also asked candidates about their preferred working models and employment types. Many respondents had rather traditional choices—sometimes surprisingly so. They favored traditional employers: large corporations, small to midsize enterprises, and governments. Working at startups and as part of the gig economy were less popular choices.

The majority also said that they prefer a traditional five-day workweek. Perhaps they are satisfying the appetite for flexibility that we saw in earlier surveys by taking advantage of opportunities for hybrid work, which blends time in the office with time working remotely. Hybrid work is still popular—54% of respondents favored this model—but that result represents an unexpected decline in preference from our autumn 2020 survey, in which 65% of respondents said they wanted a hybrid model that included two to four days of remote work. Further, 35% of current respondents, and an even higher share of those in Latin America and the Middle East, are comfortable with working all of their hours onsite.

Deciding on a Change

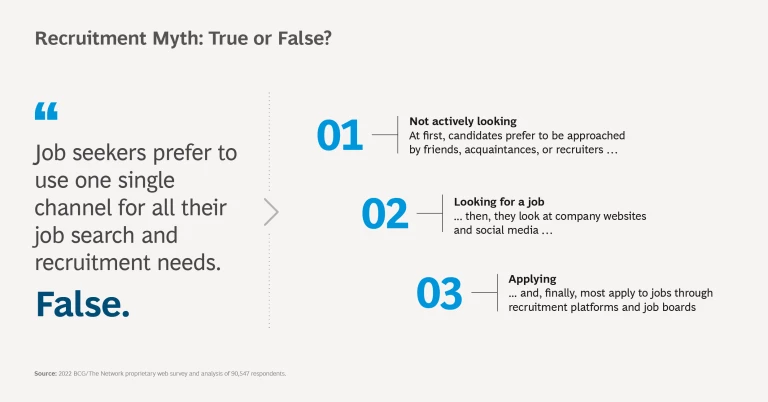

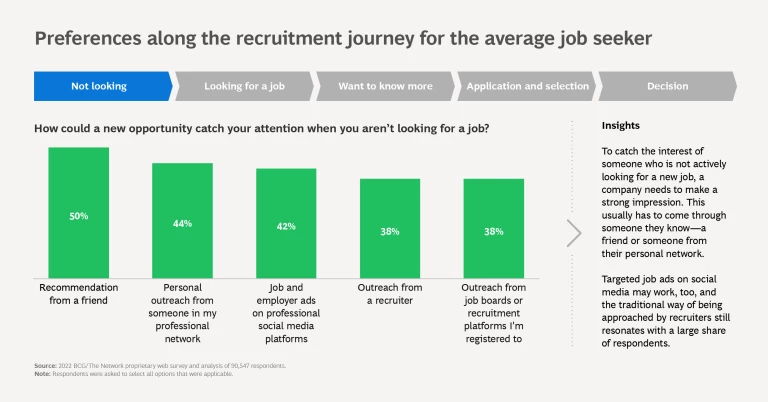

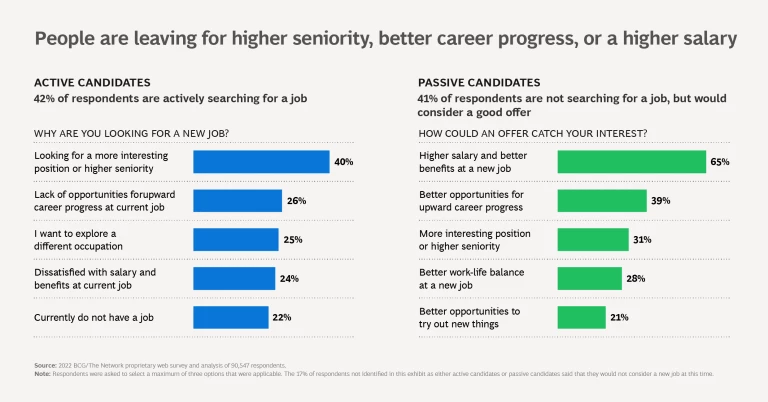

Many (42%) of our survey respondents reported that they were actively looking for a job. Many others (41%) described themselves as not actively looking but said that they’d be open to a job change if presented with a good offer.

The motivations of these actively looking and passively looking job candidates differ:

- Active job seekers care mostly about higher seniority, greater responsibility, or the chance to explore a new profession. They are motivated by the content and scope of the prospective job itself.

- Passive candidates are not necessarily uninterested in these job attributes, but to capture their attention, employers must dangle the promise of a significantly improved compensation package in front of them. A better work-life balance is also among the top five features that they say could capture their interest.

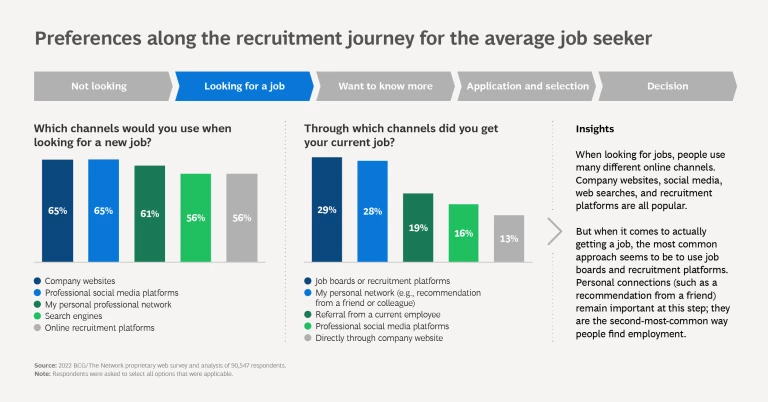

Employers need to fish in both ponds because hooking active talent alone is insufficient. Companies that can capture passive talent will have a major advantage.

How to Acquire Talent

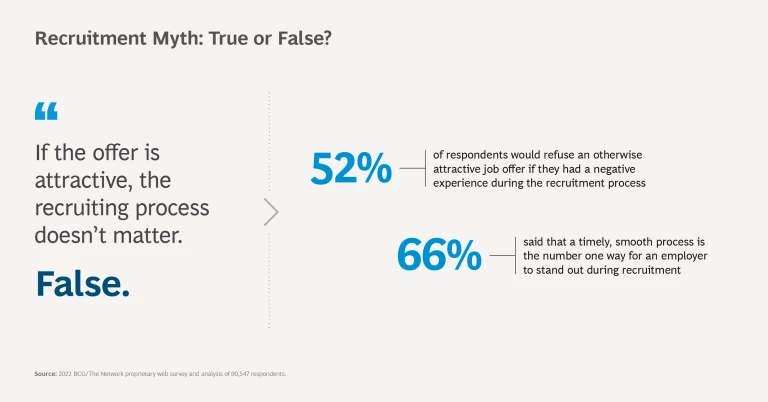

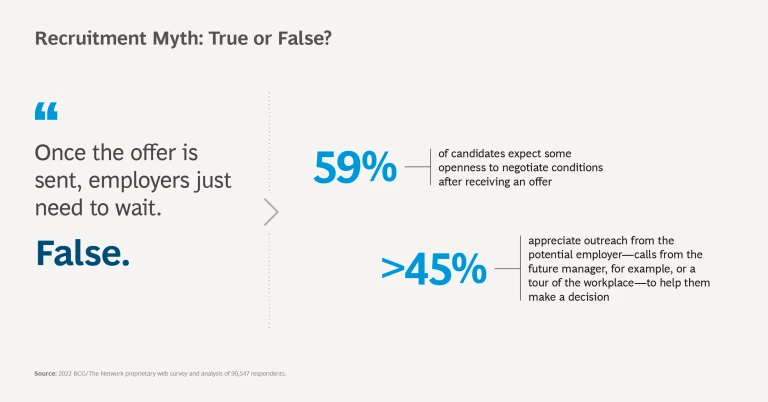

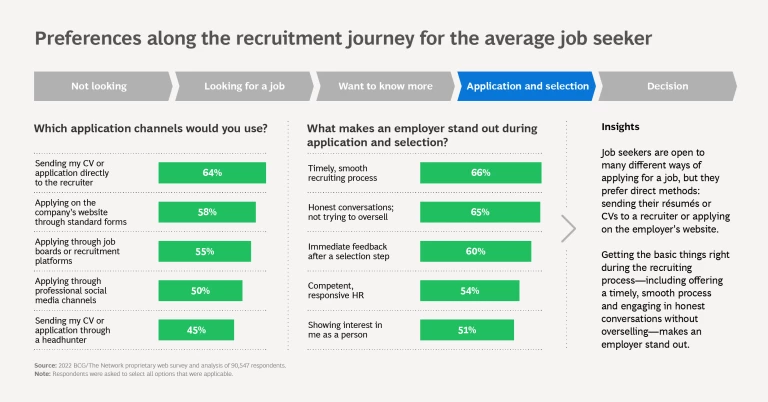

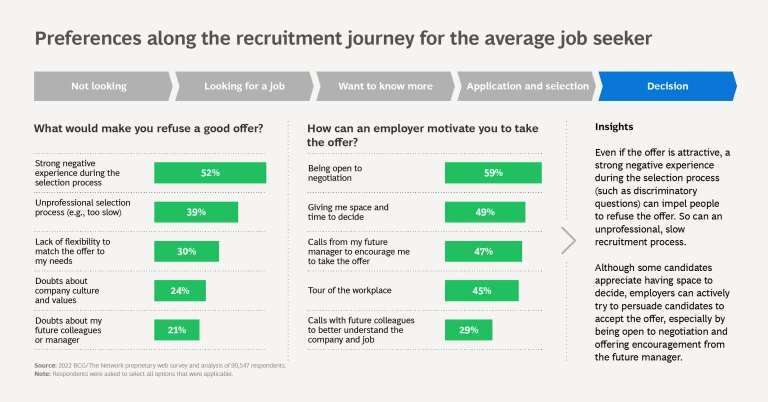

A bad recruitment experience can torpedo even an exceedingly attractive job offer. In our survey, 52% of respondents said that they would refuse an otherwise attractive offer if they had a strong negative experience during recruitment. It’s important for would-be employers to understand a candidate's ideal recruitment journey at each step of the way.

What Employers Can Do

In our experience, employers can take a number of effective steps to maximize their attractiveness to desirable job candidates. Here are six key actions to consider.

Segment your approach to appeal to different target personas. At the outset, employers must have a clear view of the specific skills and profiles they need—and this entails developing a structured, future-proof workforce-planning process. Then they must segment these requirements into personas with distinctive needs, differentiated employer value propositions, and customized recruitment journeys. It can be helpful to think of potential employees as customers, understanding the needs of different segments and adjusting the recruitment approach accordingly.

Our research proves that people’s priorities vary depending on their life situation, job role, motivations, labor market position, and more. By gathering data from various sources (social media, surveys of your new hires, focus groups), you can shape talent personas (such as senior professionals with high expectations or young digital experts) and then reimagine the recruitment journey to make it—and your ultimate job offers—optimally attractive.

Clear target segmentation also supports a refined sourcing strategy. To recruit tech experts, companies can monitor large digital firms for layoffs or relocation moves, for example; to bring in agile coaches, they can pay attention to the local startup scene.

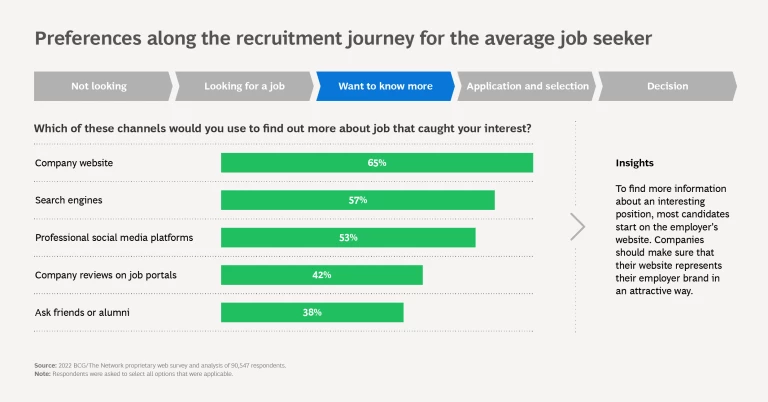

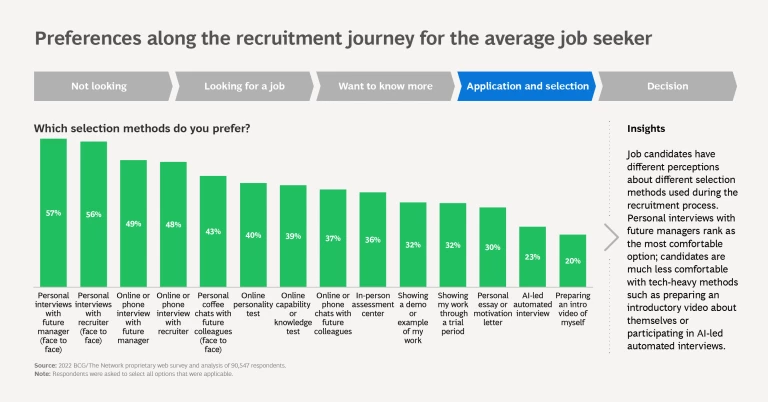

Reimagine recruitment as a personal journey. Our data shows that job candidates’ impressions during recruitment have a bigger influence on their decisions than employers may think. Nevertheless, many companies continue to manage recruitment as a corporate process, optimized for administrative requirements and legacy systems and not for creating a positive and persuasive experience for prospective employees. Best-practice employers apply a zero-based process design, stripping the process down to the essential steps and focusing on the value add for the candidate.

Job candidates’ impressions during recruitment have a bigger influence on their decisions than employers may think.

This type of candidate-centric design should identify moments of truth when trust can be built. Many of our survey respondents cited a desire for honesty about the role itself and the financial compensation that comes with it, along with continued contact (rather than being “ghosted”) and feedback on their progress along the recruitment journey. Other ways to create trust include a genuine conversation about the potential manager’s own experiences, a chat over coffee with future colleagues, and a walk on the shopfloor.

Recommendations from friends or acquaintances can be another key element in building trust; job seekers value these insights and referrals. Already, leading companies leverage employee referral programs, with great results.

Overcome your biases to increase your talent pool. The bigger the talent pool, the greater the likelihood of accessing needed talent. To broaden the pool, companies should look beyond the usual requirements for hiring. They may, for instance, put less emphasis on formal requirements for attributes such as degrees and years of experience and focus instead on skills, motivations, and potential. Employers may also consider hiring candidates who are a 70% fit and then training them to quickly come up to speed on the remaining requirements.

STARs—people who are “skilled through alternative routes”—can be a great source of talent. They lack a bachelor’s degree but have work experience and skills that ready them for higher-wage jobs. There are some 70 million STARs in the US alone. Indeed, many of our survey respondents said they wished employers would look at experience versus degrees and certificates.

Yet another possibility is to look internationally, to emerging talent markets, where candidates might be willing to sign on to work remotely—or even to relocate. To reach further groups of unexplored talent, companies can work with skilling and inclusion programs geared toward finding jobs for minorities and disadvantaged populations. Finally, diversifying their panel of interviewers can help employers hire a truly broad range of talent.

Another possibility is to look internationally, to emerging talent markets, where candidates might be willing to sign on to work remotely—or even to relocate.

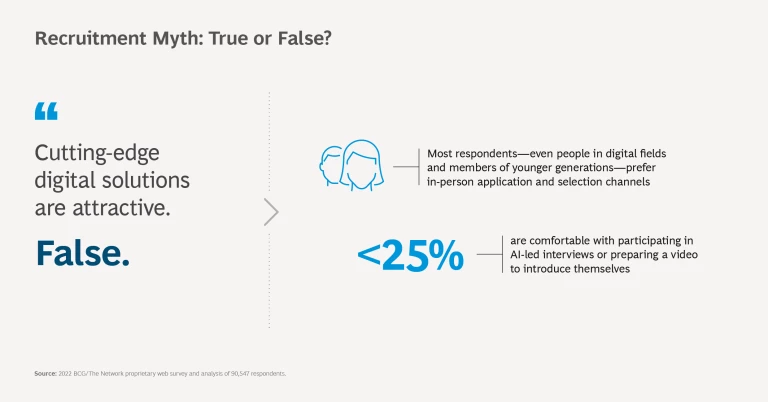

Wield digital tools impactfully—but selectively. Although the digital HR market is booming, our survey found that candidates do not want digital solutions to replace personal contact. Most people today wouldn’t be comfortable being interviewed by an AI entity in place of a human interviewer or talking to a chatbot about the recruitment process. This doesn’t mean that employers should stick to brick-and-mortar processes. Digital alternatives can work well for non-candidate-facing HR tasks (a strong applicant-tracking system, for instance, or AI-enhanced résumé screening). They can also work for certain candidate-facing tasks, such as automated interview updates or app-based preparation tips. There are also some situations where a gain in efficiency may justify a potential tradeoff in candidate satisfaction. In fact, digital tools can help deliver on some of the things that prospective employees want to see in the recruiting process, including prompt responses, clear communication, and well-defined timing.

Get culture fundamentals right. The prospect of a salary boost or higher seniority can attract candidates, but in the long run they want a good work-life balance and flexibility. Employers can usually meet these needs by offering hybrid working models (and even the option to work from anywhere, including different countries), flexible hours (part-time hours, for example, or options to adjust work shifts), and access to family support services. Offering these benefits is an excellent way to attract candidates. Make sure that they know about these options.

Of course, a good work-life balance is about more than working from home or choosing work shifts. It comes back to viewing the employee as a whole person, not just a worker, and it means formulating solutions that match individual needs. In many cases, this may require managers to significantly shift their mindset.

A good work-life balance comes back to viewing the employee as a whole person, not just a worker.

Re-recruit your internal talent. Often people decide to look for a new job in hopes of advancing their careers and improving their opportunities. If they could find those things with their current employer, they might reconsider leaving. In a hot talent market, retaining existing talent is critical. It’s therefore worthwhile for an employer to maximize its existing talent’s potential and even to look to former workers and freelancers.

Formal internal talent mobility programs can help match existing employees with project needs and job opportunities. When this arrangement enables organizations to respond quickly to market opportunities and enhances their workers’ career development, it’s a win-win.

Employers can’t afford to let recruiting missteps leave them without the talent they need—or, worse, damage their brand in a way that makes attracting talent even harder.

In the war for talent, talent may have the upper hand today, but a rapprochement, or reconciliation, is entirely possible for employers that approach candidates in honest, open-minded, and flexible ways.

Click below for closer looks at different kinds of job candidates:

| Digital talent People with jobs in IT or digitization, analytics, and automation | Passive talent People who are not actively looking for a job right now but are open to a good offer |

Highly experienced talent People with more than 20 years of work experience and a master’s or higher degree | Deskless workers People who must be physically present at their worksite (for example, in health, hospitality, retail, or manufacturing) |

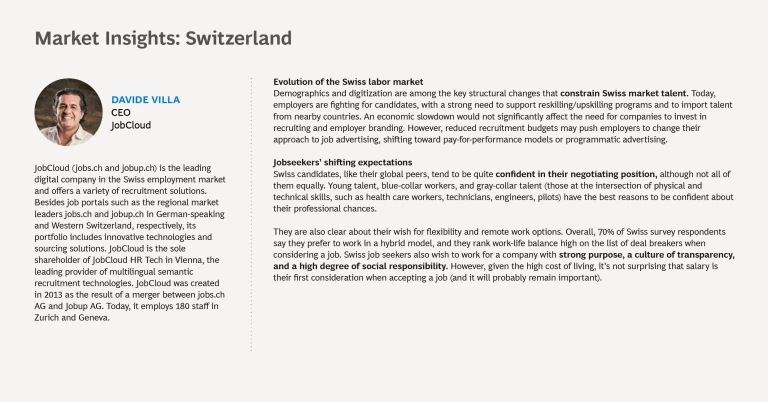

Explore the market insights below:

Acknowledgments

We are especially thankful to Davide Villa and Frederic Nguyen for their expertise and insights.

Additionally, we extend our thanks to our colleagues Valeria Rondo-Brovetto, Paulpiwat Na Songkhla, and Julie Bedard for their insights, research, coordination, and analysis.