It’s been called the “death of the degree.” A static college degree seems less relevant when rapid technological change requires employees to dynamically acquire new and evolving skills —to upskill and reskill, again and again. People looking for employment agree: in a 2022 BCG survey, many job seekers told us they wished employers would look at skills and experience instead of degrees and certificates.

And now, many companies say they are doing just that.

But how much, and how successfully? To better understand the prevalence and impact of skills-based hiring, Lightcast and BCG took a big data approach, examining more than 20 million job postings. (See “Methodology.”)

Methodology

Job-Posting Data

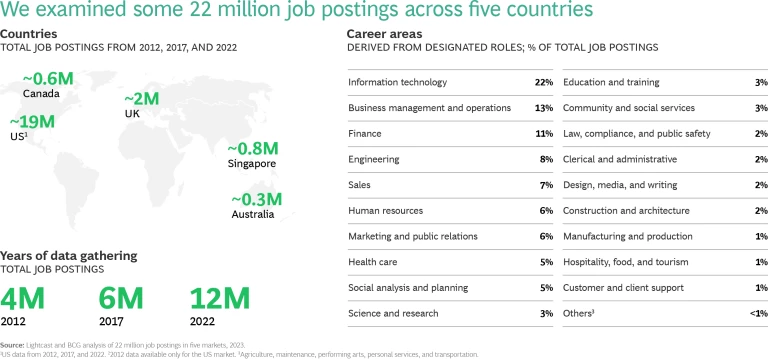

To conduct this analysis, Lightcast mined its dataset of millions of job postings. Lightcast collects postings from more than 65,000 online job sites, aggregating them, removing duplicates, and extracting data from the text to create a comprehensive, current portrait of labor market demand. This includes information on job titles, employers, industries, and regions, as well as required experience, education, and skill. The analysis is based on 22 million job ads across five countries in 2012, 2017, and 2022. We used machine learning to clean and standardize the data. See the exhibit below for more detail.

Lightcast identified occupations that normally require a bachelor’s degree or the equivalent based on job ad data, defined by at least 50% of job ads for the given occupation requiring a bachelor’s degree or higher. We then excluded occupations that require specialized education and licensing, where skills-based hiring is not feasible (doctors, lawyers, dentists, and so on). We based our analysis on five markets from different regions, representing a mix of cultures.

The following counts represent the number of occupations analyzed for each country:

- US: 265

- Canada: 242

- UK: 253

- Australia: 227

- Singapore: 170

Social Profile Data

Lightcast uses social profile data to understand the supply side of the economy. When people share their career history online, they offer insight into their education, skills, and career trajectory. By collecting aggregated, anonymous data from millions of profiles, Lightcast can measure the supply of talent in a region and provide insight into how skills and jobs develop into career pathways, enabling success and opportunity for workers. The dataset used contains profiles for more than 100 million anonymized individuals and contains information on job titles, companies, skills, and education. As with our analysis of job postings, we used machine-learning algorithms to deduplicate profiles and enrich the raw data contained in each profile—job titles and company names were standardized, skills were extracted, and education information was standardized.

Specifically:

- Lightcast analyzed 13 million US profiles to understand how skills-based hires differ from other hires in their career progression.

- First, this involved identifying skills-based hires: those who have worked in a role that usually require a bachelor’s degree or higher but do not possess a bachelor’s degree.

- We also identified traditional hires: those who are working in a role that generally requires a bachelor’s degree or higher and do possess a bachelor’s degree.

- Then, we looked at the role and company the person started at most recently, in the 2014-to-2017 period, and calculated tenure at that company in that role and in other roles, as well as promotions that they had at that company. We looked at jobs held through end of 2022.

- We divided the population into skills-based hires versus traditional hires to understand how career outcomes differ.

What’s Tearing Down the Paper Ceiling?

The answer lies in these trends:

- As noted, technology is driving a constant need for new skills, especially given the advent of AI and generative AI . But according to Pearson Business School research, only 13% of college graduates have the skills needed to start a job right away. Further, 54% of college graduates don’t work in their original field of study, and the jobs that will be available in five to ten years might not even exist today. For all of these reasons, the value of a traditional degree has come into question.

- At the same time, organizations are struggling to find the talent they need. Unemployment remains remarkably low, the workforce is aging, and open positions remain unfilled.

- Moreover, employees’ expectations have evolved . Workers are increasingly mobile. They seek flexibility. And they hold the power in a market where there’s greater competition for talent than ever before.

- Meanwhile, candidates who are self-taught or who gained their skills through experience are becoming a major force on the labor market: in the US alone, 70 million people can be categorized as “STARs”—workers without bachelor’s degrees who are “skilled through alternative routes.”

In the ensuing tug-of-war for skilled individuals, organizations must rethink their approach to recruitment. They must widen their recruitment lens to capture the diverse skills and experiences of a changing workforce. They need to shift from “degree and pedigree” to “will and skill.” By embracing skills-based hiring, they will tear down the paper ceiling that has kept individuals without degrees from entering certain occupations and advancing once there. As one CEO we interviewed told us, “A person’s educational credentials are not the only indicators of success, so we advanced our approach to hiring to focus on skills, experiences, and potential.”

Where Is Skills-Based Hiring Taking Hold?

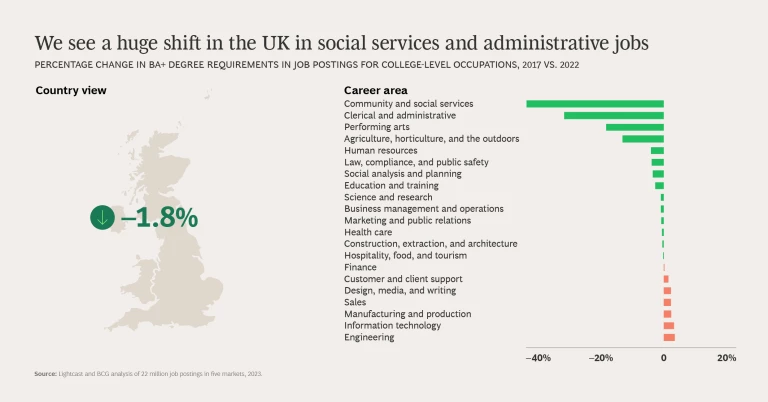

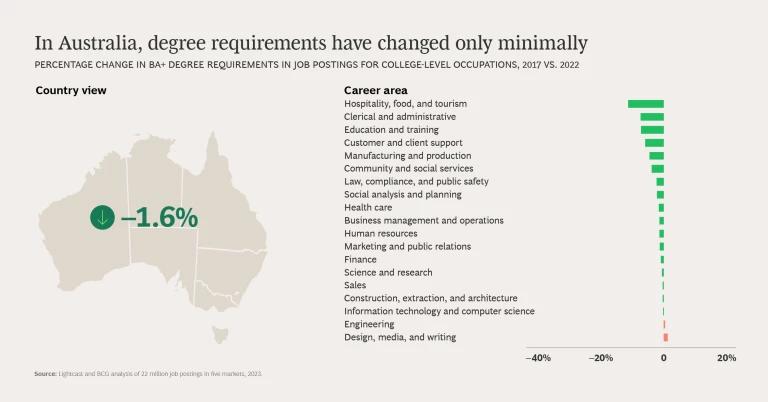

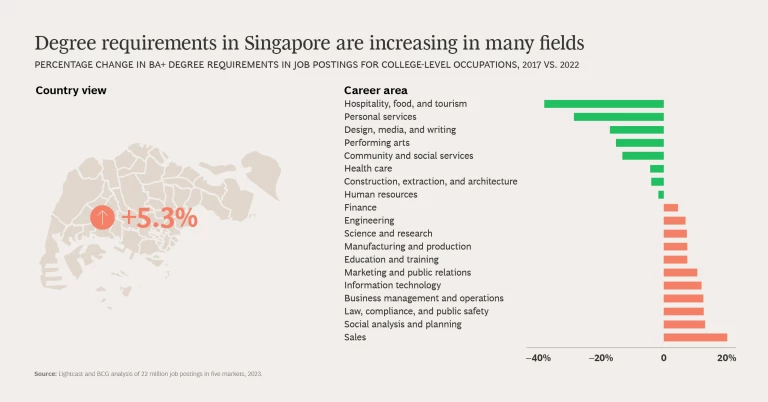

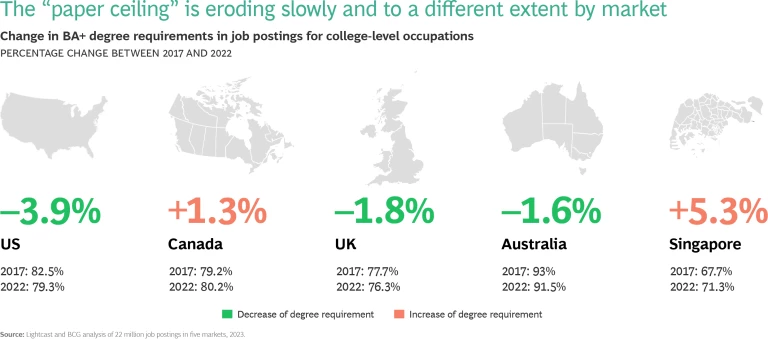

In many countries and professions, it seems that employers are beginning to embrace skills-based hiring. In our analysis, we looked at jobs that would historically require a college-level degree or equivalent (“college-level jobs”) and compared the percentage of job ads that actually asked for one in 2017 versus 2022. On average, we found a slow decrease in the share of job ads that require degrees. However, we found major differences driven by geography and occupations.

Trends by Country. When it comes to a decrease in degree requirements, the five countries we analyzed show very different trends. Labor market conditions don’t explain these differences—for instance, lower unemployment does not translate to a trend toward relaxing hiring requirements. Different starting levels for degree requirements could account for some of the difference, but not all. Cultural factors are likely at play: Do employers have an open mindset, for example? Do they see the value of a diverse workforce?

The US leads the shift to skills-based hiring, across career areas. Many large employers with a sizable US labor force are embracing the trend, among them Dell, Accenture, IBM, and Amazon. The US government is, too: In January 2021, the White House announced limits on the use of educational requirements when hiring for IT positions. Looking predominantly at college degrees, it said, “excludes capable candidates and undermines labor-market efficiencies. Degree-based hiring is especially likely to exclude qualified candidates for jobs related to emerging technologies.”

In Canada, the UK, Australia, and Singapore, there is a lesser shift and a different mix of career areas affected. In some areas, the requirement for a degree even increased from 2017 to 2022. This is particularly notable in Singapore, where the emphasis on degrees continues, even though the Singapore Institute of Management stated in March 2023 that “there are 2.5 vacancies for every unemployed person here in Singapore ... employers must look to widen the talent pool by going beyond the convention of looking at education qualifications.” Nonetheless, the Institute pointed out, one job advertisement seeking a driver of heavy vehicles included a requirement for a bachelor’s degree.

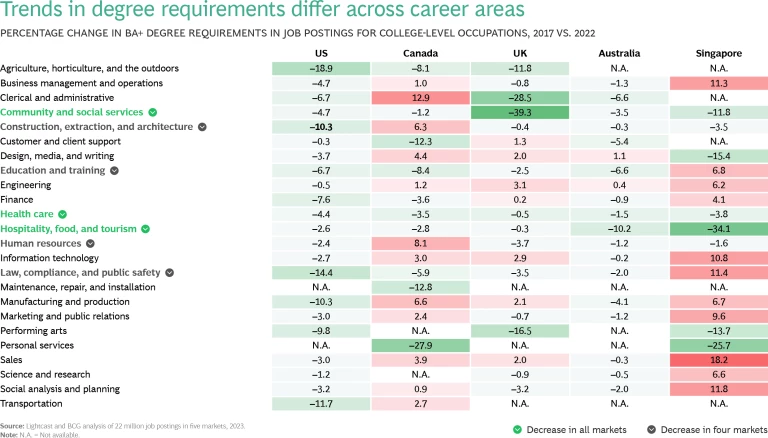

Trends by Career Area. Not surprisingly, the nature of a job has a significant impact on degree requirements. What is surprising? The large differences we see across markets even within a single career area, such as IT, business management, and marketing.

For some occupations, the need for degrees is decreasing across all five countries: in community and social services (for example, counselors and case workers), in health care (for example, support roles, such as lab technicians, hospital staff, and medical practice managers), and in hospitality, food, and tourism (for example, event planners and entertainment managers). Because the developed world faces major talent shortages in all three of these areas, it’s not surprising that employers are relaxing their expectations.

In several areas, degree requirements are also decreasing in at least in four of the five countries. Among them:

- Education and training roles—which do not necessarily mean teachers. The greatest shift is in support roles, such as college and university administrators, school directors, and instructional designers.

- College-level occupations in the construction, extraction, and architecture career area, such as architects, landscape designers, and construction managers; this is another area well known for labor shortages.

In several career areas, the picture is mixed. These include sales, marketing, manufacturing, and—interestingly, given the high demand for talent—IT. (See “Do IT Workers Need Degrees?”) Although the US shows a decreasing degree requirement in IT fields, other markets often think differently.

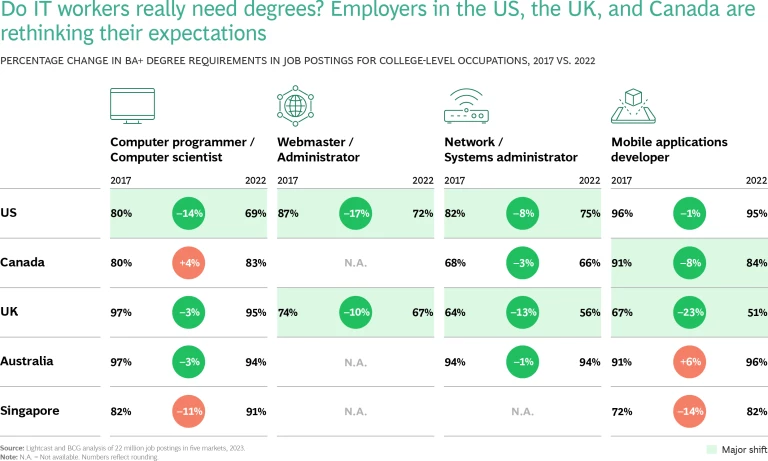

Do IT Workers Need Degrees?

Given the speed of digitalization and technological change, IT and digital talent remain a hot commodity, and demand outweighs supply. Meanwhile, with the democratization of education and the many online courses available, self-learning is becoming a completely legit way to pick up computer science and web development skills. Shouldn’t this prompt employers to be less picky about degrees?

Breaking down our data to focus on a select set of specific occupations, we see an unmistakable change: companies are rethinking their expectations when it comes to IT roles.

A few examples:

- In the UK, only 51% of job ads for mobile application developers listed a bachelor’s degree as a requirement in 2022, 23% lower than in 2017.

- In the US, only 69% of 2022 ads for computer programmer or computer scientist roles asked for a degree, down 14% from 2017.

Engineering is the only field where the paper ceiling remains in place: employers in four out of five countries have increased the demand for degrees in this field. This may have to do with safety concerns and regulations affecting such roles, as well as the highly specialized nature of engineering jobs; shorter courses and on-the-job learning may not easily replace complete degrees.

Is Hiring Based on Skills Worthwhile?

In a word, yes.

This is a message the American Psychological Association delivered decades ago and still stands behind. A hire that is based on skills, versus one that is based on education, is five times more likely to predict job performance.

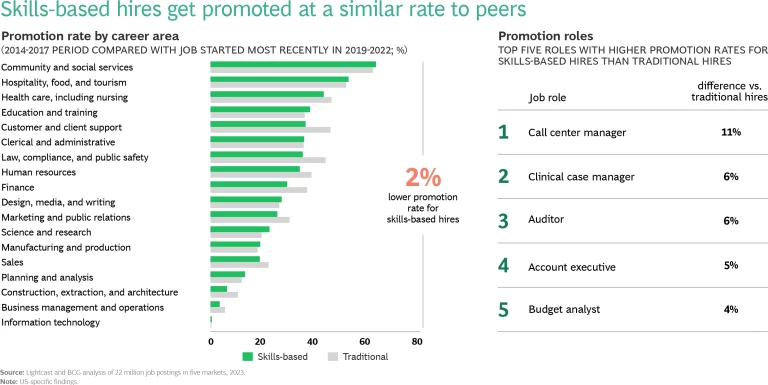

For our analysis, we looked at promotion rate and tenure at companies, using the US as an example. (The US is a pioneer in skills-based hiring, and data is widely available.)

Promotion Rate. Generally, those hired on the basis of skills get promoted at a rate comparable to that of traditional hires. They were only 2% less likely, on average, to be promoted in the same period as their traditionally hired peers.

It follows that in some career areas, employees seem to be promoted more slowly (law, business management, and customer support, for example) and in others, more quickly (social work and call centers). This suggests that skills-based hires perform on a level similar to that of their peers and perhaps need just a bit more time to merit their first promotions.

Our expert interviews support this finding. Several interviewees mentioned that skills-based hires work harder and are more motivated. “Hiring managers were surprised by the performance of skills-based hires who had no degree,” said a representative of a top US streaming company.

Apart from hard work, skills-based hires also bring with them specific experiences and abilities. During our interviews, presentation skills, problem-solving skills, and overall maturity were highlighted as differentiating factors.

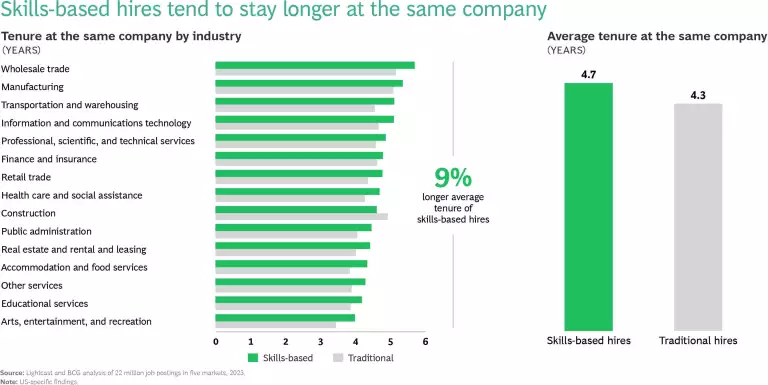

Tenure. We found that skills-based hires are more loyal to their employers. They have a 9% lengthier tenure at their organizations compared with traditional hires.

This trend is true across most industries and professions but is especially pronounced in trade, transportation, and food services as well as public administration, information and communication technology, and professional services.

Our expert interviews underscored the trend. “Skills-based hires have better problem-solving skills and in general are more interested in exploring the firm,” said an interviewee from a US-based multinational e-commerce company. And an expert from a US-based multinational tech company noted, “Skills-based hires demonstrate high engagement and motivation.”

How Can Organizations Succeed with Skills-Based Hiring?

We collected insights on what makes skills-based hiring successful. Here are five practical tips for employers seeking to widen their hiring lens.

Challenge the biases in your talent strategy. Be more open-minded. Is a degree really required for a specific job? Our data indicates that the paper ceiling is vanishing even in jobs that traditionally called for a degree. Tradition can be hard to overcome, of course. So employers must ask themselves, If this job seeker has the skills we need, does it matter how they acquired those skills? As an example, Goldman Sachs recently shifted to what it calls a ”skillset recruiting” approach. Through the company’s new online platform, candidates don’t apply for jobs—they apply to specific skill areas, then participate in skill testing and get referred for the most relevant jobs based on their skillsets.

Know the skills you need. Our research shows that skills-based job ads include a higher number of skills than traditional job ads. Traditional data-scientist job ads, for example, list approximately 28 needed skills, whereas skills-based ads for the same role will list as many as 37. Skills-based ads especially overindex on transferrable skills, such as collaboration and communication, which can be a foundation for success in any job. So employers hiring on the basis of skills must have a deep understanding of those skills and advertise for them. This involves being able to dynamically forecast skill needs as well as a deep understanding of current and future skill profiles.

Up your skill assessment game. The big risk when hiring based on skills rather than a degree, especially a degree from a tried-and-true institution, is the lack of “proxy proof” of candidates’ qualifications. Instead, employers have to obtain that proof by assessing and testing candidates’ skills, which they often aren’t prepared to do or don’t know how to do efficiently. They can look at other proxies: microcredentials (learning badges from short, often digital, courses), completion of online courses, recommendations, or the results of specific projects. They can also test candidates by asking them to demonstrate skills: writing code, participating in a trial period, or playing a game-based simulation that will test skills, for example. New tools leveraging GenAI are able to simulate real interactions to a high degree with little effort required on the employer’s end; they can be a useful way to efficiently assess thousands of candidates.

Support integration and an inclusive culture. Sometimes, the main barrier to skills-based hiring is cultural. Managers want to hire people who went to the same schools they did. Recruiters don’t want to take a risk on people from nontraditional backgrounds. Many company leaders followed traditional routes and expect their successors to do the same. In such an environment, skills-based hires may feel discriminated against or just not welcome.

Just as employers are increasingly conscious of their diversity, equity, and inclusion agenda with regard to gender, race, and more, they might also aim for diversity in employees' educational and career backgrounds. Some practices to consider would be ensuring that members of recruiting panels have diverse educational backgrounds, information regarding degrees from candidate CVs, training managers on avoiding unconscious bias, or even setting targets for alternatively skilled candidates.

Keep being skills-based—it’s not just about hiring. After they’ve brought skills-based hires onto their teams, employers should continue to support those employees’ career progression. Promotions should be based on skills, as should other internal moves and talent decisions. Several talent marketplace tools help to facilitate this. Novartis’s AI-powered internal talent marketplace uses information on employees’ skills and goals to predict, match, and offer roles and projects, for example.

However, a move like this requires a significant mindset shift in the organization—from ”talent hoarding” to ”talent sharing.” Managers as well as the HR function need to get comfortable with enabling skills-based, flexible career paths, and senior leaders have a major part to play as role models.

The insights and outlooks of employers and employees are converging.

One executive said: “We’re always looking for ways to bring broad and diverse perspectives into our workforce.” According to another: “It’s really important to us that we are drawing from all different backgrounds.”

And one job hunter seeking a role in education shared: “Sometimes experienced employees outwork and outshine a degree.” Said another: “I wish they would focus less on education and more on skills, experience, and examples of what you can do as a future employee.”

Given the need for more employees, given the need for evolving skills, and given the makeup of the potential workforce, the doors to less traditional hires are opening. Employers must welcome and nurture the applicants who have the skills and the will to step in and do the job.