As the world emerges from the pandemic, most governments are feeling strong pressure from today’s volatile economic environment. Countries are beginning to compete for capital investment and talent, even as they struggle to maintain growth. No matter what happens with inflation, innovation, and international geopolitics, there is one certainty: the need for national economic strategies will grow more urgent during the next few years.

As a policymaker, you may already have a plan to meet this challenge. You want to create a hub of innovation and enterprise, attract investment, and build jobs for your citizenry. However, you cannot build out every industry or run numerous economic reforms; you must set priorities. In short, you need a national economic value proposition (EVP) to guide your actions and investments and lay the groundwork for success.

In the private sector, a value proposition is a simple statement of how an organization will succeed: where and how it will invest and why those actions will work. This is not just a vision or mission statement. It articulates the company’s business ecosystem strategy : how it will create advantage for the organization and others. A value proposition identifies the company’s innate strengths—the capabilities that have achieved success. It lays out a path with leverage—making the most of investments. And it targets specific beneficiaries—the stakeholders who can become important allies. A focused value proposition makes a company attractive to all current and potential stakeholders: employees, customers, suppliers, and leaders of the communities in which its headquarters and major facilities are located.

Governments are finding similar power in their EVPs, especially in fostering economic development . In this context, a value proposition is a strategic articulation of the economy’s potential attractiveness to firms, capital, and labor. It expresses why businesses will relocate or start new enterprises there, why investors will fund those businesses, and why skilled, talented people will migrate there. Ultimately, the economic value proposition is the pathway to an energetic, prosperous nation, with a solid base of industries and jobs unique to that locale .

A value proposition for a geographic area articulates the economy’s potential attractiveness to firms, capital, and labor.

The Role of Government

Many government leaders have a clear idea about how their national economy should grow. But a strong vision alone is not enough. The vision must be brought to life—by discovering and articulating the distinct value that your particular economy can offer.

A number of countries have used economic value propositions as a starting point for economic growth. The design and development of EVPs follows a single focused process. This represents a deliberate change from past approaches to economic growth.

The process involves developing answers to three critical questions:

- What are our strengths as an economy? What value can we offer, now and in the near future?

- Where do we have leverage to act? What can our economy do to deliver the value we want to create? What tactics can we support and enable?

- Who are our target beneficiaries? Who will benefit most from this value proposition? And what role can they play in helping to move this forward?

This type of inquiry is valuable for an economy of any size, at a national or local level. To capture a full range of perspectives and ideas, assemble an EVP consortium to conduct this inquiry. This group can include business, labor, community, and government leaders—with common aspirations and a commitment to follow through.

To help you better understand the process for developing an EVP, let’s take a closer look at each key question.

What Are Our Strengths as an Economy?

To begin, unearth the value that the economy currently offers, as well as its potential as a base for future development. The most important strengths are unique key value characteristics that are difficult for others to copy because they are grounded in geographic advantages or embedded history. Some may be inherited, like ocean access or arable land. Others may be acquired, such as an innovation ecosystem or a tax system that attracts multinational corporations.

For example, Switzerland has benefited from its long history as a financial center. The country’s banking regulations have supported privacy for account holders since the 1930s, and its two largest cities, Geneva and Zurich, are both ranked as broad and deep global leaders by the Global Financial Centres Index. Canada has instituted similar rules designed to attract business, favoring start-ups and entrepreneurship.

At BCG, we have identified more than 50 indicators which can be a starting point to identify the strengths of your economy. Many of your value characteristics will be best expressed as economic indicators, including but not limited to the following:

- Corporate tax rates

- Average start-up costs

- Cost of living

- Level of investment in research and development

- Return on investment to shareholders in key businesses

- Wages for particular categories of talent

- Trade flows (both imports and exports)

- Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and other factors related to availability of capital

- Availability and cost of local financing

- General economic parity (the contrast between rich and poor)

- Employment

- Labor mobility and the inflow and outflow of people over time

In addition to economic factors, consider characteristics related to quality of life, work, and society—such as ease of doing business, proximity to emerging markets or commercial hubs, cultural diversity, and access to open space and recreation.

Typically, just a few value characteristics will stand out as truly distinctive for any country or city. For example, Switzerland has many attractive qualities as a place to live or do business, but only three are core to its position as a center of economic value. Ease of doing business in the country attracts many companies, particularly since it is so close to the European Union. The high level of banking privacy has made it a longstanding international hub for financial services. And Switzerland’s high talent level continues to attract innovative enterprises, especially in fields like pharmaceuticals.

Matching Strengths to an EVP Archetype

Once you identify a core set of strengths, assemble them into a profile—a written summary of the strengths you have or could easily develop, organized to show how they fit together. For example, you might say your country or region is strong in labor mobility and livability, and you are working on reducing the costs of doing business.

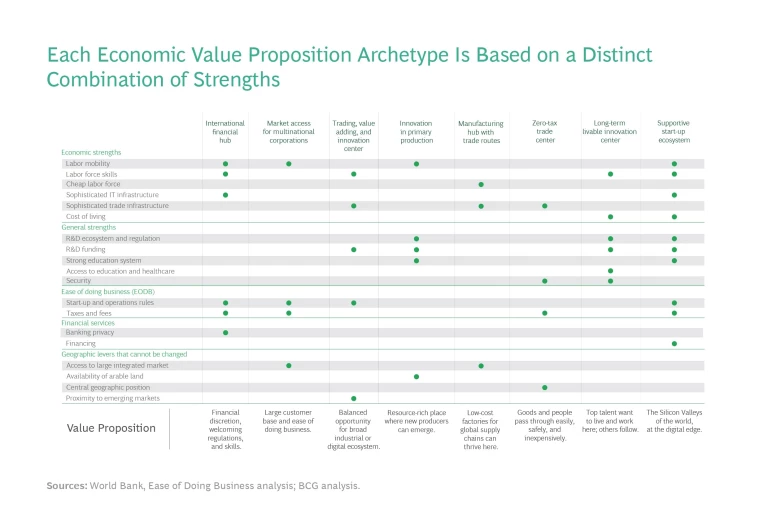

Next, review the profile against the eight archetypal EVPs: common models of value propositions that have succeeded in other places around the globe. Exhibit 1 summarizes these archetypes and the characteristics that define them. They each rely on distinctive strengths and favor different groups of beneficiaries. Each archetype also involves various investment priorities, tactical plans, and approaches to job creation and labor force development.

Consider the EVP archetypes as templates, which you can adapt and build upon to create an EVP that reflects your particular circumstances and goals. Because a value proposition reflects an area’s existing strengths and assets, an archetype that works well for one area would not necessarily be suitable for another area.

Define and refine your EVP using the value characteristics you have identified. For example, your country’s current or future strengths may include widespread broadband internet, a high level of banking privacy, and regulations that promote start-up formation. These would support creation of an international financial hub. Alternatively, if you are close to emerging markets—and could develop a highly skilled labor force and sophisticated trade infrastructure—this could support a center for trade and innovation. If you have many existing strengths and some resources for investment, you could choose a distinctive combination of several archetypes.

As you develop your EVP, consider how you will distinguish it from others. For example, your talent pool may be a core strength. Compare this aspect of your EVP to regional and global peers—those with similar population size, population density, and GDP. Do they offer potential employers knowledge and skills at the level that you can offer? Validate the comparison by looking at economic indicators and interviewing local stakeholders and international experts .

Each EVP archetype involves various investment priorities, tactical plans, and approaches to job creation and labor force development.

Where Do We Have Leverage to Act?

Having identified the strengths of your existing economy, now consider leverage actions you could take to expand and deploy them. If your EVP includes a technologically adept workforce, you might consider changing immigration regulations to encourage more highly skilled people to seek jobs in your country; supporting a more sophisticated IT infrastructure; funding research in related fields; and improving the education system across all levels. Other potential levers include streamlining regulations or investing in catalytic specialization areas to encourage focused economic growth.

Pick only two or three points of leverage. Your goal is to select a combination that you can invest in—both with money and a high degree of acumen—to complement your existing strengths.

Examples of Successful Leverage

Three examples of governments that have managed this type of leverage successfully are Ireland, Singapore, and the city of Melbourne, Australia. Ireland began to carve out its economic identity this way in 1987. A cross-sector group called the National Environmental and Social Council (NESC) released a comprehensive statement called a Strategy for Development. Ireland would offer a skill-based economy to multinational corporations, along with frictionless access to the European Union, the largest integrated market in the world. As the NESC report put it, Ireland would thus “develop a stable, sustainable, and competitive economy suited to a reformed Eurozone and globalized international system.”

To deliver on this value proposition, Ireland developed several forms of leverage, each complementing existing strengths. It invested in building workforce skills, encouraged labor mobility, set up tax incentives, and invested in information and communications technology (ICT) infrastructure.

Singapore began developing an explicit strategy for economic renewal in 2010, recognizing the changing geopolitical realities of the Asia-Pacific region. Working through committees composed of government, business, and labor leaders, the government released its latest economic value proposition in 2017, titled Pioneers of the Next Generation.

This aspirational value proposition is grounded in Singapore’s strengths. The country has a longstanding role as a center of trade and innovation, with proximity to emerging markets, laws, and customs that make it easy to start a business, and a well-developed trade infrastructure. To further its strategy, Singapore began to invest more in funding for research and development, and to cultivate an even more highly skilled labor force—providing training for local citizens and opportunities for qualified expatriates.

The logic of an economic value proposition can also apply to local governments. In Australia, the city of Melbourne has long been a center for agricultural and pharmaceutical innovation, supported by a leading research institution, the University of Melbourne. This led the local government to develop an EVP as a long-term livable innovation center. To bolster its ability to deliver, Melbourne’s government strengthened ties with nearby emerging economies in the Asia Pacific region, which represent an ongoing market for both agricultural and life sciences innovation. It has also developed the kind of urban environment—with good public transportation, support for cultural offerings, and improved access to education, healthcare, and open space—that will continue to attract skilled researchers and innovators from around the world.

Subscribe to our Public Sector E-Alert.

Who Are Our Target Beneficiaries?

Economic growth is generally a boon to business, investors, and labor—and key figures from these groups can become important advocates and allies for the new approach proposed by an EVP. Other potential beneficiaries include community groups and people living nearby; even if they are not directly involved in the value proposition, increased quality of life will tend to make a difference for them.

Therefore, it’s important to spend time considering target beneficiaries of the EVP. Who will gain the most when this value proposition is realized? How will they benefit? Most importantly, what role can they play in helping to move the initiative forward?

Through policies and practices, governments create an overarching approach to beneficiaries. The four basic approaches include:

- An economy open to all. This economy does not target specific businesses or individuals and may have a variety of strengths—combining activities all along the value chain, from primary resources to consumer marketing and distribution. There is generally a large proportion of skilled workers, either local in origin or expatriate. It is typically supported by multiple universities and large amounts of investment capital.

- A knowledge-led economy. This economy favors high-tech companies and those with intellectual property. It tends to be friendly to entrepreneurs and may cultivate an active investment base. Local universities participate in research and, ideally, provide training for local and long-term residents.

- An economy with open clusters. This economy favors particular domains or industries, as Melbourne does with life sciences and Switzerland with banking. It tends to have a highly skilled workforce in those domains, attracting expatriates from around the world.

- An economy with a closed labor market. This economy is generally protective of existing jobs and wary of cross-border connections. It will typically favor local businesses with a select group of foreign firms and expatriates. The government tends to prefer fostering blue-collar skills rather than technological skills.

Your choice of an economic approach will influence many specific decisions related to the EVP. It affects the labor force, support for education, and trade policies. Investors may also be affected, especially when policies favor local over foreign funds.

The countries and cities we studied all explicitly identified beneficiaries who might be called upon as allies to help support the EVP. For example, Ireland offers its value to multinational companies in the ICT and internet sectors, and to its labor leadership through related workforce development and expanded opportunities. Singapore favors multinational technology companies with a strong innovation focus, and Melbourne’s government sought to create ties with large pharmaceutical, digital technology, and mining companies.

Canada has begun to focus on global talent mobility . It has chosen skilled immigrants among its beneficiaries, and has been recognized for its marketing campaigns encouraging knowledge-workers to relocate. For example, the province of Nova Scotia invested 2.5 million Canadian dollars (CAD) in its campaign to attract skilled immigrants from within Canada and abroad to address labor shortages in healthcare and ICT. Alberta, another Canadian province, launched a CAD 2.6 million campaign called “Alberta is Calling” to attract skilled workers. It outlines advantages such as low cost of living, short commute times, career opportunities in emerging industries, and access to nature—with the goal of attracting workers into growing sectors such as technology, renewable energy, aviation, and film and television .

The most successful economies in the 2020s will have clearly defined value propositions that reflect their own distinctive identity.

Becoming Aware of Value

When government leaders gain experience with their economic value proposition, the way they manage the economy shifts. They temper efforts to control corporations within their borders by recognizing that economic competitiveness requires innovation—and thus a relatively light touch in business regulation. As designers and developers of EVPs, they recognize that individual skills and business capabilities are mutually reinforcing qualities. The stronger each becomes, the more they strengthen one another. This understanding may drive support for general education and training.

The most successful economies in the 2020s will be those that put this economic flywheel into motion. They will have clearly defined, developed, and articulated value propositions that reflect their own distinctive identity. The leaders of these economies will talk more openly about their strengths and challenges. “Let’s be honest,” you might hear an EVP consortium leader say. “Do we really have all the companies and research centers we need to develop ourselves as a biotech hub?” If the answer is no, this might lead the group to fill gaps they have identified or to consider switching to a different EVP archetype.

In these times of crisis and economic uncertainty , having a focused economic value proposition will be critically important. Defining a coherent EVP will become a rite of passage for many governments—a signal that they are ready to bring a new level of maturity to their economy.