One of the most powerful tools in promoting public health doesn’t come from a test tube, a vial, or a syringe. It’s data—and states are having a tough time extracting its full potential.

Data helps public health departments understand disease trends, plan strategies, and provide residents with a window onto a crisis, so they can become their own best advocates for staying safe. But the pandemic exposed—and expanded—cracks in the foundation. Outdated technology, hard-to-access (and often poor-quality) data, roadblocks in sharing key information: these factors combined to hinder a nimble and precise response.

The solution? A modern data system that fuels—and accelerates—decision making as emergencies evolve. This requires transformation: not filling in the cracks but building a new underlying capability for working with health-related data.

States need a modern data system that fuels—and accelerates—decision making as emergencies evolve.

Transformations take time, but with the right approach, they can start delivering value quickly. In a matter of months, states can see dramatic improvements in how they use data to care for their residents. By steadily building out their capabilities, health departments can keep getting better at capturing and leveraging data—and put us all in better position to meet the next emergency.

Outmoded Systems—and the Obstacles They Create

The challenges posed by outmoded data systems became apparent early in the COVID-19 crisis. To respond to the pandemic effectively, health departments needed the ability to capture an array of relevant information, including case counts and hospitalizations at a local level and statewide. At the same time, states needed to report timely and accurate information to the Centers for Disease Control so the CDC could shape and support a national response. But there were obstacles.

First, public-health data tended to be siloed: different providers, agencies, and community organizations collected and stored it independently of each other. Second, antiquated or incompatible infrastructure often made it hard to share this data. Finally, there was the data quality and consistency problem: different health providers often collected different types of data, or they labeled the same type in different ways.

To put it simply, if data paints a picture, health departments weren’t getting a Rembrandt but a police sketch. This hampered their ability to respond in optimal ways and at optimal speed.

If data paints a picture, health departments haven’t been getting a Rembrandt—they’ve been getting a police sketch.

Having recognized the problem, many states have started to implement changes. But these are typically patchwork solutions: ad hoc interventions that seal cracks without addressing the reasons those cracks exist. Preparing for the next pandemic requires a different kind of approach. At the core of the solution is a more flexible data platform—one that makes it easier to capture timely and high-quality health data, develop actionable insights, and make critical decisions on how to allocate limited resources so they can be deployed more precisely, in real time, as situations evolve.

How to build such a platform? The traditional approach to transformation would call for a top-to-bottom redesign, which generally takes three to five years to implement. That’s less than ideal. By the time states complete their redesigns, technologies and priorities are likely to have changed. More significantly, such an approach would mean that health departments—and the residents they serve—must wait years before they can reap the benefits of a more modern data system.

But what if you shaped the transformation so that you can start realizing benefits in the near term? If you could deliver value without the years-long wait? And build your new system in a flexible way, so as circumstances change, you can adjust your path forward?

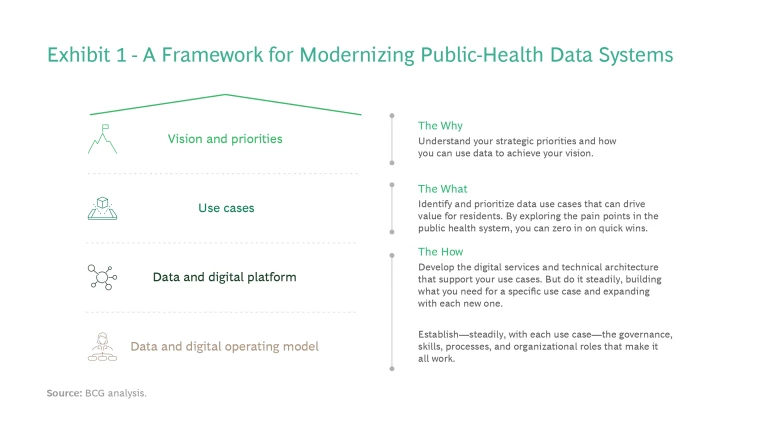

That’s the aim of a new approach to modernizing public-health data systems. (See Exhibit 1.)

It’s a framework built on four pillars:

Setting Your Vision and Priorities. The role of a public-health department—both its mission and how it interacts with residents, health providers, community organizations, and other stakeholders—will vary from state to state. Some jurisdictions take an expansive view of public health: everyone should have access to a broad array of health services. Others may define a health department’s role more narrowly; say, to ensure access to essential services. No matter the vision, it’s important to articulate it up front. Once you define your mission and your priorities, you can map out how data can help you achieve your goals—creating, in effect, your North Star for data modernization.

Identifying and Prioritizing Use Cases. By building your data system in a modular way, you not only deliver value quickly, but you can prioritize your most pressing health needs. Data use cases—whether they alleviate pain points in the public-health system, provide operational efficiencies, or create value in another way—enable this approach. Instead of trying to do everything at once (the traditional route), you break down your vision and goals into a series of smaller efforts. The idea is to identify discrete use cases and rank them by assessing their impact and feasibility. The use cases at the top of your list are the ones to implement first.

By focusing on high-priority use cases, you can deliver value—often very visibly—early in the journey. These quick wins also help generate buy-in—and funding—for the longer-term transformation.

Subscribe to our Digital, Technology, and Data E-Alert.

While the list will look different from one state to another, three use cases serve as a good starting point in fostering nimble and effective public-health responses:

- A 360-Degree View of Residents. By integrating a wide range of relevant but often far-flung data (including electronic health records, socioeconomic data, and screenings performed by other public agencies), health departments gain a richer, more holistic view of those they serve. They can see all relevant factors at once, optimizing decision making—and interventions—on both an individual and population-wide scale.

- Real-Time View of Public Health Indicators. With ready access to timely, high-quality data, health officials can more effectively tackle emerging, and often rapidly shifting, crises. For example, instead of basing a vaccine distribution plan on months-old case counts, officials can factor in current trends when shaping their strategy.

- Timely Data Sharing with the Public. An individual’s best advocate for health and safety is often themself. By sharing accurate, up-to-date data, health departments activate the public, enabling—and empowering—individual decision making. Data transparency is especially crucial in evolving emergencies, so savvy health departments will ensure that the information they provide is easy to visualize and interpret.

Steadily Developing Your Data and Digital Platform. Use cases don’t operate in a vacuum: they require the appropriate digital services and IT architecture. But this doesn’t mean you need to overhaul your entire technical infrastructure in one fell swoop. Instead, build what you need to implement a specific application. As you implement more use cases, you steadily build your capabilities—and build toward your North Star . So instead of waiting three to five years to flip the switch, you’re deploying your most critical capabilities quickly, often within two to six months.

Central to this approach is a data and digital platform (DDP). In the DDP model, you decouple data from your legacy technology, creating a separate data layer which systems can access. This lets you develop your digital services and IT architecture in a modular way. It also gives you flexibility. As you add—and start to leverage—new capabilities, you can adjust your path forward to account for changing priorities, technologies, and so on. You’re able to fine-tune your journey, adding and reprioritizing use cases as circumstances warrant and building out your DDP accordingly.

Creating—and Continually Refining—a Data and Digital Operating Model. To seize the full potential of a modern data system, health departments need to take a page from the digital-native playbook and combine technology with the right processes, skills, and ways of working. This means developing a new operating model for working with data: the organizational structure, governance, talent, and processes that enable the public-health outcomes the agency prioritizes. Governance is an especially important component given the sensitivities around handling and protecting personally identifiable information and personal health data.

What’s the best way to do this? Like your IT architecture, the operating model is something you develop steadily, creating what you need to implement specific data applications. As you add new use cases, you continually build and improve your model.

For both the technology and the operating model, it’s important to know your starting point. By assessing your current state, you’ll get a picture of what you have and what you need—helping you create a blueprint for delivering digital solutions securely, sustainably, and at scale.

Five Guiding Principles

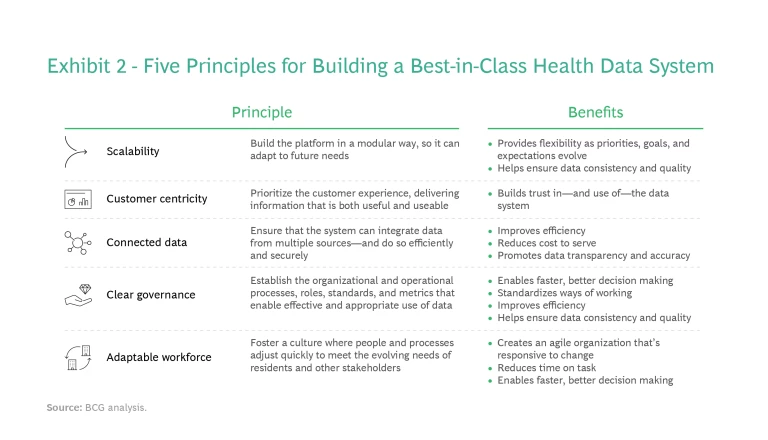

This framework has been battle-tested by many private-sector entities and their experiences provide valuable insights. Crucially, organizations that build best-of-breed data systems embrace five key principles (see Exhibit 2):

- Scalability. Build the data platform in a modular way that lets you deliver key outcomes quickly—and adjust your path forward as needs and circumstances change. Anchoring your effort on use cases and creating a separate data layer (via a DDP) makes it easy to scale as expectations evolve.

- Customer Centricity. View data use cases—and how you implement them—through a customer lens, where the customer is the individual, the health care provider, the agency employee, and every other stakeholder in promoting public health. By prioritizing the customer experience, you can deliver information that’s both useful and usable.

- Connected Data. Build your system so that it can integrate data from multiple sources and platforms. This not only improves efficiency (reducing manual effort), but it also enables health officials to see—and share—a richer picture of emerging situations and trends.

- Clear Governance. Establish and clearly articulate the processes, roles, standards, and metrics that ensure effective and appropriate data usage.

- Adaptable Workforce. Adopt agile ways of working and foster a culture—and mindset—that embraces change. The goal is to embed adaptability in the organizational DNA, so people and processes can adjust quickly to evolving needs and expectations.

Not all the momentum has been within the private sector. We utilized the framework to help a health ministry set up a data and intelligence unit to improve its ability to understand the pandemic’s trajectory and manage key health resources as the crisis unfolded. Familiar factors—complex and manual processes, duplication of efforts, inconsistent data and projections of likely future infection rates and resource demand—hindered visibility during the crisis and made it hard to coordinate resources across the health system.

Partnering with the ministry, we designed and automated processes to create a daily view of all relevant pandemic information and public-health resources (from hospital and ICU beds to staff and critical supplies). And we developed an operating model (including key roles and processes) to make it work. By enhancing data transparency, the ministry fostered faster, more precise decision making and based its planning and coordination on a deeper, more timely risk analysis of COVID-19’s spread.

Now Is the Time to Get Started

The pandemic spotlighted states’ urgent need to transform the way they use data to address public-health emergencies. Newly allocated resources can help make this happen. Federal funding is growing—with sources that include the American Rescue Plan Act, the CDC’s Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity for Prevention and Control of Emerging Infectious Diseases Cooperative Agreement, and the CDC’s Data Modernization Initiative.

Now is the ideal time to begin the data-modernization journey. Or at least to get into position—by setting the vision, identifying use cases, and assessing capabilities—for when additional funding sources become available. By better integrating, sharing, and using data, states can better tackle emergencies. And they can let the COVID-19 health-data crisis be the last.

The authors are grateful to their BCG colleagues Jacob Goren and Rebecca Milian for their assistance with this article.