Financial institutions understand the need to accelerate progress toward net zero —and many are actively advancing efforts to do so. But climate is just one part of a larger nature-based ecosystem on which people, industries, and entire economies depend. Today, many elements that make up that ecosystem, from water and critical minerals to farmland and pollinators, are under threat. Some are being depleted, others contaminated, and still others destabilized by habitat declines.

In their role as capital providers and advisors to entities and individuals around the world, financial institutions are at the epicenter of many of these changes, and their portfolios fundamentally depend on and impact nature. This two-way relationship gives institutions a unique vantage point to identify key risks, fund smart interventions and open new avenues of growth. By leading on nature, financial institutions can also facilitate a just transition that addresses environmental challenges in ways that support human rights, social inclusion, and the eradication of poverty.

Achieving these goals can’t be left to chance. For the sake of the planet and their own long-term growth, financial institutions need to develop a comprehensive nature strategy.

The Planet Depends on Nature—and So Do Financial Institutions

Over $40 trillion in economic value annually, or roughly 50% of global gross domestic product, directly depends on nature and its services. But the planet’s habitability has limits, and human activity is now stretching many of them to the breaking point.

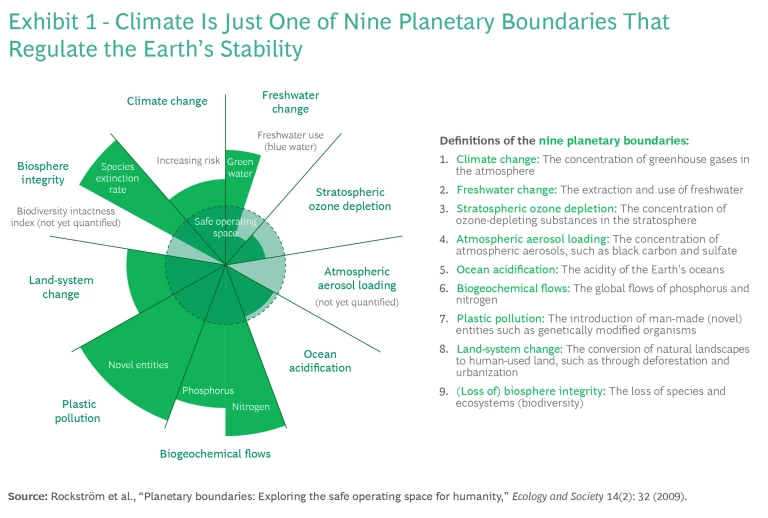

In 2009, a group of scientists identified a set of “ planetary boundaries ” –– a framework describing a set of environmental change processes that regulate the stability and resilience of the Earth’s system. Climate change gets the most attention, but there are eight others. (See Exhibit 1.) All have complex, interconnected feedback loops.

Scientists have determined that we have already breached the limits of six planetary boundaries, and others are at risk. The concern is that continued degeneration could trigger irreversible environmental changes. Despite these very real risks, however, there is some good news. The reversal of the Antarctic ozone hole, which was breached as a result of increased concentrations of anthropogenic ozone-depleting chemical substances, is a great example of the impact of decisive action. Thanks to international action taken as a result of the Montreal Protocol, the ozone layer appears to be heading toward staying within the planetary boundary threshold.

This is why it is so important for organizations, and financial institutions in particular, to demonstrate leadership in mitigating nature-related risks. Concurrently, they may also tap into the many value creation opportunities that exist.

Institutions face heightened exposure to nature-related threats in their corporate and investment portfolios. Those with a heavy concentration of investment in key industries such as agriculture or forestry, for example, may need to begin pricing in the risk of lower crop yields, weighing the potential for species loss, and calculating the resulting financial impacts. An analysis by the European Central Bank (ECB), for example, found that 75% of bank loans to companies operating in the euro area went to companies that had at least one major nature-related dependency.

Pressure from regulators is mounting, too. The Network for Greening the Financial System, consisting of more than 100 central banks, flagged nature as having significant macroeconomic and financial implications and recommends that institutions stress-test for biodiversity-related financial risks. In Europe, the ECB has begun to set supervisory expectations on risks stemming from biodiversity loss, water stress, pollution, and other environmental factors. And the EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive has created mandatory disclosure requirements on key nature dimensions.

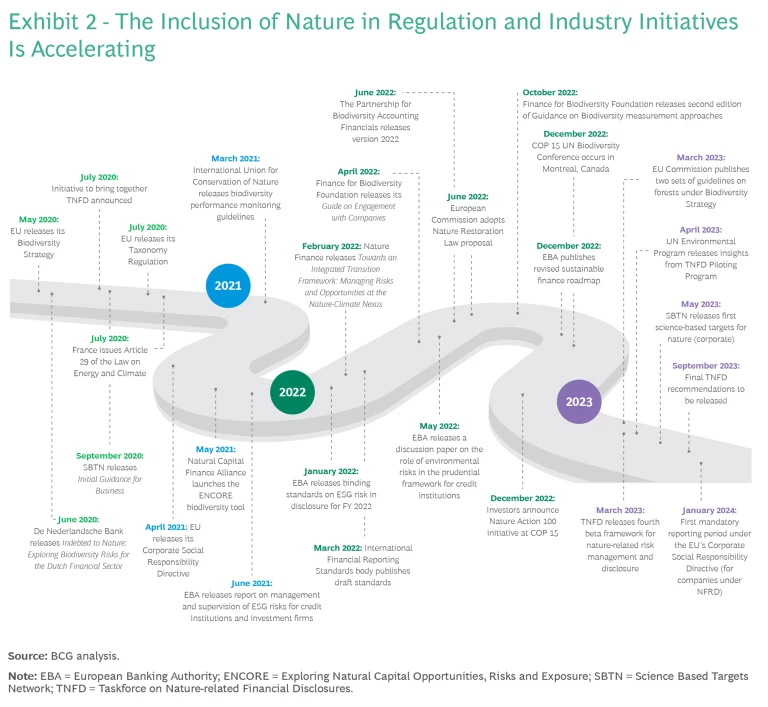

Globally, the market consensus is that nature-related disclosures will become mandatory for financial institutions much more quickly than was the case with climate-related disclosures. Regulatory momentum has been increasing. (See Exhibit 2.) And the insurance sector, an early barometer for risk assessment, is already preparing to factor nature-related risks into its underwriting and investing activities. In 2021, roughly three-quarters of the 108 insurance sector participants from 32 countries surveyed by the Sustainable Insurance Forum considered these risks to be financially material.

Crucially, a nature strategy can do more than mitigate risks. Nature-based solutions (NbS)—actions taken to protect, manage, and restore natural and modified ecosystems—are a burgeoning area with significant pent-up demand. The World Economic Forum reports that NbS and other nature-positive policies could generate more than $10 trillion in new business value annually. Yet few financial institutions have opportunities like these on their radar, leaving significant value at stake. Funding for NbS amounts to only $154 billion per year, less than a third of the total that the UN Environmental Program says is necessary by 2030 to stop biodiversity loss and land degradation.

Financial institutions also have an immediate and practical reason to start building a nature strategy, which is to ensure that their net zero plans don’t

inadvertently

create harmful impacts. Investments in renewable energy infrastructure, for example, can lower the carbon emissions of their portfolios. But they also create a tension with nature, since infrastructure consumes land and impacts biodiversity. Integrating nature strategy with net zero planning can help financial institutions approach target setting and investment prioritization in a way that reduces negative nature impacts and creates opportunities for climate mitigation. For instance, studies show that over one-third of the interventions to limit the increase in global temperatures to 2°C or less will come from NbS.

Nature Planning Is a New Concept, and Its Pillars Are Evolving

Although interest in setting a broader nature-based strategy is growing, approaches remain in development. The “Global Goal for Nature” set by the Science Based Targets Network (SBTN) defines a nature-positive world as one with zero net loss of nature since 2020, a net-positive state of nature by 2030, and full recovery by 2050. But nature is multidimensional. And interpretations of how to apply SBTN’s definition vary. In the absence of standards, financial institutions must determine what “nature-positive” means for their business and stakeholders—and be transparent in articulating that position.

Gaps in data and modeling are another challenge. Financial institutions need to measure impacts and dependencies across sectors and along client supply chains. But gaining a single source of truth on metrics and sources in order to map nature impacts and dependencies is difficult, given how critical location-specific data is. For example, water use in an arid region poses very different risks to businesses and the wider community than water use in areas with high precipitation. Another challenge to in-depth analysis involves the absence of comprehensive scenarios that would help financial institutions predict the impact of future nature developments on businesses. To discern potential vulnerabilities in near-term and longer-term supplies, financial institutions need insight into the specific locations of where their clients’ suppliers are based, but they also need the ability to forecast disruptions to those supply chains in order to identify potential hotspots.

Meanwhile, measurement methodologies to assess impacts and dependencies are maturing. Launched in 2019, the Partnership for Biodiversity Accounting Financials offers financial institutions a standardized way to account for biodiversity impact, much like the work of the Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials—but a comprehensive standard that addresses all nature dimensions will take time to crystalize. And although the SBTN has created a science-based target-setting framework for corporations, that framework hasn’t yet been adapted for financial institutions.

These growing pains are important to recognize, but they should not prevent financial institutions from developing a nature strategy. In fact, advantage will go to those that start now.

The Four Steps to Building a Nature Strategy

We have devised a simple, pragmatic, four-step framework to help institutions begin reaping the benefits of nature planning. The practices developed at each step are designed to flex and grow as the field of nature management matures, ensuring that time and investment spent today will pay continual returns.

Identify sectors with high nature exposure. As we’ve seen, nature-related exposures can trigger financial risks. Determining where these exposures sit in an institution’s portfolio requires holistic analysis of impacts and dependencies. (See Exhibit 3.) For instance, at first blush, health care companies might seem to have a lower overall environmental impact than other sectors. But closer examination reveals that they have high rates of water use, water pollution, and solid waste generation. Understanding where exposures are concentrated in a sector’s value chain is also crucial. For example, in food and agriculture, most impacts come from land use and direct exploitation, both of which are in the upstream supply chain. But in the chemicals industry, many come from pollution, which is located downstream.

In performing this analysis, rather than attempting to optimize every sector or activity, financial institutions should first focus on those that involve the greatest financing exposure. Off-the-shelf tools such as ENCORE, developed by the Natural Capital Finance Alliance, can help institutions begin to model nature-related impacts and dependencies by sector and geography. Institutions can then use in-house data to augment and refine their analyses. And while initial modeling is often qualitative, the insights gained from performing it can help establish priorities for the next phase.

Measure your nature footprint. Next, institutions need to transform qualitative insights into quantitative measures of impacts and dependencies. Doing so entails aligning on a set of metrics and selecting appropriate databases—steps that can quickly become extremely complicated, given the lack of standardization in the nature field. There are more than 300 biodiversity metrics and multiple measurement methodologies. For practical purposes, it can be useful to take a bottom-up approach, selecting metrics that consider direct drivers of nature loss such as land and water use and their impact on planetary boundaries. Working with impact drivers can help financial institutions identify which pressures are relevant to a particular business or geography, so that they can hold more meaningful discussions with clients. Alternative metrics such as mean species abundance focus directly on the state of biodiversity. Although they are helpful to consider, these broader measures are harder to link to specific client actions.

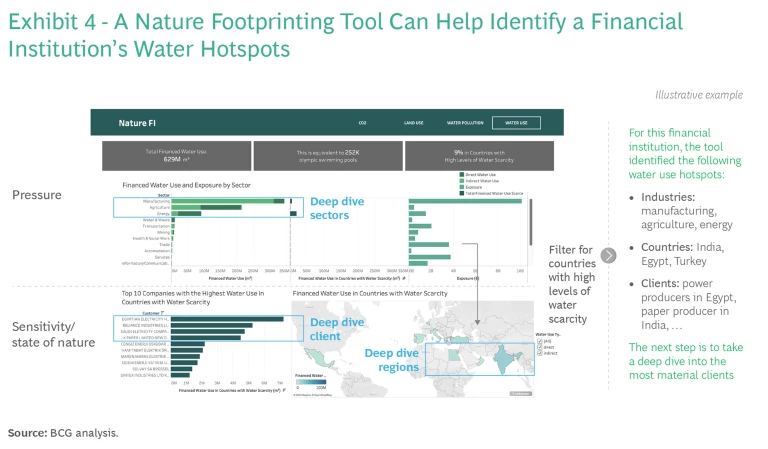

To gather information for the quantitative analysis, financial institutions can access company-reported data from third-party data providers. They can also use modeling databases such as Exiobase to estimate resource use by industry and geography. Other tools to help financial institutions quantify nature pressures across sectors and geographies are starting to emerge. (See Exhibit 4.) In addition, biodiversity footprinting tools such as Corporate Biodiversity Footprint and Global Impact Database can enable financial institutions to model different value chain elements. Still, no single solution currently supports a full value-chain assessment across nature pressures and scopes.

Over time, financial institutions can augment this data, creating their own modeling instruments and acquiring data from partner organizations and proprietary sources, to build a more accurate and granular picture. Lloyds, for instance, has begun gathering data on soil health, water quality, biodiversity, and carbon emissions through its partnership with the UK-based Soil Association.

Determine avenues for value creation. Having assessed potential impacts and dependencies on their portfolios, institutions can focus their nature strategy on optimizing them. This effort has two aspects: risk assessment and mitigation, and opportunity identification.

Much like climate risks, nature-related risks drive traditional risk categories—with credit risk being the most pressing category to consider, particularly for lending portfolios. From a portfolio perspective, financial institutions are starting to map sectors that carry high physical and transition risks in order to begin monitoring and managing overall exposure. They can analyze physical and transition risk drivers, such as water stress and deforestation policies, under basic scenarios to assesses the financial impacts on portfolio companies. Significant gaps in defining comprehensive nature scenarios and in quantitatively modeling the probability of default across the portfolio persist. But institutions are making positive first steps to integrate qualitative factors in credit risk assessment. As institutions prioritize credit risk assessments, this is a very valuable starting point.

On a company level, financial institutions can use qualitative or quantitative scorecards and adjust their due diligence processes to begin steering the credit process. They can then translate risks at the counterparty level, adjusting a client’s projected financial performance on the basis of its environmental risk score. (See Exhibit 5.)

With regard to opportunity identification, there is huge potential for private sector investment in NbS through ecosystem restoration or green infrastructure development. But the complexity of these projects, their often unclear monetization pathways, and their generally small scale have discouraged many financial institutions from engaging in them. One way to overcome these blockers is to develop aggregation schemes and create tools to price the value created, similarly to the way institutions assess and price the value of tangible goods and services.

Financing projects that reduce nature dependency or mitigate negative impacts on nature is another significant avenue of value creation. For example, to reduce their water consumption, some agricultural businesses will need to upgrade their irrigation systems, invest in graywater capture, and begin testing drought-tolerant seed stocks. Institutions can supply the funding that businesses like these need in order to adapt more quickly. There is a growing menu of instruments to provide such support. Options include everything from green bonds and impact investing to market-based solutions such as equities. To determine which projects and financing options best meet their criteria for risk and return, institutions should follow a methodical approach. (See Exhibit 6.)

Set clear targets (even if doing so is scary). Financial institutions may find it challenging to set nature-related targets, especially in the absence of robust data and consensus metrics. But if they want to achieve real-world impact, they must begin to lay the groundwork. We find it helpful to think about target setting for nature in terms of three progressive stages. The first is to do no harm with respect to current climate transition activities. Targets here may include establishing enhanced due diligence and exclusion policies for areas whose biodiversity value is particularly high. Financial institutions can then move on to the second stage, which is to begin developing targets linked to planned financing activities. This can include setting a timeframe for limiting investments in companies that contribute to deforestation. The third stage involves setting targets to deliver positive nature impacts such as specifying a desired funding amount for innovations that increase or protect biodiversity. Such target setting must be iterative and must consider the level of influence a financial institution has over its portfolio companies. Over time, target setting should be quantified and made as time bound as possible. (See Exhibit 7.)

Financial Institutions Can’t Do It Alone

Financial institutions are no neophytes at catalyzing system-wide action. They’ve played this role in connection with climate change mitigation, and they can do so with nature. But they cannot do it alone. Nature is an ecosystem challenge that requires an ecosystem solution. Coordinated action and collaboration by governments, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and the private sector are essential to delivering real-world impact.

Blended finance is one example. To support nascent and small-scale NbS, government bodies and philanthropic organizations need to partner with financial institutions to provide the guarantees, grants, and other support that are essential to increasing the bankability of nature solutions. Closer collaboration is also crucial in making nature-related investments more economically interesting and in attracting catalytic investments. Partnership with local agencies that NGOs help facilitate could surface NbS innovations that are more cost effective than conventional, nature-depleting solutions.

The public and private sectors also need to come together to create the right infrastructure for nature strategies. This includes making structured and accurate location-specific data more readily available. Supply chain data is especially critical—and this data needs to be deep enough to provide both a macro view and deep-dive examinations of upstream and downstream resource pressures. Similar progress is needed on standardizing target setting and accounting methodologies. Optimally, such efforts would be science based and reflect awareness of the nine planetary boundaries. Finally, industry bodies must advance risk frameworks that can accommodate nature risk assessments and enable more effective portfolio steering over time.

Financial institutions can play a pivotal role in helping to right the balance of nature, protect critical resources, restore biodiversity, and enable clients and communities worldwide to design and build a more resilient and sustainable future. Their ability to do so will depend on having a clear nature strategy and the active support of critical ecosystem partners. We hope that our recommendations can foster action on this topic, and we look forward to continuing that dialogue in the months to come.

The authors thank Anne Deserable, Edith Martin, Elsa Maurice, Martin Schnack, Daniel Lohner, and Olivia Shipton, whose insights contributed greatly to the development of this article.