The semiconductor industry is living a paradox. On the one hand, continuous advances in chip capabilities are propelling the global effort to reduce carbon emissions through electrification and energy efficiency improvements in devices and all types of equipment, from appliances to heavy machinery. On the other hand, semiconductor manufacturing causes significant emissions itself, responsible for as much CO2 output as half of US households.

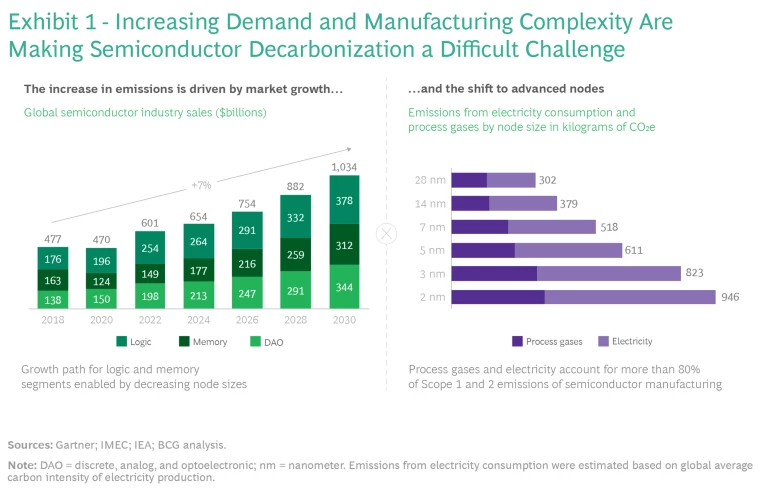

Without immediate action, this situation will likely worsen. Chip makers’ greenhouse gas footprint is expected to widen significantly in the next few years as capacity expands to meet the growth in demand for semiconductors to power energy-efficient devices. Logic and memory chips will be needed in greater amounts, as will discrete, analog, and optoelectronic (DAO) chips. At the same time, production complexity is increasing as innovative advanced nodes, particularly in the logic and memory segments, decrease in size—an improvement that requires more electricity and uses more process gases and other raw materials that further fuel global warming. (See Exhibit 1.)

As these trends play out, semiconductor companies will be under mounting pressure to decarbonize, especially to support limiting the global rise of temperatures to 1.5°C, as stated in the Paris Agreement. Much of the push will come from two sources. First, chip customers—technology companies, device makers, automotive players, and a slew of others in different sectors—are setting ambitious emissions-reduction goals (often spurred by their own customers that favor green products) and are asking their suppliers to help in this effort. Thirty percent of supplier contracts from automotive OEMs already include CO2 footprint limits, and that is expected to reach as much as 80% by 2030. Second, regulatory guardrails, such as the European Union’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive and the proposed US Securities and Exchange Commission rules, are designed to force companies to be more transparent and accurate about their emissions records across their supply chain as the first step for developing mitigation plans.

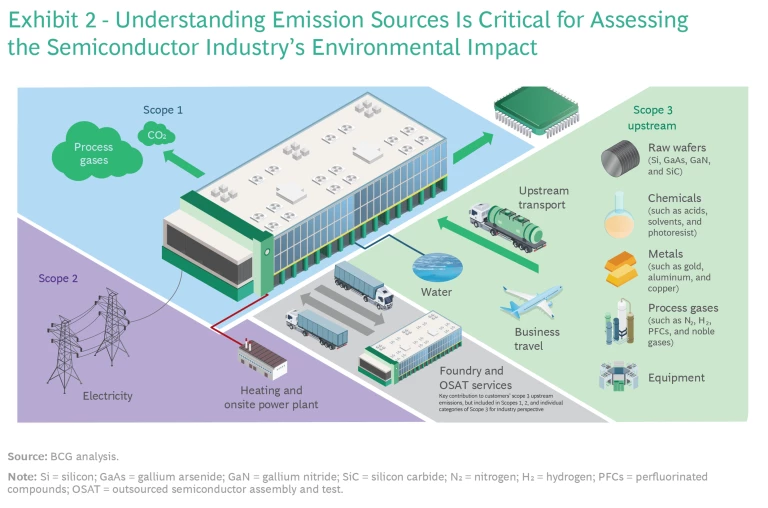

Faced with these pressure points, and in an effort to improve their environmental performance, semiconductor companies have begun to measure and take steps to minimize Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions—essentially, emissions that are directly caused by their own operations and the energy consumed during that operation. But to accelerate their carbon reduction, chip companies must also target emissions from upstream Scope 3 activities. These primarily encompass CO2 output contributed by suppliers; in other words, raw materials, manufacturing, logistics , and the like related to supplier production. (See Exhibit 2.) Upstream Scope 3 comprises about 40% of chip makers’ carbon emissions today (excluding Scope 3 downstream emissions, which cover the actual use of a chip by customers over its lifetime).

With several new fabrication plants already announced and an upsurge in activity at existing fabs, chip makers face a window of opportunity to tackle this significant source of their total emissions at the supplier level. But to do so will require negotiations that are much more complicated than merely agreeing on new contracts and setting up new supply chains . Emission sources in the upstream supply chain are distributed across numerous companies and materials and multiple regions with different manufacturing cultures. Decarbonizing this vast network will necessitate a fundamental change in supplier management. Chip companies will have to work much closer with their suppliers, monitoring and sharing decarbonization strategies with them. Chip makers will also have to rethink value chains to place a premium on curbing Scope 3 emissions.

A Data-Driven Approach to Supply Chain Emissions

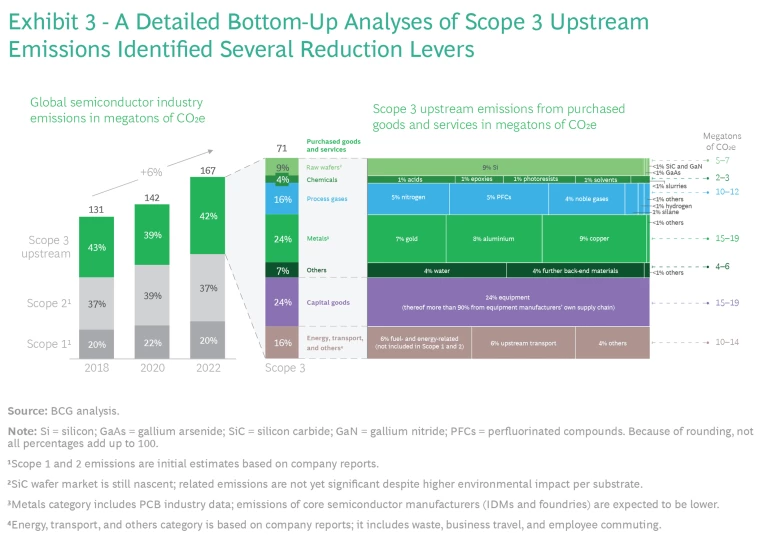

Altering their relationships with suppliers in such new and radical ways will not be an easy task for chip makers. Currently, even baselining suppliers’ actual emissions is a challenge for many manufacturers, often because suppliers do not have a sufficient understanding of the key elements that impact emissions from the exotic, high-purity raw materials used in the semiconductor industry. To help overcome this lack of transparency, we compiled a comprehensive database of raw material consumption and material-specific carbon emission factors. (See Exhibit 3.) Given this, we calculated industry-wide upstream Scope 3 emissions. (Note that downstream Scope 3 emissions, covering the use of the final product over its lifetime as well as its end-of-life disposal or recycling, are outside of this article’s scope, as they require very different approaches for both measurement and abatement.)

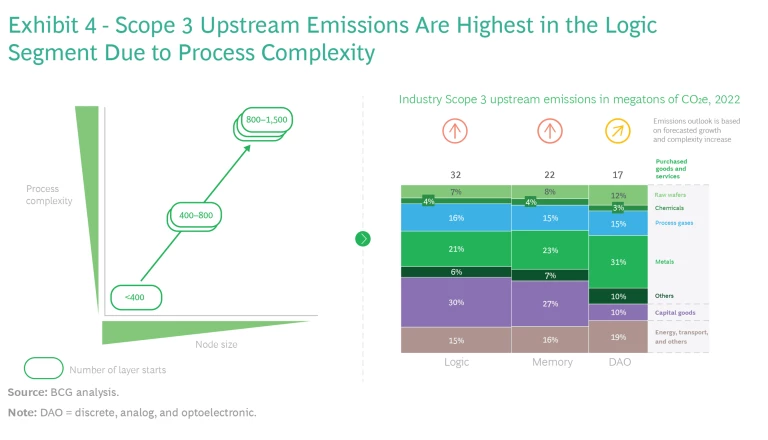

Purchased goods and services are by far the largest contributor of Scope 3 upstream emissions, accounting for approximately 60% of the total. Raw wafers, process gases, and metals are the worst offenders in this category:

- Raw wafer production-related emissions are driven mostly by silicon because it is used in higher volumes than compound semiconductors. Nevertheless, during the production of one kilogram of compound semiconductors, such as gallium nitride or silicon carbide, more CO2 is typically emitted than for the same amount of silicon. This is largely due to the fact that compound semiconductors have higher melting temperatures, and hence, consume more energy during raw wafer production.

- Emissions from process gas production and transport primarily come from nitrogen and argon but also from perfluorocarbons (PFCs), which are a group of highly potent greenhouse gases. PFC leakages that are well below 1% during production and transport can already generate significant climate impact.

- Metals-related CO2 emissions are the result of emissions-heavy production processes (including mining and multiple remelting steps to reach the required purity) and the transport of these high-density materials. Since it is difficult to separate metals consumption in chip making from metals used in other electronics sectors, such as printed circuit board manufacturing, the emissions estimates from this category potentially overestimate the actual semiconductor contribution.

Significant water consumption by chip makers, especially of ultrapure water, contributes about 4% of Scope 3 upstream emissions. Moreover, it can be deleterious to the environment and to communities by contributing to water shortages, particularly in times of drought and in areas where water is scarce.

Other chemicals such as acids, photoresists, and solvents were found to have only limited Scope 3 upstream emissions associated with them, because they are used in lower volumes and more efficiently than process gases.

From the point of view of an individual semiconductor manufacturer, emissions associated with manufacturing service providers, such as foundries and outsourced semiconductor assembly and test (OSAT) vendors, can contribute as much as 20% to 40% to upstream Scope 3 emissions. However, as foundries and OSATs are themselves semiconductor companies and the industry emissions baseline presented here is based on total industry raw material consumption, we do not list foundries and OSATs as a separate Scope 3 upstream category. Rather, we include their raw material consumption in the overall baseline.

In the category of capital goods, front-end and back-end manufacturing tools and equipment are estimated to contribute another 20% to 30% to Scope 3 upstream emissions, according to reports from equipment manufacturers. Notably, emissions are driven almost entirely by the equipment manufacturers’ own supply chains. Emissions from fab and clean room construction projects are not included in this analysis, because their overall carbon impact is low due to their long life cycle of up to 50 years.

We estimated the remaining Scope 3 categories using company reports that pointed to fuel- and energy-related emissions, as well as to upstream transport, as further significant contributions.

A Logical Problem

Examining which types of chips have the most adverse impact on the environment during the production stage, logic and memory chips stand out. (See Exhibit 4.) The number of process steps to produce these chips in state-of-the-art node sizes (less than five nanometers) is three times that of mature nodes. Each additional process step involves more photolithography, process gases, and energy, thereby increasing CO2 emissions across Scopes 1, 2, and 3 upstream. Further, advanced node manufacturing requires a greater number of state-of-the-art wafer fab equipment, expanding the environmental footprint even more.

Pathways to Decarbonization

Driven by the complexity of emission sources, decarbonizing the supply chain requires a holistic transformation. Even though transparency is still a major challenge today, it is just the starting point of this transformation. Sustainability will inevitably become a key factor in sourcing decisions, and supplier relationships will be marked by deep collaboration to reduce emissions.

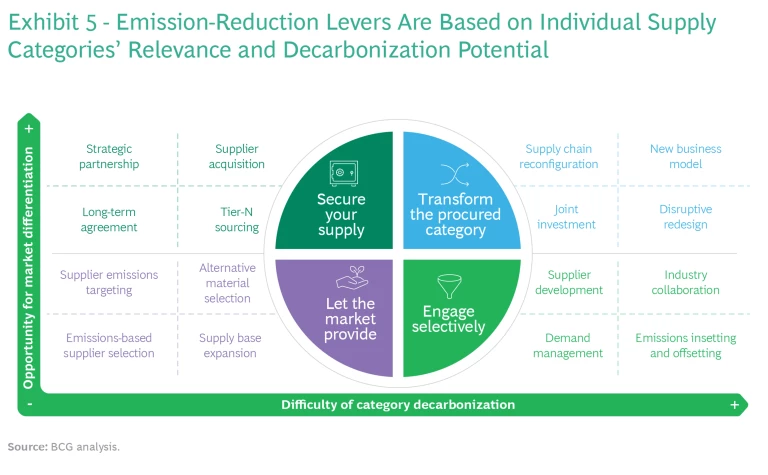

Semiconductor companies will have to pick from a variety of levers to create a holistic program for reducing Scope 3 upstream emissions, depending on the level of their CO2 reduction efforts and the criticality of the respective procurement category. (See Exhibit 5.) These levers can be divided into four groups:

- Transform the procured category. For critical materials with significant CO2 output and challenging decarbonization paths, investing in innovative solutions is required and can be the key to securing a competitive edge. For instance, a semiconductor firm could join with wafer fab equipment manufacturers to develop and implement advanced lithography machines, such as direct self-assembly lithography, which can improve process efficiency, reduce resource consumption, and potentially decrease the number of process steps required in manufacturing. Moreover, they could work with foundries to design new methods for doping (adding impurities), such as plasma doping or monolayer doping, which can help reduce the use of chemicals and process steps while maintaining or improving the performance of semiconductors.

- Engage selectively. For categories that have challenging decarbonization paths but that are not mission critical (such as dielectrics that are used for, among other things, insulation in integrated circuits), collaborating with other chip makers and managing demand, suppliers, and emissions are the right approaches. This way, costly redundant development efforts are limited, while carbon emissions for low-priority but high-carbon upstream Scope 3 materials are addressed and reduced. For example, a chip maker could join an industry consortium forged to develop and adopt low-emission alternatives to fluorinated gases (for example, nitrogen trifluoride and sulfur hexafluoride) used in plasma etching and chamber cleaning processes.

- Let the market provide. In categories that have ready decarbonization paths but that are not mission critical (including basic metals or solvents), focus on selecting suppliers that are using alternative lower-emission materials and that are prioritizing decarbonization whenever possible. A chip maker could set a goal of using low-carbon aluminum or copper for interconnects and wiring and then find suppliers that are committed to using these raw materials and renewable energy in their production processes. Alternatively, a chip maker could prioritize suppliers that are developing bio-based cleaning agents that are safer to use than traditionally used chemicals and solvents.

- Secure your supply. For high-impact categories with relatively easy decarbonization paths, concentrate on strategic partnerships and long-term agreements. A chip maker could form strategic partnerships with suppliers to jointly develop and implement circular economy strategies, such as recycling and reusing metals, chemicals, packaging materials, and even crucial compounds (including silicon carbide). This would reduce waste and the associated emissions in the supply chain, while ensuring that chip makers have sufficient supply.

Tech + Us: Monthly insights for harnessing the full potential of AI and tech.

Taking Action

There are other steps that semiconductor companies can take. They may be slower to produce results, but in the long run, they will have a wide-ranging impact on carbon emissions. For instance, chip makers could create a joint database with players across the semiconductor value chain to develop standards for calculating and tracking upstream Scope 3 emissions and abatement curves. Or companies could form partnerships with chemicals suppliers to investigate whether green alternatives to hazardous chemicals can be produced cost-effectively and perform on the same levels as traditional production approaches. Oftentimes, this will require the transformation of supplier relationships to long-term partnerships that encompass activities and engagements across several steps in the design and manufacturing process. And new breakthrough technologies, such as artificial intelligence (AI), will presumably propel progress in monitoring, predicting, and reducing carbon emissions .

It puts a lot on semiconductor companies’ plates to proactively address a set of issues that are seemingly outside of their control. But as calls for decarbonization in the chip industry get louder and more persistent—and as the chip industry’s record reveals intractable concerns upstream—chip makers cannot afford to view their supply chains’ emissions as someone else’s problem. Now is the time for leading companies to act, secure their own green supply, and strongly differentiate themselves in the eyes of customers, , shareholders, and suppliers.