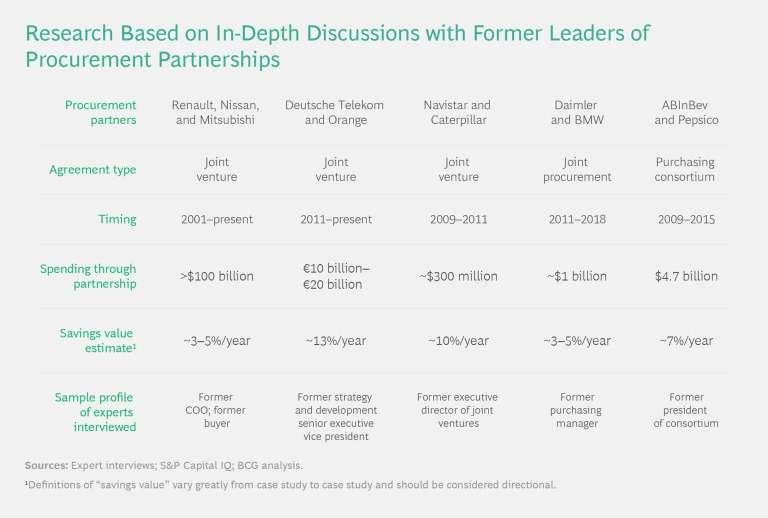

As companies seek improved efficiencies and greater resilience to counter rising inflation and global supply chain risks, many are becoming interested in procurement partnerships. Such partnerships face long odds of success, however. BCG looked at five large procurement partnerships created by global Fortune 500 companies, as well as drawing on our experience in related work with clients, to understand what it takes to make them succeed. Of the five partnerships we examined, two took three years or longer to generate meaningful savings, and only two remain in existence today. (See the sidebar.)

Overview of Procurement Partnerships

Despite the challenges, the payoff can be significant. Successful procurement partnerships can deliver cost savings of 3% to 10% or more of in-scope spending, due to increased purchasing power, economies of scale, shared best practices, supply chain synergies, and the ability to standardize components.

This study focuses on procurement partnerships formed between large organizations. These differ in magnitude and complexity from buying clubs designed to bundle spending among small and medium-size companies or public sector agencies. We look at the difficulties inherent in setting up and managing procurement partnerships and discuss the actions companies can take to help them succeed. Using examples from BCG research and our work over the years in setting up procurement partnerships, we outline recommended steps for companies that wish to establish a successful procurement partnership.

Partnership Benefits

Companies with global supply chains have been working to improve their resilience in the face of new risks stemming from growing geopolitical tensions and supply chain disruptions. The higher costs of some resiliency measures—such as keeping more inventory—are heightening the imperative to find savings to offset those costs.

In a well-run procurement partnership, the partnering companies can share procurement best practices and buy the same parts or components, enabling them to increase their purchasing scale and lower their costs. Partnerships can also help diversify the supply base and improve strategic flexibility, and they can give companies the opportunity to share risky and costly strategic investments in suppliers. For example, partnering auto companies could pool resources to invest in a supplier of battery materials.

One of the most successful procurement partnerships is BuyIn, the worldwide biggest procurement alliance in telecommunications. Founded in 2011 and jointly owned by Orange and Deutsche Telekom, BuyIn has grown to cover $20 billion in spending on network technology, mobile devices, digital home products, service platforms, and information technology. In addition to achieving overall savings of more than 10%—although the numbers differ across domains—the partnership enabled the companies to roll out new joint standards to suppliers more quickly.

Why Procurement Partnerships Fail

Procurement partnerships carry various risks and can take years to deliver measurable benefits, owing to sourcing cycles and the time it takes to establish common designs. They can fail for a multitude of reasons, including misaligned objectives, incompatible cultures, and insufficient resources or planning. Partnerships can also go off course as a result of lack of trust between partners, which is understandable when the partners compete in the same sector. Complex interdependencies with product development, engineering, and manufacturing require careful management to avoid problems. In addition, each partner brings its own existing procurement processes into the partnership, and aligning these for maximum advantage can be challenging. Partnerships can also raise regulatory concerns, depending on the parties’ industry and markets.

How to Build a Successful Procurement Partnership

Although there is no single recipe for making a procurement partnership work, successful ventures tend to share seven best practices, as detailed below.

Choose the right partner. It is essential to work with a partner that is broadly aligned in terms of strategic objectives, sense of urgency, commitment, and company culture (or, if the cultures differ, a willingness to adapt to a third culture for purposes of the procurement partnership). A mismatch on any of these points can be fatal to a partnership.

Both of the partnerships we examined that still exist—BuyIn and the Renault Nissan Purchasing Organization (RNPO)— began with well-selected partners. BuyIn’s owners, Deutsche Telekom and Orange, operated in the same industry and region but were not direct competitors, and they had already formed another joint venture, called EE, in the UK. For their part, before forming RNPO, Renault and Nissan engaged in significant equity cross-investment. As a result, both companies had a similar level of ambition and a strong interest in making the procurement partnership work.

Although these examples may be seen as special cases that cannot easily be replicated, they point to a common lesson: each company considering a procurement partnership should recognize its unique advantages and abilities to work well with potential partner companies based on their shared circumstances.

In a less successful example, two American heavy equipment manufacturers entered into a procurement partnership only to find that they had different strategic objectives in product development, which undermined the partnership within two years.

Define the right scope. The scope of the partnership should be carefully gauged across key spending areas, such as direct or indirect materials, product categories, and geographies. Leaders must consider such strategic criteria as strategic importance, partner overlap, desired impact, time to impact, and feasibility of sourcing supplies through the partnership. Not surprisingly, partnerships work better when they do not focus on proprietary or highly competitive parts. BuyIn, the telecoms partnership, had the advantage emphasizing indirect parts, such as networking equipment—where design is generally less critical to competitive advantage—rather than direct materials for engineering-intensive products, such as cars or trucks.

Develop a strong business case. Companies should develop a strong, unbiased business case comparing the realistic, anticipated benefits of a proposed partnership to the next-best alternative—which typically would be to make internal improvements using equivalent budget and resources. They should base the benefit assessment on external benchmarks and an analysis of representative procurement spending across partners, identifying specific opportunities and including a breakdown of savings by product category, savings lever, and time required to implement the changes. The assessment itself should outline expected costs and the potential introduction of new complexities, with a reasonable expectation that savings will offset the additional burdens. It is important to have a strong business case on paper, but it is even more critical to ensure that all parties involved in the partnership believe in the benefits and have a path to realistically achieve that outcome. To be successful, companies embarking on a procurement partnership should treat the initiative as a strategic investment, not as a small side-project, and should support it with the funding, dedicated resources, and attention it deserves.

A strong business case must reflect realistic timing expectations. RNPO found that standardizing product designs—an important lever that drove most of the cost reduction as the partnership matured—was a high-value objective but required alignment of the product development and procurement processes and design and engineering standards, which took several years.

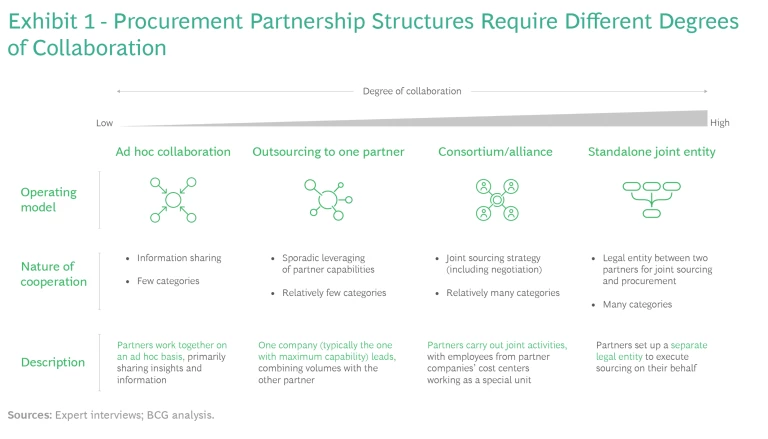

Pick the right partnership model. Joint procurement can follow any of four archetypical structures: a purely contractual collaboration; outsourcing to one partner; a formal procurement consortium; or a procurement joint venture—a new legal entity that provides procurement services to and acts as an agent for its parent companies. (See Exhibit 1.)

In deciding which partnership model to select, companies should consider such factors as the scope of partnership activities, the number of product categories to be covered, legal implications related to competition and the time required to implement the structure.

ABInBev and Pepsico, two global food manufacturing and consumer goods companies, opted for a consortium structure for joint sourcing. Even though choosing this archetype meant accepting certain limits on information sharing compared to a joint venture, in accordance with anti-collusion rules, the structure was faster to set up than a joint venture would have been.

The procurement partnership that existed from 2011 to 2018 between Daimler and BMW involved collaborating on a contractual basis to limit the risk of running afoul of antitrust rules. (The partnership ultimately failed, but for reasons unrelated to the partnership model.)

BuyIn was eventually structured as a full joint venture because the partnering firms wanted to use it to purchase high volumes of goods, and they wanted to act as a single entity to gain greater purchasing leverage.

Obtain committed support from senior leadership across functions. Partnerships stand the best chance of success when they have the support of senior leadership and when participants are motivated to understand and work collaboratively with the counterparty. Visible senior-level engagement is important to embed a sense of urgency and importance in the effort. Partnership management should be assigned at a high level and not delegated.

For example, BuyIn’s success in its early days was due in large part to supportive and adaptable leaders who took the time to learn about the other party’s culture. Leaders demonstrated their commitment and helped build momentum and promote collaboration by frequently highlighting examples of savings successes. The arrangement also benefitted from the strong rapport that individual executive sponsors at the parent companies developed, enabling them to resolve disagreements quickly and amicably. This leadership support and approach should exist across all key functions involved (engineering, procurement, finance, and so on) and should not be just a shared vision among senior leaders. A lack of leadership support or an alignment gap in any one function can stall the effort, even if top leaders are aligned and want to pursue a partnership.

The collaborative leadership that prevailed at BuyIn also enabled the partnership to establish clear processes and roles with detailed descriptions, which in turn boosted the procurement teams’ confidence. One notable example of this cooperative spirit—a step that promoted a sense of fairness and helped build goodwill between the parties—was a one-time payment arrangement designed to compensate for inequalities. Under this arrangement, if one party had a lower contract price going into the joint venture, it would be reimbursed a share of the savings that accrued to the other party as a result.

Prepare thoroughly and proceed in stages. Establishing a procurement partnership is a multifaceted project, and a phased setup process has the strongest chance of success. Key setup phases are strategic alignment, design and planning, integration preparation, and implementation. It is important to involve key functions early, define partnership processes, and align on decision rights throughout the design of procurement processes. Even after they are in place, procurement partnerships have a significant learning curve and take time to bear fruit. Leaders must adopt a long-term view and not expect results overnight.

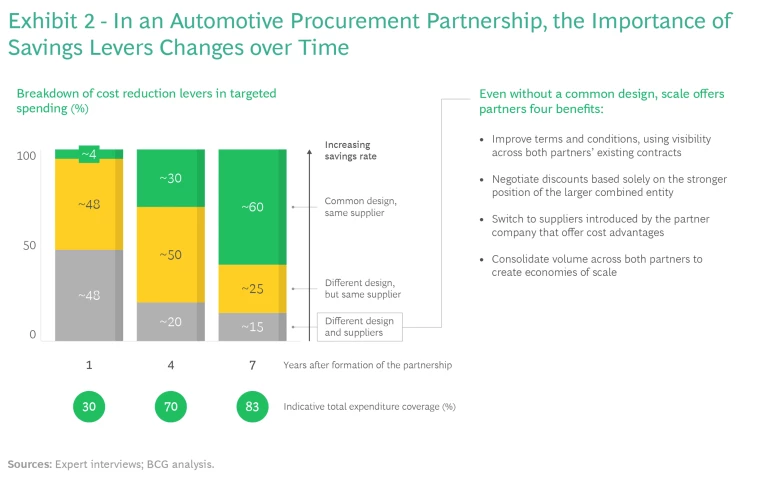

Implementation in stages is important for three reasons. First, such implementation will help control risks—for example, from operational interruptions caused by untested procurement processes in the partnership. Second, it will build support in the partnering organizations by demonstrating early savings before the partnership expands to more complex supplies. Third, it will accommodate the evolution of cost reduction levers over time.

In the first stage, which typically lasts 6 to 18 months, the partners should focus on avoiding operational disruptions and securing quick wins by improving terms and conditions through new visibility across partners’ existing procurement contracts. In the second stage, covering the next 12 to 24 months, the partnership should aim to expand the scope of spending it covers and deliver benefits of scale while efforts to standardize on common parts and materials begin. In the third stage, the partnership should focus on increasing the share of common parts and materials, which will drive most of the savings.

During setup, BuyIn established a documented procurement process, which gave both partner organizations the confidence that they were prepared to move forward, which proved to be an important asset at the outset of the initiative. The partnership then established a very deliberate, phased approach to implementation, starting with networking equipment for mobile and fixed lines and expanding further after each success. This approach enabled BuyIn to demonstrate impact quickly, building positive momentum and overcoming pockets of initial skepticism within the partnering companies.

For RNPO, ramping up to cover the parent companies’ entire procurement scope took 8 years, and reaching the point where full synergies were realized took 13 years. The partnership first focused on comparatively easy commodity savings opportunities, such as subcomponents for common parts like window glass, which allowed benefits to accumulate as the scope expanded to encompass more processes and geographic regions.

The initial savings arose from applying the partnership’s economic leverage to achieve cost reductions for unshared parts purchased from different suppliers. (See Exhibit 2.) As the organizations learned to use the same parts and part designs, and as they identified more opportunities to do so, they consolidated both component designs and suppliers, thereby achieving greater cost synergies and greater coverage of overall procurement expenditures.

Be prepared to transform the remainder of the business. Procurement involves numerous interdependencies with processes such as R&D and product engineering, so it is important to recognize and carry out needed changes in those areas as the partnership identifies synergies. This is particularly important if the partnership includes procuring direct materials: no procurement partnership for direct materials has succeeded without alignment and collaboration on product development and engineering.

For example, RNPO found that it was important to unify the parent companies' development processes and standards before beginning the procurement partnership. Although that approach was time-consuming, it resulted in the adoption of similar engineering processes on both sides. Standardizing designs, which in the automotive industry involves hundreds of thousands of components, helped unlock most of the savings that the partnership achieved after six years.

As higher risks and new costs hit global supply chains, procurement partnerships are receiving renewed interest as a cost-saving strategy. Although procurement partnerships between large organizations—whether in the form of contractual agreements, buyer consortia, or joint ventures—can yield attractive savings for companies willing to take them on, failures have outnumbered successes. Aligning with the right partner and defining the right scope are essential steps, and indirect materials are likely to deliver faster results at lower risk.

To be successful, procurement partnerships also require a tremendous commitment of resources and a high level of senior management attention. Organizations often spend years learning how to make the most of the partnerships they engage in, progressing through numerous developmental stages before reaching a mature partnership that produces attractive benefits. A thorough unbiased assessment and a strong business case are important first steps to setting expectations for the organization. Before establishing a procurement partnership, companies must have a realistic and clear-eyed view of the timing of the opportunity, its chances of success, and the partner organizations’ ability to put the best practices mentioned in this article in place. Without these elements, companies may find that the exciting and sizable benefits that procurement partnerships can bring are just a mirage.